“Since their submission was purely auditory, no one at Sprite realized they were Asian American.”

July 16, 2012

When the Chinese American rap trio the Mountain Brothers formed at Penn State University in the early 1990s, they were already following in the footsteps of older, pioneering hip-hop artists of Asian Pacific Islander descent. That included 2 Live Crew’s Fresh Kid Ice (Chinese/Trinidadian) and the L.A.-based family group Boo-Yaa T.R.I.B.E. (Samoan); even the salsa/soul star Joe Bataan (Filipino/Black) had recorded a minor rap hit back in 1979 (“Rap-O, Clap-O”). However, the Brothers became heralds of a younger generation of Asian American hip-hop acts, marking a shift away from the overt identity politics—but oft-amateur aesthetics—of older, college-originated groups such as Yellow Peril (of New Brunswick, NJ), and Fists of Fury (of San Francisco).

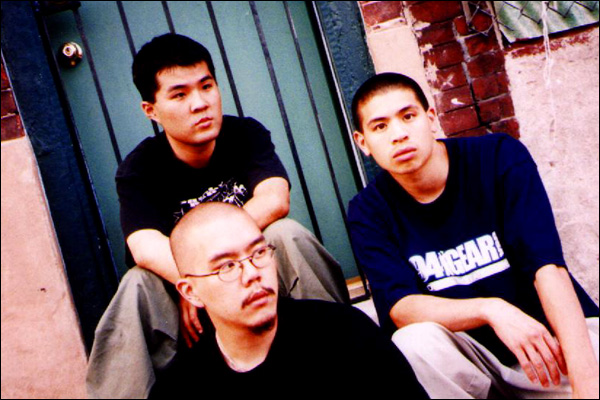

Instead, the Brothers’ Scott “Chops” Jung, Steve “Styles Infinite” Wei, and Christopher “Peril-L” Wang came of age with hip-hop as a formative influence and their racial difference wasn’t as much a badge they wore on their (record) sleeves. In that respect, they had more in common with Southern California artists such as the Japanese American group in•cite and the Japanese/Filipino American partnership between Key Kool and DJ Rhettmatic, both of whom formed around the same time as the Mountain Brothers. For these artists, race was an unavoidable part of their identity but not the core of their artistic focus.

The Brothers released their first single, “Paperchase,” independently in 1996. However, their career took an unexpected national turn when, that same year, they won a national radio contest sponsored by the Sprite soda company. Since their submission was purely auditory, no one at Sprite realized they were Asian American. Soon after, Nike hired the group to provide background verses for a t.v. spot that featured various Nike-sponsored NBA stars—though once again, the Brothers were invisible to the viewer, just voices on a soundtrack.

This national exposure did help the Brothers get briefly signed to Ruffhouse Records, making them the first Chinese American rap act to work with a major label. However, Ruffhouse’s executives were uncertain how to market the group; one suggested they could wear martial arts outfits on stage and wield gongs. The Brothers parted with Ruffhouse but continued to release recordings by themselves or with other independents, including two full-length albums—Self: Volume 1 (1999) and Triple Crown (2003)—plus a smattering of singles. By their second album, the group had added a DJ, New York’s Rhodello “Roli Rho” Roque, a Filipino American from New York.

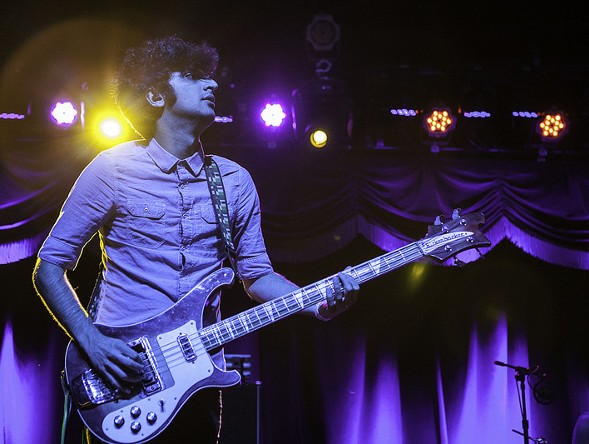

The Mountain Brothers disbanded soon after Triple Crown. Styles Infinite had worked on several solo projects before that album’s release; he’s now a teleradiologist in San Francisco. Christopher Wang remains in the Philadelphia area and works as a medical researcher. Only Chops stayed active in the music industry; based now out of south New Jersey, he’s produced for dozens of rap artists, including more recent collaborations with the Bay Area’s Keak Da Sneak and Houston’s Bun B.