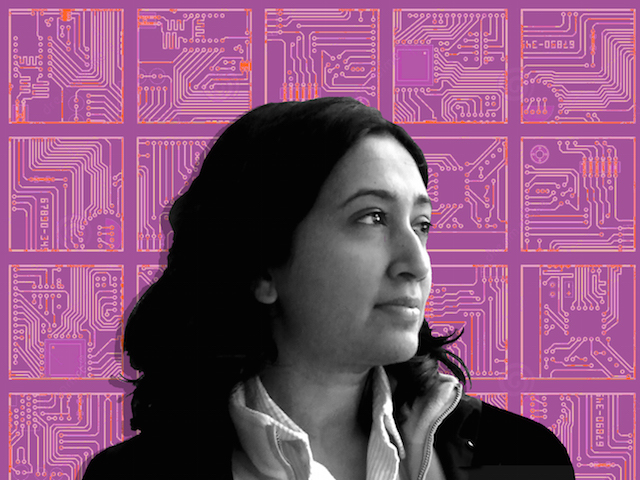

The Indonesian fiction writer Intan Paramaditha on the political potential of horror and writing as a feminist practice

December 10, 2015

Intan Paramaditha published her first short story collection, Sihir Perempuan (Black Magic Woman), at the age of 25. That same year, she left Indonesia to go to graduate school in the United States, where she has spent most of the past decade. “I have been away from Indonesia for so long that it is hard for me to say that I only have one home,” she writes.

As a fiction writer and scholar whose work explores where gender and sexuality, culture, and politics meet, her creative and scholarly pursuits have informed her political views and aesthetic preferences. In practice, however, the worlds she shuttles between are not always connected: “I often feel like I am living two separate lives, in two separate spaces—emotionally, linguistically, and geographically.”

The following interview with Paramaditha was first published in the anthology Indonesian Women Writers edited by Yvonne Michalik and Melani Budianta, recently published by Regiospectra.

Read her short story “Apple and Knife” in The Margins.

What made you choose to express yourself through fiction?

In elementary school I started writing stories using my mother’s typewriter, and she supplied me with so many books, from Grimm and Hans Christian Andersen to Agatha Christie. She bought a computer when I was in the fifth grade. And because both my parents worked, I had the computer just for myself during the day. That’s when I started experimenting with writing. When I was eleven, my first short story was published by Bobo, a popular magazine for children at that time.

I continued writing stories throughout my teenage years, but I kept them just for myself. They were simply terrible. It was only after I graduated from college that I thought more seriously about publishing. In 2004, I began to send my stories to major national newspapers, and I started to get to know some literary circles. I published my short story collection, Sihir Perempuan, in 2005, a few months before I left Indonesia.

I do not recall having made a fully conscious decision to express myself through fiction. I grew up reading, writing, and listening to stories. I am fascinated not only by what is revealed but also what is hidden. Stories are structured to tease, to manipulate. The ongoing question for me is what stories to tell and how.

Did you get support from your family to become a writer?

I have never made an official ‘decision’ to be a writer. After graduation I worked as a lecturer at the University of Indonesia, and that was the time when I started publishing fiction in the media. My father, who wanted me to work in a major corporation (just like he did), was not very happy about the university job because I did not make much money. It was not the profession that troubled him, though, because he thought that being an academic was a respectable position. Perhaps it would have been different if I had become a full-time writer.

My mother supported everything that I do, but my relationship with my father was not easy. My time as a college student was filled with personal problems. Those were difficult moments for my family, and I fought a lot with my father. I saw him as an oppressive figure and, being young and naïve, I became angry, rebellious, and withdrawn. Around that time I learned about feminist theories, and perhaps – as happened to many others – my feminist politics began with the personal. I started to pose questions on the larger discourses that have produced someone like my father. Now that both of us have grown older, I have become more forgiving.

How would you describe the status of women in Indonesian society? Do you see any changes since Suharto’s fall in 1998?

It’s hard to make a generalization about Indonesia due to its size and diversity. The politics of decentralization after the fall of Suharto makes it even more difficult to contain frictions and discrepancies. There are more women in the cabinet in President Jokowi’s administration, but discrimination against women’s bodies and sexuality at the policy and cultural levels is still very strong. Women’s sexuality is policed (this is an ironic use of the word ‘police’ since Indonesia forces its female police to do a virginity test, which is very degrading). It is constantly deployed to assert political power, as one could see in the cases of discrimination and violence against women by authorities in the sharia-enforced province of Aceh.

On the less frustrating side, women activists, artists, and scholars are more visible, and they largely contribute in circulating gender and sexuality issues in public discourses. In post- authoritarian Indonesia, however, everything is visible. So on the one hand we have women ceaselessly protesting discriminatory laws such as the 2008 Pornography Law, and on the other hand we also have vigilante groups who demonize women’s sexuality. It’s a fierce visibility contest. And the challenge for women activists is to constantly explore new modes of articulation for gender and sexuality issues in order to expand their public.

Who and what inspire you the most? Do you have any literary models?

My early works were inspired by women writers whose works could be considered ‘gothic,’ such as Mary Shelley, Margaret Atwood, and Anne Sexton. I read Poe, Stoker, O Henry, Guy de Maupassant, and Roald Dahl in high school, and I think their traces are all over my fiction. I learned a lot about characterization and narrative structure from Shakespeare – and also plays by Eugene O’Neill and Tennessee Williams. The two Indonesian works that influenced me the most in terms of tone, mood, and character are Malam Jahanam (Night of the Accursed), a play by Motinggo Boesye, and Orang-orang Bloomington (The People of Bloomington), a collection of short stories by Budi Darma. There are so many literary models that I have not mentioned, but in general I am drawn to the combination of a dark quality in the story (e.g. a dark atmosphere or state of mind) and subtlety in storytelling.

How would you describe your creative process? Do you need a specific environment in order to write?

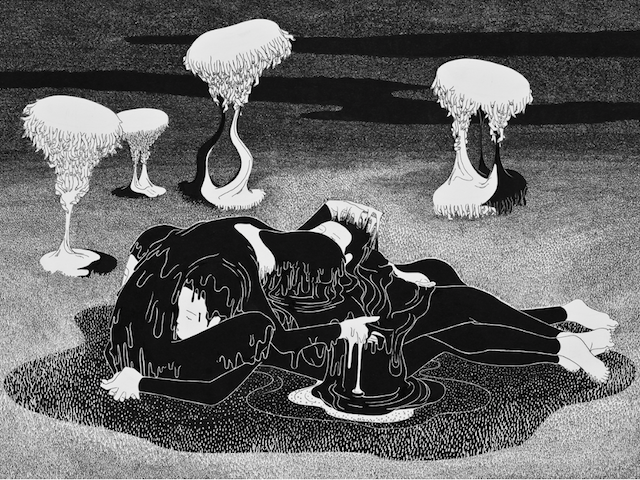

I am interested in strong visual images, and I love creating stories to frame, twist, and recontextualize those images. I am a slave to narrative. I grew up with it. For instance, the Quranic/Biblical story of Yusuf/Joseph lingers in my mind because I am fascinated by the image of women cutting their flesh instead of apples as they see a very beautiful man in front of them. I created the short story “Apple and Knife” to provide a new narrative to reframe the image.

And yes, I do need a specific environment to write. People always thought I’d stay up late, working under a dim light, to find inspiration for all those dark stories. Contrary to the expectation, I am a morning person. My ideal time for writing is between 7 and 11 am.

How do you feel about the reaction of the Indonesian people towards your writings?

When I published my short story collection, back in 2005, people in the literary scene were quite busy understanding and categorizing the new generation that emerged after the 1998 Reformasi. They were preoccupied with labels. People put me in the category of “women writers” and they added more specific tags, such as “women writers who do not focus on sex” (unlike Ayu Utami, Djenar Maesa Ayu, etc) or “horror with a feminist twist”. These labels are productive, but sometimes they are confining. I am very concerned with sexual politics, so sexuality is always a part of my writing. Most of my stories are not sexually explicit, but some others require a different writing strategy. And there’s the horror label. Some readers find it hard to accept my works that do not belong to this category. All of my stories are dark, but they are not necessarily horror. I think categorization is helpful as long as it allows for more fluidity and revision.

In recent years, there have been more and more writers in Indonesia’s publishing industry. They talk about labels in a different way, that is, as a “brand”. To me, “author’s brand” sounds like a phrase from another planet. The most important thing for me is to know what I want to tell, why it needs to be told, and what narrative tools are best to serve the story.

You are known for developing your own narrative style, one which fuses the genre of horror with a feminist voice. Can you tell us about your aesthetic exploration? Why and how did you come up with this style?

I became interested in the potentials of horror when I wrote an undergraduate thesis on Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein and Percy Bysshe Shelley’s Prometheus Unbound. I viewed Frankenstein as a feminist novel that challenged the gender ideology of 18th century British Romanticism. I concluded that writing should be a feminist practice. And Frankenstein is a horror novel – in the popular gaze the genre seems harmless (many people are not aware that Frankenstein is the doctor, not the monster), but if you look at it more deeply you will know that it is subversive. I guess for me that was the initial attraction to the horror genre.

My second short story collection, Kumpulan Budak Setan (The Devil’s Slaves Club, 2010), which I co-wrote with Eka Kurniawan and Ugoran Prasad, is an exploration of horror in the local context. It is a rereading of works by the most prolific Indonesian horror writer Abdullah Harahap, whose name was quite forgotten when we began our project in 2008. Horror in his writings is a site to talk about the tension between the urban and the rural space, the disillusionment with developmentalism (in the 1970s-1980s), and the control and absence of the state. I expand these issues in my stories, framed with a feminist perspective.

Currently I am becoming more and more interested in the themes of travel, cosmopolitanism, and globalization. Sometimes horror works, but sometimes it doesn’t. In my last short story, “Klub Solidaritas Suami Hilang” (“The Solidarity Club of the Missing Husbands”), I move away from the elements of horror (though not completely). I think the most important thing is to serve the narrative. The aesthetic style comes later, as a strategy by which you choose to tell the story.

I often get questions like “Do you believe in ghosts?” or “Have you ever experienced an uncanny event?” and I make people disappointed by answering “No” (apparently my own personal experience is not that fun!). What intrigues me about ghost stories is the cultural meaning that they produce. When I was a child, I had a female Quran teacher who told me this legend in her hometown about a female ghost who licks menstrual blood in the bathroom. I never forgot how grisly the story was. When I grew older, I learned about the cultural anxieties about women’s bodies and sexuality in society, and I immediately thought of that story. The visual image and the way that it came to me via my Quran teacher disturbed me. I ended up incorporating the bathroom ghost and my teacher in one of my early short stories.

Collaborating with a female director, Naomi Srikandi, you have adapted one of your short stories, “Goyang Penasaran “ (“The Obsessive Twist”) into a play in which a transgender character replaces the female protagonist in the story. Tell us the reason for your experiments and what you want to achieve through your adaptation. Who was your target audience? Do you think you succeeded in achieving your goal?

“Goyang Penasaran” (“The Obsessive Twist”) reworks the story of Salome in the context of the rise of religious conservatism in post-Suharto Indonesia. It is about a beautiful dangdut singer/ performer, Salimah, who is banned from performing in her village after a religious leader announces that her dance movement provokes zina of the eyes (zina in Islam is fornication or adultery). Two years later, Salimah returns as a strange woman, wearing a veil and looking deadly, and takes revenge. In the theatre version, a male actor cross- dresses as Salimah. So she is not a transgendered character. Rather, the audiences are expected to accept – within the conventions of the play – that the male body on stage is a sexy dangdut performer. We decided to do this as an experiment with the ways of looking. What is the relationship between the audience and Salimah as they see her on stage? Would they challenge or reproduce the ways in which male characters objectify her body?

The play was performed at the Teater Garasi studio in Yogyakarta and Salihara Theatre in Jakarta. With regards to the medium and the space, Goyang Penasaran had a very limited audience: the urban middle-class. Our goal was to provoke questions around the gaze and the eroticized body of a dangdut performer, how we look, and the relations between religion and the performance of piety. The performances were successful in expanding the theatre-going public (many of the audiences at the Salihara were not regular theatre- goers). However, there was a real challenge in how to expand the public beyond the confines of the urban middle-class.

Besides being a fiction writer, you are also a lecturer, researcher, scholar, and a cultural activist. How are your other activities related to your career as a fiction writer?

The themes in my stories are very much informed by my scholarly readings. The short story-turned-play Goyang Penasaran, for instance, was influenced by my own academic interests in the relationship between sexuality, politics, and religion in Indonesia today. On the other hand, my fiction writing style has enriched my academic writing, so I thought a lot about narrative, tone, and rhythm when I wrote my dissertation.

About the activism – it’s mostly related to my interests in gender and sexuality as well as my scholarly research on film and media. I was, for instance, involved in the advocacy against the 2009 Film Law. I think I am just like everyone else of the 1998 generation, who witnessed the student movement and the fall of Suharto. We are all culturally constructed to contribute something, however small, towards activism.