I know what it is like to travel into the quiet dusk, but don’t know what her fear felt like.

March 24, 2023

Going South

The train accelerates slowly as it leaves the city, smoothly, quietly. It sneaks away, it steals gently into the night. It swings west, towards Jinan, where I’ll be meeting a friend. The sun, red behind the city’s haze, disappears as the train rounds out of the railway station, smoothly shifting on the embankment as if readying itself for unhindered acceleration. Speed is queen, and as the train enters the straight track, we subdued passengers hurtle forward at two hundred miles per hour, beginning to rock into a gentle sleep.

I dream of fumbles, of moments of disaster, dropping everything, the moment of anxiety when I handed my ticket and passport over at the check. The worker flipped to my photo, looked at the name on the ticket, and experienced a moment of incongruity. It would be better if you just gave me your biometric national ID, he said. It would be better means you had better. I do not have one. You don’t look like a foreigner. But he clicked the ticket anyway so the line wouldn’t get held up. This is the uneasy part of returning, a process that comes in fits and starts, a process defined by friction and flow.

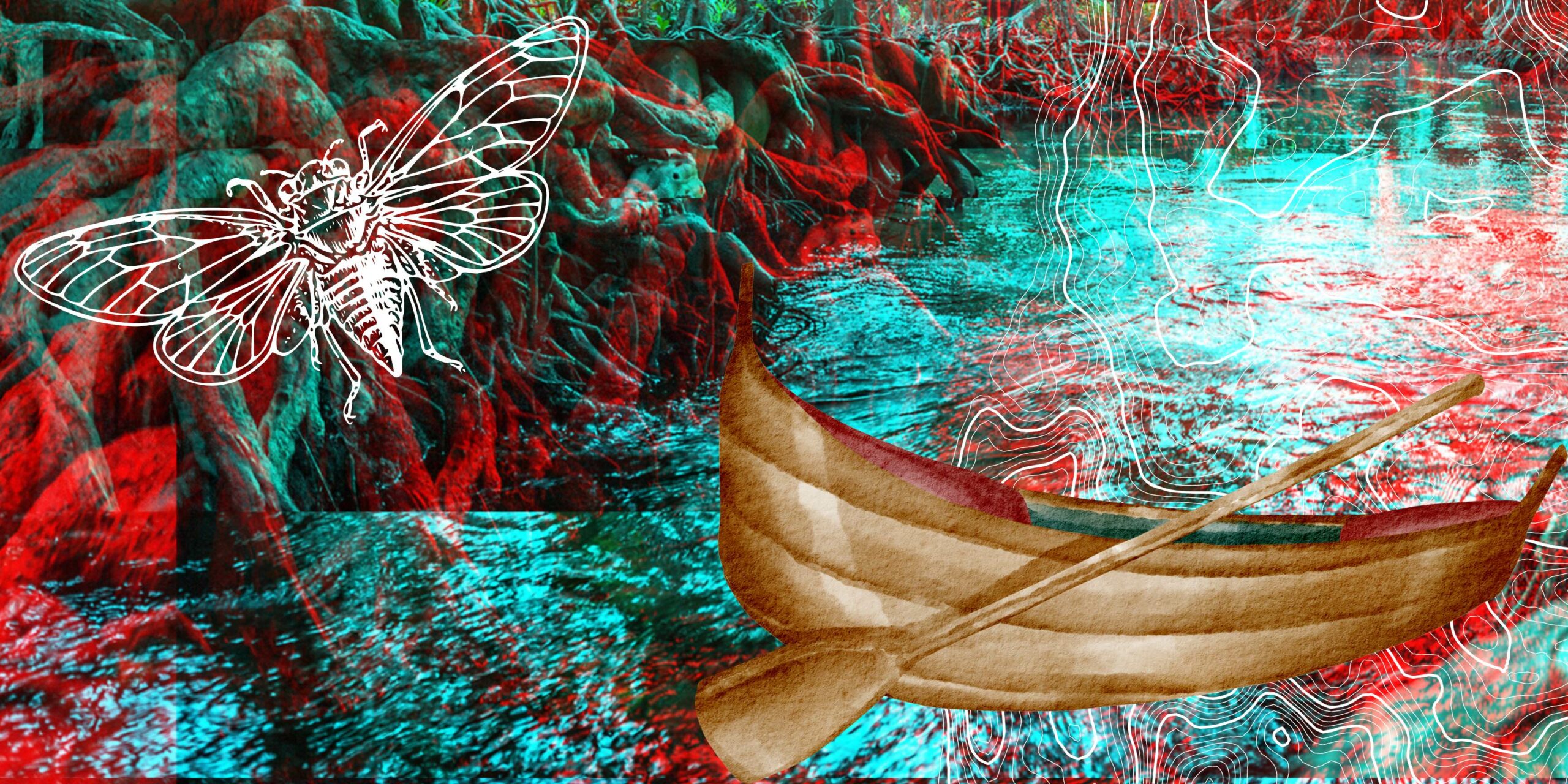

My grandmother left Jiangmen in a rickety wooden boat under the cover of darkness, bound for Hong Kong. The Fuxing train rides gently into the dusk, as her boat once did. But she traveled on in the dark of the night, quiet with the other children and her father and mother. The boat was overcrowded, their bodies cold. The only things that were warm were the jades sewn into their clothes, and even those secret treasures were fast losing heat. The boat hugged the mangroves along the coast as the sun set, crossed the strait in the dead of night. My young grandmother, Beautiful Cicada, used to hearing the cries of cicadas, listened only for the whine of the Japanese airplanes overhead. I know what it is like to travel into the quiet dusk, but don’t know what her fear felt like. My grandmother and her brothers and sisters and mother stepped onto dry land, British territory, and planted themselves there. But my great grandfather returned, to his death. He pacified the Japanese with a chicken and a bowl of eggs, but how many chickens, how much rice, would it take to keep his village safe?

No Memories

Grandmother returned to her hometown only once after immigrating to America. She returns to spend more time in Hong Kong, a place with better memories. As an aimless young adult, I went along with her to visit her high school classmates; not much else to do over the summer. We met her oldest friend, Daphne, to eat at Maxim’s. It’s a special occasion—a reunion—and I like chicken feet, so to please everyone we got two kinds: classic and a savory, garlicky type dark with vinegar. I remember stripping the tendons from the bone with my teeth, mouth eager, technique admirable. I’m thinking of going to Shenzhen for a day, I told them. I want to see it. There’s no need, they said. It’s a city with no history, no memories; the name means deep ditches and now it’s just skyscrapers, gleaming and gorgeous and impersonal.

This is typical of the fierce pride that defines inter-city rivalries, so I drop it, focusing on the bones littering our plates. With Daphne, grandmother reminisces about when the Star Ferry was the easiest way to get to Central, the time Dorothy fell into the harbor. They are insistent on using their English names, holding onto that memory like a life preserver, a tether to what must remain. But I am naïve. Kowloon doesn’t seem like it’s changed much since Chungking Express was filmed: trinket and wholesale shops run by South Asians dot the alleys near Chungking Mansions. Diners still offer simple spam and egg sandwiches, macaroni soup in chicken broth, cups of rich milk tea. The same tastes, textures, flavors, moments woven into their lives from when they were nursing students are all still there. And they are here. But for my grandmother, seventy years later (give or take) Hong Kong’s sprouted a forest of skyscrapers, Beijing is all shopping malls, and Shenzhen glitters on the other side of the strait, a Special Economic Zone, a competitor, a fever dream. A part of the metropolis that swallowed our ancestral home whole.

Port Arthur

Hong Kong maintains its dignity. Here, see the ferry, the Peninsula, the stock markets, the shopping malls, all opened up within twenty-four hours of a super typhoon. Or so the tour guide on Lantau Island told us while we milled through an old-fashioned market, pausing to admire the dried fish. It’s like when I was a little girl, my grandmother says. We mull over what it would take to secret it through customs.

One day, shortly before our flight back to New York, we took the bus out to Port Arthur to visit another one of Grandma’s high school classmates. As the slightly tattered minibus wound along the highway, we could see straight out over the South China Sea. The scent of salt air, warm, fragrant and fresh, filtered in through an open window. We rounded a bend, and the ocean came into view. It was flat, serene, dotted with little green islands and tiny fishing boats, and my grandma looked out and I couldn’t tell if what I saw on the side of her cheek was a drop of sweat, or a tear. Maybe it was a sunny day like today when her father went home, to die.

For our family, Hong Kong’s history is heavy with so many memories that it weeps, the sticky condensation a tangible form of the pain rippling beneath the gleaming shopping malls and pavilions and business as usual. Yet, despite the pain, we are drawn here, three generations of us, again and again over so many years. We jostled over the Pacific on the way home, we flowed through customs at JFK, easy, frictionless. And when we steamed the smuggled fish on top of minced pork, we were there again, again in this recursion, in this returning.