Our sonorous, sorrowful Korean.

May 1, 2023

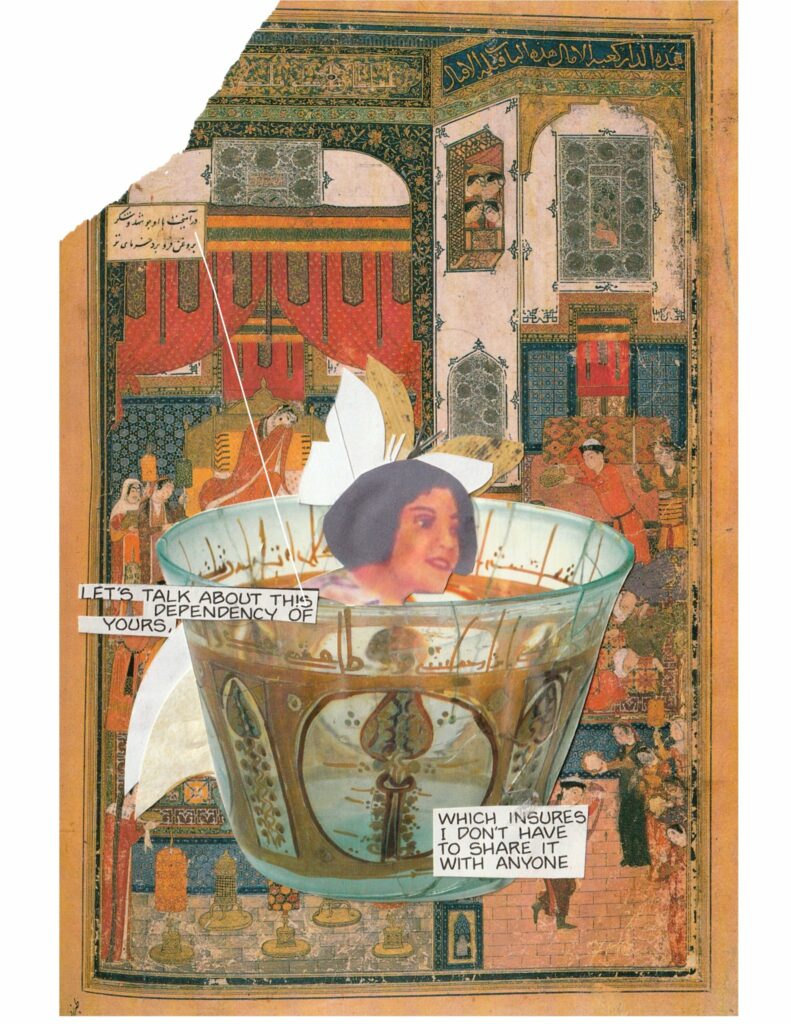

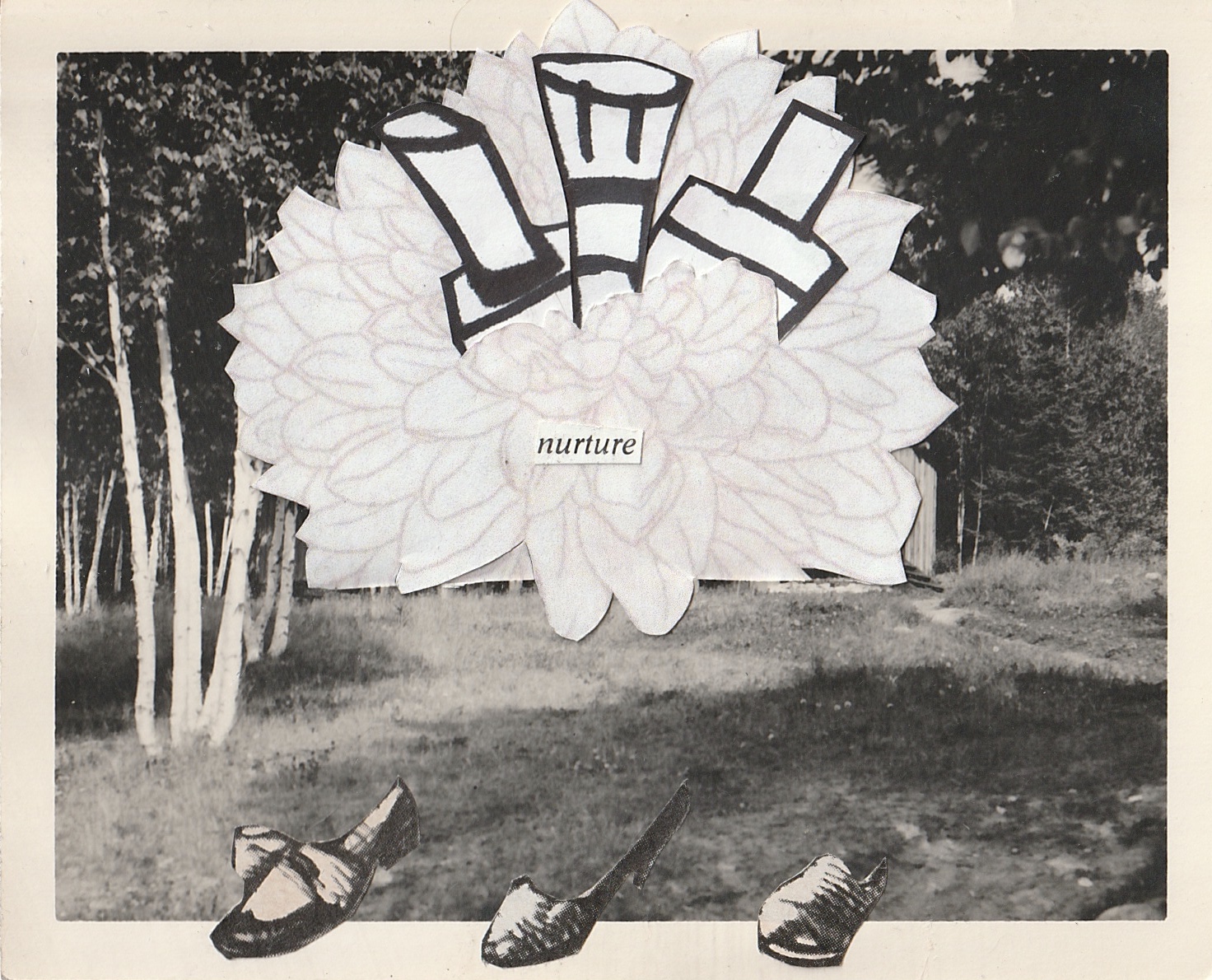

This piece is part of the Love Letters notebook, which features art by Ali El-Chaer.

When the doctor asks me to tell you that you are dying, I say instead in Korean: We have run out of roads.

I miss translating work documents and tax forms. Restaurant menus and scammy advertisements selling gray calcium pellets that promise impossible health.

I lose my Korean phonemes willingly while queuing in triage. All the beds taken, I spit the words for cancer and necrosis and fold them into napkins for your bedside wastebasket.

I don’t say die, but you die anyways.

The funeral director comes out with his mask pulled down below his chin. “It’s okay,” he says. “I already had Covid.” Then he slaps the top of the sample casket like a car salesman.

You can fit so many fathers in this baby, I hear in my head.

By the time the cancer had spread its black barnacles across your lungs then into your blood, after the lung perforations and abscesses opened chasms in the MRI, we really could have fit many of you into that slender box. The final boat to carry you into the earth.

We run our hands against it. Deep swirls in the grain. Mahogany. Sturdy with elegantly carved rosettes in the corners. What would you have wanted? Does anyone truly have strong opinions on felled and varnished trees?

Your wife chooses instead a casket of wide oak. She pays in cash and doesn’t cry. It’s December but it hasn’t snowed. Outside, the day is beautiful.

In translating for my mother-in-law, I make a mistake.

I tell the funeral home that they are not to put makeup on you for your viewing, 화장 being the Korean word for makeup. It is the day before the funeral that I realize it is also the word for cremation. 화 rooted in the Chinese word huǒ—fire. What she meant was she didn’t want you cremated.

I imagine you gray in the silk linings of your casket, your face arrested in hospice ache.

I call the funeral director, half hysterical with laughter. I beg him to put makeup on the body, please. Put makeup on the body. Please. Makeup on the body.

On the day of your funeral, I step out during worship.

The director and some attendants are in the hall, chuckling at the language they don’t know swelling like an accordion in their American halls. When they see me, they scatter. Clearing their throats, their faces at once somber again.

I press my back against the cool white wall and listen. Your family is singing you towards your lord in your vowel-rich language. Our sonorous, sorrowful Korean.

Outside, a kid streaks by on a skateboard, pulled by his leashed dog, whooping to himself.

He’s shouting “Let’s go!” But through the glass, I hear Let go. Let go—