‘She planted the tiny sleeping nuggets into the ground, as a small prayer. One day, they would metamorphose, escape into the world as something altogether different.’

August 21, 2015

Anwar Saleem and his family are Muslim immigrants from Bangladesh now living in Brooklyn. An owner of an apothecary, Anwar wins a dilapidated former crack house from the city of New York for a dollar and renovates it with the help of his Saudi friend and contractor Omar. Together with his wife Hashi, who runs a beauty parlor out of her garden apartment, they raise three young women—Charu, their rebellious daughter; Ella, their booksmart horticulture-enthusiast niece; and Maya, a runaway from an abusive father.

When he retreats into his “studio-tudio” to smoke weed, Anwar is haunted by visions of the “ghost” of Ella’s father who was killed after the war in Bangladesh. Charu immerses herself in hidden pleasures: handmade lingerie and Valium-induced makeout sessions with her uncle’s intern, Malik. Ella nearly drowns in her own night-time hallucinations, triggered by migraines, her indiscernible infatuation with Charu, or the stress of fighting insomnia. Maya fights for calm by sleeping in Ella’s bed.

Tanwi Nandini Islam’s debut novel Bright Lines is lyrical and rich. She pulls you out of a dreamlike state as fast as she throws you into it, until you come crashing into the concrete in front of 111 Cambridge Place in Clinton Hill. In the excerpt below we follow Ella, kept awake by her insomnia, into her beloved garden.

—Holly Hensley

Some said the backyard in 111 Cambridge Place had been a makeshift graveyard for the souls who overdosed on its grounds. The most popular tale was about a young boarder back in the seventies, born and raised minutes away, who grew up to be a jaded revolutionary, losing his way after his friends were imprisoned or started using. He belonged to the latter lot, but did not die during his binges, Instead, after a brilliant recovery from cocaine-induced cardiac arrest, the young man awoke in the hospital, feeling alive and refreshed. His brain had swelled up to twice its size and then shrunk back down. A miracle, said the doctors. But the young man had inherited a new affliction of the brain. You could show him a flashlight, a pencil, or a crack rock, and he could tell you what inanimate objects were. But he could no longer tell the difference between a rose or a radish or a puppy. He’d lost his sense of the living world.

When Ella first heard the story back in fifth grade, she’d been sure the young man had gone mad with confusion, unable to decipher whether to smell or eat or love something. Sometimes she thought that if the man had lost the ability to tell living things apart, his old relationships (to his dealer, his lovers, his friends) would have faded.

Then he would have no longer been haunted by his desires. It could be considered a blessing.

Ella broke soil with her shovel, scared of uncovering bones, though she knew everything had been upturned years ago during the renovations. It was three in the morning, three weeks after she’d arrived home for the summer. Insomnia worsened with the constant nightly presence of the sleeping girl, Maya, who had politely offered to sleep on the floor. Ella told Maya she didn’t mind sleeping outdoors, and slept on the hammock unless it rained. She hardly saw the girl anyway. Maya spent her days working and returned very late at night, only to sleep. Ella let her in through the sliding door in the kitchen. If her aunt and uncle were aware of the girl’s presence, they did not say anything to her or Charu.

Since returning home, Ella noticed just how preoccupied Hashi and Anwar always seemed to be. Her aunt lived in her salon, busy with summer weddings and beauty regimens; her uncle spent the brunt of the day in the apothecary and his nights upstairs in his studio, busy cooking up products and smoking pot, the smell of which wafted outside the attic window, straight into the backyard. He’d asked her if she wanted to spend some days working at the apothecary, but she declined.

As the rest of her family made their way to bed, Ella lay outside on the jute rope hammock tied between the hibiscus trees. First, Hashi and Anwar’s light went off, around midnight, and then Charu’s, an hour later. There had been no visits after Malik’s spill out of the tree, and Ella suspected the kid had been scared out of his wits. It all made for a very moody and short-tempered Charu, who had graduated from Brooklyn Tech and was now busy meeting up with school friends Ella didn’t know. At night, Charu kept to herself in her room, sewing her “independent” clothing line and blasting music until Hashi yelled at her to quiet down.

Around two thirty, Aman’s late-night television marathons dwindled, and Ella found some peace. Their uncle’s night-owlish ways would make it hard for Malik to enter undetected, as Aman took frequent smoke breaks in the garden. Malik wouldn’t risk it now, since he was Aman’s employee.

Just as everyone’s lights turned off, their tenant Ramona Espinal’s blinked on, enough for Ella to make out her silhouette in the window.

Ella dug a compost hole deep enough to fill with scraps from dinner and peat moss. Their garden was built in a circle. Anwar had first envisioned the garden as a compass. He’d built a wooden shed on the eastern side of the circular garden. Jutting out of this shed were birdhouses, drawing a menagerie of kestrels, meadowlarks, sparrows, bluebirds, and scarlet tanagers (a rare treat) for water and seed. He believed his compass became a vital hub in the birds’ migrations. Like an old-world astronomer, he placed a tiny magnetic needle in each water tray.

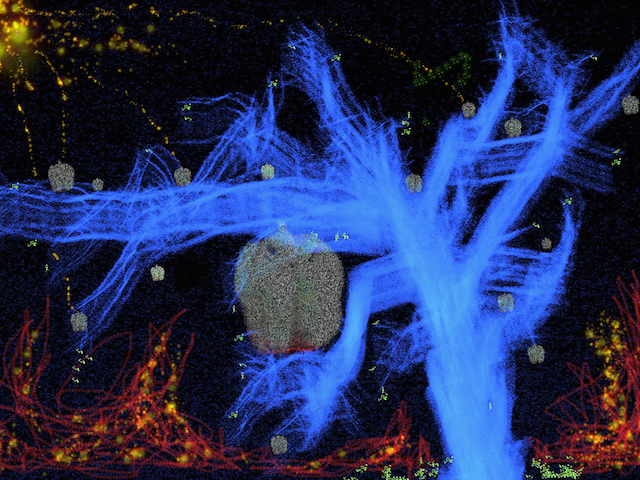

Inside the shed was a walk-in refrigerated vault lined with drawers holding hundreds of seed packets, resembling the card catalog in a library. Her uncle’s preoccupation with conspiracies had taken on a life of their own after her parents’ murder. It was a miserable period in his life, when he believed apocalyptic demise loomed around the corner. Depressed and mourning, Anwar stocked up on seeds, preparing for the end of days, fancying himself a builder of a botanical ark. By the time Ella arrived in the States, Anwar had already collected two hundred heirloom seeds.

Before Ella had left for her sophomore year, she an Anwar devised a plan to build a Linnaean flower clock. You could tell time according to blooming patterns, as different flowers opened and closed at different hours of the day. Sunflowers towered happily in the center, constant and uninformative as far as telling time was concerned. Anwar had planted morning glories, field milk thistle, white water lilies, and garden lettuce. All of these would bloom between five and seven in the morning. That’s about as far as he had gotten with the clock. Aphids collected on the cerulean morning glory blooms. The tiny pests oozed clear pellets of shit all along the petals and stems. Luckily, Ella was prepared to fight the buggers, a common summertime pest in their garden. She’d ordered a batch of butterfly larvae from her university entomology department. Madeleinea lolita, a natural enemy of aphids. The species’ blue hue matched that of morning glories, its name drawn from its discoverer, Nabokov. Ella had reread Lolita a dozen times last year. It was assigned in her sophomore literature elective, Monomania in Modern Literature.

Ella slipped on a pair of latex gloves and removed the larvae from a brown paper bag. She planted the tiny sleeping nuggets into the ground, as a small prayer. One day, they would metamorphose, escape into the world as something altogether different. They would eat away at the pests that plagued the nascent blossoms. Ella covered the larvae with topsoil, and mixed in some green clover manure. It seemed fitting: The garden clock was a disheartening example of letting an idea turn to shit. Ella packed the earth with her hands. Night gardening made her feel light and heavy, all at once. She was sick of sleeping when everyone worked, lived, loved.

The full moon struck whitish flowers with an eerie beauty. Night blooms—that’s what Ella would plant. She fetched seeds from the vault and set them down in dirt, wondering if they resembled the packet pictures. She planted evening primrose, night phlox, and the paper white moonflowers: night-blooming cereus, flowering tobacco, Datura inoxia. Jasmine, Anwar’s favorite, lined their fence, far enough away to not compete. On each packet was a file tab sticker tagged with Anwar’s loopy handwriting, notes on each variety:

Datura inoxia. Sacred to the Aztecs (toloatzin),

Smoke leaves and flowers for asthma (Ayurveda).

Chosen hallucinogen of thuggees.

All parts are poison.

The mash of lentils and soil and cucumber peel flooded her nostrils, and she removed the gloves to feel the earthy mixture ooze between her fingers. She gave the seedlings a gentle hosing and flushed her hands clean of muck. In her sweaty white T-shirt, Ella lay on the hammock and swung from side to side to make a breeze. Her brain refused to turn off, afraid that the stillness would encourage forbidden thoughts.

She pulled her father’s glasses from her jeans pocket It was silly, wearing these. She’d bought new copycat frames—tinted gray aviators—with her prescription, since his overcorrected her vision. But she soon realized that wearing Rezwan’s frames provoked her hallucinations. This had happened half a dozen times since Ella’s makeover. She thought about how Charu had embraced her, teary-eyed, with an ecstatic “Now we have to go shopping, El!” And true to her word, Charu bought her tailored slacks and shirts from Fulton Mall, and even made her a shirt based on one of their purchases. Ella hadn’t even gone with her, but all the clothes fit perfectly.

Ella looked at the garden, everything heightened by her father’s glasses. Four Benadryls, or sleeping candy, as Charu called it, didn’t work. She yearned for company, for someone to talk to, but there was no one she could think to call.

A beeping sound came from her bedroom window. She switched back to her own glasses and went to investigate.

She slid open the door and tiptoed through the kitchen and living room, trying not to creak the floorboards. She went into her bedroom. The alarm clock read quarter past six. The beeping had stopped. She cracked her bedroom door open and saw Maya whispering her prayers, knelt in prostration. Remarkable, how Maya set her alarm for so early. As Ella took a step backward, she heard:

“Ella?”

“Don’t let me interrupt you.”

“No, wait. I’m almost done. This is the part you ask for stuff.”

Ella waited for her to finish. After a few more whispery requests, Maya turned her head to the left, then the right, then clasped her hands once more. As she rose up her knees popped like bubble wrap, and she laughed.

“Eighteen going on eighty,” said Maya.

“I’m going back outside.”

“Came I come?”

“Uh…”

“I’ll take that as a yes.”

From Bright Lines: A Novel by Tanwi Nandini Islam, published on August 11, 2015 by Penguin Books, an imprint of Penguin Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House LLC. Copyright by Tanwi Nandini Islam, 2015.

A Short Q&A with Tanwi Nandini Islam

question by Nadia Q. Ahmad

Is writing like gardening? If so, how?

The act of writing is like gardening, in that each seed you plant, you must till and nurture until its rightful end. But what I’m interested in is where we must let the inevitable magic take its course, everything we want to write reveals itself to us at the right time. My mentor at VONA, Jeffery Renard Allen, called it serendipity, and that has stayed with me. The moment we plant the seed, we’re counting on all the serendipitous moments that will let it come to fruition, let it live out its destiny. And I try to have that attitude towards writing, research and revision.

Anwar’s and Ella’s garden is not only as a setting, but also a character, and a metaphor. What has using the garden/gardening in this way helped you explore?

I wanted to connect primordial bonds, and how they can be understood through the primordial metaphor of the garden. The garden is a way for the characters to explore bonds within the family, with lovers and faith. The Saleem’s gardens lets the family connect to trauma – Anwar’s PTSD from the Bangladesh Liberation War, and Ella’s loss of her parents. I wanted it to feel like a sanctuary at the beginning of the novel. However, there’s a shift, when the garden turns dangerous, and that marks a shift between the characters and their relationship to each other. Its beauty and the patterns the family has built around the gardens existence must be destroyed to see what they have lost. Their garden marks the passage of time, like a heartbeat throughout the novel.

Do you have a favorite flower / scent? Does it change depending on where you are?

Hibiscus produces a musky, earthy ambrette oil, from its seeds. Champaca flowers are deeply fragrant and remind me of summertime in South Asia. Sandalwood, from trees is my ultimate essential oil. Mysore Sandalwood is endangered, so I’ve gotten into Royal Hawaiian Sandalwood that has its distinct aroma and is sustainably harvested.

At this point in the novel, Ella and Maya have just met; this is one of the first scenes in which we see them get to know each other without Charu around. Ella’s aunt Hashi has also just given her a makeover in her home beauty parlor: she cuts Ella’s hair “short, like a boy’s,” and we find out that she has been saving her brother Rezwan’s (Ella’s father) clothes for Ella to wear. What do you think Ella’s character––and the way others react to her––offers to the ways in which we think about Asian American, and even Bangladeshi American, literature and identity?

Ella’s a character who is undergoing massive changes – physically, emotionally – and I wanted to write parents who simply accept Ella’s masculine presentation. Her adoptive parents attribute Ella’s gender identity as her inheritance from her late father – his gait, his height, his voice. Rather than a blatant coming out, there’s a subtle acceptance that lets Ella come into her own. In this scene with Maya, the tension is less with Ella’s gender identity, than with Ella’s burgeoning desire. That’s much more interesting to me.