The Australian comedian chats about Iggy Azalea, why he doesn’t write jokes for white people, and the power of post-9/11 comedy.

April 13, 2015

Aamer Rahman is quite possibly the only comedian who has the chutzpah to kick off his set with a joke about Israel as a terrorist state.

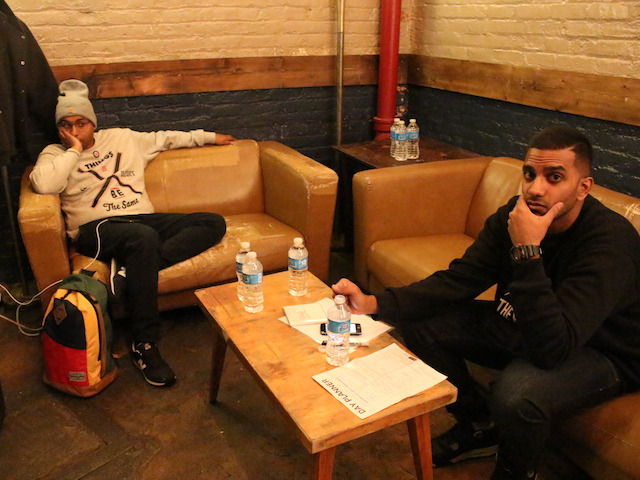

But if the raucous crowd that packed Brooklyn’s Bell House last month to see him on stage is any indication, there’s a receptive and growing audience for the Bangladeshi Australian comic’s blistering, razor sharp takes on topics ranging from Islamophobia to ISIS to Alanis Morissette’s arcane lyrics (spoiler alert: he’s figured out the meaning of the line “It’s like 10,000 spoons when all you need is a knife.”)

Aamer—who’s been described by fellow comedian Hari Kondabolu as “the only person that makes me look subtle”—is best known for his viral comedy routine that skewers the idea of reverse racism.

But it’s clear that Aamer has more to say than just one expertly crafted take down— and in a post-9/11 world, he’s perfected the art of mining the absurdities and indignities of being brown and Muslim for rich comedic fodder.

On tour in the United States for the next two months, he sat down with me before his sold-out show and riffed on everything from Iggy Azalea to why he refuses to do accents to his deep appreciation for his growing fan base, who are, as he put it, the “people who are doing the real work.”

“I don’t write for white people. White people can come, but it’s for people of color,” Aamer explained about his comedy, adding, “Art gives people momentary relief so people can keep surviving.”

BONUS: Watch two clips from Aamer Rahman’s show at the Bell House in March.

Esther Wang: You’ve said before that without 9/11, you wouldn’t have become a comedian. What did you mean by that?

Aamer Rahman: I started doing comedy by accident. And I just saw how much it meant to people to see someone express their view. It was 2006, five years into the War on Terror. I didn’t plan to fill a niche or to give voice to these kind of sentiments, but when we [“Fear of a Brown Planet,” his duo with Nazeem Hussain] started performing I realized that as a community we’re so used to just surviving and adjusting to the fact that we’re not going to be heard. That when we turn on the TV, there’s not going to be someone representing you. So it becomes so normal. I didn’t really consider the ramification of what I was doing until I saw the reactions. That’s always been what drives me.

Is there a certain kind of political work that only comedy can do? I’m thinking of Jon Stewart, and how post-9/11 he used comedy to point out the absurdity of everything that was happening.

Comedy allows for shortcuts. If I have to write a piece about race for some organization or publication, I can’t just be full of rage and emotion, because people won’t take it seriously. But if I get on stage, as a comedian, you’re allowed to speak emotionally. If I make a statement like, “It’s hard for people of color to get jobs,” I can just say that. When I write it, I have to be like, “Studies have shown statistically over time, there’s been a distinct pattern blah blah blah.”

It allows you to cut to the core of how you’re feeling and how people are feeling.

That’s what I love so much about your “Reverse Racism” video. It reminds me of this Louis CK joke about how it’s great to be white and how he could time travel to any period in history, and his life would still be amazing. You’re doing the flip of that. What inspired the joke?

Everyone who has experienced racism knows deep down that there’s no such thing as the opposite. When I got teased at school, my parents would be like, “Well you just say something back.” I can’t say something back. It won’t hurt them the same way.

And that’s why a lot of my comedy is comebacks I didn’t have at the time. I had an argument at school and then five years later, “That’s what I should have said.”

Sometimes it takes me a long time to write because all the stuff I write about are real things that I see or experience. That’s my process, this crazy thing happened, how do I relay that into a funny story.

A lot of your comedy is about Australia, a country that in the US, we know of only because of Iggy Azalea.

The reason [Iggy Azalea] gets to me so much is that her attitude towards race is so Australian. Absolute denial.

John Oliver did a great piece on racism in Australia. He was like, “I’ve never met people who were so comfortable being casually racist.” When I go to the US or UK, it’s not that they’re not racist, but there’s a level of immediate racism that’s not there. People have learned over time you shouldn’t behave like that. That’s not to say it’s not there. In a day-to-day way, it’s very different.

What I love about your comedy is that you don’t give that “in” for white people to laugh at you, versus with you.

People always ask me if I change my set given the audience. I never ever change my set. Party because I’m not really a guy that can juggle, because there’re comics that can build a set as they do it, I just can’t do that. If I try to do my bits out of order, it just comes apart.

And also, I’d rather me be uncomfortable in a given night where there’s a few too many white people who are not getting it than shuck and jive for the audience’s convenience.

You were an immigrant and refugee rights activist in your previous life. How does that compare to comedy?

I think the artist has the easier job. Not that it’s easy. I’ve been on the other side, and it’s so taxing and so difficult.

That’s who comes to my show, people doing really hard, really committed activist work. They’ll come in after the show and be like, “Hey, really love your comedy.” “Thank you for coming. What do you do?” “Actually, I volunteer at an immigrant rights organization,” and it’s six days a week and deals with all these horrendous issues.

And they’re thanking me. It’s so humbling. I’m like, you should not be thanking me.

I think those people are doing the real work. My job is to, not speak for them, but to keep producing stuff to keep those people going, give those people some room to breathe. Because whenever people are subjected to racism, sexism, homophobia, the first thing they’re told is that it’s not happening.

As an artist, you’ve said before that your biggest influence isn’t other comedians, it’s hip hop. Who are your hip-hop inspirations?

When I was a kid, I would listen to what’s on the radio, which I loved. But when I got a little bit older, that’s when I got into Public Enemy, KRS-One. They’re also from an era where it wasn’t like, “Oh, this is conscious rap.” That was just what hip-hop was doing for a couple years.

It was a huge influence on me. How to be angry and artistic at the same time and it’s not something that needs to be toned down or white-washed. There are other people just as angry as you and they want to hear it that way.

There is no genre or art form that has discussed race as openly and for as long as hip-hop has in a Western setting. There’s nothing. There’s no genre that has discussed social justice with respect to race and policing and criminalization in a way hip-hop has. Hip-hop gets zero credit for that.

If you’re a kid who grows up looking up to Malcolm X, where are you going to find representations of Malcolm X that treat him like a hero, that actually preserve his legacy or the Black Panthers? Or a genre that celebrates Dr. King and Malcolm without pitting them against each other? Hip-hop.

Who do you listen to now?

I love Bam, I love Blue Scholars. Less and less, newish stuff.

Any favorite comedians?

Chappelle. Margaret Cho.

Some of her stuff, I don’t really know.

I started loving her when I was a teenager. Something of hers came on totally by accident. I want to watch Margaret Cho without any white people, because I don’t want white people to laugh at that. I just want us to laugh at that because we lived it.

That moment during the Golden Globes…

I was just, no, no. You’re a prop.

There’s something about skewering your own people that I appreciate, but there’s a line.

That’s why I cannot do accents. I can’t have one white person laugh at that. I just can’t.

WATCH: Aamer Rahman on Iggy Azalea

WATCH: Aamer Rahman on ISIS