From Pearl Buck’s “The Good Earth” to the FBI files of HT Tsiang, a journey into the archives with Hua Hsu

June 7, 2016

In a dark archives room in the basement of the UCLA library, Hua Hsu stumbled across a stack of FBI files filled with testimonials and amateur literary criticisms regarding the radical writer and troublemaker HT Tsiang. It is in these files that Hsu found the story of his own book, A Floating Chinaman, the name of a lost manuscript written by Tsiang. At a time when writers like Pearl Buck depicted the Chinese as “mellow, thrifty, and shy,” Tsiang sought to transcend all essentializations of identity and float above them, erratic and untamable. It is within Tsiang’s subversive nature that Hsu found inspiration for his own work, a process which he chronicles below.

Hua Hsu will be joining us for a celebration of his new book this Wednesday, June 8, at 7PM.

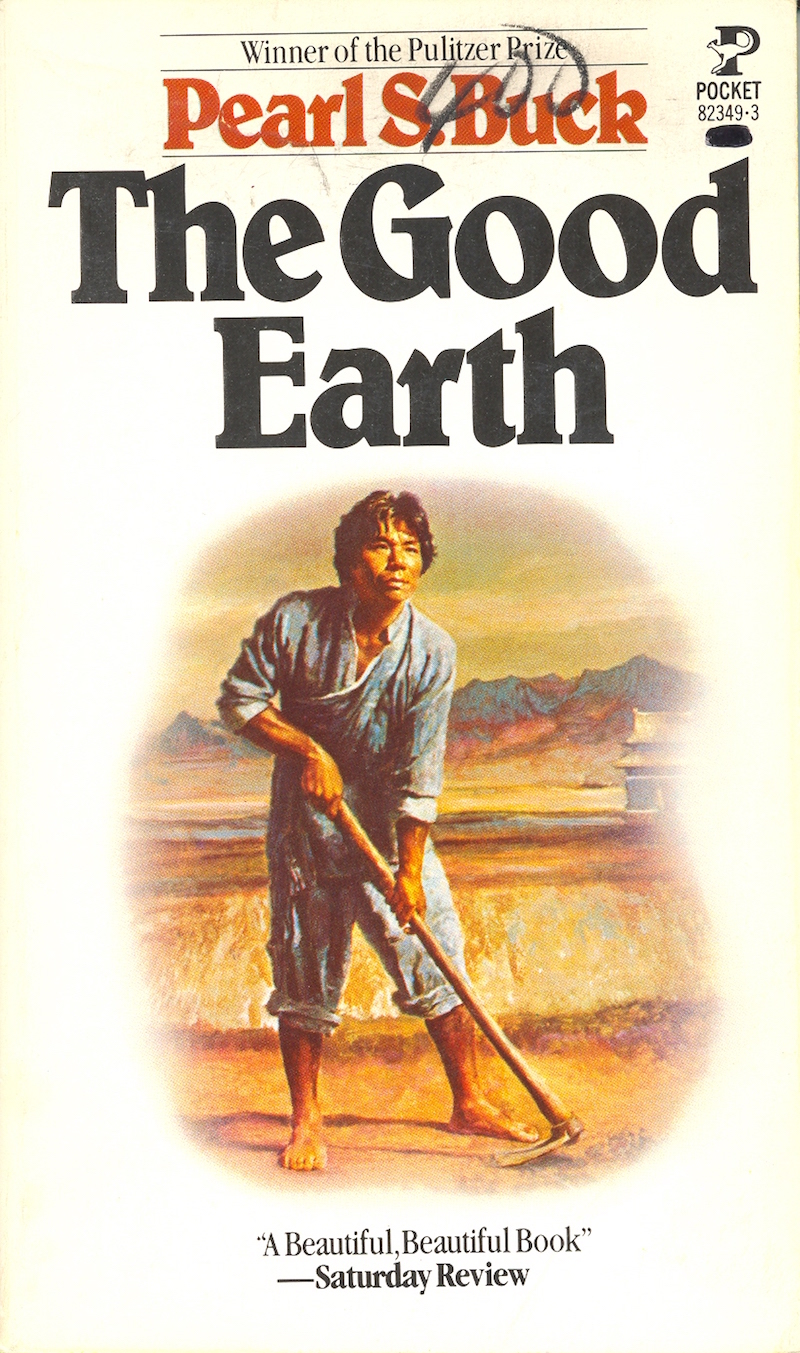

Paperback of Pearl S. Buck’s “The Good Earth”

I was introduced to Pearl Buck’s The Good Earth when I was in middle school. It was the high point of 1990s multiculturalism and we were required to take a class called “Global Issues.” One day, our well-meaning teacher asked everyone to pair up with a member of the opposite sex. She led us outside and instructed us to walk to the bleachers and back, only the boy—playing the role of the husband—was to remain ten paces ahead of the girl—the wife. We did as we were instructed. That, our teacher explained once we were back in our seats, is what it is like in China. She began passing out copies of The Good Earth. The strange thing—one of many strange things, I guess—is that I don’t recall the women in Buck’s novel actually walking ten paces behind the men. I had to return the school’s copy, but I found this image of that edition on the Internet.

No individual played so significant a role in shaping American views of China. The Good Earth became a cultural phenomenon. Buck’s tale of China’s honest, down-on-their-luck farmers eventually made its way to Broadway and then a successful 1937 film adaptation. In the coming decades, Buck would publish more than 70 novels, almost all of them about China, and receive more than a dozen Book of the Month Club nods. She became a sought-after lecturer on everything from human rights to women’s rights to segregation to the prospects for war. She helped overturn the Chinese Exclusion Act in 1943. Succeeding generations—my middle school teacher among them—continued consulting The Good Earth as an introduction to Chinese civilization.

I had always been interested in representations of Asia and its people, particularly those produced from without. Despite my initial skepticism toward Buck, I came to find her fascinating. She wasn’t an opportunist; China was all she knew. She was raised there, she spoke the language, and, most importantly, she resisted the condescending view most missionaries (like her parents) had toward the common “heathen.” She identified with Chinese culture and its people. In fact, she saw her novels as correctives to all the terribly racist and xenophobic portrayals that cluttered American bookshelves. Not that she could control how this book would circulate, or the way it would be introduced, decades later, to a middle school class in the Bay Area.

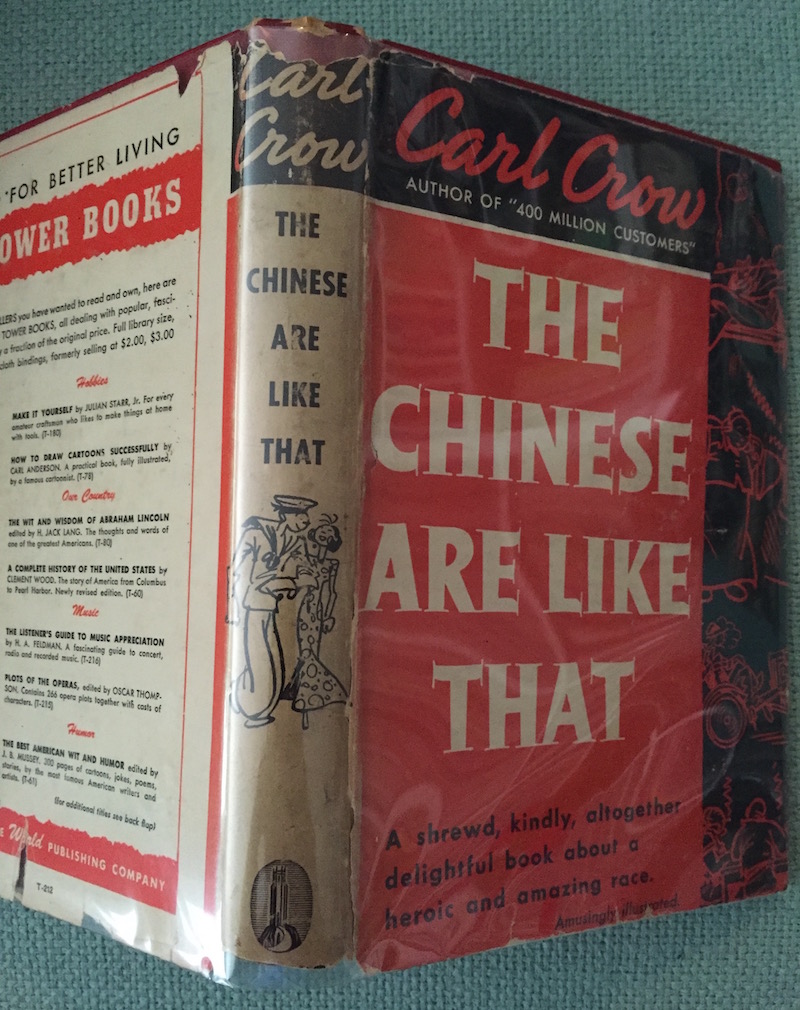

Dust jacket for Carl Crow’s “The Chinese Are Like That”

I began thinking about my book not just as a history of Buck, but as a survey of her effects. Her comfort speaking and advocating on behalf of the Chinese made Buck herself a character in a larger, interwar drama evolving along the transpacific circuit. Throughout the 1930s, her popular celebrity and political influence coalesced into a rare kind of authority. All of a sudden, Americans became interested in the figure of the “China expert.”

The success of The Good Earth helped create a new audience for books about China and, in the subsequent decade, fellow writers like Carl Crow, Alice Tisdale Hobart, and Edgar Snow would benefit from the heightened stature given to those who could comment on this distant land. While some, like Crow, had already been reporting from China since World War I, it was The Good Earth that expanded the market for their books. In fact, it’s often argued that the only true rival to her influence was publishing magnate Henry Luce—and, compared to Buck, he had an entire fleet of magazines at his disposal.

At some point, I started collecting books from the 1930s meant to soften China in the American imagination. They all seemed to rehash the same tropes—mellowness, thrift, shyness, a kind of pre-modern innocence. Some of the most interesting observations were produced by Carl Crow, a journalist turned marketing wizard, who is often credited with introducing Western-style advertising to China. He’s also the one who popularized thinking of China as a land of “400,000,000 customers”—the title of his most famous book, published in 1937.

I began thinking about how advertising works by selling us a better version of ourselves, and maybe that was a way of thinking of the idealized, newly modern, Chinese “customer” that Crow described in his books. This is The Chinese Are Like That, a breezy guidebook to the Chinese spirit, and a reminder that even someone like Crow, who was exceedingly sympathetic toward China and its people, couldn’t help but lapse into massive, often condescending generalizations.

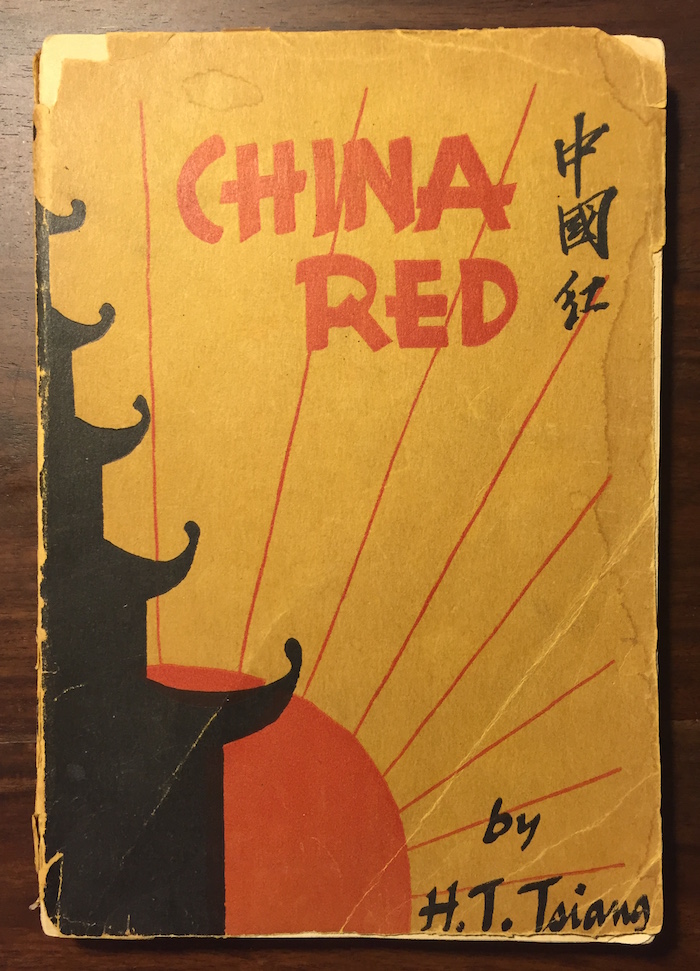

HT Tsiang’s China Red

So—I was working on a book about Pearl Buck, her astonishingly huge effect on how Americans received China, as well as the circles of writers and journalists who also contributed to this emerging conversation. But I kept wondering about dissenting voices.

I had heard about H.T. Tsiang, thanks to the diligence of the literary scholar and poet Floyd Cheung, who had helped republish Tsiang’s And China Has Hands in the early 2000s. Tsiang worked for a spell in the Chinese government before moving to the United States in the 1920s. He was ostensibly here for graduate school, but he fell into the Proletarian Arts scene and harbored dreams of becoming a writer.

I never read any of Tsiang’s work until one day when I was digging around for stuff at the main branch of the New York Public Library. I requested Tsiang’s China Red, his first novel, which he self-published the year The Good Earth came out. It looked to be an epistolary novel detailing the long-distance love affair between a Chinese student in America and his beloved back home. But as I flipped through the pages, it seemed as their relationship only consisted of short debates on American racism, the so-called expertise of Americans in China, and the future of Communism. It was pretty strange. I photocopied it and took it home to read. I wasn’t sure what Tsiang’s beef was but it was clear that he had one.

As someone who loves possessing things, I ordered a copy of China Red on eBay. When it arrived, I was stunned to see that the back cover, which the library’s copy was missing, featured excerpts from two publishing house rejection notices. I had never seen negative blurbs before. Then I noticed that the copy I had was signed. I started buying all the first-edition Tsiangs I could afford, and I realized that he had woven stinging disses of Buck, her cohort, and the very idea of the China expert into his next two novels. It felt wild to finally find someone with such an impassioned and sustained criticism of the China-watching establishment. (In contrast to Tsiang’s naysaying, the “Chinese Digest,” the first English-language Chinese American newspaper, published an entire Good Earth-themed issue in 1937. A few years’ worth of the “Digest” are available online, and they are incredible.)

All the first-edition Tsiangs I found featured negative (or, at best, lukewarm) endorsements. And, because they were largely self-published and sold hand-to-hand throughout lower Manhattan, they were all signed as well.

Photograph of HT Tsiang

It should be noted that Pearl Buck herself wasn’t immune to jealousy. Her grip on the crown loosened as the cold war approached. Just as Tsiang had dissed her in his writings, she turned around and wrote an entire novel fictionalizing the life of Henry Luce, her rival as America’s most powerful China expert, as a sad, impotent affair. It’s one of the unexpected themes of my book. Failure, competition, and jealously drive art and creativity just as much as beauty or truth.

I became obsessed with Tsiang’s animosity toward Buck and what he perceived to be the establishment. And this obsession manifested, in part, as a series of eBay searches. This is my favorite photo of Tsiang, which I bought maybe ten years ago.

After his literary career stalled—and after he was nearly deported (you’ll have to read the book to find out more)—Tsiang moved to Los Angeles and became an actor. Sometimes, “acting” meant avant-garde dinner theater involving “Hamlet” reimagined with no clothes on. Other times, he paid the bills playing the inscrutable “Oriental” in movies and TV shows. In a funny, ironic twist he even acted in a movie that had been written by Pearl Buck. I don’t know what show this is from but I’ll assume that this actress’ utter bafflement toward him is a look he saw quite often in life.

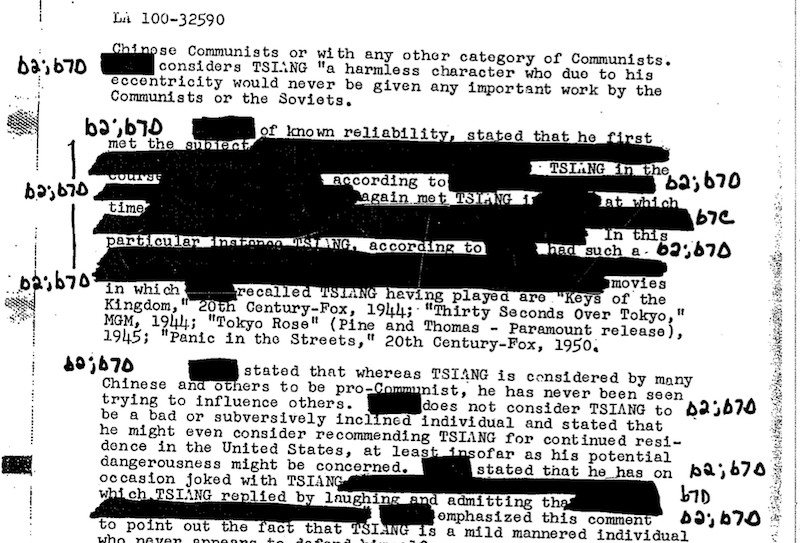

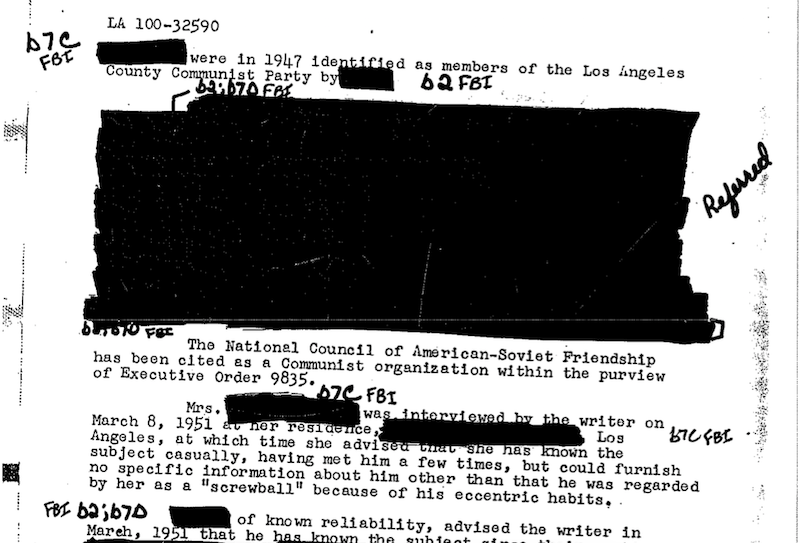

FBI Files on HT Tsiang

I was doing some research on Tsiang’s life in Hollywood and I decided to see if there was anything in the archives at UCLA, near where he lived. It turned out that the late labor historian Josephine Fowler had donated her papers to the library, and they contained a file on Tsiang.

When the librarian delivered the files to me, I was surprised by how heavy they were. There isn’t that much information about Tsiang out in the world, and I thought I had come across all the primary documents available in the United States. It turns out that Fowler had obtained Tsiang’s F.B.I. surveillance files. As a tireless self-promoter, he probably told anyone who would listen that he was some sort of big time lefty author. When he arrived in Hollywood in the early 1940s, he had inadvertently stepped into a world where anyone with even the faintest Communist affiliation had to be tagged and tracked.

The files, which compile testimonials from his friends and fellow travelers, were tremendously moving. They described him as funny, cranky, lazy, indefatigable. It turned out he was more than a visionary loner, wandering the streets and badgering strangers into buying his self-published odysseys. He was the life of the party, absolutely unforgettable. Maybe he was even the threat to the establishment that he once fancied himself to be.

I still remember sitting in the darkened archives room, hoping this file would never end. At one point, various agents from the FBI and INS start describing his poems and novels and performing amateur literary criticism, reading between the lines of those books he had published back when he lived in New York. I felt proud. He had found his readers.