Lessons on how life in the US was worth much more if spent in solidarity with those who suffer at its heel

March 18, 2014

The Counterculturalists is a new series in The Margins that looks at Asian American or ethnic identity as an alternative, rebellious, uncategorizable subculture, an avant-garde in both politics and aesthetics. Through interviews, original essays, multi-media, and criticism, we’re featuring writers and artists whose work calls us to the margins. First up is cultural critic and historian Vijay Prashad, with a remembrance of campus organizing around the global movement to end apartheid in South Africa. Check out more in the series here.

—

The first time I saw a copy of the Student Anti-Apartheid Newsletter was in 1986. I was in the cluttered office of my faculty adviser at Pomona College, Sidney Lemelle, a professor of history. There was a typewriter on his desk, and books on his shelves cascaded into piles of books on the floor. Papers sat all around, picked up, shuffled, read, re-read, marked-up. Among them were cyclostyled sheets from myriad activist organizations, most having to do with Africa’s turbulent on-going liberation struggles in the 1980s. In this deliberate jumble lay the newsletter of the American Committee on Africa. Lemelle must have tossed it to me or I wouldn’t have picked it up. It had the dull look of activist papers of that era: small, squashed type with letters and entire lines jammed into one another, and a small outline map of Africa in the top left corner. The newsletter kept US-based activists informed about the politics of South Africa, and of other activists, including students, across the country, and lessons toward a better political climate (notably how to deal with racism within the movement).

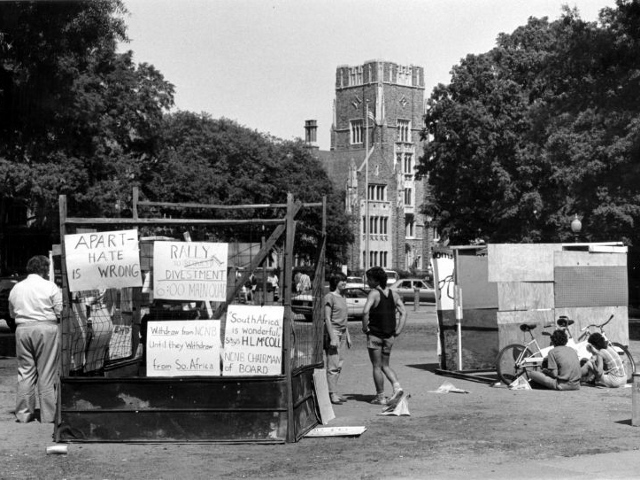

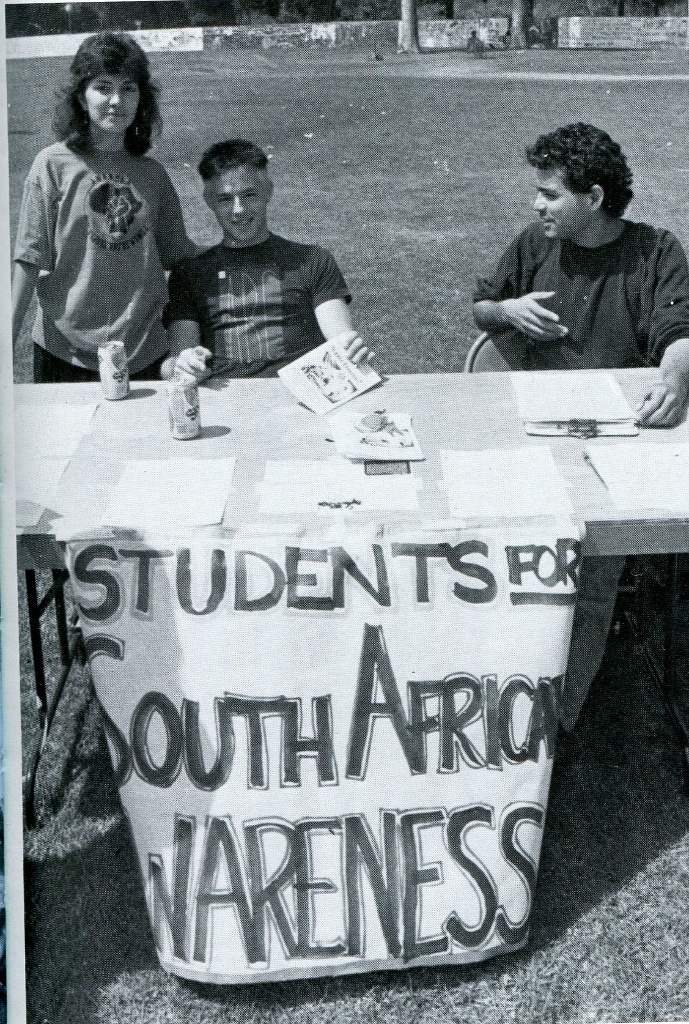

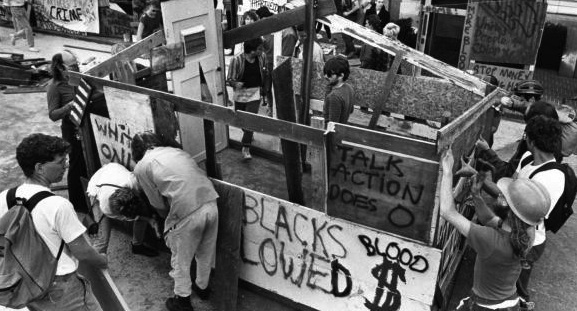

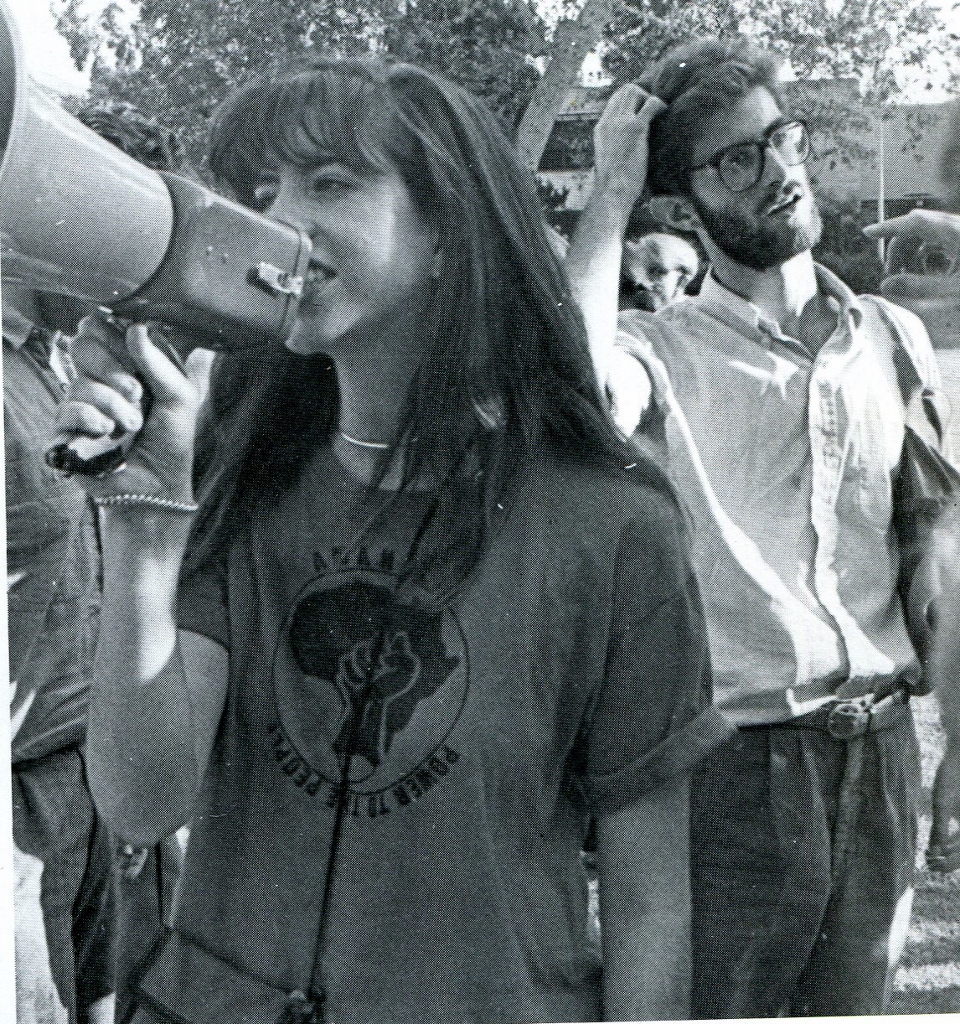

During the mid-1980s, a flurry of direct actions were taking place on US college campuses to demand the divestment of college endowments from funds that invested in apartheid South Africa. Protesters built blockades, staged sit-ins, constructed and defended shantytowns made of plywood, cloth, and cardboard, and mobilized large numbers of students for militant rallies. Our little liberal-arts college, with its large endowment, could not go unscathed.

However, nothing we did rivaled the scale of the protests at UC Berkeley, where on April 1, 1986, a fierce fight between the shantytown protesters and the police led to considerable mayhem on campus and numerous arrests. As the Spring 1986 Newsletter described the scene: “At 2:45am 200 policemen in riot gear began an assault on the shanties by arresting all legal observers and clubbing a press photographer who was hospitalized. Two hundred protesters defended the shanties by linking arms while a crowd twice that size built barricades to prevent police buses from getting on or off campus. Outraged by police brutality, demonstrators fought back with bare hands, bottles, and stones and prevented the buses filled with arrested activists from leaving campus till 7:30am.” This was not a picnic. It was a serious fight, and on July 18, Nelson Mandela’s birthday, the University of California Regents voted to divest the system’s $3.1 billion from US corporations and banks linked to South Africa. It was a significant victory, driven by students whose actions inspired the country.

The dominoes seemed poised to fall—colleges with vast holdings in apartheid South Africa such as the University of Texas ($770 million), Harvard ($500 million), Yale ($400 million), and Princeton ($200 million) were seen as collaborators with a racist state. The UC divestment vote, said Thabo Moeti, a South African student at UC Santa Cruz, “is another nail in the coffin of apartheid, but it is not the main nail, or the last one.”

Pomona had modest holdings in South Africa compared to the behemoths of higher education, and it had a commensurate protest movement. But for those of us who were involved, the movement produced an acute analysis of the hypocrisy of US institutions. Taking our cues from the wider movement, those of us at Pomona decided to set up a shantytown outside the college president’s well-appointed house. Ours was made up of a few camping tents and sleeping bags in which most of us slept. There were a few cardboard boxes, but these were not as functional as we amateurs in outdoor sleeping had assumed. The president, David Alexander, who had been at his post since 1969, had the demeanor of a patrician, carrying his Tennessee birth certificate as close to his heart as his Rhodes Scholarship to Oxford. During the height of the Vietnam War and the anti-war protests, Alexander affirmed the importance of the liberal arts education: “Our task is to winnow from the welter of changing values those transcendent values for which this college exists, so that while trying to move with society, Pomona College will help move society through education.” No wonder then that one night he came out to talk to us in the shantytown on his lawn. I remember him telling us that our presence was an irritation to his garden, and he hoped that we’d let him have at least one unbroken night of sleep. When he walked away he winked and said he was proud of our commitment to our beliefs.

Alexander’s pride in our efforts was not sufficient. Within a week, we faced a muted version of what our compatriots at the UC had to deal with. The shantytown was dismantled and there were arrests – it was quite orderly, but an arrest is an arrest. The message was clear: the United States is not as committed to the values of freedom and justice as it is to the right of the rich to do with their wealth as they will, and the right of the US to dictate policy to the people of other nations. Our group was small. Many of us were involved in allied struggles, notably with the Committee in Solidarity with the People of El Salvador (CISPES), whose campus leader, Noel Rodriguez, is now a labor organizer. On March 21, 1986, during the 26th anniversary of the Sharpeville Massacre in South Africa, activists around the country linked the opposition to US support of apartheid South Africa to US funding of the National Union for the Total Independence of Angola (UNITA) and to the Contras in Nicaragua. The links between the various struggles against US imperialism seemed organic, all rooted in disenchantment with the sugary rhetoric of US power, cloaked in “human rights” but bathed in the blood of the Contras, UNITA, the South African Police and the Salvadoran death squads. I remember Noel’s unfazed passion and his bravery. It took people like him to articulate a new sense of how to live in the US, to teach the rest of us that life in America was worth much more if spent in solidarity with those who suffer at its heel.

Danger stalked even our small-scale activism. In the Summer of 1987 I vividly remember hearing news that Yanira Corea, then a 24-year-old volunteer at the CISPES office in LA, was abducted by a death squad outside the office. Her abductors carved the letters “EM” on her palms – for Escuadrón de la Muerte or Squadron of Death. While she was raped the men interrogated her about her activities in the CISPES office and about her brother who was a union activist in El Salvador. A few days later Marta Alicia Rivera, another activist, received a death threat that ended with the death squads’ tag line, “Flowers in the desert die.” Not long after, Father Luis Olivares of Our Lady Queen of Angels Church, a sanctuary for Salvadorans and other Central American refugees, was targeted by the squads. We had gone from Pomona to the church to defend its status as a sanctuary alongside Father Olivares, who had already got used to danger and to threats to his reputation. The squads seemed to operate with impunity even in Los Angeles, and the police seemed more interested in arresting and deporting runaway political refugees who had hidden in Father Olivares’ church than in prosecuting those who had begun to intimidate our friends. Yanira’s life had become a nightmare – her small-scale work to raise awareness of the atrocity that was the El Salvadoran government had made her a threat.

In 1988, my professors Sidney Lemelle and Ruthie Gilmore organized a conference on pan-Africanism at Pomona. The most exciting part of the conference was that they had invited members of the African National Conference (ANC) and of the South-West Africa People’s Organization (SWAPO). These activists were to be under our care. I remember the hours spent in the little green house where students Elisabeth Armstrong, Marilyn Filley, and Filip Sirovy, a recent defector from Czechoslovakia, stayed. We were a full house with the SWAPO and ANC members in our living room. Filip, a left-handed pitcher for the Czech Black Horses baseball team, was petrified by the presence of members of what the US government considered terrorist organisations. But the ANC and SWAPO members mingled with us freely chatting while conference participants such as Robin Kelley, Maryse Conde, Vincent Harding, Paul Gilroy, Horace Campbell and others went in and out. At night, our old stereo would churn out-dated music as the old floorboards rattled to the bounce of the dancers and frightened the needle as it skipped beats on the turntable.

It was from one of the SWAPO activists that I remember hearing stories of the ongoing battle at Cuito Cunavale in Angola (September 1987-March 1988), where the South African Defence Forces had been defeated by the conjoint operations of the Angolan forces, SWAPO and Cuban fighters. He could taste freedom for Namibia, he said, and then for South Africa. All that petty work that we were doing seemed to be linked somehow to the momentous events in South-West Africa. At the front of the house, for the duration of their stay, sat a van with government agents taking their shifts. On the second day, one of the agents came to the door, introduced himself and used the toilet.

Pomona divested. South Africa threw off apartheid. El Salvador voted into power the Farabundo Martí National Liberation Front, the political arm in the country, supported by CISPES. SWAPO has been governing Namibia since 1990. An era ended. Struggles did not. They morphed. Reading old copies of newsletters and looking at old flyers help me revive memories of those college years, my first political campaign in the US. This was the America I became acquainted with–the hypocrisy and violence of its power elite and the decent idealism of its activists.

MORE IN THE COUNTERCULTURALISTS SERIES ON VIJAY PRASHAD:

“Break the Silence”: Cultural critic Vijay Prashad and legal scholar Aziz Rana discuss the legacy of multiculturalism, and what’s left of third-world solidarities.

“Talk of a Global Jim Crow”: Vijay Prashad at the Brecht Forum. Plus, how Kumar Goshal (1899-1971) carved out a theory of US imperialism in the African American press.