Ashok talks to artist Andrew Kuo about the history of painting, making his own Wu-Tang shirts, and Linsanity

January 13, 2017

I don’t remember when I first met artist Andrew Kuo, but I used to see him at the old Max Fish all the time in the late 2000s. A few of the t-shirts he designs and (usually) gives away found their way to me by osmosis. I didn’t know he was a real-deal artist with several big gallery shows under his belt until years later. His approachability and “regular guy” interests (sports, pets, pop culture) threw me off his scent. I caught up with him during the tail-end of his latest show “No To Self” at the Marlborough Chelsea gallery that represents him, in a nice, bright corner room where Kuo said he occasionally watches NBA drafts. Kuo’s show ends on January 14.

Ashok Kondabolu: I’m here with Andrew Kuo in the Marlborough Gallery in Chelsea on 25th Street. When did your show open?

Andrew Kuo: Oh god, was it December 4th, I think?

December 4th, it’s called No to Self. How many shows have you had in your life?

In my life? I’m guessing off the top of head, like, 10 probably.

Damn. I have no gauge if that’s a lot or a little.

I don’t either.

Where did you go to look at art when you were in high school?

This wasn’t really the spot when I was in high school because I was in high school in the 90s. It was a lot of museums and SoHo stuff at the time. I remember right [when] I got out of college in the late 90s, 2000s, it was still going on in SoHo. All of the big galleries here like the Gagosian, Werner, Matthew Marks all had spaces below Houston, which was crazy because the spaces were so different. There were pillars and they’re old now. All of these spaces have been built just for them.

Right. But what do you prefer, if you have a preference?

I don’t, I like the white-wall vibe. You know, I liked the MoMA back when I was a kid. I kind of prefer that over adapting something else to art. It’s like a moving target—it depends on the work that’s hanging and the architecture of the place.

I feel like with your large “chart” painting it would make a lot more sense because if you have that in the wrong space, it’s like, well why is there an old radiator next to this precision graphic?

Last year I had a show at this great gallery called Half Gallery uptown and it’s in this beautiful building with a spiral staircase going up. Each room was really small and there’s a fireplace in every room and the guy there, Bill [Powers], does a great job of like dealing with all of that and making it real nice and putting the proper size painting in the right space and letting the fireplace just be the fireplace.

You grew up in Flushing, is that right?

I was born in Flushing. I grew up in Westchester right above Yonkers in a place called Edgemont.

And you went to high school upstate?

I went to high school at Edgemont High. I always say upstate and then my friends who are actually upstate get mad at me.

How was Edgemont High? I remember when I watched representations of high school on TV with cheerleaders and football players and goths and that kind of hierarchy, I’d be like, “What the fuck?” It’s either like you’re a nerd or you’ve got to go home to your parents or you smoke weed or wait for a bus. Was it more “typical” there?

It’s funny because I feel like my generation was coming off the reverberations of revenge of the nerds and computers, and by that time, in the 90s, the nerds were already rich. IBM was a big company, even movies like Animal House and Police Academy—it was kind of like this nerd bubbling. You know, that whole 80s narrative kind of reverberated towards the 90s where I remember the star football player of my high school liked Nirvana and Stone Temple Pilots and wanted to sing in a band and was mad at his parents for making him play football, which was funny, because for people like me—short, and not white—I was like, “Well then, what do I do?”

It was pre-where people would want to [align] themselves with nerds. The word nerd doesn’t mean anything anymore because everyone is like, “I’m a nerd, I love Batman.” Batman is a giant, multibillion dollar franchise that everyone is familiar with. My mom has just incidentally seen every Christopher Nolan Batman because they’re all on TV. It doesn’t mean anything. I was putting in the work in my parent’s basement being a loser when I was like nine.

I always think about that when my friends say, “You know I just want to date a nerd.” I’m like, “You mean you want a model or a quarterback with glasses who listens to Modest Mouse, right?” I’m like, “Modest Mouse has sold a million records, man. You don’t really want to date a nerd because they’re in their basements and they’re not that nice.”

Did you know, at a young age, that you wanted to be an artist?

It was kind of weird. It was like an inverse bell curve thing because my grandfather was a painter. He’s from Taiwan. And my mother was an art critic for a Taiwanese newspaper.

That just destroyed a lot of my follow-up questions. But how do your parents feel about you being an artist?

It’s more traditional than I would think. I could draw at an early age, and they were like, “You can go be an artist.” But, as most Asians who immigrate to America, it kind of elasticizes back to, “No, you need to be a doctor. No, you need to learn to play violin and be a doctor.” My mom made a deal with me. If I got into a really, really good college—there were like two colleges she wanted me to get into—she would let me go to art school, thinking that I would drop out of art school and just go back to one of these colleges.

Like let him get there on his own.

Right, so I got into that college and I ended up going to art school and I loved it. But painting seemed so ridiculous to me in my teens and early 20s. The Internet was happening, people were making mix tapes, you know.

So painting felt like, what, static?

It felt really old fashioned.. But, then talk about elasticizing, it came back. I just strictly started painting, but it’s informed by printmaking so I don’t have an easel and a palette.

How would you describe your art? To me, it seems like it went from really precise, complicated shape, color, complications, geometrical to more simple, representational stuff. How do you describe your art when you have to write blurbs and shit?

Yeah, definitely! The representational stuff of like flowers or my friends and the words are one side of it. Then the abstraction like the color coding and the shape and the reduction into shapes and solid colors are another end. I kind of compare it to a ping pong match versus yourself. You start really close, right? Then someone hits it hard and you back up. Usually the other player backs up too. Or in this case, the other player backs up, which is myself or the representational side, and then you volley.

It’s almost like a need I have after reducing something to talk about something specific. It’s always a case of magnifying and pulling away. As I get older and the longer I stay on this track, the volleys are getting really tight. A lot of the talking is faster and not as extreme so for this show, I have around a dozen abstractions that are caption and one geometric abstraction that is caption and one painterly abstraction just to diffuse it.

Painterly abstraction?

Yeah because there’s no hard lines, there’s no description of the shape of an area. There’s no mechanical aspect to it, a straight line, a right angle, whatever. But who knows, maybe next time I’ll just want that volley to extend again.

I saw a documentary about this seven-foot-tall Punjabi guy, Satnam Singh Bhamara, who might be the first Indian player in the NBA. It got me mildly excited, even though I don’t watch sports really. What was the feeling of watching Lin during the Linsanity days, as an Asian American and as a Knicks fan?

It was overwhelming, especially with the narrative of the Knicks as being an inept organization. He seemingly appeared out of nowhere, looked nothing like anything we’ve ever seen, and balled out. I felt proud to be Taiwanese American. I felt proud of my heritage before Linsanity, but I was touched by it all. I hope Bhamara makes it.

Why did the Knicks trade him? How has his post-Knicks career turned out? I don’t watch ball enough to know.

They let him leave to join Houston. He signed a contract with the Rockets and the Knicks decided not to match it for a few speculated reasons: the Houston contract was back-heavy and too expensive, Carmelo [Anthony] didn’t like a bigger star on his team, or the world is generally racist and dumb, including the NBA world. I claim a 25/50/25 percent on that.

I just bought my first down jacket. And whenever I bought a North Face down, they never worked out before, I was in layers. But now I’m trying to–

Streamline!

Streamline!

Not as fun, but works better.

Works better. I just don’t care to express myself in that way as much anymore, it just takes too much time. What is your view towards fashion in that way? Has it changed? Do you think about that shit?

I think about it a lot. I’m that cliché and I think a lot of people have been talking about it recently, which annoys me. I wear the same thing everyday.

Literally same shirt, same… colors?

I have backups for everything. I buy packs of t-shirts. I usually get a gray sweatshirt that I order on Amazon and I stack some under my desk. They’re 20 bucks each. The jeans are all Uniqlo. So I have a stack of those under my desk. The socks, it doesn’t matter.

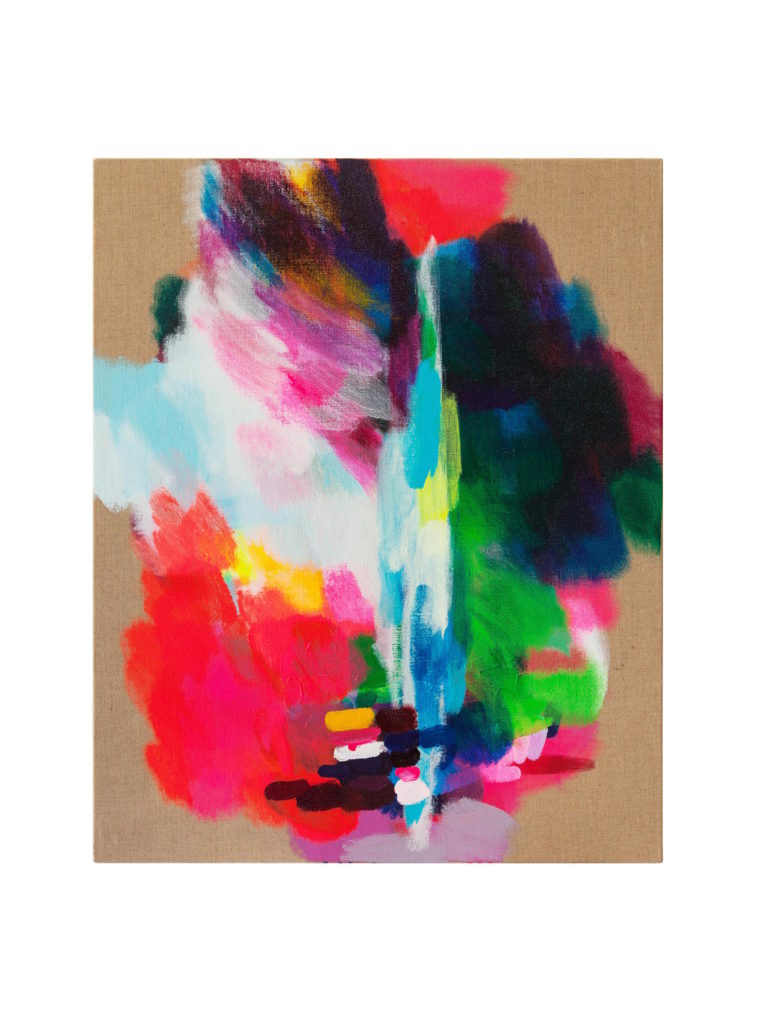

Kuo, Portrait (Nose), 2016, acrylic on linen, 30 x 24 in

Are you a regimented person in general and is that part of your routine or is that just specific to the clothes?

It’s specific to the clothes and I’m pretty regimented. Well, I’m not regimented but it’s sad when I don’t do the things I don’t want to do. It’s like we have dinner plans and I was just hoping to read an article on the Internet and eat some food that I know is in the fridge.

And now you have to reschedule that article.

Yeah, and that’s just sad to me. I’m not malleable. But the clothes, it’s like, I always think I’m being very mellow but actually I’m like hyper, hyper-OCD about it. I have these packs of sweatshirts just wrapped in the plastic, ready to wear. Usually if I run down to two, I’ll order two more just so I know I have them. I heard Clarks were going to start discontinuing the low top suede Wallabees, so I went ahead and bought seven pairs.

When did you start designing t-shirts? What was the first batch?

High school. For real, well in high school, I used to paint my own shirts with a brush. I used to go to shows and whatever band and I was seeing, I used to paint, like Unrest or Unwound, or, whatever, Wu-Tang Clan, you know. In college, I was really into screen printing, so I started doing it then. But it’s super expensive to buy blanks and everyone wants a free shirt. Today before I met you, I sent out a pack of shirts to someone online who wanted some. It’s been constant, I like the idea of giving stuff away, I like jokes, so what better opportunity than t-shirts?

I love to see my friends wearing them. I sold a bunch recently at a book fair and it kind of bums me out to sell them but I had no choice because after giving away a few shirts, it gets really expensive.

And then by selling them, the people that you give them to value them more because that’s how capitalism works. I know your Twitter and Instagram handle is @earlboykins, the short basketball player. Are you afraid Earl Boykins will do something terrible and you will have to uproot your entire Internet persona?

Ohhh. If he does something dastardly?

Exactly.

I never thought about that. Because I just thought he was this great guy, but that’s all right. I would just change it up. I always think, what would happen if he hollers at me and is like, “Can I have my stuff back? My name?”

Right.

The answer is yes! I’m not going to fight you on this. I mean, I check to see if the real Earl Boykins is on. I don’t know if he cares about the Internet.

How do you source the weirdo animal images on your Instagram?

I just search every platform that aggregates anything I search, so I don’t really have one way to do it. I don’t know how to describe its’ sensibility. It’s pretty self-apparent, but to describe it, it would be “nothing mean,” humans doing dumb stuff and maybe animals doing really smart stuff. Or the opposite, I don’t know. Absurdity. Nothing cute.

Do you own a cat or a dog?

I have two cats.

Okay. I wanted to ask because I felt like if you didn’t, it would just be very weird.

Yeah, I’d be that guy, right? I might still be, but yeah.

I’d be like, “This guy’s a phony!”

Your chart-making those were computer-made, right?

Yeah.

Did you ever think in the process of making those, “Why am I going to hand make these larger ones?” Have you ever thought of simplifying the process of it?

Yeah, every day. I mean, the paintings are about paint and they’re about the history of painting as I see it. I think artworks that I really like talk about the history of that artwork, whether it be sculpture, film, music. Even new music is coming from a place of understanding. When you hear something fresh, or even something you like, it doesn’t have to be fresh. t usually talks to some sort of past. It’s like, “Oh man, he’s got a little bit of Elliot Smith in there. It sounds like Detroit house a little bit for a second.” I think a lot of painting has to talk about the past, the history of painting.

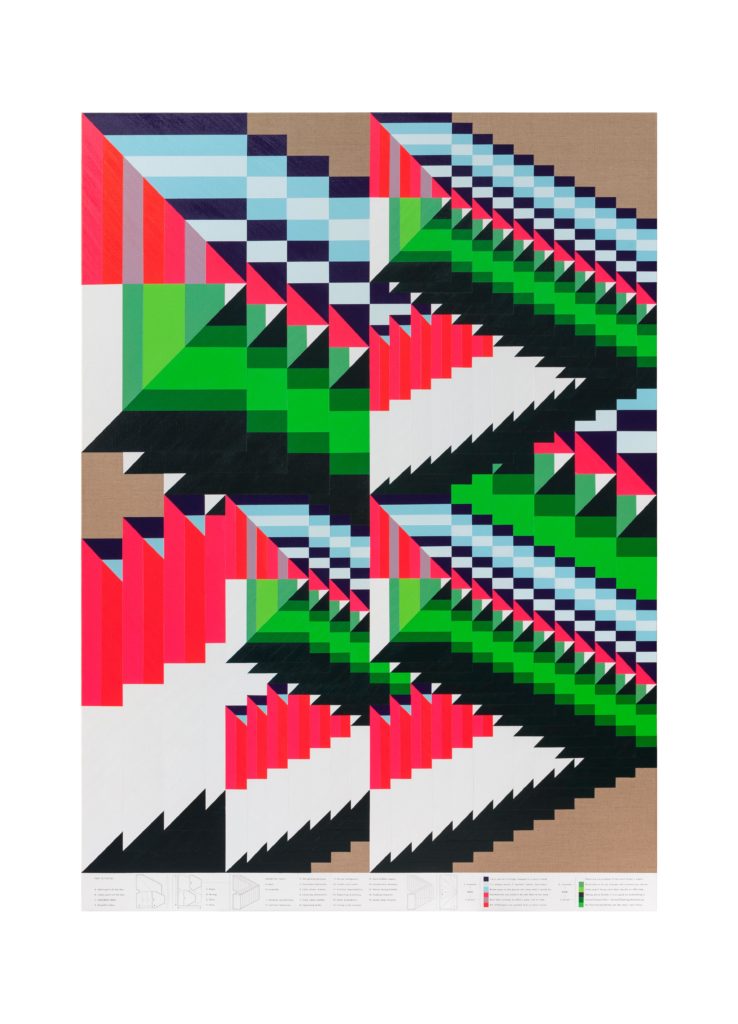

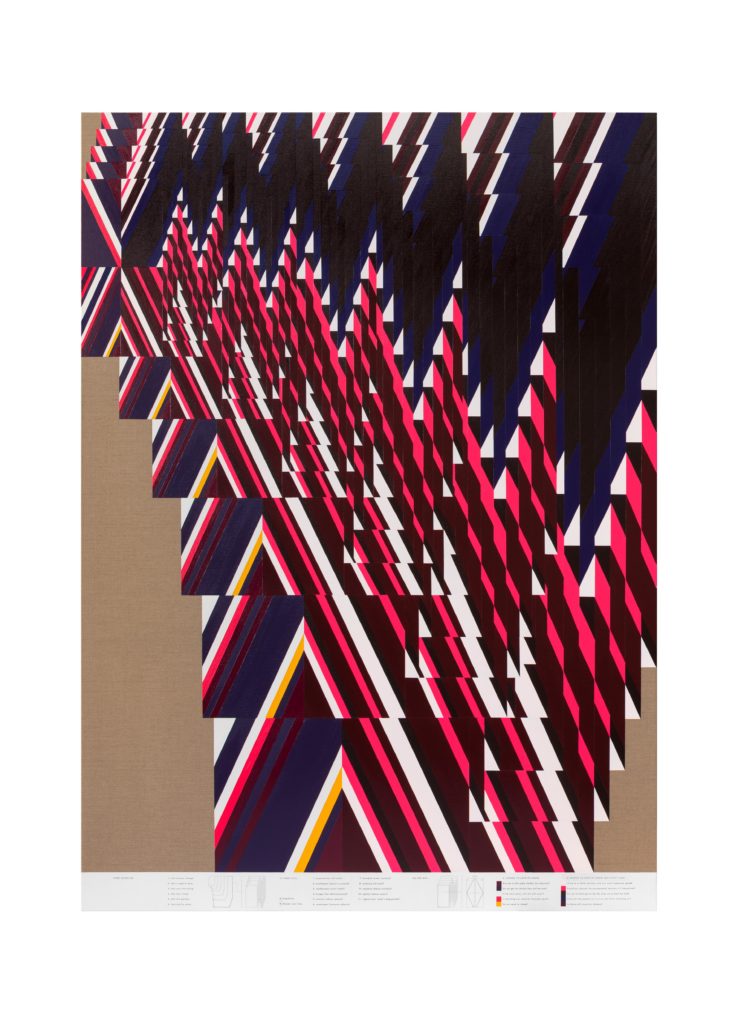

Kuo, FORWARD (9/28/16), 2016, acrylic and carbon transfer on linen, 86 x 62 in.

I feel cultures and generations are cyclical, and each individual essentially is cyclical.

Yeah, and I think it’s valid to talk about why don’t I print out the paintings and just stretch them, right? I think that’s valid to a lot of different discussions that some great artists did. I really love Wade Guyton’s work and that talks about that. Jeff Elrod does a lot of printing and painting. But, for me it was literally about all the paintings are drawn on paper and then I’ll copy the drawing on the computer and then I’ll literally look at the computer screen with a ruler in the program, and with a pencil and t-square mark off everything on the linen, and then paint it by hand afterwards. That’s a really important process because I’m not talking about modernism; I’m talking about something before that—just painting.

The physical process.

Yeah, and these are clean shapes and they’re clean lines but when you go look at them, you can see all the mistakes and you can see the surface quality of the paint and that’s a whole universe. If you just wanted to talk an hour about viscosity and surface quality, I’d love to. It’s something I really focus on.

Right. I guess a lot of it is just how geeked you are on the process.

Yes, and it tells a completely different story. If I walk in with a handpainted Wu-Tang shirt versus a silkscreened Wu-Tang shirt versus a Wu-Tang shirt I bought at a place that I modified, those are three completely different conversations that can be had and are all great. But with these paintings, I gravitate towards the hours it takes to physically put it down slowly and to sit there and wait for each layer to dry and then do another one. You would never ask me how long something takes to make if I printed it out. You’d be like, “Yeah, you just printed it out.” Meanwhile I could have been, “Yo, it took weeks to figure that file out.”

Do you feel like that process is an integral part of your life, that brings you joy? And it just happened to dovetail with this thing called art that you can then present to people?

Definitely, like I love the long processes of things. But, back to the whole tiger mom thing, this may be some sort of self reflective, practicing violin thing. I don’t believe in the ten thousand hours theory at all, I think that’s a wonderful idea and it works for some people, but I definitely commit myself to that. And I’m only at the beginning of that, or maybe I’m at the end. The time is important, and a lot of these paintings talk about time.

Would you ever have a team of assistants making art for you assembly style, like Dale Chihuly?

Dale Chihuly. He does great things with glass that look like sea anemones. He went to RISD, and he actually shows at this gallery uptown. I don’t know. Right now, I don’t want an assistant, and it’s really challenging for me to get work done. Sometimes the paintings can only get so big because I have to carry them by myself.

Can I ask a practical question? Where do you paint? Do you have a giant studio somewhere?

I paint in Bed-Stuy. I have a space, it’s great. I have a freight elevator right outside my door. My guys who fabricates these things for me just brings them right in, but I have to carry them around and it’s precarious. These things take space. I really am appreciative of [that] I can make something and then that thing will live somewhere else and I can make another thing. That’s a privilege.

When I was younger, I had these conceptions of life and art and myself. When I approached creativity, I was like, “Wow, it would be ill if I made one great album that I can hang my hat on or one great movie and then I would be set.” And it’s been kind of like this at every stage of my life. When I was 18, I imagined what 25 was. And if I had these things, like a bar where everyone knew my name, and I could hang out in some shitty apartment, damn, that would be sick. And then when I was 25, I had all of those things, but I was like, “Fuck this.” I realized there is not going to be this point where I’m satisfied, where I’m like, “You know what, I’ve got three good works of art that I stand by, I’m done, I’m off to the woods.” You have to learn how to exist and how to live with your work almost as a byproduct of that balance. What are your goals with that kind of thinking in mind?

What you said is something I think about quite often and I agree with you. There are little milestones. You have little goals for yourself. Maybe a writer wants to write a thousand words a day. Having a gallery that supports me has changed my life and deciding that I wanted to paint instead of make sculptures has changed my life.

Kuo, FORWARD (9/28/16), 2016, acrylic and carbon transfer on linen, 86 x 62 in.

I personally always think about empiricism. I feel like it’s important to be empirical about your life but not in a binary way. It’s not like, “Well, as soon as I make that film, I’ll achieve what I want to achieve.” No, you’re constantly in a beta version of yourself. You’re testing stuff out, but you know empirically what you’re trying to get to. I want to make good films. That’s empirical. What do I think is good? How do I get there? Who’s gonna help me? How much will it cost? How much time will it cost me? What do I have to sacrifice to get this film done? Is it my relationship? Is it my family? Is it my happiness? Is it my sleep?

There are unlimited things I want to do for the rest of how many years I have left. But I know certain things are out of the question and I know certain things are part of the question. I’ll never be a musician, but I’ll play some records back to back. Maybe at a dark, dingy bar, back to back, I’ll play some songs and it’ll be fulfilling I’ll never be like Dr. Dre. That’s off the table. It’s not gonna happen but I could still mess around in Garageband and make a funny beat and be like, “Time to go to sleep,” and it’ll be fun. That’s an empirical kind of thought.