‘My father had seen us wrestle the men, had seen our bodies thrown into the sea of their desires, had seen my mother part the waves: Samira en Moses, minus divine intervention.’

September 29, 2015

When I was eight years old my family and I went on a pilgrimage to Mecca. We took my mother’s car, and completed a journey that many millions of pilgrims have done through the ages, in the desert of Saudi Arabia. This is the story of my small Egyptian nuclear family, visiting for the first time Hijaz.

Listen to the audio version of this story here.

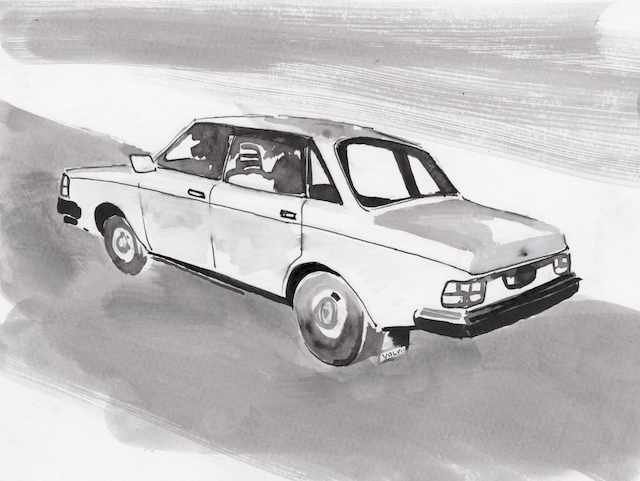

It was rare that we traveled like this, with my father driving my mother’s car. They rode together up front, with my twin brother and me in the backseat of my mother’s sturdy blue Volvo, which they trusted to cross international borders more dependably than my father’s flashier red Chevrolet Impala. We were driving from Kuwait, where my small Egyptian family was living at the time, to Mecca, crossing the border into Saudi Arabia. The trip seemed endless, and perhaps it was, but perhaps it was that I was only a child, and so everything seemed endless. My twin and I were eight years old.

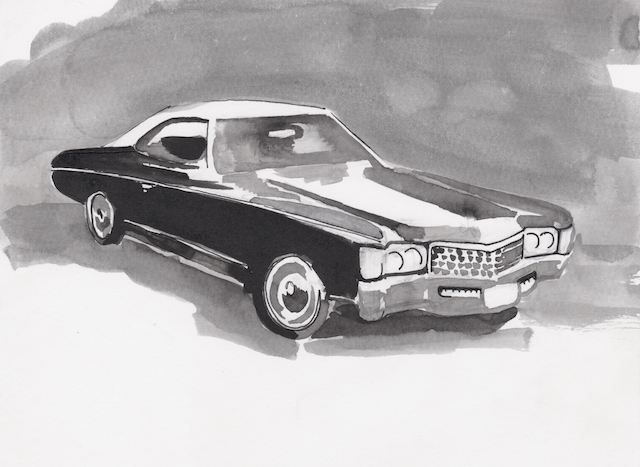

Had it been up to me, we would have taken a chance on the Impala to cover those miles. To me my father’s car was unimpeachable. Not just compared to my mother’s, but compared to every other car in the world. I loved everything about it. It was majestic, the front of it, from windshield to hood ornament, broad and long. The hood ornament—a leaping, angularly-rendered impala—was made of polished chrome, and shone brightly under the relentless Kuwaiti sun. It would not survive my childhood, pried off in the darkness of some night by a thief who would never know that its sudden absence, discovered in the morning of a school day like any other, was my childhood’s first heartbreak.

Looked at sideways, the back of the Impala was shorter than its front, reminiscent of those old cartoons where the front of a car passes and several frames later the cab part finally comes into view. Somehow the shape of it made the driver look as if he were lounging back, in a posture borrowed from race-car drivers, from cowboy Marlboro Men stallion riders, from men receiving skilled, enthusiastic head. It had fins attached to the back, which sliced through the air, making one think of sleek animals of the water, undeterred by its currents. Not only that—the car had survived the Gulf War, the nine-month duration of which my father had stayed in Kuwait for, while we’d escaped to Cairo with my mother. The Impala had come away from wartime with only a single, round, clean, and perfectly circular bullet hole in the trunk. I never heard the full story of that bullet hole from my father, but I supplied into my thirsty and unscrupulous imagination a tale of my own composition wherein my father had proven himself a war hero, barely scraping by death from a war in a country that did not even belong to us: Bond, Ahmed Bond. My father is still the only Egyptian medical internist to have ever saved the entire country of Kuwait from Iraqi aggression, simply by being there.

Impala, I would learn only later in life, is a species of gazelle, and it was that spirit animal that was meant to inhabit the gas-guzzling pile of metal my father drove around, the same car that refused to start three days out of every week. None of that mattered to my young self; back then, my love was blind, and could not see that in truth the car was old, past its prime, its red not scarlet, but rust colored. My parents, living less fully in imaginary worlds of their own creation, understood that my father’s car could not be counted on for a trip of this length, and so had decided that it was not my father’s iron gazelle that would convey us to Mecca, but my mother’s staid, most-definitely-not-red, boxy blue Volvo.

My mother’s car was graceless, though it took us loyally to school on the days my father’s car wouldn’t start. My mother would lean into the ignition, and if the car turned we would sit for many minutes as the engine warmed, my mother whispering to God and the angels whatever allotment of Qur’anic verses she judged sufficient to get us through the car ride safely and without accident or incident. Sometimes my twin brother and I would join her if we knew the simpler verses, but most often we would wait, impatient, while she wrapped her talisman of protection around our little family, my mother an old mother, having had us at forty-two, after a life that had already exhausted her. I resented her car, for the prayers it took to start, for those many minutes of Qur’an every single time we stepped into it, for its lack of majesty, and because it had no fins so that I could pretend that the air was water, and I, a submarined mammal swimming through it.

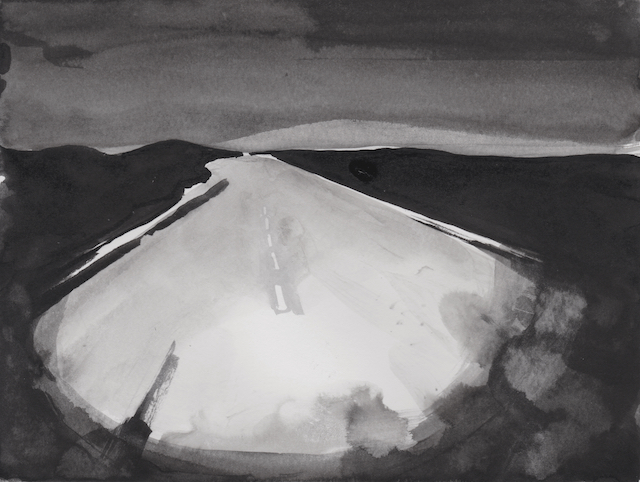

I don’t remember very much about the landscape we covered during the six-hour drive. The desert of Saudi Arabia to my eyes seemed cut from the same cloth as the desert of Kuwait. My parents had decided that an overnight trip would take less time and afford us many more opportunities to disregard the speed limit, and so I think of the first stretch of that pilgrimage as taking place in darkness, with only the white-light headlamps of cars around us breaking up the featureless surroundings. My father spun all the stories he was so good at spinning from the driver’s seat. My mother had made us sandwiches of whole-wheat pita bread with Kiri cheese, our favorite. We washed her sandwiches down with chocolate milk, and though we loved Kiri sandwiches under normal circumstances, there was the slight sour taste of disappointment in them, that our daily fare was so unchanged, even as we embarked on a journey that was supposed to be our rebirth. The cheese came in pleasingly uniform, sharp-edged, foil-wrapped squares, which were neatly lined up in a cardboard box with a tray that slid out. Years later, I would find out that this wonderfully geometric snack was not in fact served in this form worldwide, after I had come to America and tried my first bite of cream cheese on toast.

In addition to her role as sandwich-maker, it was my mother who took me to pee when I needed to by the side of the road. She’d stand in between me and the traffic on the highway, holding a piece of cloth over my modesty, and I would do my valiant best not to pee all over my shoes.

The division between my parents was clear. It was my father who took care of our souls, who told us folk tales from the Egypt of long ago, and the epics of Abu Zeid El Hilali and his clan, from which we borrowed our morality; my father who taught us the stories of all the prophets and how their faith had guided them to surviving danger, to the miraculous, to al-siraat al-mostaqeem, the straight path; my father who knew the words to poetry of resistance and who taught them to us; my father who knew where in the desert to go to climb into an abandoned tank. It was my father who took us on adventures of the mind and adventures of the body, my mother who made sure our clothes were clean at the beginning of them. I had accepted that division of labor as I had all of my parents’ talk of the “natural order of things,” as I had accepted that Eve had come from the rib of Adam, though I’d always secretly wondered why an all-powerful God would want his ostensible masterpiece of creation walking around missing a piece. What was so wrong with clay? Why couldn’t Eve be made of it too?

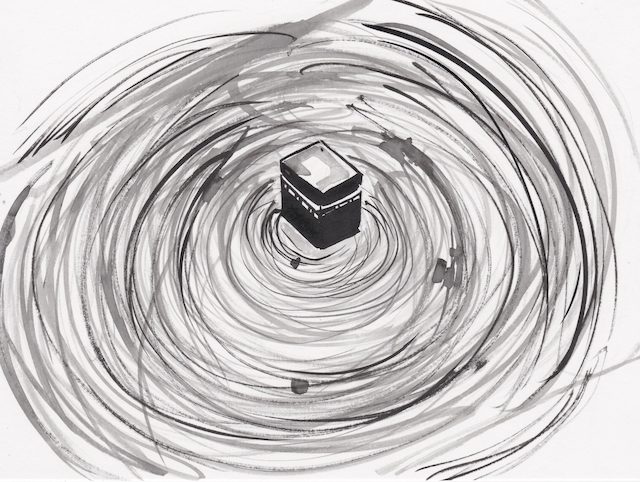

When my father’s voice was raw from storytelling, we chanted, as a family, the labbayk prayer, as Muslims worldwide do en route to Mecca to perform the pilgrimage. We voiced it repetitively in the car, and I would feel the sway and the promise of the words in my bones. I had never spoken to God so frankly before, but here I was, raising my voice over my twin’s to show Allah how eagerly I could serve him. Even to my ears today, there is something of the spirit of Sufi devotional poetry to this prayer, written to the Divine in the language of love. I imagine that moment so many years later, and think of how many cars on that road and how many people in them could have also been driving to Mecca, how many voices there might have been raised, each unknowing of the other, in this chorus, how many of us sang to Allah over the distance of those miles, to say, to reassure, as if to a lover, labbayka allahoma labbayk. labbayka la shareeka laka labbayk. innal 7amda, wanne3mata, laka wal molk. la shareek lak. “I obey. I come, I come. There is no other but You. I come.”

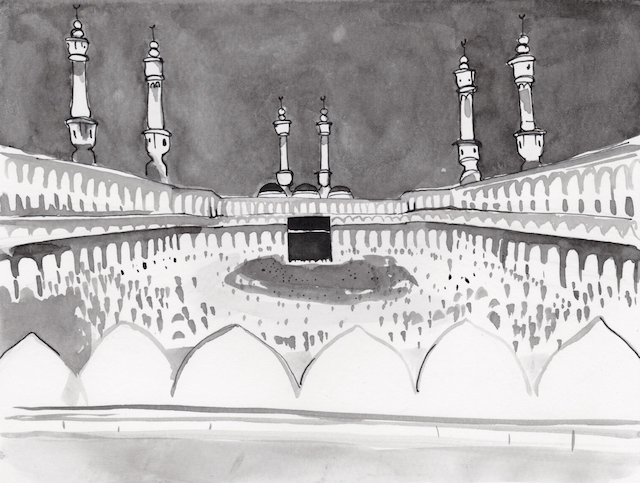

My daily diet of lots of TV had well prepared me for what the holy mosque would look like. Back then, every televised call to prayer sounded over spooled footage of the holy mosque, the Kaaba its central focal point. But nothing could have prepared me for the scale of it all; it was as if giants had built the city. When I entered the holy mosque at one end of the gates, I could not see to the other side of the courtyard for the length of it. There were very tall, white, brightly-lit minarets everywhere, to which enormous speakers were attached, from which issued the calls to prayer throughout the day, the sound echoing off the expanse of ground in the open-air mosque below. The floors were made entirely of white marble, and spaced out throughout the structure were enormous domes topped with golden crescents, the domes themselves intricately inscribed with geometric Islamic designs in the shade of green associated with the prophet Muhammed. Even so, the crush of other bodies was everywhere, pursuing the various rites of pilgrimage, and it was hard to see from their bodies the full extent of this, the holiest site of Islam.

The pilgrimage itself involved a lot of walking. Walking between the Safa and the Marwa, us pilgrims pantomiming the steps of a desperate mother from long ago, searching for water in a desert dry as bone, but for the will of God. The story goes like this: Hajar, abandoned by Ibrahim in the desert with her infant child (also by the will of God), leaves her infant in the sand to run frantically seven times between the two hills, the Safa and the Marwa, and climbs each seven times, using their elevation as a vantage point to see farther, hoping to sight water for her son, Ismail. Baby Ismail, wailing in thirst and left in barren desert sand, strikes an ankle upon the dry earth, and from that spot God saw fit that water should spring, and that the spring be called Zamzam. There were taps everywhere where pilgrims could quench their thirst with Zamzam, this well water believed by many millions of Muslims around the world to have holy and healing properties. Every single one of our relatives had asked us to bring them back a bottle.

My parents took us to the source excitedly, turning on the taps and holding their palms below them, motioning for us to drink the Zamzam from the well of their cupped hands, not wanting us to touch the taps that millions of other pilgrims used daily, many of them putting their mouths directly on the spout. I found Zamzam too sweet, and the experience of water with a distinct flavor strange and unpleasant, though I was too scared to admit it even to myself about this holiest of elixirs. I remember we took a large jug of it back with us, which gathered dust for many months, stored in the kitchen on top of the fridge, to be used for emergencies. We would finally break the green plastic seal a year later, filling tall glasses for my father to drink, after his cancer had been discovered, after his eyes had yellowed, after the chemo had failed.

The pilgrimage was hard on short little legs. It was the longest I’d ever walked. First walking between the Safa and the Marwa seven times, then around the Kaaba seven times, which proved to be even bigger than it looked on TV. On screen it looked dwarfed by the masses around it; in reality not even our teeming numbers could make it any less formidable.

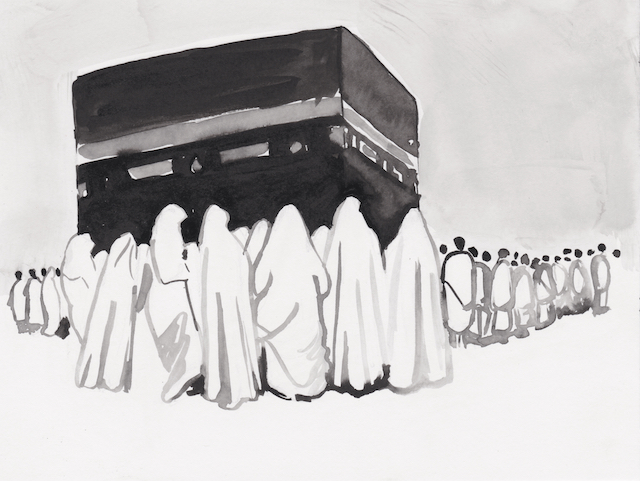

The women among the worshippers circled the Kaaba from a larger circumference, staying farther away from it to avoid the impropriety of touching men. In Saudi, it seemed consistently left to women to prevent any potential impropriety, by denying themselves access. Access to cars, access to bicycles, access to the night breeze on their hair, access to tan lines across their shoulders, access to pants. Because you couldn’t go into the holy mosque with your two legs separated and shaped and defined by that fabric, for all of those fevered eyes to see, to travel upwards from your two feet to your two ankles to your two knees to your two thighs to where your legs are joined back together into the one of you, where they meet. The men also wore no pants, though their dress was made of white pieces of cotton, unwoven, unstitched, wrapped loosely around their bodies, so their bodies could breathe. For women’s bodies, breathing was optional; an activity to be indulged in only when it caused no trouble or inconvenience to others. Polyester would do just fine, just fine.

And so too, to the Kaaba, were women denied access. The Kaaba, which they had just driven a whole bunch of uncomfortable, hot miles to see, peeing on the side of the road. They are denied by the simple ubiquity of the men surrounding the structure: sharks circling, making the waters unsafe.

My dad asked that my mom and I stay on the outskirts of the roving inner circle of worshipers, all of whom were men. He and my twin brother joined that inner circle, though they made no move to get any closer to the stampede around the black rock, my father perhaps feeling protective of my twin brother. It is well known that many get trampled to death in these pilgrimages; they call them martyrs of the Hajj. As I grew older I would hear of more and more martyrs, martyrdom seeming a thing more easily come by than one would expect. Allah did not allow for random acts of disease, of pestilence, of geopolitical unrest, of inattention. And so there were cancer martyrs. War martyrs. Texting-while-driving martyrs.

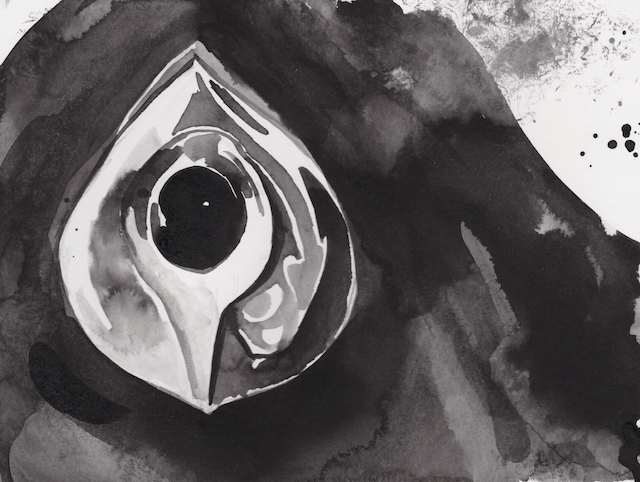

My mom looked at me on our seventh and final revolution around the Kaaba, our final rite for the day. She asked if I wanted to touch the black rock at its corner. The meteorite was encased in shiny metal, wrapped around the small piece of space rock. The story goes that the prophet had lifted it with his galabeyya into place, hundreds and hundreds of years ago, dozens of hands holding the fabric alongside him, bringing together a tribe in conflict. I assessed the froth of activity around the black rock, thinking how cool it would be to tell everyone at school that I had touched it. How cool it would be, how cool I would be.

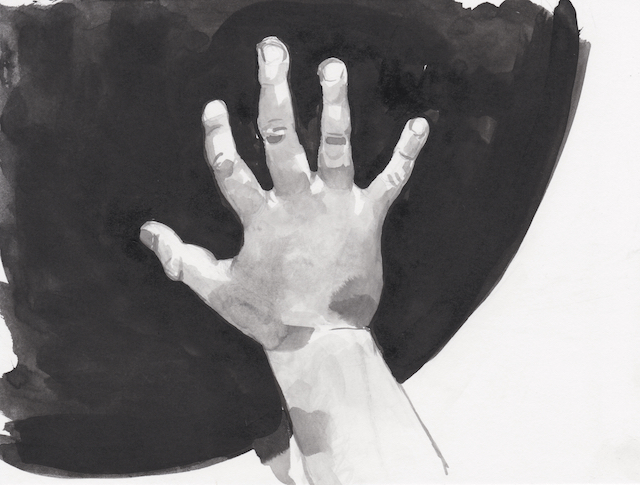

I nodded to my mother. Without another word, she fought her way in through the crowds, jostling the men around us, her soft body normally unused to such rough treatment. I worried that we would get separated—there were so many strangers around us, and I was so small that I could not see the sky from their bodies. I worried that the hand clasping my own would slip, but my mother’s grip was sure. She lifted me up into the air, and with one hand I grasped the black silk fabric of the Kaaba’s covering, studded with kilogram upon kilogram of real gold thread. The covering, made anew annually, had been manufactured in Egypt until 1927, my father had explained to us, his chest puffy with the pride of country that only diaspora can breed. At the time, none of us had reason to suspect that it would be a mere two years until my father and Egypt would be forever reunited, my mother flying solo in coach, my father shipped back like so much luggage, his body cocooned in long white strips of unstitched fabric in the carriage of the plane, a chrysalis from which nothing at all would emerge.

I reached out and touched the black rock, inhaling sharply at first contact, expectant. And then: disappointed. Disappointed that I hadn’t been electrified with holiness, with actual electricity, with the spirit of Allah entering through my tiny finger, with the weight of history, with something. The black rock was cool, even though it had been under the hot Saudi sun all day, a million sweaty palms leaving their salt behind on it, wet mouths touching their lips to it, trying to imprint onto it their devotion. My mother, seeing my little palm make contact, stayed rooted to her spot for three herculean seconds, her two legs turned into one oak, while I soaked up the holy.

labbayk. labbayk. labbayk.

She moved away with me still lifted in her arms, her hands under my armpits, so that I was not in the middle of the crowd as before, but rather afloat above it and its noise. She swiveled away from the Kaaba, wrestled her way back toward the less turbulent waters at the edge of that sea. It was then I saw my father, no longer circling, standing still and facing us, staring at my mother, my brother’s hand held too tightly in his.

My father had seen us wrestle the men, had seen our bodies thrown into the sea of their desires, had seen my mother part the waves: Samira en Moses, minus divine intervention.

Samira: dry as sand, cool as the black rock. Less wet, less salt-smeared, more holy. My father had green eyes that sparkled when he was angry, and at that moment as they looked at my mother they were a terrible, glittering emerald. We did not often witness my parents in conflict with each other, but this silence of his among the din of that place was long and it was still and it was filled with a thousand sharp things. He was angry at her, angry at her legs and her breasts and her almond eyes and her thighs and her elbows against the current of that enraptured jostling. She: she had a secret glint in her eye, something that looked like triumph.

I looked at my twin brother, standing at my father’s side. Big-eyed and newly bald, my twin had gotten shorn along with the other men after the Safa and the Marwa, as had my father, both of them now looking somehow reduced. Their bald heads seemed unnaturally large, the newly exposed scalp pale and vulnerable like a baby’s. I showed my twin the hand that had touched the rock. He reached out to me with a finger, made contact with my palm, outstretched as if with the generosity of the saints, trying to soak up my holy.

My twin and I knew not to interfere when adults talked to one another, and so we stood with heads lowered in silent solidarity while my father vented his rage at her, his voice an angry whisper, my father a man who did not yell. I felt suddenly so far away from this hissing man, a small crack forming in the ground between my feet and his, widening into a growing chasm. Though we stood only an arm’s length away from each other, he felt suddenly unknown and unknowable to me. Here he stood in the middle of Mecca, a man made of clay, and had freely chosen not to approach the holiest relic of Islam. Here he stood in the middle of Mecca, in judgement of my mother and me, women made of the crooked ribs of men, told not to approach the holiest relic of Islam. How could my father, the adventurer, be angry? How did he not understand our wanting?

The next day was our last in Mecca, and we went back to the holy mosque to do our farewell prayers before piling back into the car to drive across the border. I had been told that, this mosque being the holiest open-air place in the whole entire universe, the birds and other small animals that passed through there knew, just knew, even with their dumb animal brains, not to defile it. That Allah watched over it with his all-seeing eyes, a divine custodian. I was told that dust would not gather on its tiles, that sweat would not transfer, that the sun would cool its rays before they reached the ground of that place. That this was a world untouched and untouchable by the filth of our everyday.

A bird flying overhead shat on one of the marble tiles, an ugly brown-and-green streak. I cringed, waiting for Allah to strike me, because I had seen, had borne unwilling witness: his holy house desecrated.

But I survived; Samira was with me. I took my mother’s hand, and I played the game I always played when we walked alongside one another, matching my stride to hers. We left the holy mosque behind, and went out into the world.