In 2012, over half a million stop and frisks took place citywide. Half of these involved persons of color—young men like Nilesh, who are constantly on the lookout for patrolling officers.

January 28, 2014

[Editor’s Note: Today we’re launching our three-part series on policing in Jackson Heights. Each article examines the relationship between residents and the police in this culturally diverse Queens neighborhood–one in which the NYPD logs high rates of stop and frisk, even as street crime remains relatively low.]

“When it is racial, we cannot see the fun it in it. It frightens us. We suddenly see the snarl on the tiger at the other end of the tail these same police are holding for us. We tell ourselves hastily we do not want the black people of Harlem to be slaves . . . but we do like them to be a little servile. After all, we are all a little servile to the police.” – Truman Nelson, The Torture of Mothers (1964)

Living with Stop and Frisk

“There are three sounds it makes: a bell sound, a crash sound, and like an explosion.”

Nilesh Vishwasrao’s first year at community college is well under way, but high school memories of bag checks and body scans remain fresh. Every day, students were required to swipe their ID cards, which triggered an auditory clue to their disciplinary status.

“The bell is ‘you’re good, you can go on,’ the explosion is ‘this person isn’t supposed to be here,’ and the crash is ‘you gotta go to the dean’s office,’” he explained on a smoke break not far from his home in Jackson Heights.

During his freshman year, Nilesh was nabbed for carrying marijuana. Ever since then he had a hard time shaking school police.

“I think I got the crash sound more times than the bell,” he recalled.

These days, when he’s not studying for school or messing with blues riffs at home, the lanky, black-clad guitarist craves a quiet stoop like this one on 75th street where he can pull out his tobacco pouch and rolling papers.

The perils of metal-detectors are far behind him now, but so are aimless afternoons chilling with friends. These days, when he’s not studying for school or messing with blues riffs at home, the lanky, black-clad guitarist craves a quiet stoop like this one on 75th street where he can pull out his tobacco pouch and rolling papers.

Since high school, Nilesh has had twenty stop, question, and frisk (SQF) encounters with cops—so he’s careful about how he appears on the street. In unison, he lifted a bright green envelope of tobacco in one hand and a rollie crinkled between his fingers in the other. It’s a ritual he repeats to remind prying eyes he’s toking nicotine, not marijuana.

“I don’t want to give any cop any reason to think this is weed. [So] I’ll pretend I have to get something out of my [tobacco] pouch… when I have this in my hand,” he said, eyeing his cigarette.

In 2012, over half a million SQFs took place citywide. Half of these involved persons of color—young men like Nilesh, who are constantly on the lookout for patrolling officers.

The blatant racial discrepancies of SQF statistics proved so jarring, they vaulted Bill De Blasio to the top of last year’s mayoral race, giving him a historic mandate to forever alter or end the practice as New York has known it. Exit poll data made De Blasio’s advantage plain in the Democratic primary. Writing for the Guardian, Ed Piklington, explained, “voters who thought ‘stop and frisk’ was excessive swung behind [De Blasio] by a whopping 56%.”

Recently, in his inaugural address, the new mayor vowed again to reform the “broken … policy,” but not to do away with it altogether, hinting that officers still needed it in “driving down crime.” Last month, he also tapped William J. Bratton, who led the NYPD in the mid-90s, as the city’s next police commissioner, and touted him as a leading voice for “community policing.” Grassroots advocates have expressed skepticism of Bratton’s commitment to less aggressive tactics in light of his strong espousal of zero-tolerance strategies like “broken windows theory” in addition to the top cop’s own record on SQFs; at his last gig in Los Angeles, police stops rose dramatically soon after his arrival.

Jackson Heights, where Nilesh grew up, has logged some of the highest SQF rates over the last few years. The neighborhood’s police precinct, the 115th, ranked third citywide in 2011. However, compared to other top SQF precincts, rates for street crimes (assaults, robberies, and shootings) in this neighborhood are low.

Last month, he also tapped William J. Bratton, who led the NYPD in the mid-90s, as the city’s next police commissioner, and touted him as a leading voice for “community policing.” Grassroots advocates have expressed skepticism of Bratton’s commitment to less aggressive tactics…

Here, Latinos, not Blacks or Asians–are much more likely to be stopped. However, South Asian community organizations in New York like Desis Rising Up and Moving (DRUM) report that teens and other young people in Asian communities–particularly those from working class backgrounds–have experienced increasing police harassment in schools and on streets, which they attribute to counter-terrorism efforts following 9/11.

“How do you think it feels to be stopped by officers when you are just walking home?” asked Manny Yusuf, a DRUM youth organizer, during her testimony at a City Council hearing in October of 2012. Yusuf and fellow DRUM member Naz Ali linked concerns about Stop and Frisk activity to religious profiling and surveillance of Muslim communities.

Historical Origins of SQF

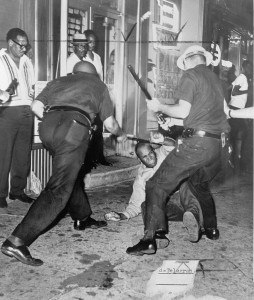

Almost fifty years ago, in the summer of 1964, SQF became official police procedure when the New York State Legislature amended the Code of Criminal Procedure. Dubbed “Stop and Frisk” at its inception, Section 180-a allowed police officers to stop and request identification from individuals upon a “reasonable suspicion” of criminal activity—a standard lower than the “probable cause” requirement for making an arrest. The bill’s passage earlier that spring roused the ire of civil rights groups and local bar associations.

“Nowhere in the history of Anglo-Saxon jurisprudence have we so closely approached a police state as in this proposal to require citizens to identify themselves to police officers and ‘explain their actions’ on such a meager showing,” the New York State Bar Association proclaimed in a March 3, 1964 public statement. The local NAACP chapter organized a rally days afterwards, keenly aware which community would bear the brunt of the new policy.

“The framework is that, statistically, black people commit more crimes than whites,” said Dr. Khalil G. Muhammad, the director of the New York Public Library’s Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture. However, in 2012, eighty-nine percent of stops ended with nothing to show but proven innocence after a trial by frisk.

Dr. Muhammad, who has studied the link between race and crime in American history, believes New York’s SQF policy is nothing new. In a recent interview at his office in Harlem, he traced these practices to an earlier era–from the first generation after slavery through the early and late 1900s–when Southern blacks moved to northern cities in the “Great Migration.” “The narrative of black people and crime becomes more influential on the ground in white communities that are butting up against the increasing presence of black newcomers,” he noted.

The practice, Muhammad insisted, only seems new because stories of urban policing in the North were “drowned out by the naked, brutal terrorism in the South,” where lynch mobs presented a threat and spectacle that daily police micro-aggressions, and even beatings, did not.

Black communities resisted these tactics from the beginning. Truman Nelson’s The Torture of Mothers, published the same year Section 180-a passed into law, discusses one of these first eruptions of resistance to SQF, the Harlem Fruit Riot, an incident that occurred after several young African American boys allegedly turned over a fruit stand. As the story goes, when Harlem bystanders saw policemen beating up the young boys and intervened with questions, the police turned their attention to the bystanders and began attacking them.

Nelson writes, “[A civil rights worker] felt that the immediate cause of the obvious unrest was two new laws, the ‘No Knock’ and the Stop and Frisk laws. The people in Harlem felt that the laws were particularly addressed toward them, and in the hands of an agency as corrupt . . . they could be used badly against them . . . The Stop and Frisk law could have [the] effect [of] giving the police the power to stop anyone on the street and manhandle them, without papers, and with every opportunity to plant evidence in the pockets of whomever they chose to affront in this way.”

Today, Commissioner Bratton asserts that the problem of stop and frisk has been “more or less solved.” Amidst tremendous community pressure and a federal class action lawsuit, the number of SQF encounters last year dipped by 60%. The federal case, however, is still on appeal. The complaint in Floyd et al. vs. City of New York alleged that the NYPD’s use of SQF violated constitutional protections against racial profiling. Last August, trial judge Shira Scheindlin agreed, finding the Department liable and mandating a comprehensive reform process.

Around the same time as the first wave of the “Great Migration,” European immigration to Northern cities like New York and Chicago was also on the rise. The Irish and Italian immigrants who made these cities their homes also encountered police aggression and abuse. Dr. Muhammad explained that, unlike Blacks and non-European immigrants who do not have the option of passing for white, these communities were eventually accepted as part of white society and were eventually able to advance into the mainstream—earning key positions on the police force and in politics.

In 1965, the Hart-Celler Act (also known as the Immigration and Nationality Act) was passed, opening doors for mass immigration from Latin America, the Caribbean and Asia. Among those immigrants were Nilesh Vishwasrao’s family, which migrated in the mid-80s from India, following his paternal grandmother.

The practice, Dr. Muhammad insists, only seems new to us because stories of urban policing in the North were “drowned out by the naked, brutal terrorism in the South…”

Up until 1960, the neighborhood of Jackson heights had remained exclusively white (98.5%). Within five years of the Hart-Cellar Act, the percentage of white residents in the neighborhood dropped to 87.4%, and by 1990, more than half of Jackson Heights’ residents were foreign-born. It was around this time that the stretch down Roosevelt Avenue (comprised primarily of immigrant owned businesses) gained notoriety as “the cocaine capital of the U.S.” It is also here that a heavy police presence began to emerge with SQF encounters between residents and police occurring on a daily basis.

A decade ago, the U.S. Department of Justice examined perceptions of police among Jackson Heights’ ethnic communities, and found deep-seated mistrust of law enforcement among Latinos and Indians in particular. Today, national debates on immigration reform and post-9/11 surveillance continue to fuel feelings of marginalization.

Civil rights and non-profit communities continue to assess the human impact of these encounters in high-SQF neighborhoods like Jackson Heights. This past fall, the Vera Institute of Justice, a frequent advising institution to the NYPD on criminal justice reform, sought an answer to how SQFs affect young people’s development and their confidence in the justice system. The report, Coming of Age with Stop and Frisk, highlighted a unique difficulty in Jackson Heights. Residents were unwilling to talk about police practices, most likely because they feared exposure might subject them to legal consequences impacting their immigration status. Nilesh, who is not undocumented, is among the few to share his story of police harassment. He explained his parents’ only unwillingly interact with the police: “For that generation, calling the police is out of complete desperation. I think my father has called 9-1-1 maybe a handful of times.” In those days, Nilesh explained, they lived in another part of Queens and got robbed a lot, but he recalled that NYPD interventions were never much help.

Nilesh inherited some of his parent’s skepticism about police, but he’s also learned lessons about managing those interactions from others. He pulled again at his cigarette and explained tactics he’s learned to stay out of trouble with the cops.

“This is something an old mentor-type guy taught me, ‘when you’re hanging out with a group of friends, never be in a circle’—that sticks with me.”

He bristled recounting a time when he stood before two officers at the top of a staircase in the 74th Street station, shoeless. First, they took his ID. Then, they made him untuck his shirt. Roll down his sleeves. Take off his belt. Finally, they had him remove his footwear.

Through high school, Nilesh amassed a pocket Sun Tzu of tactics for maneuvering beat cops. Minimizing the appearance of threat was key. No circles, no ciphers, no hands in your pockets—nothing that would give the police any excuse “to slam you against a wall and break your fucking nose or something.” In essence: appear weak when you are strong.

He bristled recounting a time when he stood before two officers at the top of a staircase in the 74th Street station, shoeless. First, they took his ID. Then, they made him untuck his shirt. Roll down his sleeves. Take off his belt. Finally, they had him remove his footwear.

Before a gawking, rush-hour crowd, Nilesh kept a volley of expletives at bay and complied.

“You must have a real good hiding spot, huh?” they asked.

Mason-Dixon in Queens

In Jackson Heights, Junction Boulevard (what residents in nearby Corona traditionally referred to as the “Mason-Dixon line”) and Roosevelt Avenue, respectively, are focal points for police aggression. To the west of these boundaries lies the tree-lined Jackson Heights historic district and its prized housing stock—still owned primarily by white residents—and to their east and south, the immigrant enclaves in Elmhurst and the historically-black area of Corona.

For Blacks arriving to New York around the 1900s, city cops “polic[ed] the boundaries of whiteness” as Dr. Muhammad describes it. In Manhattan, the boundaries of Harlem and the now-defunct San Juan Hill were flash points, with police violence precipitating a number of urban rebellions throughout the 20th century, including the Fruit Riots.

“It’s all about—honestly—keeping us down and the rich, rich. The thing about Jackson Heights is, it’s super, super diverse, but there are territories,” he said, describing the various ethnic pockets around him: Asians around 73rd street, Latinos down Roosevelt Ave, and more affluent White communities in the historic district. To him, cops maneuver around these borders to enforce more than public safety. “A lot of people can’t differentiate some sort of security between a hierarchy. NYPD, they get a hierarchy.”

Nilesh re-enacted the stages of a stop and frisk he experienced months before. Asked how he felt towards the cops who frisked him, he replied “fuck you!” and laughed. As if on cue, a young Latina officer walked by, and admonished him playfully.

“Clean your mouth!” she barked, smiling.

Startled, Nilesh smiled back. He shrugged, feigning innocence–but exuding defiance. He’s not afraid of a little banter with cops once in a while, especially for expediency’s sake.

“It’s definitely an empowering feeling [to resist],” he explained.