Solving the mystery behind a Chinese Indonesian writer’s forgotten account of the final years of Dutch colonial rule through Indonesia’s armed revolution

April 29, 2016

Historian and political scientist Benedict Anderson (1936-2015), best known for his seminal work on nationalism, Imagined Communities, first traveled to Indonesia in 1961 as a graduate student doing fieldwork. “Indonesia was my first love,” Anderson wrote in his posthumous memoir, A Life Beyond Boundaries, published this month by Verso Books. “I can speak and read Thai and Tagalog, but Indonesian is really my second language, and the only one in which I can also write fluently, and with the greatest pleasure. Sometimes, I still dream in it.”

Benedict Anderson was expelled from Indonesia in 1972 after publishing the “Cornell Paper,” a critical account of the aborted coup on September 30, 1965 that led to the mass killing of 500,000 to one million suspected Communists under the orders of General Suharto, whose 32-year dictatorship of Indonesia ended in 1998. Anderson was allowed back into Indonesia in 1999.

In the following excerpt from his memoir, Anderson recalls first coming across a book published in 1947 about the final years of Dutch colonial rule and the Japanese occupation of Indonesia by a writer who went by the name Tjamboek Berdoeri. The book epitomized a colonial cosmopolitanism of the time that was unlike anything Anderson had read before, but almost no one else had heard of it. He resolved “to solve the mystery of why a brilliant book written in 1947 had been completely forgotten by 1963 and was never republished.”

Tonight, Friday, April 29, join us for a special event on nationhood, exile, and Southeast Asian history featuring seminal Indonesian novelist Leila Chudori and honoring the late Benedict Anderson with Vincente Rafael and Gina Apostol.

—

When I was in Jakarta in 1962–64, one of my favourite routines was to pay a weekly visit to a street famous for its long line of second-hand bookstalls. It was the perfect time to accumulate, quite cheaply, an interesting personal library. When the Dutch who had remained in Indonesia after independence were finally expelled at the end of 1957, many of them sold off their libraries, which were too large and heavy to take back to Holland. Most of these books, some very valuable, were in Dutch, which few Indonesians under twenty-five understood any longer. In the early 1960s, inflation was already very high, so that people living on fixed salaries could only survive by corruption or by selling off possessions, including old books and magazines. Commonly, when elderly book-collectors died, their children, uninterested in their parents’ hobbies, did the same thing with their inherited libraries.

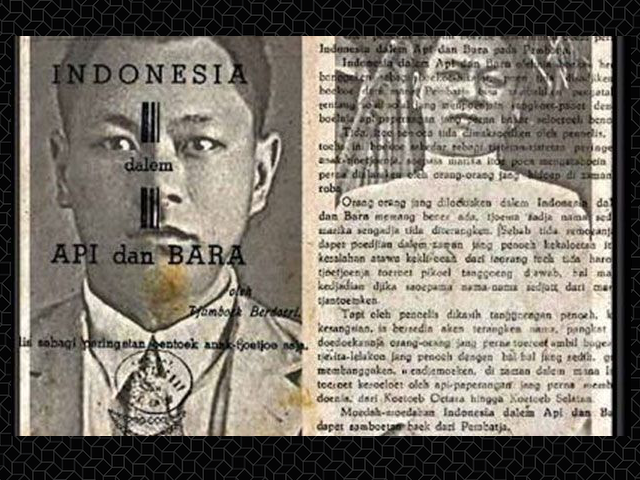

One day, I found an extraordinary book called Indonesia dalem api dan bara (Indonesia in Flames and Embers), published in 1947 in the Dutch-occupied East Java city of Malang, by a writer using the pen-name Tjamboek Berdoeri, which means ‘a whip into which thorns are imbedded.’ It contained a brilliant, funny, and tragic first-person account of the writer’s experiences during the last year of the old colonial regime, the three and a half years of the Japanese Occupation, and the first two years of the armed Revolution (1945–47). Even today, it is still far the best book written by an Indonesian about this period of great turmoil.

When I asked my friends about the book, it turned out that only one of them had ever heard of it, let alone read it, and this person had no idea who ‘Tjamboek Berdoeri’ really was. I tried many times to get a second copy, but with no success. I promised myself that one day I would try to track down Tjamboek Berdoeri, but had neither the time nor the contacts to fulfil this promise before I was expelled from Indonesia in 1972. But I did not forget it. When I returned to Cornell in 1964, I donated my copy to the library’s rare books section, fearing that no other copy existed in the world. (Only forty years later did our expert librarians track down two copies in Canberra, and one in Amsterdam.) When I was finally allowed back into the country in 1999, I decided to renew my search for Tjamboek Berdoeri, and to solve the mystery of why a brilliant book written in 1947 had been completely forgotten by 1963 and was never republished.

With the help of my Javanese labour activist friend Arief Djati, and after many false starts, I eventually discovered that Tjamboek Berdoeri was Kwee Thiam Tjing, a well-known Sino-Indonesian journalist and columnist during the final twenty years of the Dutch colonial regime. With the additional help of some Sino-Indonesian friends, the two of us managed to get the book republished in 2004, with a huge number of footnotes to help modern readers with no experience of the colonial era.

Kwee—we got used to calling him Opa (Grandpa) among ourselves—came from an old East Java Chinese family stretching back many generations. Born in 1900, he was among the very few Chinese youngsters of his time to be educated wholly in Dutch-language schools, but he never went beyond high school because there was no university in the vast colony. (At the end of his life he laughingly recalled how he often got into fights with his Dutch and Eurasian classmates, and thus was one of the very few ‘natives’ who had the luck to beat up a white boy now and then without being punished.) After a brief and unhappy experience working in an import-export firm, he turned to journalism, where he enjoyed immediate success. He worked for various newspapers till the arrival of the Japanese, who suppressed the entire press except for a very few newspapers sponsored by the military authorities themselves.

During the Occupation and after, he worked as the head of a local branch of the Japanese-installed Tonarigumi neighbourhood association, officially created in 1940 for mutual help and national mobilizations, but originally born out of the Gonin Gumi of the Edo period, also set up for mutual help but mainly for spying on behalf of the authorities. (This set of associations still survives today in the Indonesian term Rukun Tetangga [Neighbourly Local Group].) He did his best to protect Dutch women and children in his neighbourhood when their men were imprisoned and often killed.

After 1947, we largely lost sight of him until 1960, when he went abroad for the first time in his life, following his daughter, her husband, and children to Kuala Lumpur. In 1971, he returned to Indonesia, and began to write a serialized autobiography for the Indonesian newspaper Indonesia Raya, which was banned by Suharto in January 1974. He died a few months later. Arief and I edited the serialized stories into a successful book, published in 2010 with the title Mendjadi Tjamboek Berdoeri (Becoming a whip with thorns). The more research we did, the more the mystery of the disappearance of Kwee’s 1947 masterpiece became understandable. We concluded that there were two primary factors, which are so interesting that they are worth detailing here.

The first was that Indonesia dalem api dan bara is written in an extraordinary combination of languages. While the basic language is Indonesian, parts are written in the Chinese dialect of Javanese used in East Java, and the text includes many phrases in a cunning parody of colonial Dutch and Hokkien Chinese, as well as a sprinkling of words in English and even Japanese. The one language Kwee never used was Mandarin. He was proud of the fact that he could not read Chinese characters, and felt himself to be an Indonesian patriot. He was sent to jail in early 1926 for defending an unsuccessful rebellion by the Atjehnese of north Sumatra the previous year. In late 1926, the young Indonesian Communist Party started a hopeless rebellion, and Kwee watched the cadres enter Jakarta’s Tjipinang prison just as he was being released. He had been imprisoned for political reasons by the colonial authority a few years earlier than Soekarno, who in 1945 would become the first president of Indonesia.

The use of all these languages (which makes the book almost impossible to translate) was not casual or random. Kwee typically switched languages for satirical purposes, or to give a flavour of the conversation of the people he observed during those years. Sometimes he would also use the technique for poetic or tragically ironical purposes. For example, in one place he uses the complex expression ‘Of Romusha, of Tjaptun.’ It is a mixture of the doubled Dutch word ‘of ’ (meaning ‘either/or’), the Japanese ‘Romusha’ (forced labourers recruited during the Japanese Occupation) and the Hokkien ‘Tjaptun’ (ten guilders). It was a bitter remark, saying that ‘money is the best lawyer in hell’. Elsewhere, he describes a grim scene in which revolutionaries are torturing or killing fellow Indonesians suspected of spying for the Dutch. He writes gruesomely that the sound of the battering of the victims’ heads was like that of the metallic kenong and kempul (key instruments in the Javanese gamelan orchestra).

The second factor was a consequence of the Republic of Indonesia’s entry into the United Nations, accompanied by the Republic’s efforts to create a modern state worthy of international recognition. On the one hand, the new state, proud of its national identity and ‘world status’, successfully imposed a monopolistic version of Indonesian, which even during the National Revolution had been variable, depending on the social or regional backgrounds of its speakers. The state now frowned upon any contamination by other languages, including even Javanese. The spelling system was also standardized—something the colonial regime had tried to impose without much success. Hence Kwee’s spectacular cosmopolitan polyglot prose was no longer acceptable. On the other hand, the state’s education apparatus peddled a version of pre-1950 history which almost completely ignored the role of the Chinese minority, and insisted on a heroic past for the Indonesians, and a diabolical one for the Dutch.

Kwee’s book is clearly written by a patriot, but also by a clear-eyed humanist. In it we find excellent, idiotic, pitiable and repulsive Dutch, cruel and tender-hearted Japanese, corrupt and generous Chinese, selfless Indonesian patriots, and sadistic ‘revolutionaries’ who tortured and murdered some of Kwee’s own relatives on the eve of the Dutch attack on Malang in the summer of 1947. In the political atmosphere of the 1950s and ‘60s very few people from any group wanted to read an honest, disconcerting, and complicated book of this kind. So, to use a modern phrase, it was ‘disappeared.’ Later, the Suharto regime’s heavy repression of the Chinese community—shutting down their press, suppressing their schools, banning much of their writing and excluding them almost completely from politics—made the ‘disappearance’ still more profound. (In the thirty-two years of his dictatorship Suharto never gave a Chinese a ministerial post till just before his fall. On the other hand, he cultivated the dozen or so Chinese billionaires who had no political power at all.) Only after the downfall of the regime was it possible to have Kwee’s masterpiece republished, and even, to some extent, appreciated.

What I hope to do now is to write something I have never tried: a literary-political biography, largely based on Kwee ’s autobiographical writings and the several hundred articles we discovered he had written between 1924 and 1940. Its main focus will not be on Kwee’s literary and political activities as such, but rather on the interlocked relationship between the two. The idea is to try to reimagine the ‘colonial cosmopolitanism’ of that era, created by a huge tide of urbanization, capitalist expansion, new means of communication and rapidly expanding education (including self-education). Kwee spent most of his time in Surabaya, the large coastal commercial centre which was full of Javanese, Madurese, Outer Islanders, Dutch, Hokkiens, Hakkas, Cantonese, Jews, Yemenis, Japanese, Germans, and Indians, and included Muslims, Christians, Hindus, Taoists, and Buddhists. They picked up bits of each other’s languages for use when they needed to interact, read each other’s newspapers, and had sometimes friendly, sometimes hostile relations with one another. In many ways it was a perfect environment for cross-cultural and cross- language creativity.

Excerpted from A LIFE BEYOND BOUNDARIES by Benedict Anderson by arrangement with Verso Books.