Bill Cheng talks us through his five favorite blues musicians, and how their work inspired his debut novel.

August 28, 2013

Bill Cheng began writing his debut novel Southern Cross the Dog while he was getting his MFA in fiction at Hunter College. When he showed early drafts of chapters to other MFA students, they were all convinced that it was, in some way, a story about Hurricane Katrina—which took Cheng by complete surprise. His novel begins with the Great Mississippi Flood of 1927, a disaster so devastating that it has been immortalized in literature and music, most memorably in the blues. Blues musicians wrote more than two dozen songs about the flood in the two years that followed. But Cheng says his novel is not a book about a flood. “It’s about disaster and being uprooted. It’s about the fragility of the future.”

Cheng started listening to the blues when he was in high school and was teaching himself how to play the guitar. One of the first songs he learned to play was Cream’s “Layla,” which led him to Eric Clapton, and then to B.B. King. “Listening to King I thought, my God, every note he plays, I can feel, like a scalpel blade moving through you,” Cheng recalls. “And from there, I just went in deeper, further back. To Muddy Waters, to Robert Johnson, to Charley Patton. And then I listened to everyone in between.”

“I’m not a musical historian,” Cheng admits. “What I know about the blues are the sounds—a musical hook; the kind of delivery; the sound of a string snapping against a fretboard. I remember sitting at my desk, pitched forward with my earbuds wedged into ears as these sounds poured into me. There was something—I don’t know what—in the timbre, in the cadence that stirred me up in a way that nothing I’d ever heard on the radio ever before had.”

We asked Cheng to introduce us to his five favorite blues musicians, and the songs that served as a soundtrack to writing his novel.

Bill Cheng will be reading from Southern Cross the Dog tomorrow, Thursday, September 29 at 7pm, alongside acclaimed vocalist and composer Imani Uzuri, performance poet Tyehimba Jess, and journalist Siddhartha Mitter. For event details and more info, click here.

1. John Lee Hooker – “Tupelo”

I first saw my book in the voice of John Lee Hooker. I was watching a video of Hooker on YouTube, a recording of the song “Tupelo.” In the video, Hooker looks off to the right, his ears muffed by headphones. His face is wan and feline as he looks off-camera. He taps his foot. The beat is steady, un-rushed, easy. Then there’s the opening riff, a warm and oaky burble of notes. Then Hooker speaks in a deep warm purr.

I first saw my book in the voice of John Lee Hooker. I was watching a video of Hooker on YouTube, a recording of the song “Tupelo.” In the video, Hooker looks off to the right, his ears muffed by headphones. His face is wan and feline as he looks off-camera. He taps his foot. The beat is steady, un-rushed, easy. Then there’s the opening riff, a warm and oaky burble of notes. Then Hooker speaks in a deep warm purr.

“Did you read about the flood along time ago?

A little country town way back in the east. Tupelo, Mississippi.”

Between each phrase, his guitar trickles in—a counterpoint to the drone of his voice like the rolling of water. If your volume is turned high, you can hear the breath slide in and out of his body. The video fades into images: devastating waters swallowing up homes. Flood water coursing in wide swaths. Trees whipped and throttled. “Women and children screaming and crying, saying ‘Lord have mercy. What can we do now?’” And I knew I saw the first chapter of my book, the central conceit unfolding: a flood, almost supernatural in its destructive power, and the people that would live in that shadow.

2. Robert Johnson – “Hellhound on My Trail”

It’s hard to talk about Robert Johnson without getting snarled up in his mythology—Johnson’s journey to the crossroads, his deal with the devil, and his tragic end poisoned by a jealous rival. To many, this story is a primer into the blues—a supernatural cautionary tale of unchecked ambition, good and evil, and the collection of cosmic debts. But, in my view, I think this obscures something more vital, more primal in his music. In “Hellhound on my Trail,” Johnson sings:

“I’ve got to keep moving. I’ve got to keep moving. Blues falling down like hail.”

“I’ve got to keep moving. I’ve got to keep moving. Blues falling down like hail.”

His voice is nasal, haunting. The notes rain down in a bitter drizzle.

“And the days keep following me. There’s a hellhound on my trail.”

The song continues on. There are couplets about women, about sex, and hoodoo tricks. And it’s easy to be misled into thinking that this is an extension of the larger ghost story of the Robert Johnson legend. The song is mournful, yes, not about death, but the trials of being alive. It is a song about discontentment. It is about loneliness, and resignation, and our inabilities to lift ourselves from our own lives.

And this, I think, is the legacy Robert Johnson has left behind him.

3. Son House – “Death Letter Blues”

There’s footage of Son House captured during the folk revival of the 1960’s. By then he’d been around for decades. He’d known Robert Johnson when Johnson was just an upstart trying to hang out with real blues singers. In the videos, House is lanky and gaunt. Most of the time he seems lost, uncertain. In one video he is hectored by Chester Burnett—the 300 pound, 6’6” dynamo that was Howlin’ Wolf. Wolf is young, imposing, brimming with sexuality. House in contrast is old, small, maybe drunk. He is out of place.

There’s footage of Son House captured during the folk revival of the 1960’s. By then he’d been around for decades. He’d known Robert Johnson when Johnson was just an upstart trying to hang out with real blues singers. In the videos, House is lanky and gaunt. Most of the time he seems lost, uncertain. In one video he is hectored by Chester Burnett—the 300 pound, 6’6” dynamo that was Howlin’ Wolf. Wolf is young, imposing, brimming with sexuality. House in contrast is old, small, maybe drunk. He is out of place.

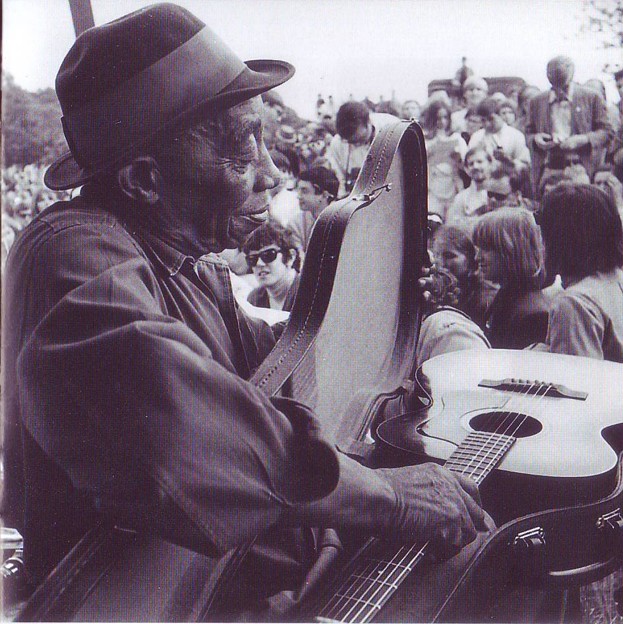

There’s a video of Son House from that period playing one of his signature songs, “Death Letter Blues”—about a man who discovers his sweetheart has died. House’s guitar sits tucked to his chest, and his hand moves to strike the strings. There is something wrong in that movement. His arm trembles. The fingers are stiff, palsied. The guitar clangs out like a junkheap. In some recordings, you can hear the small sputtering breath inside House’s chest.

He strikes again. Off rhythm like he is remembering himself. But a few seconds in, something clicks into place. House rocks forward in his seat. His shoes stomp out a beat. In the noise, a pattern shakes loose.

“I got a letter this morning. How do you reckon it read?”

His singing is explosive. It seems to take everything out of him. But he keeps on.

“How do you reckon it read? Said, ‘Hurry hurry. The girl you love is dead.'”

House becomes a combustion engine, hammering back and forth—the pistons of high notes and low notes, charging ever forward like a mad heart.

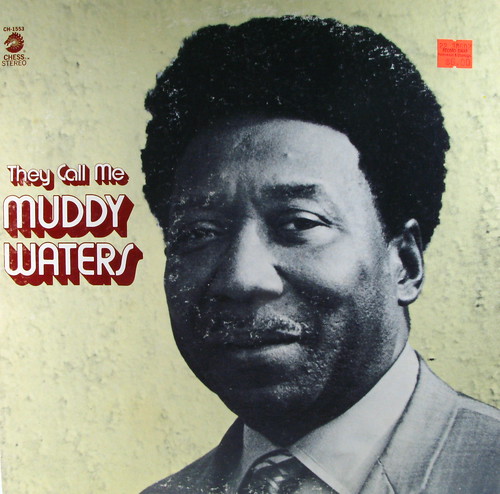

4. Muddy Waters – “Hoochie Coochie Man” / “I Got My Mojo Working”

I first learned about hoodoo in the music of Muddy Waters. It’s a rural black folk tradition that uses totems and fetishes, and all manners of roots and conjurations that can call down fortune or ward off evil. The symbology reappears all throughout the blues: goofer dust, hot foot powder, nation sacks and mojo hands. But no singer conveys the full power and meaning of those items better than Muddy Waters.

I first learned about hoodoo in the music of Muddy Waters. It’s a rural black folk tradition that uses totems and fetishes, and all manners of roots and conjurations that can call down fortune or ward off evil. The symbology reappears all throughout the blues: goofer dust, hot foot powder, nation sacks and mojo hands. But no singer conveys the full power and meaning of those items better than Muddy Waters.

Consider the blues staple, “Hoochie Coochie Man.” It opens with the tell-tale riff, a five note bark that has since become synonymous with the blues. The notes seethe with testosterone and attitude. After a silence, the riff comes again—the snap of drums, a twang of a guitar, and above it the brassy squawk of a harmonica.

“Gypsy woman told my mother,” Muddy sings, “before I was born.

“You got a boy-child coming. Gonna be a son of a gun.”

Muddy sings in stops and starts, lets the band fill the void around his phrases.

“Gonna make pretty women jump and shout.

“then the world’s gonna know, what I’m all about.”

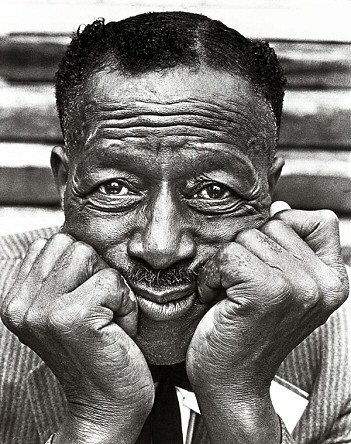

The song itself is a creation story about the birth of a primal, sexual force and Muddy Waters is the perfect candidate for its manifestation. On stage he stands before the microphone, back straight, not a wrinkle in his perfect suit. A pencil thin mustache rims his upper-lip, and he wears his hair in a well-coifed bouffant.

“I got a black cat bone,” he sings. “I got a mojo too. I got a john the conqueroot. Gonna mess with you.”

Then the band howls into the chorus. Muddy’s eyes are held in a sleepy droop—a calm cool center—as the manic noise of pianos and guitars frenzies behind him. He is cocky, dripping sex and cool. And in the hands of Muddy Waters, hoodoo is not some folksy superstition. It is agency. It is power. It is authority. A defiant act against a malevolent world.

5. Mississippi John Hurt – “Lonesome Valley”

In many ways, the blues is a landscape of suffering. The genre spins tale after tale of bad luck and bad choices. And yet, I listen, not because I’m a masochist, but because in spite (or maybe because) of this, I believe this music elevates me. I believe that among these lonely hearts and treacherous women and mean-hearted men, you can also find a joy, a kind of communion. In the mad and senseless arrangement of our lives, the blues gives us this moment to locate one another. To feel unalone in our grief.

When I listen to Mississippi John Hurt, it is hard not to feel this way. I love many of his songs but chief among them may be “Lonesome Valley.” There’s a video of him with Pete Seeger’s television program Rainbow Quest. In the video Hurt exudes gentleness. He is soft-spoken, eager to smile.

He starts to play. A melodic line bounces steadily to and fro, while underneath, notes tickle out shimmering and harp-like. When he sings, Hurt’s voice is high and sweet:

“You got to walk this lonesome valley. You got to walk it for yourself.”

There is no bitterness, no irony.

“Ain’t nobody here can walk it for you. You got to walk that valley for yourself.”

And in this simple refrain, I’m moved by his humility, by his sufferance but most of all I’m moved by the simple fact that this man left this world long before I had come into it. And I feel all at once that my life—the things and people in it—are at once both impossibly small and impossibly large.