The acclaimed Thai filmmaker sits down with novelist Katie Kitamura for a conversation about narrative vs. storytelling, black magic, and migrant populations.

June 15, 2012

KK: How do you create time on screen? Tarkovsky famously spoke of “sculpting in time.”

AW: That’s the thing I mentioned about the time of the past but you work in the present. Because you deal with the idea of sitting and going through from point A to point B, and the time is distorted in the present. The time that you want to make the audience feel is different to the actual time. So sometimes you have to make it, well let’s say longer than normal.

KK: Another thing I’m interested in is your use of lighting. Because it feels almost like a character, it feels central to the story telling itself.

AW: Yes, it’s like actors, it’s part of that detail that I have fun doing. For each film it’s a different treatment. For Tropical Malady it’s all these in between worlds of fantasy and reality. Of course you cannot shoot the movie in the real darkness, in the night. The moon’s not enough. So we have to simulate it to a point that for me, in that second part, it’s more like an in-between reality. Whereas in the movie Uncle Boonmee, we rarely used light in the jungle, we used natural light that we tinted to make it day for night shooting. We could have shot at night, like Tropical Malady, but it’s not the same idea—the movie with day for night has a blue tint, so for me it’s like an homage to the old films, that needed really strong sunlight to make it blue as in moonlight.

KK: Is that because in those two films, the jungle is representing something very different?

AW: Yes, that’s right.

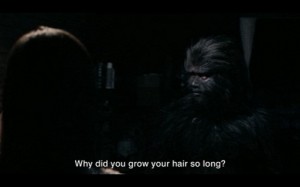

KK: Another key thing in the films is the split between the material world we’re in and the spirit world. But it seems like the spirit world has a very material form—like the catfish in Uncle Boonmee, or the fact that the monkey ghost comes in this great costume. I suppose it’s related to what you were talking about earlier, the opposition between the capitalist urge to acquire more and more material goods on the one hand, and then the spirit world on the other.

AW: Exactly.

KK: How do you render the spirit world on screen?

AW: It’s about reality in real life and in cinema. How you blend or have a dialogue between the two. Especially because when I talk about ghosts, or something, it’s solid. Because when I was young I totally believed in ghosts, and they were solid. So that’s what I’m recreating. At the same time, I’m referencing the representation of ghosts in cinema. This thing that comes to play, in this costume (the Monkey Ghost in Uncle Boonmee)—it reminds of television shows. It’s all this mixture.

KK: In an interview, you described movies as black magic. I was wondering about the relationship between movies and faith, or belief—not in the religious sense, but in the sense of leaps of faith, suspension of disbelief, or incantation.

AW: I don’t know, because for me movie is more than—it’s not religion, but it’s freedom. So it doesn’t tie to any set of beliefs. Of course it ties to this technical aspect, in that they have to fit in each time—I don’t know, whether you’re watching them from the internet, or the cinema, it has this tie in the technological set up. But otherwise, it’s spiritually free. I don’t say that it’s religion, because I don’t believe cinema will liberate anything. But cinema itself—it just represents freedom.

KK: When you say it represents freedom, do you mean that it opens up a space that is suspended from these systems of belief? Is it a political space, or a personal space?

AW: Everything—because there are voices there, that are like individuals. Maybe that ties back to when I say a movie’s like black magic, because it seems to have a life of its own. Each one, when we watch, or when we make movies, it’s—every time it tries to tell me when I’m making it which way it’s going. So I try to accommodate it as much as I can, to make the process of filmmaking quite organic. So I’m ready to change—the script, or during the editing, the structure—to make this animal be comfortable in its own self.

KK: Do you often make radical changes in the edit?

AW: Yes. Quite a lot. In Uncle Boonmee, we originally had the guy talking non-stop, to the end of the movie. But in the end, we just tried many ways, but it didn’t work.

KK: In Tsai Ming Liang’s Goodbye, Dragon Inn, or Hou Hsiao Hsien’s The Electric Princess House, there’s this sense that cinema is haunted. The form itself, and also the physical space of the theater itself. There are a lot of hauntings in your films.

AW: Yes, for me it’s haunting because cinema is about creating life from memory, from the past. But I sometimes wonder if it’s because only for me, or our generation. Because for me I grew up with this, what you mentioned, with Hou Hsiao Hsien and Tsai Ming Liang, the big theater, down to the details: it has to have a screen, it has to have a red curtain. All these things constitute cinema. It’s really more than just the image. All this—the memory of space, of being in this darkness, in the hall.

KK: Do you think the people growing up now won’t have that sense of the movies, because they’re watching them on computer and phones?

AW: Right. Unfortunately, yes. Like my nephew, he doesn’t need this set up.

KK: I worry about being nostalgic, but it seems like something is being lost. It almost feels like there’s a flattening of the screen. It used to be that you entered a separate three-dimensional space to encounter a film.

AW: Literally flattening, for the movie itself, when we are moving toward digital. Digital is never going to achieve the chemical—how do you call it—depth of the film. I don’t say that it’s worse, but it’s the way we’re going. So for me cinema is always romantic. There’s this nostalgic, romantic thing about it, because I grew up that way.