The AAWW staff, interns, and fellows select their favorite books, music, film, and art from 2018.

December 17, 2018

Zena Agha, Margins Fellow

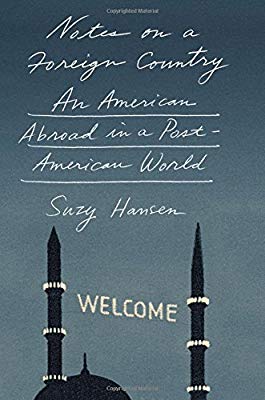

Notes on a Foreign Country by Suzy Hansen

I cannot recommend Notes on a Foreign Country enough, a brilliantly insightful nonfiction narration of an American abroad in Istanbul, Turkey. It explores the crippling realization that the whole world is intimately acquainted (and intimately scarred by) US imperialism while those in the US remain unaware of their existence. Covering swathes of the Arab and Muslim world, the foreign country, we come to realize, is America itself.

Hannah Bae, Open City Fellow

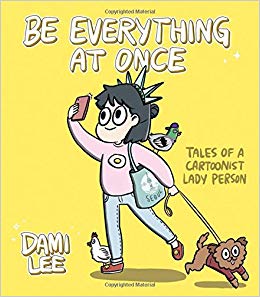

Be Everything at Once: Tales of a Cartoonist Lady Person by Dami Lee

What book would I recommend to my teenage self? An editor asked me that question this fall when I was speaking on a panel, and my answer was Be Everything At Once, the cartoonist Dami Lee’s debut collection of her wry four-panel comics.

Growing up as a Korean American, I never saw anything—films, literature or comics—that showed what it was like to be the product of two cultures in a contemporary, relatable way. Lee’s comics are an answer to that void, hilariously explaining the joys and confusions that come from being bilingual, from living out a transpacific youth, and from absorbing the best of American and Korean pop culture. I’ve been delighted to see everyone from my sexagenarian mother-in-law to my fellow Old Millennial pals laughing out loud while flipping through these candy-colored pages. But I’m especially excited to share Lee’s book with younger Asian American readers, who might see themselves on these pages and recognize that they, too, can make a go of a creative life filled with humor, honesty and color.

Hereditary, dir. Ari Aster

It seems like an unlikely choice, but this year, I’ve ended up recommending the horror movie Hereditary to a number of fellow writers grappling with complicated feelings about their parents and familial wrongs in their work. Sure, the film, starring an excellent, raw Toni Collette, contains enough fright and gore to meet the requirements of the genre (I let out at least one blood-curdling scream while watching in a theater). But where this story really excels is in its unraveling of domestic drama and the legacies of trauma that we pass on to future generations. This is a film about piecing together the mysteries of our parents’ lives and confronting the truth, as ugly as it may be. Deeply unsettling, its emotional truths linger long after any scares.

Johanna Dong, Editorial Intern

The Poppy War by R.F. Kuang

The Poppy War was one of 2018’s top fantasy books, the explosive debut of new author R.F. Kuang, who just graduated from university this year. Set in a fantasy world that mirrors East Asia—in fact, the war and genocide in the book is based on real accounts of the 1938 Rape of Nankin—it starts off as a fairly innocuous plot of a rural girl, Rin, being thrown into a new world of boarding school. The second half, however, is an utterly ruthless, brutally honest portrayal of the worst of humanity, ending with the question of whether acts of horrific retaliation can be redeemed.

The Machineries of Empire by Yoon Ha Lee

The final book in sci-fi author Yoon Ha Lee’s Machineries of Empire trilogy was released this past summer, and, in keeping with Lee’s endlessly innovative concepts, Revenant Gun took readers back to one of the main character’s past rather than picking up after the thrilling cliffhanger of second book Raven Stratagem. The series overall, set in a universe ruled by laws of mathematics, is one of the most unique and engaging works of contemporary science fiction I’ve read. These books include, in no particular order, machine sentience, revenants, brilliant immortals, and a deeply emotional green onion plant.

Pik-Shuen Fung, Margins Fellow

“The Kingdom” by Laurel Nakadate

For her solo exhibition, “The Kingdom,” artist Laurel Nakadate hired anonymous technicians to edit images of her newborn son onto images of her recently deceased mother, who never got to hold the baby. The resulting series of thirty-four photographs has an air of absurdity: here is her mother as a young woman on the beach with the baby in her lap, and there is her mother in wedding dress and veil with the baby on her arms. But even the most skilled of technicians failed to make it realistic; it was an impossible task from the start. Shown alongside other photographs, videos, and a sound installation, in which a payphone played the mother’s last voicemails through the receiver, “The Kingdom” was a haunting glimpse into what it meant for the artist to become a mother while losing her own, and her attempt to reconcile the two. In the futility of her gesture, I felt the magnitude of the artist’s grief and the relentlessness of her longing.

Freshwater by Akwaeke Emezi

“The first madness was that we were born, that they stuffed a god into a bag of skin.” So begins Akwaeke Emezi’s debut novel Freshwater, narrated by multiple spirits that all inhabit the same body. The body belongs to Ada, an ọgbanje: an Igbo spirit whose purpose is to torment the human mother by dying. We follow Ada from her birth as a baby girl in Nigeria to her painful college years across the ocean in Virginia. Written in lush, enigmatic prose, and held together in a form that manages to be at once fractured and fluid, Freshwater breaks through trauma, cruelty, and violence, to the freedom of embracing multiple realities, and the power of understanding one’s own place in the world.

Daniel Gross, Prisons Editor

Earlier this year, at the Third Coast International Audio Festival in Chicago, a producer named Phoebe Wang took the stage to accept the Best New Artist Award. Radio and podcast award ceremonies are usually like nerdy versions of the Oscars, hosted by podcasterati and full of tearful thanks for Moms who are watching the livestream.

Phoebe’s speech was different. She spoke of being hired at a time when she had zero audio experience. “I feel like I’m a product of a really intentional hire of a person of color,” she said. Then she called out organizations that fail to hire people of color, only to claim they’re trying their best. “I think that is total bullshit,” Phoebe told the audience. “What I really hear is, ‘We chose to spend our time and money on something that we decided was more important than hiring a person of color.’”

For a producer at the start of her career, this was gutsy. It was also what the audio world—which has much in common with the literary world—needed to hear. Phoebe’s speech earned a standing ovation. You can read and hear it here.

Tiffany Tran Le, Programs Assistant

Killing Eve

I unabashedly worship at the Church of Sandra Oh and join the scores of folks grateful to regularly witness Oh’s mastery again. Phoebe Waller-Bridge’s Killing Eve is the fiercely intelligent and hilarious spy series I never knew I needed. The procedural doesn’t bother to flirt with the binary of good and evil as we track a dizzying cat & mouse game between two brilliant femmes. It’s intoxicating to watch Eve and Villanelle spiral around each other, laser-sharp eyes fixed on the other. One is an impulsively renegade assassin and the other, a hungry desk lackey turned clumsy spy hellbent on finding an indiscriminate killer. They share boundless resourcefulness, wit, & even empathy all while, almost hilariously, finding creative satisfaction in the hunt for each other.

Be The Cowboy by Mitski

Mitski’s Be the Cowboy seemed like a gift for my oft neglected inner life in the rambling devastation of 2018. I have been listening to little else since the album’s release earlier, each time tenderly nodding to attendees of the vulnerability-themed party in this introvert’s body. I am listening to Be the Cowboy as I write this and I might as well be in a warmly lit blanket fort feeding s’mores to my friends anxiety, longing, insomnia, and nostalgia as we celebrate ourselves.

Ghost Of by Diana Khoi Nguyen

In Diana Khoi Nguyen’s poetry collection Ghost Of, she writes “If one has no brother, then one used to have a brother. There is, you see, no shortage of gain and loss.” Ghost Of is tenderly generous in its candid grieving as Nguyen works with figures drenched with loss: the absent figure of her brother in family photos, quietly extracted by her brother some time before he passed. In Ghost Of, mourning exists beyond linear time, and though its reach seems infinite, Nguyen’s control of its language is exact.

Jean Lee, Development Coordinator

These poems encapsulate the sentimentality, critical observation, and unparalleled force of poetry. In her poem “Power,” Audre Lorde says, “The difference between poetry and rhetoric / is being ready to kill / yourself / instead of your children.” It examines the injustice of a young black boy who was killed by a white policeman. “Power” is unique in its symbolism and intensity. Its first line speaks to the emotional power of poetry aside from syntactical and aesthetic beauty.

In her poem “Phnom Penh Diptych: Wet Season,” Jenny Xie writes, “Every day I drink Coca-Cola and write ad copy. / I’m in the business of multiplying needs. … / … Desire makes beggars out of each and every one of us. / Cavity that cannot close.” My mother once told me that wanting creates desperation. Xie offers a sharp analysis of how commodity culture manipulates to generate unnecessary needs, but she also speaks to something larger: desire itself. The desire to be and to belong. To close boundaries in familiar and unfamiliar places. Most of the lines end in a period, startling and severe, but carry so much weight with clear observations and all-consuming uncertainty. How could they be capped by something as stark as a definitive end? This poetic decision sparked an unrelenting whine that carried me through Jenny Xie’s ingenious book Eye Level.

Have you listened to Safiya Sinclair read her poem “Gospel of the Misunderstood”? The flow of imagery and Sinclair’s melodious voice encourages constant reading and listening. I just want to sit and listen to it on repeat, like a song after heartbreak. It speaks to the aching need to be beloved and seen. “Isn’t this love? To / walk hand in hand toward the humid dark, / enter the ghost web of the hungry, to consider some wants / were not meant to be understood. Some women.”

Grace Li, Development Intern

Cherry by Rina Sawayama

I went to see Rina Sawayama live earlier this fall, and she radiated so much confidence and energy, so unapologetically and contagiously. In her set before performing Cherry, a song that came out at the end of summer, she talked about how this was an ode towards her coming out as pansexual and a celebration of self-love and self-acceptance. To see an Asian American young woman, truly merging the personal and the political, and using music as a platform, is an experience that was truly inspirational.

“Someday I’ll Love Ocean Vuong” by Ocean Vuong

“Someday I’ll Love Ocean Vuong” is a poem that has stuck with me since it was first published in 2015. This year I read it again in a new light after the passing of a dear friend of mine, and it has struck me again for its vulnerability and sensitivity. Ocean Vuong writes about family history, memory, and selfhood with beautiful fluidity and nonchalance, and pushes us to spend time with his words with patience, awe and introspection, over and over again.

Jen Lue, Margins Fellow

The Age of Innocence by Edith Wharton

This summer I traveled back to China for the first time in eight years. On the fourteen-hour flight to Beijing I watched Scorsese’s adaptation of Wharton’s novel and I was so taken in by the story that I bought an English-language copy within the first week. During the six weeks I spent abroad I slept with Wharton’s book by my bedside every single night. Whenever I felt homesick for my life in New York, with all of its nuances and restrictions, Wharton’s novel anchored me.

In Newland Archer’s world, the system of punishment, repression and social control is so finely tuned that the characters easily inflict it upon themselves. This is pain-as-pleasure at its most refined. One of the most affecting questions that the novel raises for me is the way in which idealization of self and of other lays the groundwork for romantic love while also preventing it from ever being truly realized. As with much of my time in China, I never expected to be so moved.

Severance by Ling Ma

Ling Ma’s Severance explores the aftermath of a world immobilized by Shen Fever. The infected are unable to break out of their deadening routines—folding clothes, saying grace—repeating actions without thought until their physical bodies deteriorate. Severance’s protagonist Candace Chen, one of the uninfected, continues to work at her New York City publishing house in anticipation of an exorbitant final paycheck until conditions force her into the hands of a small group of fellow survivors.

The crux of the story rests in Candace’s attempts to wrestle with the emotional heat of the past while continuing to survive in the present. Her passages about visiting her father’s family in Fuzhou and the chapter in which Candace envisions her parents arriving in Salt Lake City in 1988 offer some of the most poignant depictions of immigrant love that I’ve read this year.

Yasmin Adele Majeed, Assistant Editor

Elaine Castillo’s queer immigrant romance America is Not the Heart and Brontez Purnell’s punk “non-memoir” Johnny Would You Love Me If My Dick Were Bigger hummed with a propulsive energy that pulled me through spring. Gina Apostol’s wry anti-colonial mystery novel Insurrecto perfectly fed into the knotted angst that I carried around all year. Days were always better when I received an email from Alvin Park’s “aspirin and honey,” the kind of Tinyletter that reads like a personal dispatch from a dear friend. And Sandi Tan’s surreal documentary Shirkers offered up a vision of a girlhood devoted to friendship and the guiltless joys of creative expression that I hope to take with me into the new year.

Jyothi Natarajan, Editorial Director

One Part Woman by Perumal Murugan, trans. Aniruddhan Vasudevan

One Part Woman by Perumal Murugan, trans. Aniruddhan Vasudevan

Banned in India for a period of time in 2015 after it came under fire from the Hindu Right, Perumal Murugan’s novel One Part Woman was translated and published in English earlier this fall in the US and left me wanting to read his entire body of work. The novel is set in a village in Tamil Nadu during British colonial rule of India, and its moving and memorable portrait of a marriage is sharpened by the way marriage becomes an object of control and public scrutiny, and how it works to uphold both gender-based oppression and caste.

“Survey of Caste in the United States” by Equality Labs

Caste and caste-based oppression permeates diasporic Indian communities, a fact that is often obfuscated by upper-caste dominated representations of the diaspora. Earlier this year, Equality Labs published a groundbreaking “Survey of Caste in the United States” that “presents the first evidence of caste discrimination in the US and helps to map the internal hegemonies within our communities. It also provides insight into how the South Asian community balances the experiences of living under white supremacy while replicating caste, anti-Dalitness, and anti-Blackness.” It’s a powerful, must-read document that centers the need to end both caste apartheid and white supremacy. I hope it spreads far and wide and recommend its use in classrooms, discussion groups, and beyond.

Ayesha Raees, Margins Fellow

Letters to a Young Poet by Rainer Maria Rilke

Rilke’s Letters felt almost like an address towards me. I find myself many times questioning the foundations that the creative industry exists on, its politics, its natures. In these convolutions, I often forget the very obvious, the human, the necessity of creating not for the world but ultimately for ourselves. 2018 was the first time where I existed without academic institutionalization and, amongst other creatives fresh out of college, struggled to find immediacy to the inevitable obstacles a youngling can face. These letters allowed me to step back to find a grounded core that we all possess and seldom fetch from. I recommend this collection wholeheartedly to anyone harboring difficulties with both the creative and the personal.

Ghost Of by Diana Khoi Nguyen

Ghost Of by Diana Khoi Nguyen doesn’t shy away from addressing a digression stemmed from loss while still being able to successfully instill an empathetic understanding in a reader. Nguyen addresses the Vietnam War, of a family’s physical displacement in the American landscape, and then dealing with a personal tragedy of losing a child, Nguyen’s brother, to a suicide. Nguyen’s poetry is successful in its contextual charge due to her choices in form. She experiments through cutting out abstract shapes from her poems to construct a silhouette which often represents the ghost of her deceased brother. These silhouettes represents a shard of a memory, a haunting of a past, a shadow of a being where the speaker feels, many times, as her own. What does it say about a future when the speaker at present feels the brother of the past is now her own embodiment? There is no rational explanation or a constructive manual of how grief is practiced and Ghost Of ensures every practice is valid and vital.

Kaitlin Rees, Asia Literary Editor

Creatures of Near Kingdoms by Zedeck Siew, prints by Sharon Chin

This year I’ve loved meeting more books from small presses based in Southeast Asia. Creatures of Near Kingdoms is a Malaysian bestiary micro-fiction written by Zedeck Siew with lino prints by Sharon Chin. The book is a beautiful and creepy catalogue of the local flora and fauna of Port Dickson, Malaysia, where the writer and artist are based, and offers a sincere vision for writing an environment without taking from it.

Oceans of Longing by Sitor Situmorang, trans. Harry Aveling, Keith Foulcher, and Brian Russell Roberts

Oceans of Longing is a fascinating collection of prose by Sitor Situmorang (1924-2014), the prominent Indonesian writer of Batak ethnicity, translated into English by Brian Russell Roberts, Keith Foulcher, and Harry Aveling. Marking the transitional post-colonial period in Indonesia, each of the nine stories feels pregnant with something, a silence (never) at home in Northern Europe and Northern Sumatra alike.

You Will Always Be Someone From Somewhere Else by Dao Strom, trans. Ly Thuy Nguyen

You Will Always Be Someone From Somewhere Else (re)collects the poetry fragments of writer/artist/musician Dao Strom, and is translated into Vietnamese by Ly Thuy Nguyen. The book traces the negative spaces of storytelling and identity and (be)longing across an ocean of “memory’s memories” between Vietnam and Northwest USA, taking my breath with it.