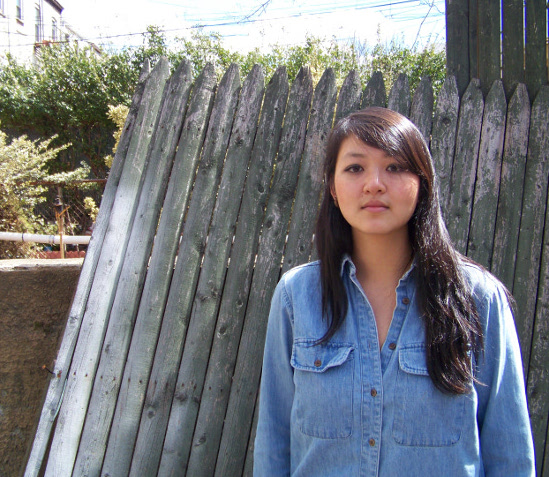

Ashok Kondabolu of Das Racist catches up with documentary photographer Annie Ling at her Brooklyn apartment.

April 23, 2013

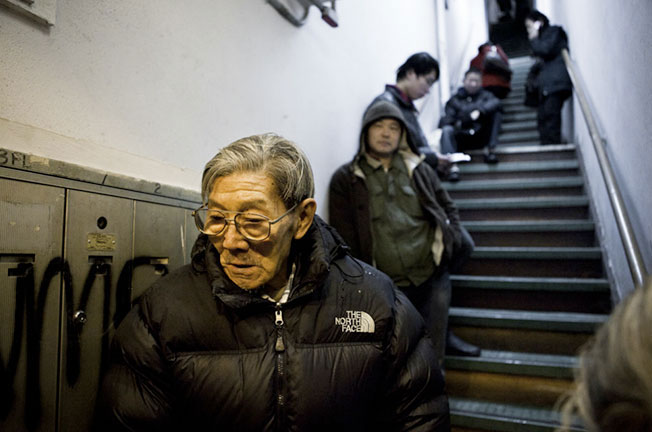

Annie Ling, a Canadian artist and documentary photographer, was born in Taipei and made New York her home more than four years ago when she moved to the city to pursue photography. Much of her recent work is concerned with people and place, and the ways in which we lose and search for community. In 2011, Ling captured in photographs the stories of residents at 81 Bowery, a Single Room Occupancy building in Manhattan’s Chinatown where rooms go from $100 to $250 a month. The tenants, mostly Chinese immigrant workers, had their lives upended when they were pushed out of their homes by the city in 2008. They fought hard to return, only to be faced with another vacate order this past March.

Ling is no stranger to displacement. Four years ago, her apartment in Chinatown was destroyed in a fire that killed two and injured 27 others. “I virtually became homeless,” she says. This March, when the case following the fire closed, Ling looked back on the photos she took the night she lost everything. “As an artist, I always go with what I feel,” Ling explains. “I burned the photos of the buildings to try to show them on fire. To push as far as I can visually to create images that tangibly show how much in danger this community is in. It’s such a precarious situation.”

An exhibit of her work on human trafficking in Eastern Europe opens on April 25 at the All Things Project space in New York City. The Museum of Chinese in America will host a solo exhibition of her work this fall.

Ashok Kondabolu recently caught up with Ling at her Clinton Hill apartment.

So, how did you get started doing photography? This is very obviously a corny question, but…

Oh man. How did I get started? A lot of my colleagues got their start very young, or were influenced by relatives or family. I had nothing like that. I never thought I would do photography.

I took this postcolonial literature class senior year of college and it completely seeded this direction for me. Because that course was all about perspective and how we view the Other and how we create these stereotypes. I realized something I studied—the material and the theories and what we were discussing there—clicked with what I was familiar with growing up. Which was moving all the time. Always getting exposed to different perspectives. And realizing that was something you need to nurture and that’s something you need to express and show.

For me, photography is a way of combining my love for creating visual content and telling stories, and also understanding my perspective—my constantly changing perspective—and how that works with other perspectives and how to look at things from other ways of seeing.

Why did you move here [to New York]?

I moved here to pursue photography. Really it started for me—this desire to do photography—about five years ago. Four or five years ago. I moved here and it was just a steep learning curve from there. I applied to a program at the International Center of Photography and I was really surprised to get in. Applying six months after the deadline was due, I got in and quit my job in two weeks, and basically school started. I was always drawn to New York but I never knew what would draw me there. I always thought it would maybe be drawing, painting, something of that sort.

So I know you were born in Taipei. Is there a significant Taiwanese population in Manhattan’s Chinatown?

I wouldn’t say a significant Taiwanese population. I would say more Chinese and mainland China, but my family in Taiwan, they really came from mainland China. It’s a little bit hard to distinguish. I guess there’s a little bit of a distance with some people that I meet. But most of the time, we get each other.

And probably in New York City, the distinctions mean much less.

I don’t know. Sometimes it has to do with connecting with where you’re from, but I think most of the time here it has to do with an actual physical connection. Like presence. If I’m meeting somebody and we’re from the same area, it doesn’t necessarily mean that we’re going to connect. For example, the people that I photograph and spend time with and build a relationship with… we don’t really have the same story, but we have an understanding of each other simply because of time we spent together and the level of trust and comfort we’ve built.

So I know you lived in a building that caught fire four years ago on James Street, that’s by the F, the East Broadway stop by the water?

I guess it’s called Chatham Square? It’s where a bunch of places meet. East Broadway, Mott Street, my street.

There’s that statue with the benches around it. And that gun store, right? There’s like a gun shop, I think, over there?

Was there? I don’t know. I was mostly just attracted to food vendors while I was there. [laughs]

And your building was completely Chinese? Primarily Chinese?

Mostly, but not all.

Is that the first building you lived in when you came here?

I looked at so many different places when I first came to New York and lo and behold I ended up in Chinatown of all places.

Oh, you had no intention of specifically moving to Chinatown?

No, not really. It wasn’t my prerogative, but I ended up in Chinatown.

You’re going to hear this again and again: I feel like with a lot of things in life, I don’t choose it. It chooses me. Like the work that I do. Even in hindsight, it seems really clear. That chose me. That building, that home. I ended up in that community, I guess, among the Chinese diaspora that I could relate to.

I wasn’t exactly thinking, “Oh, I’m going to move here and start documenting everybody.” My concern was, “Alright, this is gonna be home. I’m going to make it a home.” After four or five months I felt at home. That’s when the fire happened. And I was all of a sudden made homeless, and more than that, I saw all my neighbors and people that were very close to me lose everything.

So there was a fire. And your apartment burned down, I assume.

Yea, it was in the middle of the night. Typical of tenement buildings in Chinatown, there’s no fire alarms, there’s no sprinklers. It basically doesn’t meet a lot of regulations you have in typical buildings, so when we found out, there really wasn’t a moment to grab anything. We were running for our lives.

It’s surreal for me to even describe it. In my imagination, it doesn’t seem real to wake up choking on smoke, crawling out on your fire escape where people who are seniors are rushing up to the roof from the flames, carrying babies up and helping each other jump off to another roof before the windows exploded and everything caved in. It really doesn’t seem real that I lived through this. I was mostly horrified by just how quickly I could be uprooted. And I noticed everybody around me had no idea of what’s next. And everything you lose you can’t be compensated for.

After this happened… It’s a touchy subject for me because I ended up in a Supreme Court case.

Against the landlord?

Well, against the negligence. There was negligence. This fire happened, but the court case only came to a close last week. So it’s been an emotional time. It made me realize that you don’t really get justice legally. Because according to the legal system, you only get what you lost with monetary value. As an artist, I have lost priceless things. They don’t really… care. It doesn’t really have that much of a value in that sense.

So, I guess there’s some parallels to that eviction at 81 Bowery. How long did you spend going to 81 Bowery and talking to people living on the fourth floor?

I think it was a few years ago. When I was there I started by visiting some of the men that really welcomed me. I basically walked in one day and I said, “I’m looking for someone to talk to. I’m a photographer and just would like to get to understand, get to know you guys.”

How was that initially? Cause it’s, like, tenuous legally. Did people react angrily to you being there? Suspiciously?

No, I was trying to be very respectful. If they didn’t want me there I wouldn’t have stayed of course. I had a connection with one of the older ones, and I would end up not taking pictures immediately but going to visit and watching Chinese operas with him. Just spending time.

It’s not that I just wanted photographs. I wanted a relationship with these guys because they reminded me of my father, who I don’t have a relationship with. These guys left their families to be breadwinners and they sacrificed the intimacy of being with family so that they could provide for them. When I heard about these guys, I just knew I had to meet them. Because I never got a chance to see how my father lived.

He worked abroad?

I never saw him. His life is mysterious to me, but yeah he worked abroad a lot.

When I went there, after a while, I explained myself. They understood. Some of the guys told me that I reminded them of their daughters who they hadn’t seen in a dozen years or so. So that’s, I think, an important thing to get across. There was that relationship first.

So the eviction came about because there was like a Poppy Harlow, CNN, semi-sensationalist story about the place. Which is to be expected for mainstream news outlets when they need something like this to spread to the rest of America which doesn’t even understand what it’s like to live in a city. And then someone from Arizona tipped the FDNY and they evicted the residents after that?

It was a vacate order, not an eviction. A lot of people think that this happened because of gentrification, that the landlord wanted them out. But in fact these guys had been evicted by the landlord years before and they were out for a year and they fought their way back and they won the trial.

This is different. This is a vacate order from the city. The city came in and gave them a few hours’ notice. But you know, that didn’t give a lot of time to people to make a backup plan. The doors were all knocked down.

The organization CAAAV [Coalition Against Asian American Violence] has done a tremendous job of advocating for these people, in the past and also now. So they believed that the CNN piece that was done in a very sensationalist way had set off this concern from someone in Arizona that the city doesn’t care about these people, so they have to be rescued. The day they were being vacated I showed up at the end. I showed up as soon as I found out. It turned out CNN was there the same day for a follow-up piece. I’m not sure if you’ve seen it.

No.

I felt very disappointed. It seemed a little naïve because they were asking these people who became dear friends of mine if they were relieved that this happened because they were leaving these unsafe conditions. They’re very aware that this isn’t an ideal way to leave, but they left their families and they have a community there, which is more than a lot of people can say in Chinatown that live isolated in tenement buildings. They’ve built a family for themselves. When this family they’ve built for themselves and this community that they’ve created is lost, they’re very much alone. More alone than they were at the Bowery.

A lot of them have been there with each other for over a dozen years. They support each other and come to each other for any concern. So, I’m disappointed because everyone is in limbo. It just really reminds me again of what happened to the people that lost the building in the fire four years ago. We’re in limbo. At the mercy of time and the city figuring out what to do.

Is there some sort of temporary housing set up?

I believe people can apply for temporary housing if they can get everything together.

But it’s not just a quick fix. Let’s have a bed. Let’s find a new room and a new bed. A home isn’t just a place. A home is where you feel comfortable and you belong. It’s part of your identity and who you are. When you take that away, you do get disoriented. It’s hard to find your way when you get uprooted so suddenly.

Well, we’re in this triangle of those two neighborhoods that I was talking about earlier. So you’ve lived in Manhattan’s Chinatown your entire time in New York City?

After Chinatown, after the fire, I virtually became homeless myself for over a year. I moved—I lost track of the count—at least twenty times in a year. Just anywhere I could sleep to get through school. I was still committed to finishing what I started, but of course I had to take a leave of absence because I had to start from scratch and I didn’t have insurance and it’s very difficult to be here. [laughs]

Yeah. [laughs] Let’s move away from the extreme heaviness. How do photographers generally, or photojournalists, make a living? Is it just pitching assignments to places? Or taking assignments?

I can only speak from personal experience. I know this is not a desirable or lucrative profession. But really for me, I see it less as a career and more as an attitude. Photography brings me joy. It helps me understand—again we go back to perspectives—how to see things from other perspectives. And try to understand how I see the world. It’s very exciting. I think I could go on and on just how being able to see tangibly the way you set a distance between you and a certain subject or you and a person or you and a story—how close or how far you are—it can help you understand a lot about yourself.

It’s not just a tool that I use. Well, I guess, maybe it’s a tool. It teaches me a lot. It constantly teaches me a lot. So, for making a living, I hope that I can make a living doing great assignments and meeting all kinds of great people. But at the end of the day, I have to do what I have to do sometimes. Last year I took a job painting houses when I couldn’t pay my bills.

That actually sounds pretty awesome.

I would be covered in paint and I’d get a call from the New York Times saying like, “We’d like you to go and shoot this.” And I would drop my paintbrush and I would clean up and go and shoot. And this might be the hidden side of what many people see as “glory job.” I do what I do to get by. [laughs] Making the most of what I have.

So, I know you’ve done a lot of what I guess for lack of a better word I’d call social pieces. Pieces with social interest, angles. But you’re also a working photographer. I was looking through your website and you had photos of hip-hop artist El-P, and he’s smoking cigarettes or throwing a ball in the air with sunglasses on.

Tomato.

Is that what that was? I knew he probably didn’t own a red ball. He grows tomatoes?

Yeah.

Wow, he’s never mentioned that. I can’t imagine that man growing tomatoes.

Well, he’s got a sensitive side.

I never see him during the day is what it is. So, how is it, say, working—not that it’s necessarily heavy all the time—but doing those social interest pieces and having to, on the fly, take photos of a man throwing a tomato in the air? Cause it probably elicits different feelings in parts of your brain? Or do you find it’s a continuum?

I’ve been getting more assignments photographing environmental portraits.

An environmental portrait, like a dude hanging out? Is that what it is? [laughs]

Yeah. A portrait of a person in a context. That’s a really rough definition. I mean, for me, a person and a place are very interesting. There’s limitless possibilities, and I think that it would be very tough to be doing what I’m doing if you’re not interested in people. I find it very rewarding to meet these people. Just to have access to so many different kinds of lives and perspectives. It’s incredible to me. I’m always learning and I get to see what it’s like from their side. It’s never dull. For me to photograph, to pursue a personal project that’s lengthy and I get to go as deep as possible and then simultaneously do a portrait for Fader or New York Magazine, it’s all things that feed me as an artist.

I know you took some Sandy photos. Post-Sandy photos. Were you downtown during that period of time?

No, my editor wanted me to photograph Manhattan. But I was stuck in Brooklyn, so as a result a friend of mine and I decided to drive to South Brooklyn or South Queens, I guess. The Rockaways. I’ve always been interested in the Rockaways ever since I shot there a few years ago for a different publication. But I had visited Rockaway Beach and at one point got access to Breezy Point. I wanted to see what they were going through. I was very fortunate living in this triangle that was slightly above everything else. It really was night and day. Some people lost a lot and everything.

My internet went out.

My internet went out too. That was tragic, you know. Awful.

[laughs]

I really felt like I wanted to understand what other people were experiencing at the same time. I went to Breezy Point just after the bridge opened to the Rockaways. The next morning a lot of media arrived, but I was there before all the media arrived. It was really eerie. Everything was under water. And it was dark. I was just amazed by the people who were diligently working day and night to help each other. That’s an incredible thing to witness. How people come together when you see someone in need.

As a photographer, when you see something like that—a disaster or after a natural disaster—there must be so many visually interesting things. But you might want to exercise this restraint because you feel, maybe not exploitative, do you know what I mean? That feeling of wanting to capture everything but also having to hold back?

Yeah. I think you’re touching on a really important thing. I think photography is subjective, of course. But it is also very hard to lie with a photo. When you create a piece of work and you stand in a certain place and click a shutter at a certain time, where you stand is very obvious. If you’re very close to a person, if you’re catching them in a moment of vulnerability in a sensitive way, you have to know why you’re there. And that comes through. Your motivation comes through in the image that you create and put out there.

That’s the part that you have to consider too. What do I want people to think or see when they see this work? And of course, people can think whatever they want. But your job is as a communicator and you have to know what you want to communicate.

If we’re talking about journalism, the deeper you go and the more time you spend with a subject, the more arresting and profound images can be.

Finally, the plugs slash future work portion. What are you working on? What are your plans for the future?

Oh man, so much going on. I’ve created a lot of work, lots of projects and done research in the last couple of years. This year I’m really trying to put it out there.

Last year I spent two months in Eastern Europe with a friend and colleague looking at the problem of human trafficking. That was a very intense experience. It’s taken me a long time to go through that work and to edit. I’ll be showing this work to the public—the work that I created in Eastern Europe about trafficking—which is basically a collaboration with survivors of trafficking to photograph places that enable trafficking and their stories.

In the meantime, I’m also putting together an exhibit at the end of October with the Museum of Chinese in America. It will be the first solo exhibition of all the work I’ve done in Chinatown.

For more on 81 Bowery and Annie Ling’s photos of the building’s residents, check out The Tenement Life in Open City.