Gathering fragments of a changing neighborhood.

June 9, 2012

One late evening in Manhattan, after walking down block after block of shuttered stores, my friend and I stopped into a grocery store near the East River. It was our last hope for the cigarettes she so desperately wanted. But the clerk standing near the register only laughed when she asked him for a pack. However, when we turned to go, he offered my friend a cigarette from his own pack and accompanied us outside to smoke his last cigarette with us. An Italian American man in his late fifties, he had worked in this grocery store for several decades. As we talked, among other things, about his night shift and how he spent his days off, he revealed that he and his family lived in Flushing, where he had also grown up. I braced myself for what so often happened when I met Flushing residents who had lived there before the 1970s influx of Asian immigrants. He said, without a hint of resentment, “Yes, Flushing is nothing like what it was when I was growing up–you can hardly see what anything is about, since none of the signs are in English!” His comment, although expressed without malice, reminded me of other moments when I encountered frustration from other Flushing residents about the predominance of Chinese- and Korean-language signage on the commercial main streets. For many, the multi-story thicket of non-English signage is Flushing, a welcome tapestry of offerings to some, and an illegible reminder of neighborhood change to others.

I find that in the process of delving into the lives of Asian American community members in Flushing, Queens, the question of neighborhood identity and accessibility is still a touchstone for local politics and debate, even as its transformation into an immigrant enclave has occurred over the past four decades.

In fact, long before I came to know Flushing myself, I only knew of one resident of Flushing, an artist who had passed away in 1972 before its transformation into the multi-lingual hub it is today. The self-taught assemblage artist Joseph Cornell lived somewhat reclusively in a small wooden house on Utopia Parkway with his mother and brother, whom he cared for until their deaths. Until I visited Flushing for the first time, it was signified for me by the figure of Joseph Cornell in his mother’s basement, crafting together nostalgic and symbolic worlds in wooden boxes and collaged films.

From his vast collection of ephemera, clippings, and objects organized into more than 160 categories, Cornell assembled layered, three-dimensional landscapes that combined ordinary objects in evocative ways, often organized around themes (birds, the cosmos, dance, travel). He became well-known later in life, but in spite of increasing fame, continued to live in his small Flushing house. However, the dreamworlds in his assemblages rarely if ever included Flushing, and Cornell’s favorite neighborhoods were in Manhattan, where the thrift stores and flea markets that he frequented were located. His fascination with the past led him to mostly collect memorabilia and faded fragments from the Victorian era.

As Flushing continues to change, with the imminent rise of large-scale commercial and mixed-used developments, I think of Joseph Cornell’s boxes as a metaphor for holding memories and projecting desires. What found objects and remnants have been collected by the current residents of Flushing, the new and long-term immigrants? What pieces and fragments will I gather as I travel through the streets, meeting with Flushing residents, workers, community organizations, and local leaders? What follows is the beginning of an assemblage, the hint of what is to come over the next year of writing about Flushing.

—

- Korean dry cleaner and tailors across the street from the municipal parking lot where the Macedonia Plaza project is slated to begin construction. (Sukjong Hong / Courtesy of NYC Economic Development Corporation)

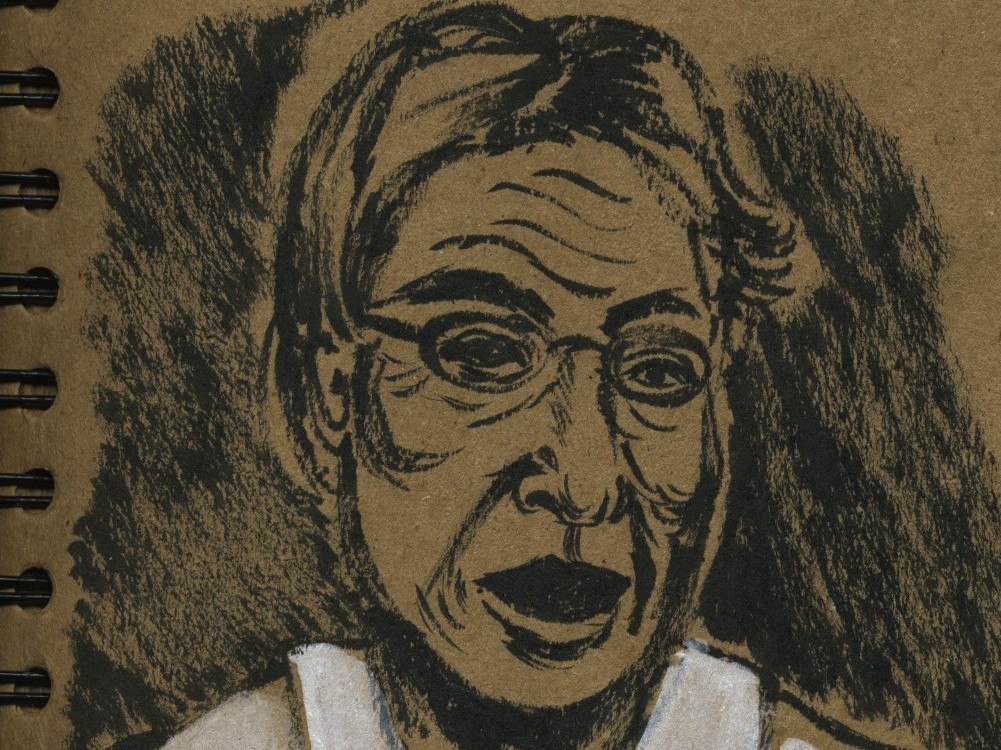

Across the street from the municipal parking lot on Union Street is a dry cleaners and tailors with this figure in the window. I remember there used to be a store that made custom hanbok (traditional Korean clothing), but it is no longer there. There is a long-standing debate about whether the massive new development that would fill in the municipal parking lot will shutter the small businesses in the area, primarily run by Chinese and Korean business owners.

Flushing is where many immigrants living along the 7 line used to dream of purchasing a home, and while many did, it is now one of the hardest hit neighborhoods in Queens in terms of foreclosures. I visited two homes that were listed in the public record as up for foreclosure auction. One house looked empty already; the mail was stacked high, and the doorknob was piling up advertisements for home repair. Are people talking openly about the foreclosure crisis in Flushing, or are they moving away in silence?

In April, during the first overseas absentee ballot for Koreans living in the United States for South Korean congressional elections, I met Mr. Lee, a Korean man in his 60s who had moved back to Flushing from the American South. “At my age, how could I find work there?” He had come back to Flushing because he was hoping to find work. Meanwhile, he asked the South Korean consulate to give him a job, and so during the five voting days, he monitored the door as a security guard.

- Handwritten signs for rent and for roommates flutter in the wind. Students and recent graduates have band practice in the basement next to the grocery store, in a former Internet café. (Sukjong Hong)

Beyond the single-family homes and commercial facades, behind the giant supermarkets and in the basements of stores, the lives of renters—the students from abroad, the new immigrants, the recent graduates living alone for the first time—become evident in the walls of handwritten posters of people seeking roommates and rooms. Through these postings, found in the parking lot of H-Mart on Northern Boulevard, I met a young band, constituted of immigrants from Korea, that rents out a former Internet café as a practice space, along with three or four other bands. Meanwhile, seeking out spaces beyond the bars, restaurants, and karaoke halls of Flushing, they told me about the lack of performance venues where they can perform their music, written in Korean. What is the future of alternative culture in Flushing? Where can youth go to jam?

Housing and displacement, work, public and private space—themes in my own Open City assemblage. This is just the first in a year-long series exploring these and other dimensions of Asian immigrant life in Flushing further.