The artist’s interactive graphic novel adaptation of Nam Le’s “The Boat” is an entry point to a conversation about refugees today

March 11, 2016

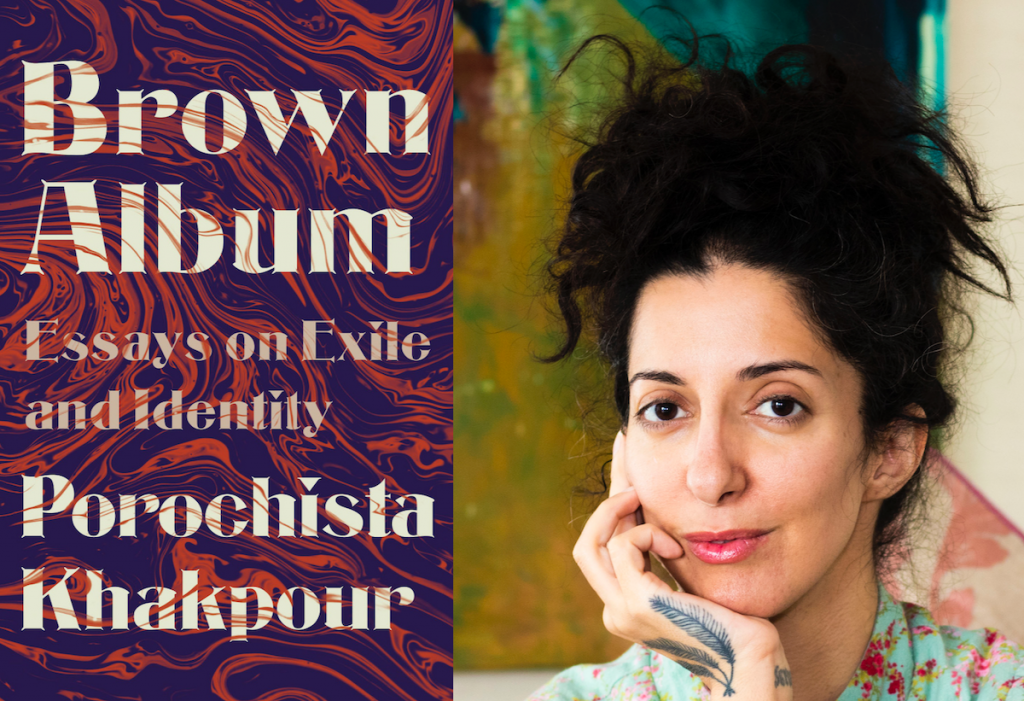

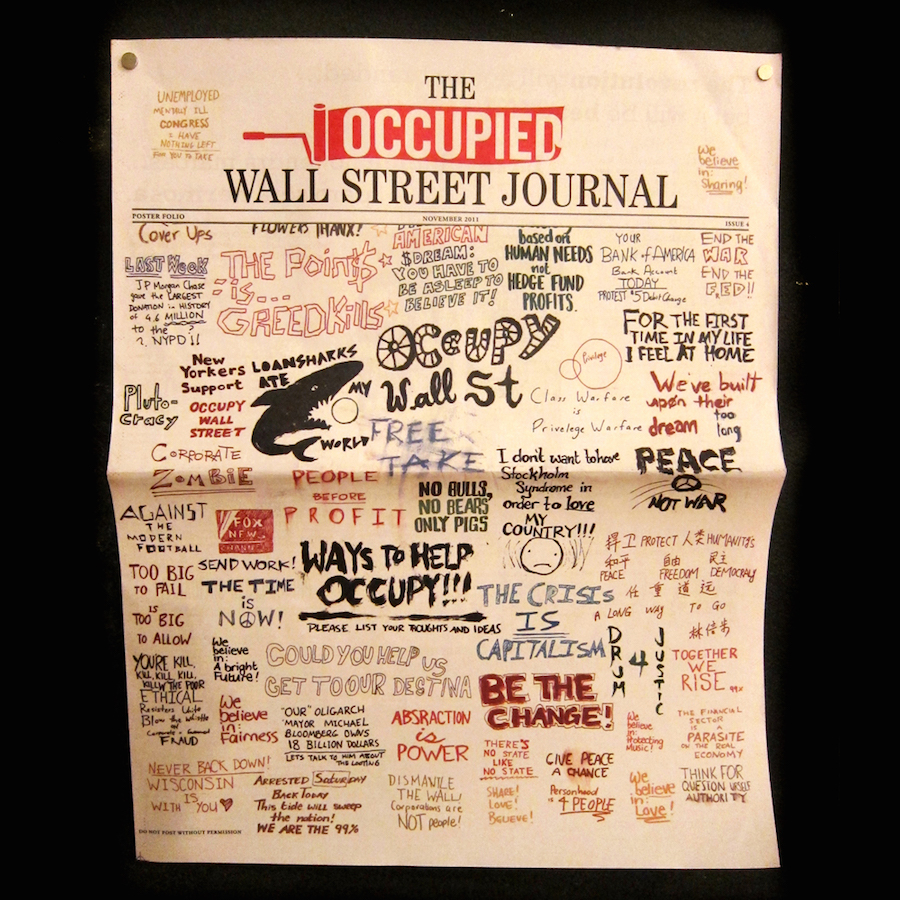

Matt Huynh has a way of drawing outside the lines, having crossed many of them over the course of his life. As an artist who regularly intertwines his graphic work with poetic and fictive narratives, he has inked everything from fashion magazine spreads to the cover of the short-lived Occupied Wall Street Journal. But one of his most ambitious works explores borders within, through the collective memory of Australia’s Vietnamese diaspora. Huynh channels family lore and collective memories of trauma in his graphic comic adaptation of “The Boat,” a short story published in 2008 by the Vietnamese-Australian writer Nam Le. Huynh’s brush strokes puts a noir spin on the scars of an inherited war.

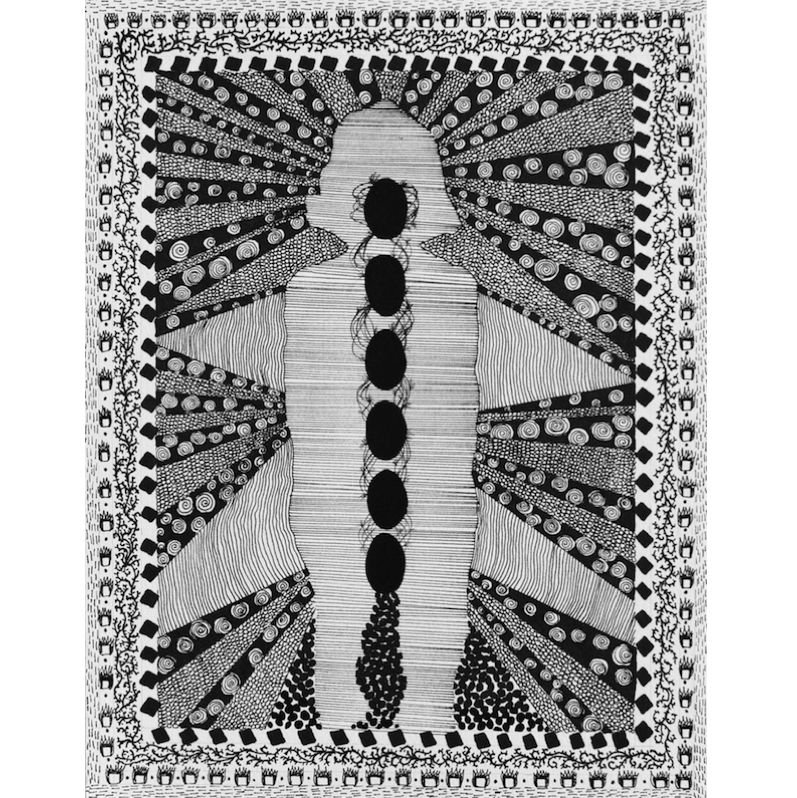

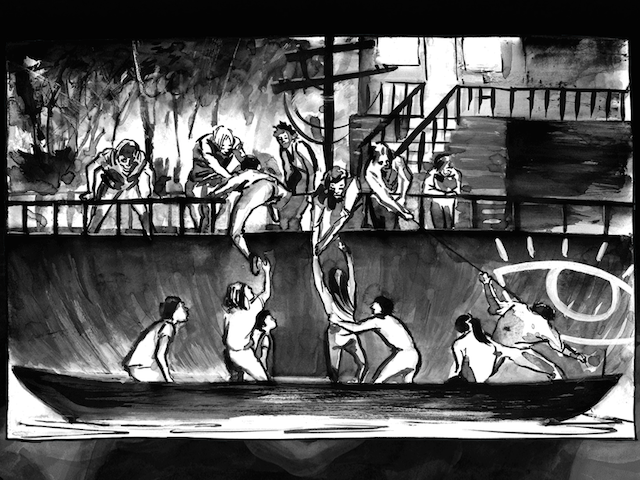

Though billed as an interactive presentation, The Boat condenses a harrowing journey over land and sea into a 20-minute “viewing experience.” At about the pace of a credit roll, the rhythm of the story revolves around a triangular relationship between a refugee mother, her son, and a woman she befriends in the throng of “boat people.” The strip is punctuated by gentle side-to-side swaying of the individual images, mimicking the rocking on the deck. Though the story is watched in real-time, scored over sounds of waves and wind, and propelled by an individual’s scrolling and pausing, the viewer feels swept along. There’s a sense of movement but each frame unfolds in monochrome analog, flowing at the heady pace of a subaltern zoetrope, with images of despair, redemption and emancipation pulsating at just the right frequency to bring a cumulus of still lives into animation.

But when the narrative zooms into individual frames, the characters on deck find themselves adrift in memory. Two women war quietly over the body of an ailing boy. The custody battle amid a sea of deprivation cuts against the hierarchy of needs, and an increasing maternal instinct swirls around a murky back story: the protagonist Mai is revealed through flashbacks of a winding journey, from a home broken by conflict, through a series of hiding places, and onto a teeming refugee boat. Eventually she becomes an adopted mother of sorts to the boy, but the family she’s inherited reincarnates harrowing memories of violence as the boat hurtles into the unknown.

The nonlinear narrative that scrolls through the frames traverses the senses: “Inside the hold, the stench was incredible, almost eye-watering. The smell of urine and human waste, sweat and vomit. The black space full of people. Bodies upon bodies. Eyes and eyes and eyes.”

Not coincidentally, “The Eye” is also the name of the migrant ship on which they travel, with an eyeball mascot lashed menacingly to the ship’s hull. The Boat teeters between these two counterpoised realities: the tragedy of being ignored and neglected, and the terror of feeling constantly watched, never able to shake the grip of continual vigilance.

When it was featured by an Australian broadcaster SBS during the 40th anniversary of the Fall of Saigon (or the 40th birthday of the Vietnamese refugee crisis), The Boat was hailed as both an innovation in storytelling and a political statement on historical reconciliation. Now that resettlement has reached middle age and Cold War fog has lifted, stories of suffering and survival across the diaspora are being revisited by a new crop of second-generation young activists. Artists like Huynh inherit and reassemble their past in a contemporary post-colonial light for a broader public—including many whites who are grappling with a new “refugee crisis.” Just as masses of Vietnamese refugees fled to Australian shores forty years ago, today, new refugees from other countries across Asia and the Middle East, refugees from other conflicts, are seeking asylum again. Unlike the previous generation of refugees, however, they are thwarted by a hostile conservative government, byzantine, highly politicized asylum claim process, and a detention system widely decried inhumane.

Yet for his commemoration of the Vietnamese experience, Huynh says he’s heartened by the general positive feedback The Boat has received from a mainstream international audience, both for its artistry and its technological ambition (he worked with a digital media team to sculpt the code and cinematography to evoke a multidimensional narrative). Perhaps that’s because it refers to current events only elliptically through history. Besides, as a work of storytelling, he adds, “I also realize that it’s a project that’s quite hard to criticize. It’s quite hard to criticize something that is about a very vulnerable people… content-wise. Form-wise, it’s hard to criticize because there’s nothing really to compare it to.”

But being too unique to critique may in itself by the highest form of praise.

A singular multiplicity of gazes is at the core of Huynh’s approach to historical fiction. The Boat is in many ways the story of his own family; his parents fled Vietnam to Australia by way of Malaysia in the 1970s, a few years before Huynh was born. They were taken in as a humanitarian gesture by the Australian government as part of an international effort to resettle the escapees of Communist Vietnam in various parts of the West. Of the estimated two million Vietnamese who fled during that period, most went to the United States, but Australia now holds one of the largest Vietnamese migrant populations, around 226,000. Having lived among refugees as a native-born Australian for three decades, Huynh brought an intergenerational wisdom to the omniscient narration of “The Eye,” which in turn, he says, affords him a critical distance that allows Huynh the artist to get closer to subjects often not talked about in his own family.

“When I made my own stories,” Huynh says, “although they were based on my parents’ experiences…the kind of openness to which we discussed like those stories in the family was pretty non-existent … It’s a trauma, and it’s not something to be relived.” But when adapting another historical work, he continues, the project became “kind of an excuse for me to look directly at that history and look at it from another perspective with the benefit of someone else’s imagination and research and craft because I couldn’t access that directly just by talking to my immediate family because it’s something they wanted to move on from.”

But Huynh’s adaptation of the Vietnamese Madonna tale isn’t necessarily ennobling. The flashbacks to jungle hideouts and an underground network of helpers are interspersed with bleaker scenes: writhing knots of bodies ooze into each other in the hull. Figures of corpses, ghosts and the living mesh in gradients of gray that match the sky and sea—cut momentarily by a surreal burst of flower petals—so even a horizon of hope seems impossibly bleak.

Huynh has brushed across his own parents’ refugee story in an earlier graphic novel, Ma, but the characters are more representational than autobiographical. As a child of the diaspora, he is still working out how the refugee as a historical subject connects to his own background: “It challenges me to ask how far down I can look into it and still feel connected to it.”

Now a Brooklyn migrant, Huynh has produced commercial designs ranging from a Lautrec-style concert poster for Phish to an astronaut-themed smartphone shell. Much of his work deals with imaginary landscapes: an animation for the Brooklyn Academy of Music carries a boy from a galloping horse to a zooming rocket over an atmospheric rock soundtrack. In a mural installation in New South Wales, a psychedelic glass seascape at the Cabravale Leisure Centre diagrams the contents of a sperm whale’s stomach, layering a whimsical cross-section on a translucent netherworld.

His work typically draws on themes of alienation and displacement, so that the same eye that trains on the migrant mother in The Boat pans across the cityscape of Harri and Some Change, a 2013 web-based story tracing the adventures of a “runaway” to New York, whose fantastic yarns of urban living unravel into a mire of confusion.

As an illustrator, Huynh prefers to let the diaspora speak visually by revealing what is hidden. In one of his earlier comics on Sydney’s Chinatown, “Double Dragon Kung Fu,” the step-by-step preparation for a New Year’s parade unfolds like a martial arts instruction manual. It’s a lyricized self-training coursebook, starting from spartan aerobics and building up to a full-fledged lion dance in a lavish banquet hall, and hand-building their own stage—a forest of slim pillars topped with tiny platforms, between which the lion dancers will spring nimbly in glittery furry pantaloons, the whole team melding into a singular mythical corpus. The lions lunge and bow in imperial splendor, but soon the team dissembles into the sum of its parts—a circle of friends, perched on a new horizon, bound by something deeper than tradition.