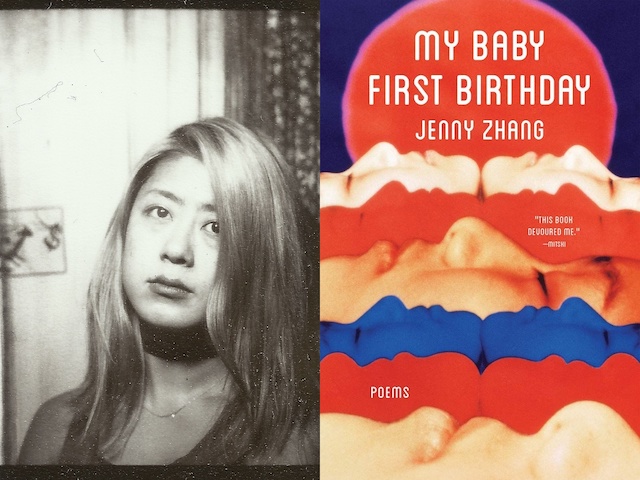

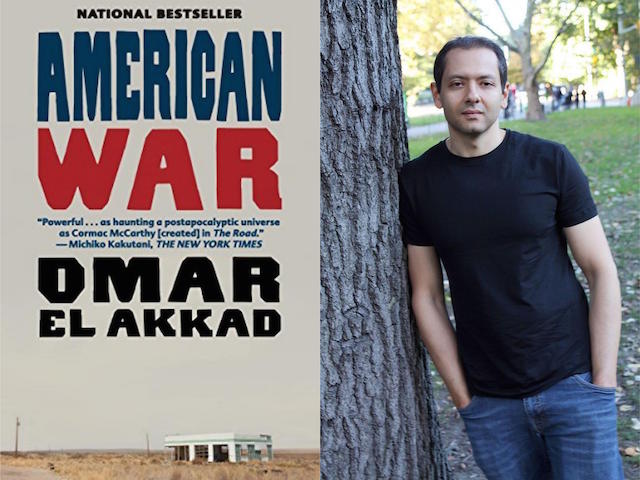

The American War author and journalist talks climate change fiction, writing in the age of Trump, and reinventing America in his novel.

February 28, 2018

In his debut novel American War, Canadian Egyptian writer Omar El Akkad imagines a not-so-distant future in which a second civil war—over a ban of fossil fuels imposed after climate change has led to massive flooding in the Southern states—has divided America into North and South. The war, which is recounted to us in the early 22nd century by one of its survivors, is characterized by drones, torture, refugees, extremism—in short, phenomena that we tend to locate elsewhere. At the center of the narrative is the Chestnut family from Louisiana, and their daughter, Sarat Chestnut. Sarat is six-years-old when the war begins, and adopts increasingly radical ideological beliefs and actions as it progresses.

As our own present-day political reality devolves, this imagined future starts to seem eerily plausible (the narrative also imagines foreign meddling that escalates the conflict in the United States, along with a resurgence of coal mining). As a staff writer for Canada’s Globe and Mail, Akkad’s coverage of events in Afghanistan, Guantánamo, and Ferguson provide an incredibly effective and accurate underpinning and trajectory to the fictional events in this novel. I spoke with El Akkad about translating reality into fiction, “dystopian” narratives, and localizing the “exotic.”

—Zaina Arafat

Zaina Arafat: You spent ten years writing for The Globe and Mail. How did your experiences as a journalist inform this novel, or shape some of the decisions that you made in terms of writing it in a future time period versus the present moment, or even the past?

Omar El Akkad: As a journalist, I covered everything from the technology industry to the Arab Spring. A lot of brown people are familiar with the phenomenon of being the only brown person in the room when a story involving other brown people comes up. You start getting dispatched because you’re the only person who knows something about Islam, or who spent time in the Middle East, or who speaks Arabic. So the experiences that ended up informing the book include my experiences covering the war in Afghanistan and military trials in Guantánamo Bay. The scenery in Camp Patient is based on a lot of what I saw in those places. But I did a great deal of research to enhance the “interrogation” (or whatever euphemism for “torture” they’re using these days). And that obviously played a role in the construction of some of the chapters. On a thematic level, there was an element of symmetry. I went to an Arab Spring protest in Cairo, and I went to a Black Lives Matter protest in Ferguson, and while those two events are informed by vastly different histories, events and ideologies, the tear gas was the same.

We’re experiencing a massive refugee crisis that we tend to associate with far off places, particularly places in the Middle East. How did you decide to bring these things here to the United States, especially the refugee crisis, along with the idea of young people getting radicalized?

I had just moved to the U.S., but if you grow up in the Middle East, half of the things you see on TV are American. The music is American. The highest volume of stuff in your life is American. But this is not a book about America, and I have to make the case that even though the book is called American War, it’s about the universality of revenge and the idea that anybody subjected to enough injustice and violence can become unjust and violent themselves. At the same time it was necessary to set the book in America, albeit in an invented one. Growing up in the Middle East, or growing up in a certain skin color, ethnicity, or religion, you become used to the idea that if somebody is going to represent someone who looks like you, they’re either going to be the “Good Muslim,” the “Bad Muslim,” or the “Fruit Vendor Whose Fruit Stall Gets Destroyed In a Car Chase.” But it rarely happens the other way around. [In the book] coasts are gone due to climate change and there are drones in the sky. It was interesting to turn the table that way and see what kind of story would come about from taking these things that are applied in one direction, and applying them in the other.

I haven’t seen that done so skillfully and in such a subtle and clever way. And in terms of the threat, it’s interesting that the instigator of much conflict was climate change and environmental concerns.

I have no doubt that in the next few decades, there will be some very vicious conflicts predicated on climate change and immigration. Places like Bangladesh, which is probably the most susceptible native country to rise in fossil fuels, also has some of the poorest human beings on the planet. Those people are going to have to move in some cases, and that’s going to come with immense conflict. I was thinking about the idea that many years from now, when it’s safe to do so, people will be able to say “well, that was terrible, I can’t believe they didn’t realize it.” The thing that’s causing this is also the duel for one of the biggest commercial empires on the planet, and something that makes our lives much easier every single day in a million different ways. I wanted to get at this idea of something that is ruinous right now, but will be very easy to call “ruinous” much later when everyone is aware of it. That’s how I got into climate change and fossil fuels as the cause of the conflict.

What is the goal when you’re writing a dystopian novel? Is it meant to be a thought experiment? Is it meant as a cautionary tale? Is it meant to offer a different way of looking at our world now?

The word “dystopia” never really crossed my mind until the first reviews started coming back from booksellers and from other publishers who bought the rights in other countries. For me, the idea of the dystopic has to do with extrapolation. And you extrapolate the folly and the flaw of the current age to show that it could happen. Certainly there’s an element of that in my book. There’s nothing in this book that hasn’t happened in one form or another. It can happen to somebody far away, but the book is almost entirely a work of creative theft. The massacred camp patients are not something I sat down and invented from scratch. These are deliberately gross interpretations of things that actually happened. When I think of why I started writing this book, a number of reasons come to mind: the first, and probably most superficial, was that I was angry. I was angry at the idea that it’s so simple to live in this privileged part of the world, and then imagine people on the other side who don’t have the privilege of living in peace as being somehow exotic, or as reacting to these events in these ways that we never would. The other reason I started writing is because I had been thinking about what we should do about this terrible thing that’s happening in that part of the world. It actually boiled down to pretending that the victims look and sound like you.

I imagine that when you started writing the novel there was no sign of Trump on the horizon.

No, no, I finished two or three weeks before he announced he was running for president.

Do you think the fact that things seem even worse here now than we could have even imagined changes the way you would’ve written this novel, or your view on these issues? Does the political landscape at this moment cause you to view the project any differently, even after having written it?

It certainly influences the questions and doesn’t really influence the answers. I got a lot of questions when I was on my book tour about Trump-this, or this administration-that, or whatever. But this book outlives me, and it outlives its age, and one day, if I’m fortunate enough that people are still reading it a week on past whatever this miserable situation that we’re in right now, it will be read in a different context. And I look forward to seeing how it gets judged on those merits. I suppose that if I get mentioned in the same sentence as Margaret Atwood, besides being incredibly flattering, it helps sell a couple of copies, then it helps make it easier for my publisher to frame the book in the sales pitch. In the long run, my hope is that it’s not the kind of book that needs a situation as insane as this to stand on.

I found the protagonist, Sarat, to be very well developed, and I wondered what your experience of creating her character was like. It’s not always easy for men to write women well.

The options for me and the options for a writer with fairly limited talent is to write what you know in terms of character development. And my only sort of ironclad experience in terms of character development is with a 35-year-old Egyptian-born, Middle Eastern-raised, Canadian man living in the U.S. And that guy’s really boring, and no novel in the world could stand on that sort of character. My other option is to venture into places that are outside my experience and risk doing it badly or risk doing it wrong. I don’t know if I succeeded in creating a believable or even a good character, so my only hope is that I at least went into it with a place of good faith. When I started thinking about this person, I wanted someone who was defiant, and defiantly curious. Someone who wanted to know as much as possible about everything around her. But I also wanted her to be trusting and loving and to believe the things she was told about the world around her. Because the central arc of the book, and the central circle of tragedy of the book, is how that curiosity and that trusting nature is used against her until it’s fully turned on her. And that was the central idea of trying to write this character.

Do you expect readers to like Sarat, or at least sympathize with her?

I get asked that question often. The answer from my perspective is that I don’t want you to sympathize with her. I don’t want you to like her. I just want you to understand how she became the way she is. Much of the book shows how someone can start off as a trusting, curious young girl, and then be manipulated in such a way that by the end of the book she’s fundamentally evil.

What are you working on now?

I’m working on a repurposed fairytale, among other projects. American War came out in the spring of 2017, and then a couple of weeks later, my wife and I had our first child. So everything is caught on the back burner right now.

Congratulations! Though I’ve heard that having a baby can make a writer more productive, believe it or not, so there’s hope for you.