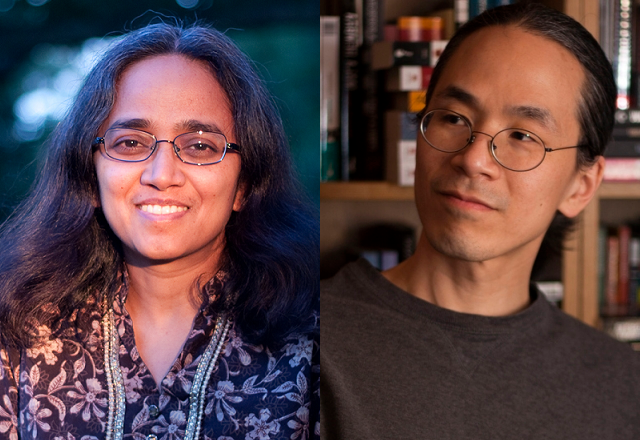

Fellow sci-fi writer Vandana Singh quizzes the award-winning, short-fiction master on his axiomatic approaches, paradigm shifts, and whether he would ever own a digient.

October 3, 2012

Vandana Singh: Your short stories have won all the major awards in science fiction, although at last count there were fifteen stories in just over twenty years. Clearly you value quality above quantity. Can you tell us something about how story ideas first come to you, and how they ultimately become the story? And specifically for your many fans, is there a particular reason why you are not more prolific?

Ted Chiang: There’s no one who wishes I were more prolific more than I do. If I could produce stories more quickly, I would, but by now I think it’s safe to say that my rate of production isn’t likely to increase.

The fact is, I don’t get a lot of ideas that interest me enough to write a story about them. Writing is hard for me, and an idea has to be really thought-provoking for me to put in the necessary effort. Occasionally I get an idea that sticks in my head for months or years; that tells me there’s something about the idea that’s compelling to me, and I need to figure out precisely what that is. I spend some time brainstorming, looking at it from different angles, and contemplating the different ways I might build a story about it. Eventually I come up with a storyline and an ending, and then I can start writing.

I have previously described myself as an occasional writer, and I feel that’s a fair description. Writing fiction is important to me, but it’s not something I feel like doing all the time.

Your stories are cerebral, philosophical, and deeply imaginative explorations of ideas, and I love how so many of them posit and approach fantastical made-worlds in a wholly scientific way. So, for instance, in “Tower of Babylon” you explore an alternative cosmological construct by taking the Jewish story literally and elaborating on the consequences. Another example is “Hell is the Absence of God,” where the god of the Old Testament is assumed to exist as a matter of fact, complete with angels and divine manifestations, and the possible sociological consequences are both plausible and horrific (and I have to say, for me, filled with black humor). While the what-if scenario is supposed to be a standard one in science fiction, there are few writers who take this axiomatic approach to the level that you do. Do these stories come from a particular way of viewing the world? And a possibly related question: how did you come to be interested in science/mathematics, and in science fiction? Did one lead to the other?

It’s interesting that you describe it as an axiomatic approach, as if the stories were non-Euclidean geometries based on differing axiom sets. I doubt many other writers would use that analogy; a lot of science-fiction writers are interested in science, but I don’t think many have studied much mathematics in school. I once heard a writer use “quadratic equations” as shorthand for extremely advanced mathematics, when it’s actually just high-school algebra.

While I always enjoyed science as a child, my interest in both science and science fiction was energized by the work of Isaac Asimov. I read his FOUNDATION TRILOGY when I was twelve or so, and I think it was one of the first novels I ever read that wasn’t written for children. A year later I bought his ASIMOV’S GUIDE TO SCIENCE, which had a huge impact on my understanding of how scientists learn about the universe (I still remember some explanations from it). And there was a definite similarity between the pleasures that both of those books provided; I think the sense of wonder that science fiction offers is closely related to the feeling of awe that science itself offers.

While many of your stories are set in America and feature American protagonists of unspecified race (one assumes white by default) you have also written about and set stories in the Middle East (“Tower of Babylon,” “The Merchant and the Alchemist’s Gate”). To what extent are you interested in race and culture, and the Middle East in particular? Does your being Asian American inform your stories in any way? Will you perhaps write a story set in China, or featuring Chinese characters some day?

Race inevitably plays a role in my life, but to date it’s not a topic I’ve wanted to explore in fiction. Obviously my life experiences inform what I write, but in general I feel the events of my own life are too dull to be the basis for fiction.

I may address the topic of race at some point, but until I do, I’m hesitant about making my protagonists Asian Americans because I’m wary of readers trying to interpret my stories as being about race when they aren’t. People have looked for a racial subtext in my work in a way I don’t think they would have if my family name were Davis or Miller. This is just a special case of something most writers have to contend with—people reading their work in a certain light based on extra-textual knowledge of the author—but I’d rather not do anything to encourage it if I can avoid it.

I can’t say that I feel strong ties to the Middle East; I’ve set stories there because I wanted to make reference to specific story traditions associated with that region: the Old Testament and the Thousand and One Nights stories. If I get an idea for a story that I feel would benefit from being set in China, I would certainly write it.

Many of your stories are about the protagonist gradually discovering something significant about him/herself or their world. One of the most beautiful examples of this is your story “Exhalation,” but it is also there in “Tower of Babylon” and “Seventy-Two Letters.” Does the process of discovery hold a particular fascination for you?

Absolutely, and this is what I was referring to earlier when I mentioned the relationship between science fiction and science. In Clute and Nicholls’ Encyclopedia of Science Fiction (the first edition of which I bought when I was in high school), there’s an entry titled “Conceptual Breakthrough,” which describes the theme of paradigm shifts and discoveries that expand the characters’ view of the world. Nicholls says this theme is so central to science fiction that no definition of the genre can be considered adequate if it doesn’t take this theme into account.

Conceptual breakthrough stories are interesting to me because they’re a way of dramatizing the process of scientific discovery without being limited by history. There are a finite number of paradigm shifts that have occurred in history, and if you wanted to describe them accurately, you’d have to include a lot of slow and tedious data gathering in your account. In science fiction, you have enormous freedom in creating situations in which your characters achieve a greater understanding of their universe. It’s a way of mimicking the mind-expanding experience that science offers, in fictional form.

At least a couple of your stories have to do with artificial life forms, most notably “The Lifecycle of Software Objects,” your longest work to date. One of the things that struck me about that story is how easily the protagonists come to care for their AI creations, the digients. This is not unlike how people care for each other, or their children, or pets (or in extreme cases rocks, or cars). Do you think that there is something in human nature that makes this easy? Can you comment on how this story came to be? Would you adopt a digient?

People have noted that the most popular virtual pets—Tamagotchis, Nintendogs—are ones that demand regular attention rather than acting self sufficient. I think this reveals something interesting about human psychology, but it wasn’t the primary motivation behind “Lifecycle of Software Objects.” Tamagotchis and Nintendogs aren’t actually conscious, and what I was most interested in exploring was what sort of relationship might arise between a person and software that’s actually conscious.

When people care for their children or pets, they are—ideally—engaged in something fundamentally different from what’s happening when people care for their cars. If you’re going to be a good parent or pet owner, you have to recognize that the relationship is not exclusively about you and your needs; sometimes, the other party’s needs come first. That’s not true with cars; no matter how much money you spend on your car, you are ultimately spending money on yourself. I’ve read stories in which characters argue that artificial intelligences deserve legal rights, but I don’t recall a story in which characters put an artificial intelligence’s needs ahead of their own. That was the situation I wanted to write about.

I don’t know if I would want to adopt conscious software as a pet. Part of me hopes that we never develop such a thing, because I think doing so would inevitably entail enormous suffering on the part of the software. The amount of cruelty we inflict on biological organisms doesn’t make me optimistic about how we’ll treat artificial ones.

Finally, can you tell us something about what you’re working on now?

I don’t want to talk too much about what I’m working on, so I’ll just say that it’s a story about memory and the written word.