There is always a risk of misunderstanding in all kinds of conversations, but those risks are more acutely felt in translation, and even more acutely felt in translation that calls forth past and ongoing traumas.

October 14, 2020

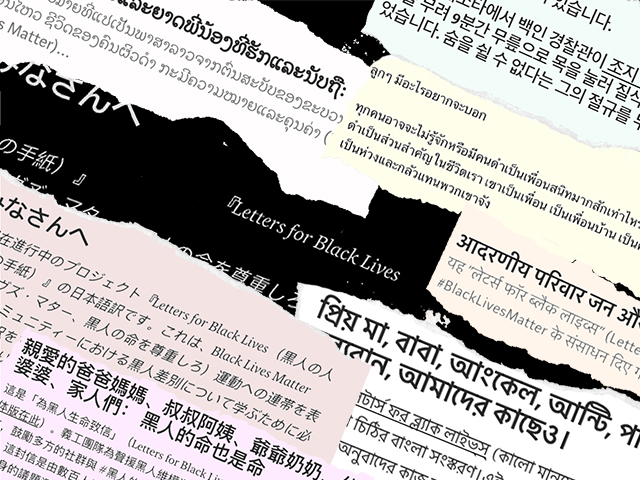

In June of this year, weeks after George Floyd and Breonna Taylor were murdered by the police and uprisings in defense of Black lives spread across the globe, a group of 330 translators assembled on Slack to confront anti-Blackness in their communities. They set off to collectively rewrite and translate a letter, which itself was composed by over 1,500 contributors, to their families and friends—a letter to urge them not to stay silent in the face of white supremacy.

The translators for the 2020 Letters for Black Lives project were located all across the world, and the languages they translated letters into ranged from Albanian, Bangla, and Burmese to Khmer, Nepali, and Tagalog, among many others.

This year’s collective epistolary effort grew out of the 2016 Letters for Black Lives project, which was a response within the Asian American community to the murder of Philando Castile in Minnesota. Addressing why they felt a need to revisit and translate new letters, the collective wrote:

Since then we’ve had four years of increased racism within the US and another rise of white supremacy around the world… we are now moving into the fifth month of a global pandemic where Black and Indigenous communities—which have historically been underserved—are disproportionately affected by the lack of healthcare and other social resources. And then an Asian American police officer stood guard while George Floyd was murdered by a cop… And so more people showed up, the context changed, and people were angrier, so the community wrote another letter because we cannot stay quiet while those in our community literally stand for white supremacy.

When we came upon the 2020 Letters for Black Lives Project this summer, we were taken by the energy, skill, and care of the collective translators. The architecture of the Slack interface—broken up into countless language-specific channels as well as into channels for outreach and regional conversations—was an expression of the collective spirit of the whole endeavor. There was no one spokesperson and instead many sets of hands shaping pathways for conversation.

It was clear that the project was rooted in an attempt to converse, recognizing that the need for sensitivity and care is counterbalanced by the urgency of the message: Black Lives Matter. As we began to read the final letters on the project site, we wondered what they might obscure—what conversations and questions, an inevitable outgrowth of any translation project, were not visible to us. And so we reached out to the collective via Slack and asked them if they would contribute micro-translators’ notes for the letters they translated. We wanted their help in making visible the difficult conversations along the way to difficult conversations. We asked about motivations for getting involved, phrases that dramatically changed between drafts or that were focal points of debate, and more generally a sense for the conversations that took place on the margins of the google docs page, in comment bubbles that eventually floated away once resolved.

Translators wrote about the influence of cultural histories in selecting entry points to the letter, the careful choice of pronouns in imagining a readership, and the many ways to translate the phrase “Black Lives Matter.”

What we’ve tried to do below is mimic a conversation in a room by publishing all the notes as a chorus. The reason for that is tied to the collective spirit of Letters for Black Lives, not only in the writing and translation of the letters, but also in the larger goal of the project—to kickstart a conversation with family and community members who aren’t so easy to talk with about racial justice and anti-Blackness. There is always a risk of misunderstanding in all kinds of conversations, but those risks are more acutely felt in translation, and even more acutely felt in translation that calls forth past and ongoing traumas.

—AAWW editors

Head over to AAWW Radio to listen to our repost of the Letters for Black Lives episode of Asian Americana, a podcast hosted and produced by Quincy Surasmith that further explores these conversations about writing and translating the Letters for Black Lives

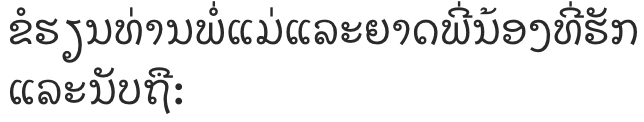

Saengmany Ratsabout on the Lao translation:

I live in the Twin Cities in Minnesota, on land stolen from the Dakota people. Minnesota, a place that rose into the national spotlight for the atrocity and killing of Philando Castile (July 6, 2016) and George Floyd (May 25, 2020) by police officers. The years and months since these killings have taught us about the deep solidarity work among Indigenous, Black, Asian, Latinx, immigrant, and refugee communities. From the uprisings and civil disobedience to the Letters for Black Lives project, individually and collectively, we find our voices and paths to express our sadness and anger towards the systemic killings of Black lives.

Collectively, members of the Lao diaspora came together and formed the Lao translation team for the Letters for Black Lives project. The project is particularly important as the Lao community begins to heal our wounds and historical trauma while marking the 45th anniversary of resettlement in the United States.

The translation team’s goal is to begin having conversations in the Lao community and address anti-Blackness, particularly societal views and perceptions of Blackness. Translation work requires the knowledge of both language and culture and often calls for descriptive words for terminologies that might not hold the same meaning when translated. The translation team had substantial conversations on how to translate Black Lives Matter, particularly the word Black. We wanted to acknowledge the presence of colorism in Lao society. Blackness or people with dark complexion are perceived as individuals who are unacculturated and those who live outside the margins of modern society. Given this awareness of Blackness, we decided to use the descriptive words, ຄົນຜິວດຳ (person with dark complexion) as opposed to ຄົນດຳ (Black people). In doing so, we intended to invoke the marginality and discriminative lived experiences that members of the Lao diaspora may have personally encountered. Secondly, we wanted to begin conversations about unconscious biases and discrimination toward Black people in our community and broader American society.

For the Lao community, these conversations with our parents and elders will be a difficult one. On top of the institutionalized racism and anti-Blackness embedded upon refugee communities as they are resettled into poor and urban areas by the U.S. government’s problematic refugee dispersal policies, the concept of social movements and uprising may reignite historical trauma for our elders. It was not too long ago that our elders lived under French colonialism, Japanese occupation during World War Two, experienced the civil war in Laos, and witnessed the abolishing of a centuries-old monarchy. Laos’ civil war divided families and neighbors into factions, each promising freedom and better livelihood for the mostly rural populace. Our parents and elders knew firsthand what happened when people rose up to authorities, government, and factions with competing promises. They became victims of war and empire-building, uprooted from their homes, and settled on stolen land to compete with disenfranchised Black people and other minorities.

Although we live in a challenging time, and the road ahead will be difficult, the seed of change begins with voices and stories. It is the voices and messages of solidarity for Black lives, whether through social media posts, protesting, or donating money and time. We learn best from each other and rely on stories to inspire us. Let us be committed to sharing the stories of Black lives and why we love and support our neighbors, friends, and family.

Mi Hyun Yoon on the Korean translation:

The 2020 version of the Korean letter differs both from the 2020 English standard letter and the 2016 version of the Korean translation by making references to the 1992 LA uprising. We felt the need to address the proverbial elephant in the room as the media’s focus on looting and violence by some protestors would detract from the main message of the letter and the movement. We knew that the memories of stores and businesses in Koreatown burnt to the ground and looted by Black people still rang fresh to many of the older generation so we emphasized why peaceful protests had no choice but to escalate.

We also emphasized and drew connections to South Korea’s own history of resistance against violence and oppression to establish democracy. It was writing this section of the letter that drew most debate among the translators because we wanted to balance the historical account of this period without turning off certain older members of the Korean American community who had conservative political views. We did not want those who deny the democratic protests at Gwangju and support the release of former President Park Geun-hye from prison to have any reason to ignore the message of the letter for the assumed political skew on the South Korean side that the letter could be perceived to have. By my suggestion, the letter also avoids normalizing “Korea” as South Korea by being intentional when this term is used.

Bedatri D. Chodury on the Hindi and Bengali translations:

I grew up in Calcutta, India to a mother who is nicknamed Krishna, after the blue-bodied/dark Hindu god. Some of her friends even call her Kali, after the dark-skinned Hindu goddess, to this day. In India, fairness creams are a $23 billion industry. My skin is dark, like my mother’s. As I now come to realize, the girls who stood in the center of my childhood dance dramas, the girls who played the protagonists in school plays, all had much lighter skin than me. Although most Indians believe that skin color bias in the country is a result of British colonialism, it actually traces back to the upper caste, Brahminical idea of equating purity and fairness of skin.

My motivation for joining the Hindi and Bengali translation projects for Letter for Black Lives was primarily to tug at the facade that South Asian communities hide behind; a facade that says that racism is an American problem and that Black Lives Matter…only in America.

When translating the original template, we decided to add South Asian examples of allyship to drive home the interconnectedness of our struggles; we harked back to how our “legal” immigration to this country stands on the shoulders of the civil rights movement. We spoke of Ambedkar, Gandhi, Kamaladevi Chattopadhyay, who were inspired by the Black struggle for racial equity.

The Bengali word kalo means black, and dark-skinned people are often called krishnango—people whose bodies are coloured like Krishna’s. We decided to not use the latter because of its rootedness in Hindu mythology. The words for black in our languages only refer to the color. It is hard to encapsulate a whole race, webs of histories, and a movement towards justice in a word that signifies a color and not a race. However, it allows us to look beyond racial limitations to Blackness and pushes us to question ourselves on how, beyond the United States, we negotiate with our biases against people whose skin colors may or may not be black.

Agnes Oshiro オオシロ アグネス, Akané Kominami 小南 茜, Kione Kochi 赤尾 木織音, and Setsuko Yokoyama 横山 説子 on the Japanese translation:

In translating “Black Lives Matter,” the foremost goal of the Japanese translation team was to faithfully represent the mission of the Black Lives Matter movement—“to eradicate white supremacy and build local power to intervene in violence inflicted on Black communities by the state and vigilantes”—while providing appropriate cultural context for our intended audiences. In particular, it was critical to emphasize the movement’s emotional and political urgency to our readers for whom the concept of Black Lives Matter may be foreign, seemingly irrelevant, or otherwise difficult to empathize with.

Upon revising the translation「黒人の人達の命を大切に (Treat Black Lives with Respect)」used in the 2016 letter with a renewed sense of gravity, the 2020 translation team considered more than fifteen versions including 「黒人の命はかけがえない (Black Lives Are Irreplaceable)」and「黒人の命を軽んじるな (Do Not Neglect Black Lives)」. Both of these options presented unique challenges, including the implications of using a particular tone, and concerns for connotations beyond the translators’ control. For some,「かけがえない」amplified the inalienability of Black lives while others found the expression to be too passive. On the other hand, 「軽んじるな」embodied the rallying cry for social justice, but the combined effect of the word choice (“neglect”) and the negative sentence structure seemed to detract from Black power, rather than building it up. The team ultimately chose 「黒人の命を尊重しろ (Respect Black Lives)」with the verb in the imperative form, which demands attention to the historical inequity bolstered and sustained by systemic racism and aims to mobilize non-Black communities to dismantle white supremacy in every nook of our society in solidarity with Black communities.

Kelsey Owyang on the Chinese translation:

Black Lives Matter.

This statement derives impact from its brevity. It centers Blackness. It even avoids, or perhaps addresses head-on, the issue of whether “Black” should be capitalized or not by placing Black lives at the top of the sentence. It is a pithy and powerful rallying cry.

In Chinese, the most common translation of this phrase is 黑人的命也是命 (Hēirén de mìng yěshì mìng), which can be re-translated into English as “Black lives are also lives.” It’s easy to feel that this translation is lacking. For starters, its wordiness makes it a weak partner to “Black Lives Matter.” Chinese translators working on the Letters for Black Lives project also argued that the phrase draws a false equivalency. One translator wrote, “What ‘Black lives are also lives’ does is bring the entity of the Black life DOWNWARDS toward an incorporation into universal livelihood… What ‘Black Lives Matter’ does is AMPLIFY the strength of Black Lives and in doing so Black Power. We need a much stronger sentiment to capture that amplification.”

The team proposed and debated at least thirteen options before choosing, through a vote, the revised phrase 黑人生命至关重要 (Hēirén shēngmìng zhì guān zhòngyào: “Black lives are extremely important,” or “Black lives are of the utmost importance”).

While the revised phrase seemed like an excellent mirror of the original English, it was voted out in the last round of edits. Writers raised concerns that it was too strong: would it turn our Chinese readers away from this conversation about Asian Americans’ role in the BLM movement? If so, could opening the door to the conversation—perhaps by providing a gentler translation of “Black Lives Matter”—be more valuable than not having the conversation at all?

Our final letter reverted to 黑人的命也是命 (Hēirén de mìng yěshì mìng), that gentler translation, but I still don’t know if this was the right answer. Translating a social movement across cultures is a task that does not lend itself to right answers. I only hope that the translators of this piece, though we may diverge in our syntactical opinions, can converge in our commitment to supporting racial justice movements and valuing Black lives.

Read a longer post about the BLM translation issue here.

Quincy Surasmith on the Thai translation:

How do we soften our language for our families when the message of supporting Black lives is so heavy?

In Thai, our relationships, our relative ages, and our status are all key to the language. The pronouns we pick to address ourselves and our reader can make all the difference in whether a letter seems like a formal editorial piece, a curt demand, or a loving, empathetic message. The subtle tonal shifts between I, we, your children, and we little ones navigate a wide field of intent and understanding.

In English, the letter speaks simply and directly. It is meant to both be easy to understand, and get straight to the issue at hand—that of supporting Black lives. But in Thai, we found ourselves going back and forth on how to refer to ourselves and to our readers. We also found ourselves debating on whether to add softening words to our sentences. “We need to talk” became “We children have something we’d like to tell you.” Transitions to discussions of unjust deaths had to be bridged with “so we think you’d like to see” and “if we could please bring your attention to.”

We went back and forth a ton on this, especially because in English, adding those softening terms feels like it takes away from the gravity of the issue, not to mention lengthening the letter. But the guiding principles of the letter encouraged us to be familiar, personal, and aim to guide instead of lecture. So ultimately, we kept in all the softer phrasing. It was more important that our communities take in the message, instead of merely receive it.

Chung-chieh Shan on the Chinese translation:

“We have been blamed for bringing poverty, disease, terrorism, and crime.”

This original English sentence comes in the middle of a paragraph in the 2020 English language letter. The paragraph is about how “I” am grateful to “you”; however, the family unit where “you” raised “me” is only a fraction of the societal “we” that “have been blamed.” The sentence also comes towards the end of a “narrative arc” that “moves gradually from talking about Black people closest to us, to talking about all Black people”; thus, the four remaining “we”s in the letter can include you, me, and everybody including all Black people.

For these reasons, the traditional Chinese translation states more specifically that “華人 have been blamed for bringing disease, poverty, and crime.” The meaning of the diasporic term 華人 flickers between those who think and talk like us, who we hope will make sense of our translated letter, and those who look and breathe like us, who have been racialized to be blamed for COVID-19. Our translation thus straddles an imagined community of Sinophones—we are driven to produce a single text in the traditional Chinese alphabet by print capitalism—and an interest-based community of the ethnic Chinese living in the United States. The simplified Chinese translation renders “we” as “我们亚裔人” (we Asians)—perhaps a different straddle.

These letters are mere resources for people to edit and use to start conversations, so even though I contributed to the translation, and even though I belong to the “we” and the “I” and the “you”, I might not ascribe the term 華人 to myself, a 1.5th-generation Taiwanese American. It makes me uneasy to call myself 華人 because the instability of the term’s meaning allows too much cooptation. A sharper way for me to locate myself in this diaspora would be for a stranger to ask me the Chinese equivalent of “where are you from?”—namely “你是中国人吗?” (Are you Chinese?)—so that I may answer in Mandarin “不是” (no).

Agnes Oshiro オオシロ アグネス, Akané Kominami 小南 茜, Kione Kochi 赤尾 木織音, and Setsuko Yokoyama 横山 説子 on the Simplified Japanese translation:

Having published the Japanese translation of the 2020 letter, the team also prepared a simplified version so that the text could be useful in K-12 classroom settings or for those who are not as familiar with the form of writing used in the initial translation. For example, “anti-Blackness” translated as「反黒人主義」in the original letter was replaced with a more descriptive「黒人の人たちを下に見る仕組み (social structures that look down on Black people)」.

In addition to unpacking the concept, we also identified difficult Chinese characters that could be replaced or supplemented with Japanese phonetics to facilitate ease of reading, such as「闘い」for “the struggle.” Faced with the limited affordance of our online platform Medium, we published one version with the pronunciation in parentheses following the characters—e.g.「闘い」(たたかい)—and a PDF version with ruby text on top of the characters to annotate their pronunciation. While these examples illustrate what translators opted in, there were also decisions we consciously opted out of. For instance, in an effort to succinctly describe the term “racial justice,” we initially decided to represent it as「人種的正義」and to gloss it with sociohistorical context in parentheses (過去の人種差別を認めて償い、公正な社会の仕組みをつくること, “to acknowledge and make amends for the harm done by racism and build a just social structure”) because the literal translation is not yet a part of the common lexicon in Japanese.

While the translation was accurate, it quickly dawned on many of us that if we fixated on word-for-word translation of a difficult concept we might risk alienating the readers of this simplified version. After much deliberation, we as a team decided to incorporate the call for social justice and the need for reparation for racial discrimination throughout the letter. Lastly, for the letter’s title we chose “Simplified” Japanese with the appropriate characters「易しい」to avoid possible confusion with its homonym meaning “Benevolent”「やさしい / 優しい」. Because the Japanese language was weaponized against peoples of South, Southeast, and East Asian communities under the rule of Imperial Japan, we strove for an anti-imperialist translation practice in line with the principles set by the Black Lives Matter movement leaders.