Jennifer Kwon Dobbs, inquiring into a poetics emerging from the adopted diasporic condition, guest-curates a portfolio of poems for The Line Break.

July 5, 2013

Although readers may be tempted to file this collection under “adoptee writing,” they might instead take notice of how these aesthetically diverse poems enact an urgent poetics emerging from displacement by war, militarism, poverty, social stigma against single mothers, neoliberal outsourcing of social welfare, and cultural and linguistic loss. In the not-so-distant past, to write from these conditions of orphaning would have been tantamount to expressing ingratitude, but today, to do so is to lay claim to history and to summon artistic and communal relatives for a poet’s task.

The poets in this portfolio are epic in sweep yet lyrically intense in contingencies of feeling and knowing. Their work recalls Myung Mi Kim’s definition of poetics as “that activity tending the speculative.” Yet unlike the witness who remembers history or who can turn to birth family or ethnic community to ask, the poet writing from an adopted diasporic condition oftentimes cannot testify to the events that orphaned her or him. These conditions retain an uncanny presence in her/his dream life.

Out of necessity, this poet speculates and stages as a way to make sense of haunting absences, divided geographies, socially deadened filiations, lost or sealed documents, bodies used by and buried under post-Cold War economic boom/bust:

The children, recorded, a homestead of lung and eye

—Sun Yung Shin, “[Orphanotrophia]”

Museums of burials, the underground of giving birth to birth

The poet reconstructs a site of orphaning as a site of crucial encounter and naming:

To shield you from the bullets stilling hanging in the sky.

—Kevin Minh Allen, “When Home Is Not Enough”

I’ve mastered the silence of your existence,

but now I shout your name in this dark cave.

Wherefore all this memory work? In Bryan Thao Worra’s “Songkran Niyomsane’s Forensic Medicine Museum, 2003,” birth family are released from administrative processing and revivified in a way that’s only possible in a poem:

I wondered if my mother, making her way across

The Mekong for a new life, might have found herself here

Tucked in a drawer anonymously among these samples

Of flesh, these cold cases in a tropical nation.

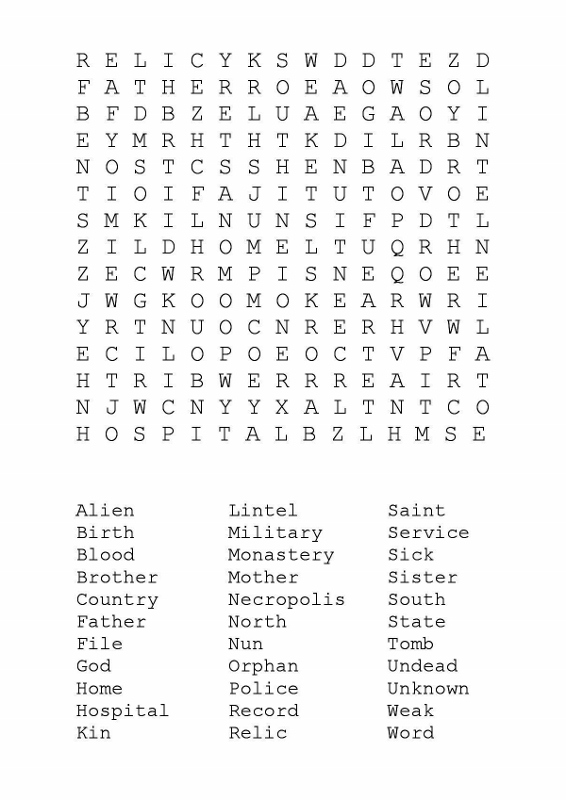

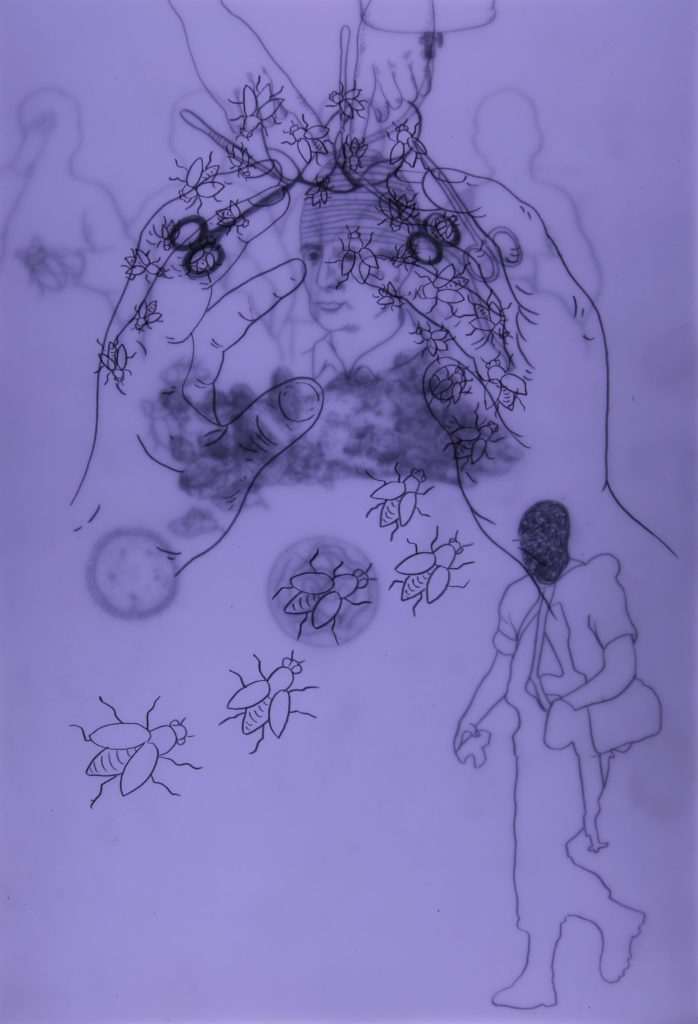

While editing this portfolio, I looked for work aware of its adopted diasporic condition yet committed to the task of making a poem. Whether speculating, searching, dismantling, reunifying, or something else altogether, language that seemed transcribed “at the interstices of the abbreviated,” as Kim writes, “the oddly conjoined, the amalgamated—recognizing that language occurs under continual construction” attracted me the most. At the same time, I sought to diversify this issue, keeping in mind that a fully representative cross-section wasn’t possible given space limitations. Working within these constraints, I also solicited artwork to punctuate the issue and to invite dialogue among the poems.

This portfolio might be considered a meeting place to reconcile Cold War histories and legacies from which an adopted person is amputated and estranged. In this way, the poems are both intimate and political by virtue of their restless insistence on wholeness and peace. I’m reminded of Muriel Rukeyser’s Life of Poetry: “Until the peace makes its people, its forests, and its living cities; in that burning central life, and wherever we live, there is the place for poetry.”

And in this place, we shall make another peace:

She goes to the window, opening

—Nicky Sa-eun Schildkraut, “a modern ghost family”

it to a crack, to feel the salty wind

against her face, to feel

the beginnings of danger.

—Jennifer Kwon Dobbs

1. “When Home Is Not Enough” by Kevin Minh Allen

2. “[Orphanotrophia]” and ”[Tumuli]” by Sun Yung Shin

3. “Untitled” and “14.5833° N, 121.0000° E” by Lisa Marie Rollins

4. “How to Divide a Peninsula” and “No Gun Ri, or The Battle That Wasn’t“ by Katie Hae Leo

5. “a modern ghost family” by Nicky Sa-eun Schildkraut

6. “Songkran Niyomsane’s Forensic Medicine Museum, 2003” by Bryan Thao Worra

7. “Fruit“ and ”Dear Satomi Shirai” by Molly Gaudry

8. “Gardening Secrets of the Dead” Lee Herrick

When Home Is Not Enough

by Kevin Minh Allen

Shrouded in rumor, your secrets were unraveling,

and the swelling underneath your blouse

was no longer a question of if but when.

Away you were sent to lie in a bed of lice and dried shrimp

in a village hostile to yet another bastard

who will end up begging for forgiveness.

But, here I am, back from the deep well they tried to drown me in.

To disarm the landmines buried in your field of vision.

To shield you from the bullets still hanging in the sky.

I’ve mastered the silence of your existence,

but now I shout your name in this dark cave.

And, if you never answer me?

Have you moved onto another village, another family?

What if it’s true when they say

that mosquitoes only return to the swarm

in the form of a warm memory,

however indecipherable?

[Orphanotrophia]

by Sun Yung Shin

A broad black market

The women are urnfields

The children are binding out

Dark in the trains, a burning mouth to eat a shovelful of black diamonds

Leak blood, trickle milk, time weeps

Going over the falls

Washing to shore, done and undone

Law-and-order, over the falls

Body paint, black ink and brush, state and subject

Eat silver and sugar

Tobacco hair and a hospital all in gold leaf

Baby Jesus in the alley, bright baby in a bullet

Time branching everywhere like hair

Custody this antebellum apprentice

Rows of graves—keep spilling the liquor

City of the dead, written from right to left

The women stand image and likeness

The women occur copy and heir

The children, recorded, a homestead of lung and eye

Museums of burials, the underground of giving birth to birth

[TUMULI]

by Sun Yung Shin

Untitled

by Lisa Marie Rollins

“Who claims this child?” James Cagney

Come on home, my dad says. He says it as if I am still 15, having run

away – again. As if coming home will make everything right, and

as if I am able to conjure up my 12 year old self. The self who

believes in his God the father, the one slowly seeing cracks in ‘if I

just pray hard enough’. If I just pray hard enough maybe I will

forget I am alien inside my own church walls, pews smelling like

mink oil, the bread of life stale and the wintry eyes of the assistant

pastor when he sees me during youth group.

14.5833° N, 121.0000° E

by Lisa Marie Rollins

“This Many Miles from Desire” – Lee Herrick

it is two thousand four hundred and six miles from Oakland to Molokai, Hawaii

six thousand nine hundred eighty five to Manila, Philippines,

somewhere in between and outside is where I look for you

for my face in photos you sent me

alongside photos I have stolen

from my sisters webpage

tiny mirrors on the wall

if I turn my head

just right

How to Divide a Peninsula

by Katie Hae Leo

Here is a table. It is a good table. We agree that this table must be spread, like all good tables. But what to spread it with? Here is a fine linen, here silk, here cotton, here a stiff wool. Each will share the beauty of this table. As a child I often sat under a table but never once thought about what the table wanted. Only legs and laps, only who owned them and what they meant to me. Such is the strange fate of tables. To exist only as we use them. Tables do not know what they want. Tables know heat and cold and the hands that touch them. They measure time in flakes of wood. If they could speak, their voices would be filled with dirt.

No Gun Ri, or The Battle That Wasn’t

by Katie Hae Leo

Four hundred porcelain cups lie broken in the sun. Who will take responsibility?

The policy regarding cups dictates that all cups must first apply to the Bureau of Ceramic Housewares for permission to assemble in open fields. This includes but is not limited to tea parties, picnics, family reunions, and outdoor banquets.

The official position on destruction of fine china is illustrated in a letter from the Ambassador of Dining to the Undersecretary of Kitchen Behavior. In this letter the ambassador worries that the extermination of unauthorized cups within the conflict zone might damage relations between tea drinking countries.

Remains of broken cups are still being discovered throughout the land. If cups had souls, they would roam the streets, unsatisfied.

Meanwhile, the Ministry of Collective Memory asks that all persons with knowledge of the cup incident report to their local branch, where they will be rewarded with a Starbucks gift card and a lifetime subscription to People magazine.

a modern ghost family

by Nicky Sa-eun Schildkraut

Act I.

In the film, a widower holds an audition

for a new wife. As each woman

steps into the closet, selecting a dress

for the rehearsal wedding, he sees

the right one, a young actress in simple

white cotton. There is no need to even

ask her name, or origin: she fits

inside each of his dreams of her

as a slight ballerina, a rising star

who fills his mouth with snow

on their wedding night, as he tells her

after she removes her simple

white cotton, “you are the only one

I will ever truly love.

Repeat after me: you are the only one

I will ever truly love.”

*

“It’s a post-war story, set in the backdrop of a city

rebuilding itself as a cosmotropolis.” The director explains,

“ Some of the war victims have undergone complete

facial transformations, surgical miracles,

in order to forget their former lives,

reinvent themselves. It’s an era of post-melancholia,

post-memory,” he pauses and lights a cigarette,

“there’s no longer any sense of the authentic,

or the individual. Everything is staged.”

*

“I wish I knew you,” the younger, second wife

touches the first wife’s face in the photograph.

“I’ve gotten so used to inheriting your odds-and-ends.”

Everyday, from the closet she slips on blue,

scuffed sandals and slip-dresses that fit

loosely around the waist. “If you were me, you

would laugh,” she says, laughing to hear

herself in the empty house, day after day.

She can smell the odd mixture

of jasmine perfume and cigarettes

seeped into the sleeves of the robe as she cleans

dishes, pantomiming the ghost-wife

as she fits her photograph inside a new silver frame.

“One day, I’ll be like you,” she whispers

to her, “immortal.”

*

The director writes another scene:

in flashback, with surreal, gray tones

like a dream sequence, the leading man

embraces his first wife in a boat with huge sails.

They look perfect, a movie-couple

beneath stars and full moon.

“I’ll never feel as lonely, again,” she says to him,

“as long as you stay here.” But the storm

above is gathering, a shock of black clouds

and relentless wind, as they escape inside

the cabin. She goes to the window, opening

it to a crack, to feel the salty wind

against her face, to feel

the beginnings of danger.

Act II.

The next day, the couple visits the studio

for another special audition. This time, second wife

is dressed in a yellow kimono, her hair upswept

in a messy bun. She enters the stage of the kitchen,

distraught, looking for something, her lines unclear,

clearly mad. From the front row, a small girl with a shaved

head gasps, pointing at her, “that’s her!” She runs

onstage, pulling the kimono off her shoulders,

exclaiming, “it’s her! I want her to be my

mother!” The director is laughing,

uncomfortably relieved now,

watching his distressed wife and this new,

grateful daughter embrace onstage.

*

According to the script: when the first wife

returns, not from the land of the dead, but

from the fully living, everyone is in shock.

It was a restful trip, she says, standing

in the living room that is no longer her color,

but painted over in blues.

Songkran Niyomsane’s Forensic Medicine Museum, 2003

by Bryan Thao Worra

Behind the Siriraj Hospital in Bangkok:

The Chinese cannibal’s corpse

Was stuffed and hung in a glass box.

His bad orthodontia flickers like nightlights

After hours.

Honestly, he’s a bad piece

Of shoe leather. Rancid jerky.

Impolitic students visiting the second floor

Contemplate Rama VIII as the Thai JFK.

Head doctors confirm

An uncommon number

Of unclaimed corpses

Received a single bullet

in the forehead

To study the methods

Of modern regicide.

Periwinkle tile and placid aquariums

Among imperfect babies soaking

Within dusty beakers of formaldehyde

Are supposed to soothe you on your tour.

A brown clay jar on the floor

Slowly fills with baht

For the solitary soul of a tiny boy

Crammed inside to suffocate by his last enemies

In the world.

Reach inside.

You’ll feel a young ghost’s hand

reach back, looking for toys.

I wondered if my mother, making her way across

The Mekong for a new life, might have found herself here

Tucked in a drawer anonymously among these samples

Of flesh, these cold cases in a tropical nation.

Behind you, Dr. Niyomsane’s own cadaver chuckles

From a clean hook, the eternal student, daring

Tomorrow’s professional investigators

to study him.

FRUIT

by Molly Gaudry

This white peach from the market down the street, its skin in my teeth and juice on my tongue, and how one bite takes me to that morning thunderstorm a decade ago exactly beneath which I met my biological father and later his wife, their daughter, their son, whose six-year-old body curled every night beside my eighteen-year-old anger on the living room floor where we all slept and where I stared into the lush green hills, choking back thoughts, searching those huge white cranes within that thick white morning fog for meaning, the incense burning its citronella spiral through the night. It wasn’t just peaches that summer but nectarines and plums and concord grapes whose skins and pits we piled up, and also green and white and yellow melons and fruit I’d never tasted, but I ate them because that was how we shared and spoke with one another—well, the fruit and the whiskey, the fruit and whiskey and cigarettes. Oh how we drank and how I poured with both hands as a sign of respect, and how that man said six-shots-in one well-past-midnight Monday do not ask me anymore about your mother and how his wife who was everything but the third-world woman I’d assumed all South Korean women were said me and put my hand beneath her breast, said omah, mother, bio-mom, okay and how I looked at her until she said again okay, you say, bio-mom and how I did not answer until days later when I watched her cut the evening fruit and reached and put the pieces in my mouth and when I swallowed said okay and how she shared a cigarette with me after everyone was asleep, and the way we looked out that morning and watched the cranes soar and listened to them cry, not saying anything but leaning, shoulder to shoulder, knowing it would never last, that I would return to America, that I would continue on with my life and so would she with hers. So what we did was eat. We ate that fruit all summer long.

Dear Satomi Shirai,

by Molly Gaudry

Dear Satomi Shirai,

My itch is not your itch, but I still recognize the signs of your transient life—futon, window unit, white unadorned walls, those awful plastic blinds. Do you even have a closet for your clothes?

My own clothes, my desk, my books, my shelves, are in a storage unit awaiting my return, alongside my dead grandmother’s couch and tables, her bed and dresser and nightstand. When I was very little, she used to introduce me like this: This is my granddaughter. She’s adopted.

Years ago, on Christmas Eve, I drank too much at dinner and protested when she wanted to go home early. It was snowing, the roads hadn’t been cleared, and I was tipsy. We got into the car anyway and I told myself to get her home fast, without getting pulled over. I don’t know why, but in the midst of that long drive through all that falling snow, I said, Want to see Grandpa? So we turned around and went in the other direction.

At the nursing home, I waited in the hallway while she went in to see him. They talked for a while and then Grandma said, I love you. Grandpa said, I love you, too. Good bye, Grandma said. Good bye, Grandpa said. They sealed it with a kiss.

I took her home, drove myself home, and my mother met me at the door: Grandpa’s dead. We picked up my grandmother and she climbed into the back seat beside me and held my hand in her hand and didn’t let go. She said, If you hadn’t taken me to see him I would never have said Good bye.

She’s gone now, too. Her last words to me were: I love you. And your mother. And your father. Very much. Good bye, and she hung up the phone. Now I have all her furniture. I will return for it with a moving truck when school is back in session. Until then, for me, it continues to be the summer of ongoing biopsies, the summer of neuro-opthalmology. It has been a difficult several months. It has never not been a difficult several months, which is why I keep moving and moving, and moving: four cities in the past three years alone. Where next? And will I ever be happy? Will I ever settle down?

When I began this letter to you, Satomi Shirai—strange sister stranger, your exposed back turned away from me—all I could think was: My itch is not your itch. But maybe I was wrong. Perhaps your itch is like mine, in my desire to return home, to a home that no longer exists, or to a home that never existed at all. Or to a home I do not have because I have not yet made it for myself, and perhaps will never make, and never know.

(from The Asian American Literary Review, Fall/Winter 2012 issue.)

Gardening Secrets of the Dead

by Lee Herrick

When the light pivots, hum — not so loud

the basil will know, but enough

to water it with your breath.

Gardening has nothing to do with names

like lily or daisy. It is about verbs like uproot,

traverse, hush. We can say it has aspects of memory

and prayer, but mostly it is about refraction and absence,

the dead long gone when the plant goes in. A part of the body.

Water and movement, attention and dirt.

Once, I swam off the coast of Belize and pulled

seven local kids along in the shallow Caribbean,

their brown bodies in the blue water behind me,

the first one holding my left hand like a root,

the last one dangling his arm under the water

like a lavender twig or a flag in light wind.

A dead woman told me: Gardening,

simply, is laughing and swimming

a chorus of little brown miracles

in water so clear you can see yourself

and your own brown hands becoming clean.

(from Gardening Secrets of the Dead by Lee Herrick. Copyright 2012 WordTech Editions, Cincinnati, Ohio.)