An art installation in Jackson Heights speaks about how immigrant communities in the neighborhood are experiencing policing and displacement.

February 7, 2017

As salsa and merengue music filled the air, a dark-skinned woman with short hair stopped to ask if this set-up of music and furniture just off the sidewalk was a party.

Jorge Cabanillas, a member of Queens Neighborhood United (QNU), a local grassroots group, spoke with her in Spanish about the public art installation she was looking at.

The art installation, “A Living Room on Roosevelt / Una Sala en La Roosevelt,” was a collaboration between QNU and local artist Ro Garrido. The art installation series took place over the course of three Sundays; each day had a specific theme: immigration, displacement, and policing.

“The idea was to bring an intimate setting to a public space, to talk about what could be difficult issues,” Ro explained. These difficult issues were about how the community was experiencing changes in the neighborhood—from rising rents to businesses closing—and whether they or someone they knew had interactions with the police or noticed the presence of the Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE).

On each designated day, Ro and members of QNU set up a “living room” at Manuel De Dios Unanue Triangle, a public plaza at the corner of 83rd Street and Roosevelt Avenue.

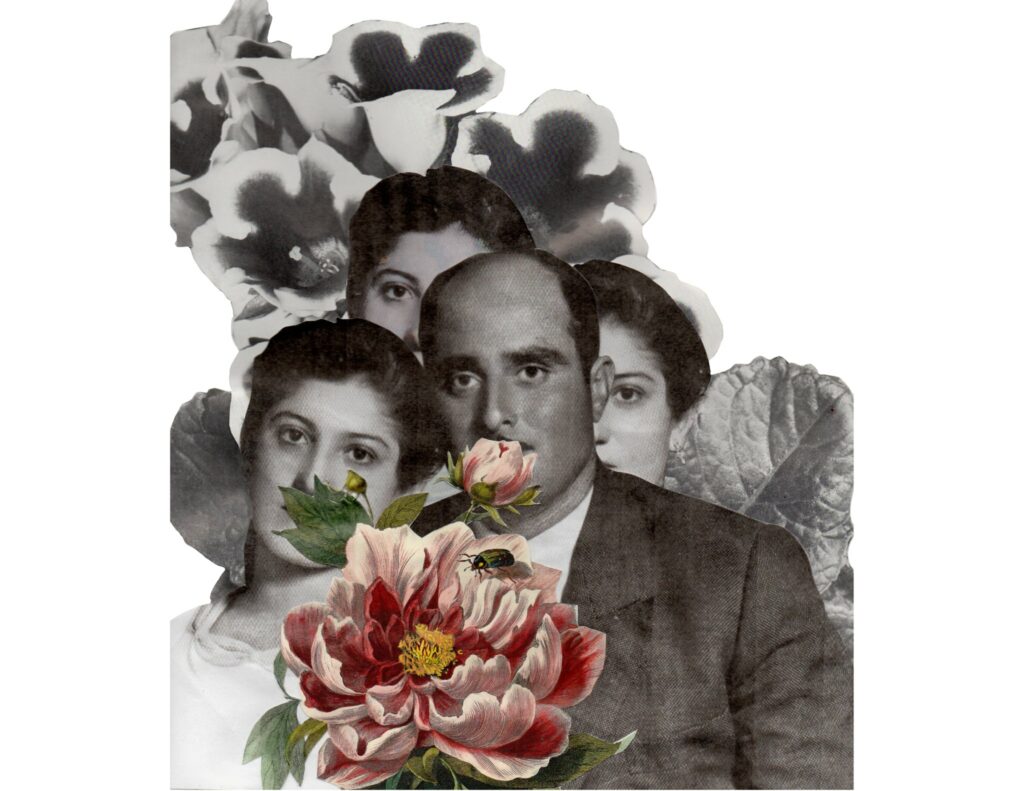

The “living room” has an intentional “throwback feel”, according to Ro. Colorful artificial flowers sat on the middle shelf of the old wooden record player. Two tea cups and a blue tin box of Danish cookie were arranged on the white table runner, that laid on the center table over a rug. A wall made out of cardboard stood behind a paisley-floral patterned couch on a wood panel floor that Ro created. A maroon-flower-print armchair with a white throw on it rounded out the grandparent-aura furnishings.

Ro said it was a journey getting all the elements of the installation together; they borrowed some items from their mother’s living room and purchased other items. All the records were their mothers’ or step-dads’. They said the couch was the hardest to find, because they wanted the couch to look like the couch they had growing up. They were most excited about the record player. “The record player helped situate the installation in a different time,” Ro said.

The installation saw healthy Sunday afternoon foot traffic. Elders, youth and young parents with strollers all walked by, curious about what was going on. Members of QNU were ready to engage the crowd on all sides of the installation. Flyers and brochures in English and Spanish about knowing one’s rights while interfacing with the police were handed out.

A string held up hand-made yellow signs in Spanish that had questions painted on them like, “Do you know what you can ask when you’re arrested?” or statements like, “You have the right to film the police.” Volunteers engaged passersby asking them if they wanted to take a survey that would be used for a policy report.

There was also a “Loteria station,” a traditional bingo-like game, that was set up as a tool for education and engagement. Rows of cards were displayed with a cartoon image in front and related text on the back side of the image. The pictures and corresponding text touched on issues of violence in the community, such as sexual harassment issues, prejudice inflicted across communities such as anti-blackness and Islamophobia, and the criminalization of different marginalized communities such as undocumented people, people experiencing homelessness, and street vendors.

The game aimed to be a tool to generate an understanding of systemic discriminatory policing and also genuine conversations that might challenge people to reexamine their biases and inspire values of interdependence and solidarity. “We hold intersectionality in our experiences all the time, but sometimes it’s easier to create certain divides,” Ro said. They spoke of the importance of breaking isolation and creating a space that could hold many contradictions. They also emphasized how critical it was to create a space where the intersections of migration, displacement and policing could be discussed, especially in Jackson Heights.

Ro grew up in Jackson Heights as did Tania Mattos, one of the lead organizers of QNU who Ro first approached about the installation and collaboration.

Ro’s family is from Lima, Peru and Ro remembers their mother and uncles selling DVDs on the streets to make ends meet when they first arrived in Queens. Ro said their family has felt the impact of gentrification in Jackson Heights; their uncle was forced to close his business recently after struggling to keep it afloat for a long time.

Tania came to Jackson Heights when she was 4 years old from La Paz, Bolivia. She recalls being with her mother while she sold Bolivian food at Flushing Meadows-Corona Park. Her entire family lived in a one-bedroom apartment when they first arrived. She got involved in QNU because she saw her community changing – with a heavier police presence and rising rents that forced her family to move. She recalls being fearful of their home being raided by immigration.

According to QNU, gentrification and hyper-policing in Jackson Heights are systemically linked. Indeed, when City Councilwoman Julissa Ferreras introduced a “New Deal” for Roosevelt Ave, she included “future projects”, such as the 82nd Street Partnership for the expansion of the Business Improvement District (BID) and plans to “create a task force to fight the prostitution and illegal businesses on the avenue.”

Watch video of “A Living Room on Roosevelt / Una Sala en La Roosevelt”. Video produced by Milton Xavier Trujillo.

QNU was formed as a result of organizing efforts against the proposed expansion of the BID. The organizers surveyed more than 1,000 people on Roosevelt Avenue, speaking to businesses, vendors and workers about what the BID was and how it would impact them. Many were not aware of the process it entailed to vote on it, or the implications of a tax on property owners, which would trickle down to increased rent. QNU protested the BID in part for being an inaccessible and undemocratic process.

What the BID promises in return for the tax are services such as sanitation. Diego Palaguachi, a QNU member who came to Astoria from Ecuador when he was 11 and has had to move with his family on more than one occasion due to increased rent, calls the BID a “neoliberal policy that uses the disguise of “cleanliness” and “safety” to privatize public space and public services.”

“What do we mean by cleanliness and for whom is this safety being constructed?” he asks.

Indeed, barely a week after the first Sunday that “A Living Room on Roosevelt / Una Sala en La Roosevelt” went up, State Senator Jose Peralta evoked the same rhetoric that Ferreras did three years ago. He called for the “clean-up” of Roosevelt Avenue, deeming it “the new old Times Square.”

He called for the return of Operation Impact, a program that placed rookies in “high crime” zones, which was discontinued and replaced. Peralta’s call for increased policing of businesses along Roosevelt Avenue is worrisome, given the recent investigation that revealed nuisance abatement actions almost exclusively target businesses in minority neighborhoods.

Peralta’s evoking Times Square is no coincidence as Times Square disneyfying was a concerted effort by the Times Square Business Improvement District and the rollout of Former Mayor Rudy Giuliani’s broken-windows policing. A recent government report showed what advocates have known for years, that broken-windows policing doesn’t make New York safer.

“As someone who is interested in how we create safety in our communities—in our neighborhood—that doesn’t rely on police or prisons [and] creates safety outside of these systems, it feels like a really hard road—to create those alternatives,” Ro said.

QNU member, Tricia Chou said that roughly a third of the community members surveyed said they did not trust the police. There was hesitance and fear when engaging people around issues of policing and immigration. “People would ask, you’re not immigration, right?” said Ro. They said they understood the apprehension. “I have a lot of empathy for people trying to survive.”

Ro said it was the small, quieter moments that felt special—kids hanging out, older folks wanting to sit near the record player and listen to music—“I do think it opened up a different space for connection. Even though you were in public, it was easier to forget where you were.”

One older woman approached Ro and said, “This is really beautiful. Everything here is so beautiful.” Ro said it made them feel seen. “She didn’t even elaborate and I could feel what it meant.”

The most recent update regarding expansion of the Roosevelt Ave BID is that plans have been abandoned—a decision that QNU is applauding as a victory. “Most of all, we are proud of and commend all community members especially the small business owners, vendors and workers for coming together to defend our community and what we built,” Tania Mattos said in a statement quoted by the hyperlocal publication DNA Info. “Roosevelt Avenue is not for sale.”