When we point towards the horizon and say this is the color / of our grandfather, we do not know for how long // the night will carry your shade or what winds / brought you here.

April 19, 2016

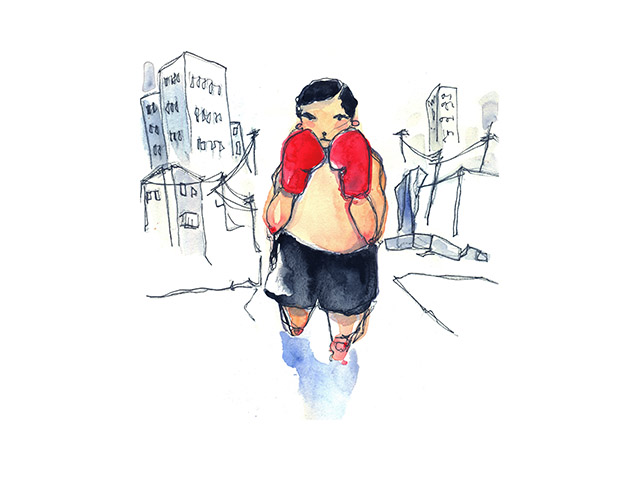

Grandfather as a Kaiju on Fire

A year later your body still burns, still sends your skin up

as embers and gives the sky its disposition. When we point

towards the horizon and say this is the color

of our grandfather, we do not know for how long

the night will carry your shade or what winds

brought you here once dormant in a starless

chamber close to our volcanos. The day you fell, dragged

down by the imaginations of engineers we tasted

your smoke, pocketed hairs that wrapped

our throats, the tooth we ground into fertilizer, jealous

you became a powder that made strangers virile.

Science did not think of you as a body

to bury but a house made of flames. When asked

about the sound of your collapse, how the dust peaked

after your body went slack, we said we knew him mostly

by his fire, by the blood that could not be lit.

The Greeting

In Walmart, in Macy’s, when my father’s eyes take

the shape of a moon I have not seen, one covered

in smoke or storm, I know that look, that urge to gauge

a prospective countryman with a phrase I cannot call

my own, that carries the flames of a distant

countryside, whose roads are colors he does not see

anymore, here, amidst all of this abundance. There,

my father and a stranger stand surrounded by the latest

trends in length and texture, talk about mortgages,

about the taste of the air in unbearable humidity.

To the ones who do not recognize my father’s call

as their own, forgive him this loneliness, the islands

he thought he heard rattling in your throat, the glaze

on your skin he mistook for salt and ocean,

for volcanos and birds and the bones of giants.

Forgive him the street and all of its fires, the flood

in which his sister is always drowning. Into my hand,

my father shoves a fist full of shirt with “Made

in the Philippines” printed on its tag. Perhaps, we discuss

the murkiness under which such fabrics are produced.

No, the role of the son is not to strip such joy

from his father, who holds in his hand the horizon

as a second skin. Instead, how much pressure

does a needle need to penetrate this cloth,

to break the skin where a splinter rests?

When my father speaks, I dream of the color

of his tongue, how it contracts, isolated

in the darkness, enters the world already heavy

and blackened. I dream of all

the blood it takes to say hello.