From Bulosan to Hagedorn, this mobile library celebrates Filipinx American literature

September 26, 2017

In 1946, the Filipino American writer and labor activist Carlos Bulosan published America is in the Heart, a semi-autobiographical novel considered to be one of the earliest published Asian American narratives and a classic of Filipino American literature. Drawing off of Bulosan’s personal experiences as a migrant worker in 1930s California, the novel chronicles the anti-immigrant—and specifically anti-Filipino—racism that was on the rise during the Great Depression.

As the economy worsened, and the Filipino immigrant population grew, anti-Filipino sentiment increased. In one scene, the narrator and his brother go on an unsuccessful search for an apartment in a white neighborhood. The first landlady sees them approach and runs out to her yard to remove the “For Rent” sign. “The next woman was more discreet,” writes Bulosan. She offers a weak excuse, “This house is not for rent. The sign is nailed to the wall and it’s hard to pull out.” She sends them down the block, where “the next woman faced the issue squarely. She said: ‘We don’t take Filipinos!’”

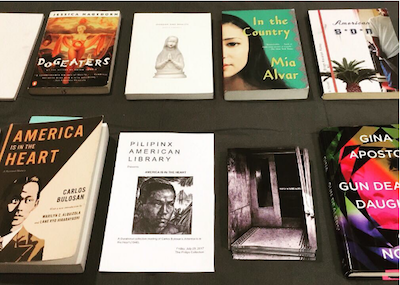

When Filipino American artists Emmy Catedral and PJ Gubatina Policarpio were planning one of the first pop-ups of the Pilipinx American Library (PAL for short), their mobile library of Filipino American literature, they knew they had to begin with Bulosan. For their booth at the Blonde Art Book Fair at the Knockdown Center, they printed up postcards and put up posters of an image taken in Stockton, California in the 1930s, around the time that America is in the Heart takes place.

It shows a doorway, unremarkable except for a small sign that could have been placed by one of the white landladies that Bulosan wrote about. It reads: POSITIVELY NO FILIPINOS ALLOWED. Catedral described the relationship between the posters and their collection of Filipino diasporic texts as kind of a “face off.” “That’s how we’ve been printed and here’s how we’re printing ourselves,” she said. “[PAL] is the clapback to this image.”

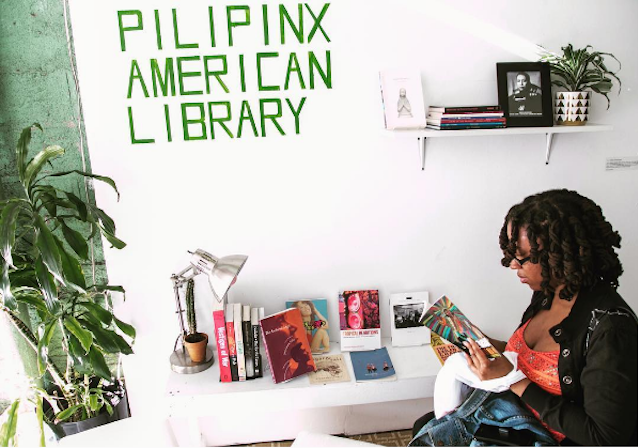

Founded in Queens last summer, the library has made appearances all over the city, including at the Knockdown Center in Ridgewood, Flux Factory in Long Island City and the Jameco Exchange in Jamaica, and were also featured at the Smithsonian’s Asian American Literature Festival in D.C. They currently taking part in an exhibition of artist-run libraries at BAM, curated by the Bushwick-based nonprofit literary space, Wendy’s Subway.

The library’s selection changes from space to space. When I first came across them at the Smithsonian’s Asian American Literature Festival, Policarpio was heading a table featuring contemporary classics: Jessica Hagedorn’s Dogeaters, Gina Apostol’s The Gun Dealer’s Daughter, Brian Ascalon Roley’s American Son. They’ll usually bring as many books as they can carry—Catedral estimated that she brought 40 books to their Flux Factory pop-up “in a backpack and two giant tote bags.”

Originally formed from books taken from Policarpio and Catedral’s personal libraries, PAL has grown rapidly, thanks to unsolicited donations from writers, editors, and publishers in the Filipino American literary community. For a while, Policarpio would set aside $50 from each paycheck to buy used books online for PAL. Their selection is purposefully diverse and democratic, they don’t prioritize novels, academic works and poetry collections over their collection of zines and graphic novels.

The library is a continuation of Catedral’s and Policarpio’s own artistic practices. Before joining PAL, Catedral had curated reading rooms as a part of the Amateur Astronomy Society of Voorhees, a project she developed as an MFA student at Hunter College, which included walking tours, salons, and public workshops related to astronomy. Catedral exhibited libraries of texts about Pluto prior to its losing status as a planet, and works centered around Enrique de Malacca, the South East Asian man who was enslaved by Ferdinand Magellan and was a translator for the explorer while on the first recorded circumnavigation of the globe.

For his multi-disciplinary project the Hinabi Textile Lab, which explored indigenous and contemporary Filipino textile work in an exhibit at the Smithsonian Asian Pacific American Center, Policarpio brought together a library of resources on weaving traditions from around the world.

The library is non-circulating, it operates as a platform for texts that may not be easily discovered otherwise. “It’s an opportunity to be encountered,” said Catedral.

“It is this opening up of a whole world of text by Filipinx writers—to find those private spaces, to stumble upon them, to read them, or just have conversations about them.”

Despite the rich history of Filipino American literature, many people that come across the library are unfamiliar with many of its books. “One of our early statements is just to read these books in public,” said Policarpio. “That is somehow still—for our voices and for our literature—so radical. People come up and tell us “I’ve never read a Filipino American writer before, this is so new to me.””

Their favorite moments at their Blonde Art Book Fair pop-up were when Filipino American attendees came across their table unexpectedly, finding new works by diasporic writers they hadn’t known about previously. Attendees will often spend time reading at the table, or go out and buy the books themselves elsewhere. At the Asian American Literature Festival, many of the books included at the library were conveniently available for purchase from publishers who were also present.

“That possibility, that is what the library is,” said Policarpio. “It is this opening up of a whole world of text by Filipinx writers—to find those private spaces, to stumble upon them, to read them, or just have conversations about them.”

PAL has hosted many of those conversations; the library is as much about its curatorial side as it is focused on literary programming. Most of these events have been organized around America is in the Heart. They’ve hosted collective readings of the text and have also invited Filipino American writers and artists to respond to the novel by sharing personal responses and critiques.

“We really wanted to present this book not as something that’s sacred but as a text that presents a Filipino American narrative of that time,” said Policarpio. “Books are a site for narratives that can be complicated, and [that] reveal so many other Filipino American stories that have been easily forgotten, erased, or just lost.”

The book’s depiction of anti-immigrant rhetoric and violence during the Great Depression has clear resonances with Trump-era America, which was a large part of why they chose it as a centerpiece for their recent events. “People are always saying, ‘This is not America,’ and we’re like, ‘Really?’” said Policarpio, explaining that he and Catedral hoped to “illuminate the ways of racism.”

“It’s never really new,“ he said.

The library’s inaugural pop-up took place at the Plaza Stroll of Queens last summer, a day of arts and community programming hosted by the Queens Museum in the borough’s public plazas. Policarpio, who worked as an arts educator for the museum at the time, reached out to local Filipino American writers for a reading in Jackson Heights’ Diversity Plaza, and brought along books from his own personal collection to share with attendees. Writers Mia Alvar, Gina Apostol, Bino A. Realuyo, and Ninotchka Rosca were among the writers who read at the event, and whose books were included in the inaugural edition of PAL.

Catedral was also present as a reader and contributor at the Diversity Plaza opening, and PAL became a joint collaboration between her and Policarpio not long after. The partnership between the two is one borne out of PAL’s home base, Queens. After the election last fall, they would often meet in Woodside to talk, eat, and decompress. “I think [PAL] is also really a tribute to Queens,” said Policarpio, who recently moved to the Bay Area. “To the 7 train. To hearing polysyllabic community. We would have momos, we would meet, we would have our chai guy, it really was that.”

These meetings and conversations helped frame the work they do with PAL, which offers a unique platform for Filipino American voices that often go unheard in mainstream conversations about race in America. “Being in Queens affirmed for us that we are in a very binary national conversation about race and we were like, where does our role fit in here?” said Catedral. “It’s really American history that we’re representing in this collection of books. It’s just troubling that conversation.”

As librarians, Catedral and Policarpio will often take on a prescriptive role, recommending books to people who stop by at their table. They even wear personalized lab coats and write down book recommendations on prescription pads. When I told them I loved Dogeaters, but had never read anything else by Hagedorn, they recommended her coming of age novel, The Gangster of Love. (As an aside, the two are also huge Hagedorn fans, and unofficially crowned her the “patron saint of the Pilipinx library.”)

“For us, PAL is establishing that lineage. There is something important about realizing that we have always been writing.”

While reading, I was surprised by a scene in which the novel’s scrappy heroine, Rocky Rivera, playfully disses Bulosan to her friend, a beatnik poet called the Carabao Kid, whose name and occupation recall Al Robles, another well-known figure of Filipino American literature. “Bulosan’s a bore,” Rocky complains. “A noble martyr. An overrated, sentimental writer. A mediocre poet.”

I loved the book (they’re very good at what they do), but I was especially moved by this moment of conversation between Hagedorn and the Filipino American writers who came before her.

The vibrance and diversity of Filipino American literature is abundant, and revealing those connections between writers is a central part of PAL’s work. “You can’t talk about someone writing or making art today without thinking about the lineage they come from, whether that’s stylistically or aesthetically,” said Policarpio. “For us, PAL is establishing that lineage. There is something important about realizing that we have always been writing.”

It’s a realization that led Bulosan to his own writing. In America is in the Heart, the narrator ransacks the Los Angeles Public Library in search of creative guidance. To his excitement, he discovers the Asian American writers Younghill Kang and Yone Noguchi. “If there was one, maybe I could do it too!” he writes. And so he did, opening up a new world of literature to be encountered in a library.