Fabulism as conflict, punchlines, symbolic white space, and more

October 19, 2015

Come see Matthew Salesses read from his new novel alongside Lee Herrick, Tracy O’Neill, and Sung J. Woo at AAWW this Thursday, October 22. Plus, read Ed Lin’s interview with Salesses in The Margins.

I write and read a lot of flash fiction—generally stories under 1,000 words. My first novel, I’m Not Saying, I’m Just Saying, consists of 115 chapters that are each shorter than a page. Many of the chapters were published as individual flash fiction stories. Very short stories go back a long ways—some of my favorites are by Franz Kafka. But they seem to be enjoying a current wave of popularity. Several recent book could qualify as novels in flash fiction, including Justin Torres’s We the Animals, Mario Alberto Zambrano’s Loteria, and perhaps Jenny Offil’s Department of Speculation.

I also teach flash fiction. When I do, I teach a number of “moves” writers can make to pull off a story in so few words. Years ago, I read a list of “moves in contemporary poetry” that Elisa Gabbert and Mike Young compiled for HTMLGIANT. “Moves” are a great way to talk about writing strategies and also to suggest that these strategies are cultural. The following is a list of moves that I see contemporary writers making in flash fiction. I have included examples at times, though often the name of the move seemed description enough. At the end of my list is some crossover with Gabbert and Young’s list of poetry moves, which they explain exceptionally well.

1. Use of definition to start or end a story

“First of all, what is Umami? It is the fifth taste beyond sweet, sour, salty and bitter. Like the sixth sense, there are people who don’t believe it exists. Like intuition, it is more subtle, less quantifiable. My step-father, an electrician, said that once, during the Depression, his boss was hiring a new crew and treated the candidates to lunch at Walgreens.”

—Marc Sheehan, “The Umamist,”

2. A single long sentence

3. Rhetorical questions/ending with a question

“See how easy it is to play a trick on Maidy?”

—Amy Hempel, “San Francisco”

4. Animals as metaphors, ending with animals

5. An all imagined scene or ending with imagined scene

6. Very long title, title with something left out of the story, or title directly from the story

7. Fabulism (something that couldn’t happen in reality) as extended metaphor

8. Fabulism as conflict, or as solution

“Our robots are life-givers. We used to have this advantage over them. Now we have nothing.”

—Rachel Adams, “Robots Make Babies”

9. Puns or jokes becoming part of or even the premise of a story

“Buffalo buffalo Buffalo buffalo buffalo buffalo Buffalo buffalo.” by Lucas Church

10. Clipping or altering a cliche

“The Night I Met Her She Said Once You Go Yellow” (the title of one of my stories)

11. Definition or description by negation

“Things shift. Not the brass headboard or the stack of literary texts beside his computer or the real purry purring on a pillow beside our heads. There’s no quake under the magnolia outside or up the stairwell, nothing knocks against the door of our apartment.”

—Mary Wharff, “Nothing to You”

12. Setting revealing backstory

“We sit on a couple of folding chairs lining the wall and drink our Miller Lite. They don’t have imported beer here and they don’t serve liquor. There’s a table full of food: hot dog buns, Lay’s potato chips, one crockpot full of hot dogs and one full of chili. It’s free but hardly anybody’s eating. We have run out of things to say to each other. This is our third date.”

—Mary Miller, “A Town It Might Not Be So Bad to Grow Old In”

13. Unexplained shocking events

14. Never resolved problems

15. Nonsensical action, or illogical causation, pointless but not toneless

“The projectionist returns from his reel. He pulls my hair until a clump comes out in his fist and he stuffs it in my mouth. I can’t see the film, but I know what is on the screen: Thick carpet.”

—Laura Ellen Joyce, “Cinema”

16. Chained POV (perspective changes from one character’s to the next without repeating)

17. Use of facts to tell a story

18. Ironic how-to-not about how to do something

19. Lists

“You Never Knew the Waters Ran So Cruel, So Deep,” by Roxane Gay

20. A rule as an occasion for a story

My father said we weren’t allowed to….

21. Addressing an unidentified person

22. Obvious ambiguity, especially with endings

23. Borrowing architecture: fairy tale, genre, poetic form, epistolary, etc.

24. Using an unreal character in a real situation

Dinosaur at the office, etc.

25. Numbered sections

26. Ending with an unexpressed thought

“Well there goes Barb down the street, she disappears into the dark. Yeah you can use it Barb, I’m thinking, you can do what you need to do.”

—Meredith Alling, “Street Parenting”

27. Backstory and/or revelation suggested by the ending

“And once, in the rain (only once, only once) with your first, when I told you where I’d been.”

—Sue Williams, “You Beat Me”

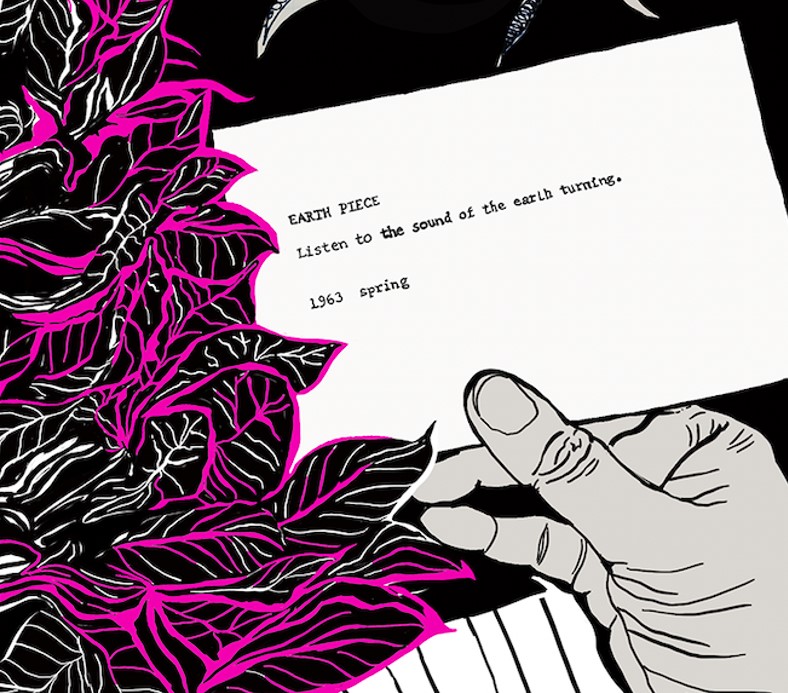

28. Use of commands, as in an instructional

29. Studying a photograph, or imaginary photos

“Frame 1: That night after dinner when I watched her take a translucent, atomic fish bone from her tongue and drop it into the empty wine glass. Frame 2: The time we’d gotten in a fight but she still called me and told me to go outside, to look up at the northern lights. How we sat on the phone together breathing about God.”

—Leesa Cross-Smith, “Ladies Love Outlaws”

30. A pattern broken or altered by the last line

31. Integrated or stacked dialogue

“I know a girl who lives in the ocean and she tells me it’s better than the real world, she says put your ankles together and see what happens, she says float, she says sink, you’ll be fine.”

—Jane Flett, “Mermaids”

32. Flash forwards, especially in the last line

33. Symbolic games

34. Extreme juxtaposition

“I remembered Dodgeball was my favorite game. One time I forced a girl to pull down her underpants. At the end of the road, there was a small bridge.”

—Kelly Fordon, “A Small Bridge”

35. Starting with a story’s one impossible thing

“Is this what you want? he asked, and I said yes, so he took off his skin for me.”

—Maria Hummer, “He Took Off His Skin for Me”

36. Story all in dialogue

37. A single paragraph story

38. Ending with a mundane action off-setting the charged scene (or vice-versa)

“I miss the next stop, and the next. I’ve never ridden the bus this far and don’t know where it goes. Things get more and more unfamiliar: churches and food trailers and second-hand clothing stores, a bakery with a giant cupcake on the roof. A Cuban restaurant. A massage parlor. But then the city turns into every city, and I get off and cross the street, catch a bus back home.”

—Mary Miller, “I Won’t Get Lost”

39. Stacked-up (sometimes associative) backstory

“My husband believes I am seeking comfort, but my mother and I will sit on her back porch and drink the sweet tea she learned to make as a girl in Mississippi, where she also learned that tragedies come in threes and you should spread the cut hair from your children outside the doors and windows of your house to ward off evil spirits. It’s been six weeks since Walter Michael Davis died, and in that time I have felt only the power of his absence. My mother phoned to say she hears my son in the sounds of the wind in tall grass, in the beautiful names of the birds and wild flowers she loves. My mother claims that, when my father died, he flew off with the Cooper’s Hawk we sometimes saw chasing birds in our back yard, that we heard calling from the woods. My mother said she could sense his presence in that call, and I envied her for that. So what do I plan to say when I arrive?”

—Doug Ramspeck, “Three Crows”

40. Direct address transitions

“Here’s something I just remembered: you asked if my full name was Madison and when I said it’s Madeline you said you liked Madison better.”

—Maddy Raskulinecz, “In the Time It Takes Me to Forget You My Hair Will Grow Back to the Way You Like It”

41. Soliloquy revealed to be an address

42. Anaphora, or starting sentences or paragraphs with the same word or group of words

43. Punchlines

44. Answers coming long after questions are broached, especially at the end

45. Ending with a decision that will have consequences past the story

46. Reversals and double reversals

47. What’s really going on is missing, or MacGuffins

48. Unfulfilled desire

49. Materialism

50. Negative desire

51. Ending evoking beginning and middle

“For sale. Baby shoes. Never worn.” —Hemingway

52. Information/backstory given in only one line of the story

53. Character becomes circumstance

See “For the Birds,” by Mark Budman, in which a characters starts to feel like the bird stuck in her wall.

54. Pushy secondary characters who force action from primary characters

55. Symbolic white space

For example, the space break in Hempel’s “San Francisco” as a spacial representation of an earthquake

56. Tone evokes emotion

57. Backstory given in dialogue

Moves in Flash Fiction That Can Also Be Found in Poetry

See “Moves in Contemporary Poetry” for examples.

Use of etc.

Verbing a noun

Use of definition

Rhetorical questions

Ending with a question

Casual hedges (sort of/kind of)

Imagined scene

Very long title

Title with something left out of story

Title repeating something from story

Fake Proper Names

Puns

Clipping or altering a cliche

Definition or description by negation

Compound noncewords

Polysemy: language deliberately meaning multiple things at once

Parataxis

Illogical causation