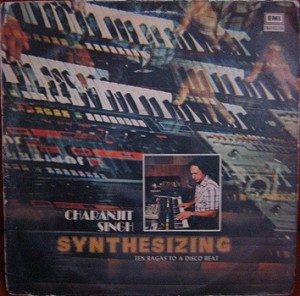

How Bollywood demo musician Charanjit Singh peered into the future of electronic music

July 31, 2014

Thirty years before Kanye dug up the Roland drum machine for 808s & Heartbreak, 10 years before Aphex Twin’s breakout studio album Selected Ambient Works 85–92, and five before Phuture released the 12-minute cornerstone of acid house music, “Acid Tracks,” a Bollywood demo musician named Charanjit Singh went into a basement in Mumbai and peered into the future of electronic music.

In 1982, Singh set aside four days of studio solitude with his new toys: the Roland TR (“Transistor Rhythm”)-808 drum machine—the same heard on Kanye’s Heartbreak and Marvin Gaye’s “Sexual Healing”—and a now-legendary Roland TB (“Transistor Bass”)-303, a bass generator and audio oscillator released just that year. With these, he grafted 1,500-year-old sliding raga scales onto the 4/4 disco beats that had just landed in India. The matter-of-factly-titled Synthesizing: Ten Ragas to a Disco Beat resulted. Among Acid House aficionados, this album is something like Schubert’s Unfinished Symphony and an early 1970s Afrika Bambaataa Bronx party: both a lost classic and an origin story.

But at the time of its release the album sold very few copies. Over the next 30 years it was drowned out by its would-be descendants, a group as diverse as DJ Frankie Knuckles, Daft Punk, and Lady Gaga. The synth sounds and fast 4/4 beats of House and Techno are now fueling the multi-billion dollar swath of the music industry that includes Electronic Dance Music and pop’s Euro-dance turn.

Thirty years on, Ten Ragas to a Disco Beat is almost incomprehensible. Not because it is hard to listen to: it is, like Acid House must be, mesmerizing. It’s just hard to believe that it came from its place and time. Singh is an alchemist, a missing link between Bollywood, techno, disco, and Indian classical music. As critic Geeta Dayal pointed out, the “303 ends up being perfect for the slithery glissandos in Indian music, the sliding between one note and the next.” Instruments like the shehnai and veena, spun through his Roland equipment, become wild, futurist electronic noise. And his collaborations with “Disco King” Bappi Lahiri, the legendary Bollywood composer and music director, told him that this was a dance craze with staying power. American DJs were already proclaiming the death of disco, but under Bappi’s Bollywood, it was the hot new trend.

Ten Ragas lacks the strungout, revel-in-our-carefree-youth of so much EDM. This music makes you want to motorcycle down a neon-lit alley in Mumbai, to inhabit a frantic, 8-bit Atari game. Perhaps if Kraftwerk had followed The Beatles’ lead and spent a month or two in India, or if the Bollywood composing duo Shankar Jaikishan hung around Chicago warehouse clubs in the 1980s, they might have produced something in the same realm.

And what if this album did become, as Singh surely hoped, the definitive touchstone of Acid House? The always-behind West wouldn’t have waited for M.I.A.’s “Jimmy” to introduce us to the Bollywood classic Disco Dancer (released in the same year as Ten Ragas). DJ David Guetta would be studying the differences between a bhairav and a yaman raga. Mumbai could have been EDM’s Mecca.

In 2010, Ten Ragas was re-released on the label Bombay Connection. The release brought a wider audience, recognition as a cult classic, and a flurry of tour requests. Singh, now 73 years old, is leaving his modest home in Mumbai for a rare international tour, his second since the release. His promoters have promised that he will be using original Roland 303 and 808 machines, not the shiny macbooks that dominate the house circuit.

Last weekend, Singh made his New York debut at Lincoln Center Out of Doors. This weekend, he plays at the Body Actualized Center in Bushwick and MoMA PS1 Warm Up series, where he will probably have a good 40-50 years over the average audience member. Fitting for music that jars your sense of time and place. When Ten Ragas was re-released, many wondered if it was a hoax: critics could not believe such an album slipped by them all these years, while others called it “antique futurism.” A good track synchronizes bodies in a room; Ten Ragas does the same, but from a Bollywood basement studio, thirty years in the past.