You couldn’t claim that you were lost. The footsteps of your comrades dragged you sharply back into the present, no wavering possible.

August 3, 2020

1

It wasn’t something one could know in advance, her life inside the jungle. Yet, the jungle provided a road out that one could track, through the village that had settled upon its borders.

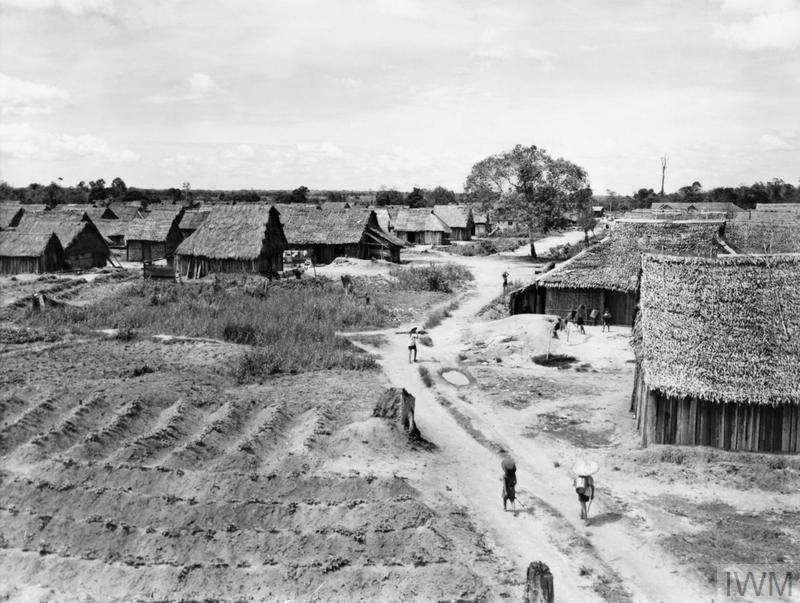

You are all the same. That common refrain, the only way they were seen by the colonizers. The color of their skin had been marked to make them legible. Different colors connected, from their yellow skin to the red star of their flags, and then the white zones where they were moved into, where they would be free, while they were put under watch by those with guns and fenced up like herded swine.

How would one ask the question: Were you afraid? How did it feel when they burned down your house?

And then: Who was involved? Did they speak to you, give you a reason?

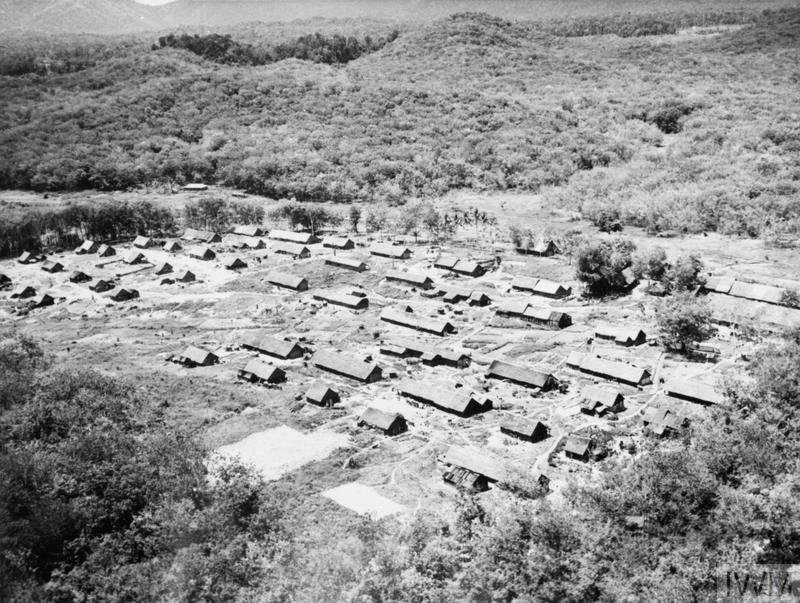

I had started observing these village camps, through wide-angled pictures that arranged them in distinct squares. I didn’t know if she still stayed in one of these places, but she had wanted to meet in the compound of a coffee shop that had grown out of the camp. We sat underneath a thatched attap roof waiting for the merciless rain to evaporate, the hills in the distance hazy, out of focus.

I was surprised she hadn’t been to this part of the village before. It was mentioned more than once in the stories I had read. When we first met, she evaded my questions about her writing, preferring to talk about the numerous tales she had overheard as a child; details about the jungle she had collected, like specimens of mushrooms that grew deep within the green. She passed me this snippet, which she would continue in her letters:

The flower grew unexpectedly, a blue orchid on an abandoned wooden plank. I had been searching for traces of life – the ant and butterfly that co-existed, a partnership that could only appear in these circumstances – and the other creatures and insects that lived within.

I thought of the wildlife I had encountered, when I entered the jungle with her the first time. The leaves that were alive, caught within the echoes of crickets which had no audience but the still air; the teeming settlements of small creatures borne within its borders; the harshness of the land on those who had stayed.

According to her letter, she had entered the jungle out of curiosity. At the height of the communist struggle, it had been fashionable to be progressive, and spend one’s youth mulling over how one could contribute to the betterment of the people. Yet it was also possible to be attracted by the flora and fauna inside, and unwittingly become part of the landscape where one would be confined by the British. Entering to escape, you would then come to know its every detail, an imaginary world where things were separate from the usual path of life.

I found it impossible to believe in the poetry of this place, where the overgrown leaves and canopies almost obscured the sun. Daytime became night when the insects became louder, the occasional wild animal screeching in the expanse, and then fading away like a wave.

To think that others, like you, were also secretly in here…

2

Within the jungle there was a pervasive smell. A peculiar muskiness, borne of humidity that hadn’t yet settled after the rain. Shredded leaves, or a broken branch beneath one’s foot, could signal danger everywhere. Yet she was able to navigate the treacherous rocks and onrushing streams with ease, sensitive in her steps to the nuance of the slippery path.

You couldn’t claim that you were lost. The footsteps of your comrades dragged you sharply back into the present, no wavering possible. There was no way of being alone, and yet it was possible to feel alone. As she stood in front of a tangle of tree and bark, I suddenly imagined her looking for the butterflies she wrote about, while hoisting a gun and wearing a soiled cap. It struck me as futile to follow these small insects that would take flight and leave at any moment, without cause or reason. Yet, her spritely movements through the jungle suggested an intimacy with the land, which I couldn’t match.

In her house, I saw a framed landscape. Brown wood hung around a white piece of calligraphic paper; its thin sheet painted on by brush strokes that hinted at vast hills. At first, she had written, it was easy to believe that one belonged inside the jungle, in a grand cavern of dreams that stood to be fulfilled through human effort. But then came a loneliness she described as creeping, like snails you would step on unintentionally.

Sometimes, it was hard to differentiate the animals from humans, as they dwelled within the dark, only lit by flares released in a hasty call to arms. Sometimes, your comrades didn’t respond to your shouts, because the path they took to reach the next mountain had been cut off by the Gurkhas. Surrounded, a comrade had started humming an old Chinese tune about the ancient hills, distant yet claustrophobic, as if one could never really leave…

The jungle was always that kind of place for me. I had imagined it from her writings, even before I made my pilgrimage to see the dense thickets. She knew how to survive within this trap-filled place – one misstep, and you would be swept away by the rivers. No one, not even those who wore the right colors, could fight the current; true equality was through fear of the jungle. She moved like a seasoned guerilla, who had seen her share of bodies within the unforgiving green.

When we returned from the jungle, she started speaking about him. Her face, inscrutable before, had suddenly shown a flicker of recognition, a suppressed emotion that was between anger and longing.

He was not an unreasonable man. He had moved her entire family into the camps – an unspeakable incident which later, she pointed out, had become a mythical origin for people of her ilk, those who had been forced to enter the fences and barricades, and lived in these sites the rest of their lives. The elderly remembered this through their rituals – some offerings to their ancestral homes, remnants of the past before they had suddenly been uprooted from their lands and livelihoods. This past was unknown to him, and she herself had only heard about it in passing. She had never been to the early settlements, though in the jungle she once met someone who claimed to have lived there, before everything had been razed and burned to the ground.

Later, the reasonable man gave her a book, written in his language. It was in that language – what people like her called the devil people’s language – where one was sentenced for crimes, and they passed harsh, unspeakable judgments, which led to one’s disappearance, for a short time or forever. If one were called to attend this trial, you prayed they didn’t separate you from your family, and send you away within hours without a final goodbye. Others escaped before being dragged to these sites, where their fates would be determined by the stroke of a pen.

It was terrifying to encounter this machinery. Even then, she understood she needed this language to escape. Those on the other side of the fence spoke words that got things done, a magic more swift than the Buddhist prayers she grew up with. Their words had a sharp edge, directed towards the construction of new houses, the removal of weeds, and the excavation of jungles she once entered with her father. She would have to forget what she had been brought up to believe, to extinguish her childhood and become less of a threat. Enemies are everywhere…she started writing in this new script, acting out everyday life as if it were a book she was composing. The days of the jungle and her childhood became only words. She forgot how her world felt like, the moment it was written into his.

3

Mother said: to escape, you must first learn what doors were available. Only then could you begin to see what life was like, outside of the jungle.

We lived on the frontiers of the land, where we were condemned to wake at four, leave at six, and be groped on our way out of the fences. We were hungry while we worked the rubber trees, always in fear of gunshots. The devil people would sometimes smile at you – a sanctimonious greeting, because they kept guns in their pockets. It was a peaceful way to grow up, they’d probably say now. But it was also where I learned that the world could be such a limiting place.

One day, I looked at myself in the mirror, and realized that I looked nothing like the other children in the village. I was a shade darker and bigger, things they never ceased to comment on when they passed by me.

I knew I was destined to leave. In the jungle, we found respite only within the plantations. Hungry, worn-out, that was the only time when we weren’t watched by the devil people. Other pairs of eyes roamed whenever you thought you were alone, but we got used to them. They belonged to hungry ghosts who had spent too much time in the jungle, and you would see traces of them, little men obscured by the thickets, impossibly thin from the great famine.

One of them liked to come by the house around noon, with a friendly smile on his face. He acted as if he had already known you, only waiting for the chance to meet. Each time, he brought a pair of plants from the jungle. Curious, I had asked to keep them; he agreed, but with one condition: that I would water them. Because, as he put it, the jungle was death.

I hadn’t known death. All I had known before was how to catch the insects that didn’t seem confined by our fences. They could hop in and out without rules, unlike our cordoned lives. Those with guns could act as they pleased, while we were always on the lookout for unexpected events and sudden activity.

Anything was possible. One time they brandished army knives the size of guns, hovering at the fences menacingly; one of them looked on from his guard post with murderous intent…the rumors quickly spread: here were the communists, they had arrived at our border, and it was time to defend our land. I had been afraid to leave the house that day, and ended up staying inside our wooden shack while mother went out to tap rubber as usual.

Later, we realized that the British soldiers had been doing some gardening along the fences. Apparently, the wild orchids had become overgrowths and entered the village illegally, and they had taken the liberty to put things in order.

The language of the orchids – could they hear them? Or had the orchids, too, been silenced by the fences? Sometimes I wondered how these pale-faced men felt in the sun, where they clearly did not belong, and yet had to serve as guard and protector at the same time. They spoke to us infrequently, their accents a strange yelp, like young boys in the heat. At that moment, the British sounded alien to me, and I wondered if the orchids would speak to them, like they spoke to me.

She still lived near the jungle. Ten years on, I found only scrap paper everywhere – jottings, scribblings, and sketches that had been abandoned. Ainaa, they were signed. The banyan trees swayed thinly outside the windowsills. A few entries, a few books, preserved in the house of she who lived alone. But she was nowhere to be seen.

It had never been clear to me why she adopted this name. Maybe it was because she had lived here for a long time, and wanted a pseudonym as a mark of her own history. Ainaa, a name of ambiguous origin, foreign to all these proximate settlements in the country – the Malay, Chinese, Indian, Japanese and British that had been clumped together through a historical accident. Leafing through the sketches left behind, I realized she had moved here when she was seven. Early on, she had written:

The butterflies have come again. I didn’t have to go to the jungle this time.

It was still green when I left; they burnt down all the houses.

I didn’t meet him until this year. He had been in our village before.

In one of her published stories, Ainaa had been given away at birth, a child of the nearby Malay kampung which name she no longer knew how to pronounce. She could have returned after the war, but she had forgotten how to speak the language of the mosque, the azan that regularly echoed in the rubber plantations at dawn, when she followed her adopted Chinese mother into the unending rows of trees to be tapped. Their sap filled the buckets she would carry with her small shoulders, as her mother silently made a wound in the tree bark. The sun rose at six thirty sharp every day, and by the time they reached the fifth row of trees, she would begin to feel her stomach growling, and they would have no food…

This was a scenario that appeared repeatedly in her writings, and with each version, the scene became more detailed. After Ainaa encountered the red-haired foreigners (once, in an inopportune moment hiding behind the trees), she started referring to them as the devil people. They wore strange uniforms, and looked like they had been thrown into a metal cauldron, scorched and burnt by the unrelenting sun. Pale-faced, they stood out underneath the red and yellow rays that filled the land from dawn to dusk, carrying their black batons and snake-snouted guns around as if protection against the local elements. Her own skin was dark, and she would smile to herself when he mentioned the weather to her, a mocking smile as she recalled her first impressions of these fair-weathered people.

How does one live in the jungle? This was a question they asked, even while skirting its edges, like dogs attracted to meat within a cage. Eventually some of them would enter to hunt for the reds, as was their modus operandi in these faraway places. This was recorded in their flickering black-and-white films, the protagonists inevitably pale-skinned men. In these reels, one would catch a glimpse of their eyes, once they completed their rustling of foliage, with purpose befitting those who had been brought in from other parts of the Empire. You would see them whole, as opposed to the communists who were bloodied and cowering, dragged out into the daylight as if a skinned cat to be dried.

Through these encounters, the devil people gradually became part of the jungle, their strange accents overheard by the hungry ghosts, who feared detection and took them to be a sign of danger. Ainaa hid herself from both sides, preferring to observe the exchange of bullets that seemed to follow them everywhere. One time, she saw a bloodied man plant himself against a tree trunk, and she had sketched a poem about the banyan trees, of which she now only remembered the lines:

Did you see the man stuck in between the trees?

half-eaten, a man

like an animal…

4

I never learned how to cut the trees. I could hear the plants whispering in the wind, when I was alone. Later, I realized that the jungle eluded your writing, as it consumed you through sheer moisture, and left you exhausted after the humidity soaked through your words. Everything would disappear. Even the devils wrote that the jungle held no sympathy, after they had left and returned to their lands. But we had lived in different worlds, barely intersecting except through gunfire. They laughed as they sat around cleaning the dark barrels of their guns, playing at shooting some ghosts…

The first time I visited, I hadn’t understood why she had returned. The surroundings were chock-full of weeds and insatiable mosquitoes that stung you at will, interested in extracting as much fresh blood as possible from a newcomer. I had always been poorly equipped to handle the tropics; my own predilection for the cold, only reinforced by my time away from the heat, in the northern climes that I had been sent to as a child. I later understood that this was the wrong way to approach a place tied to the lives and deaths of real people, their bones buried beneath the soil without a sign or marker.

There was a time when she knew the jungle better, she had told me. It wasn’t something people here would admit to anymore, as they had been forced to leave the past behind, once the last of the hiding spots inside had been dismantled. She knew of those who didn’t want to leave, and never returned to their past lives before the jungle. They were forbidden to cross the border that now existed between tree and tree; an invisible regime of checks, stamps, licenses, when before you could have plucked the fruit on the tree without remorse, if you had your gun with you. Yet her own return had been quiet, reuniting her with her mother’s house, a mango tree flowering outside.

There were other published books about the camps, though she had been unhappy about the way they folded her childhood into the war, as if nothing else had existed then. In her letters to me, which were always stamped with an image of an orchid, she shared extracts from some of these books. Yet, she was prone to sudden outbursts about the inadequacy of this or that writer who had, in her eyes, failed to understand the jungle. There was only one author who she respected, a woman by the name of Han, who nonetheless had been forgotten by now. I was vaguely aware of that book, though as a degenerate youth abroad I had mostly neglected local writing.

She had been living in the city, when the tsunami had hit, and wiped out most of the remaining settlements near the jungle; this had made international news. After that, she had returned to where she had been as a child, to these camp-turned-villages where, it was rumored, ghosts still roamed, and would appear if you weren’t careful about what you said.

The rivers have disappeared, she wrote. We once had these problems too, when they decided to move us into the camps. Ironically, after the catastrophe, her village had been designated a water reserve. The surroundings grew back slightly into what she had remembered, even if they were now dotted with debris. But she had returned alone, like the early Chinese pioneers who found the land before them full of toil but also opportunity, to plant their own trees and establish new settlements. This was all old history that I had read once, which she liked to insert in her letters…

We had played near the trees growing up, and knew each clearing, each branch. There had been stories of places which had not been mapped out by anyone yet – the true wilderness, where if you entered you would disappear. We set aside a few moments each morning to burn the joss sticks, the flurry of paper money swirling, blown about by the gusts of wind that always seemed to accompany the ritual. I remembered, once, my mother had asked me to join her in the burning, and my eyes had singed from the scattered ash.

We knew they would not return. Yet, we never compromised on this part of the morning, even after we were moved. The ritual at seven, the same slight song that we mouthed silently, afraid to be overheard. The jungle seemed more alive than ever then. We were calling out to it, to those who had decided in their momentary putsch, to make of it a home.

I imagined I would never see him again.

After the resettlement, it was no longer a place of childhood whimsy and innocence. In the stories of those who knew the jungle as sacred – villagers who I encountered while looking for her – there were areas you would not enter, even though they cycled into its dark canopies to tap the rubber plants that would bleed and seep and cry. Where the sunlight was blotted out, you would see giant ants that had been left alone for millennia, hear the cries of fanged boars that were larger than their human prey, and stumble upon darting men-trees who whistled like fairies, who could snatch your life at one fateful moment…

The villagers had said to never enter, lest you found yourself isolated and hungry, having to bargain with those who made it their work to hide within green thickets, to hunt anyone who dared to enter. Wu hu ai zai, they wailed, an ancient lament that could only be translated as the sound of grief. Yet, their joss sticks burned for those who did not return after the amnesty had been announced, a generation of them lost, commemorated only by the trumpet sounds that accompanied the funeral processions. They all knew someone inside.

5

We had been prepared to carry out whatever was necessary, to give our lives as if they were tribute to a new emperor. Except here was not an impersonal god, but the People who were sovereign, and would understand our struggle…it was not always possible to understand their wishes, and some of us knew that the solution was to interpret their wishes for them. One might ask what the point was to fight such a war, but wars happened for reasons less noble. If one had known the feeling of being inside the jungle, perhaps one would understand why we deigned to form another government…out of necessity and idealism to make things happen here, in this place forsaken by the gods…

Her letters had stopped arriving at this crucial juncture, where the descendants of the villagers had started a new war, unaided, against the state which had control of weapons and the narrative – the moving images, radio broadcasts and posters that featured multiple languages and skull signs, to convince you to choose life instead of death, the city instead of the jungle. Yet this second war had ended as quickly as it had started, and she was one of its survivors.

She had left the scene at the point where she, too, momentarily held the weapons that would free the land. This was where, I thought, I could pick up my own story, and continue hers…

My mother had told me these stories, to justify my father’s disappearance. All this while, I hadn’t known how I would react if I encountered him in the dark of the green. Their eyes still seemed to be watching us, years after the devils had been consumed by the jungle. Most of the fighters had been accounted for, in the dark of the camps that were set up to let them leave. But he had stayed on in the jungle alone. The rest of them filed out in line and found ways to leave, as the world outside began to forget about their past, a past they had held on for so many years.

No one expected him to kill himself. Yet this was what the messenger said he had done, during a time of peace, when those who left the jungle had settled in other villages that were named as such. The Peace and Friendship Villages. Even those places did not survive the cull of nature later. We were to pay for snapping the orchids, their unheard sounds returning like appendages to reclaim the land. There was no real peace for those who had been moved, whose daily rituals were designated as threat, as dangerous as those who possessed guns. Perhaps the devils imagined we would fry bullets like we did the fish we caught in the slipstream of the tin mines; or they thought our livelihoods were guaranteed by slipping food and drink to the jungle ghosts.

They had written in their books that we needed to be protected. At first, I had thought it plausible that we who had no guns, and little inclination to fight, would need those with guns and jeeps and hats to take care of the camps. They seemed vigilant, always on the lookout for dangers unknown. He, a bespectacled man who visited us once every few weeks, brought with him armfuls of delicacies we had never seen before. The candy, soft drinks, bright and cheery wrappers – most of us had never seen anything of that sort, adult and children included. He seemed young, barely past twenty-five; yet, the elders assented to him, as he entered our lives in a chauffeured jeep, usually with another uniformed man – one of us, I thought, except he was now dressed like the devils.

Mother told me their forked tongues would prove to be our savior. The white-robed men and women held classes in the old building with the cross, and we were encouraged to attend every weekend, to help us help ourselves. The new country was coming, where everyone could be free, saved from the benighted ages when we were forced to clump together unhappily in the jungle like a herd of malnourished pigs, looking for the next seed that would never come…

I wondered how she had changed after entering the jungle. Had she been driven by a dream to redress the record, to show those who were watching that we, too, could run the world? It was hard not to be tempted by the jungle that called out to you, punctuated by loose gunfire and low-grade battles. This was what the colonizers had once called “banditry,” concealing what had been a bitter war of hunger and death. As if they were playing at adventure inside. As if they had gone in, desiring to be characters in a story…

6

Around the house, a strange idyll had set in, even with all the mud torn up by recent storms. You could see the sun from here, a glimpse of its faint rays refracted at just the right angle, unlike most places where it was hidden away by years of wartime smog.

She had probably returned to the original sites in the jungle, the tents and camps that would be moved at an instance, when the British decided to sweep in. I imagined she wanted to rediscover her village before there were camps and guns, before the fences had been constructed. She had written that the jungle was a mystery to her, a place where she had vague recollections of playing as a child, where her father had supposedly brought her and then was never to be seen.

The missionaries had adopted me then, and I had started living outside the fences. But I knew that mother was still behind the fences, waiting. Sometimes the jungle dwellers would return without words. All that was uttered was the usual, “We have eaten.” I know this because he came back once in the midnight, his hair crumpled and shirt torn apart, the dirt on his hair still fresh, as if he had just been scrounging underground. He came in through the back door and headed straight to the table where mother laid out the rice and vegetables, sweet potato leaves and porridge. Before the night was over, he had left, with only the plates left behind, the occasional stalk of leafy green simmering in the brown soy sauce.

He was a ghost our house had adopted. A dirty, ragged ghost who we never spoke of. I could only imagine, in his mute state, that he had eaten the joss sticks that we burned. The ashes in the wind, reaching wherever they had last been seen, rendering them silent, without a past.

My mother told me she had then entered the jungle in the early dawn, only to find a wild boar making tracks in a strange pattern as it moaned, injured. She had not dared to approach it, yet it had crawled away by the time she finished her rounds. The next day, it reappeared, slumped against a tree trunk. Even from afar she could sense the animal’s strange energy, the cold air surrounding it in this humid place. As if placed there by the gods, it only knew how to return to its spot.

Return – if that was the right word. Once you entered the jungle, it wasn’t clear if you had left your original place, or simply discovered where you ought to have been all along.

Father, you have returned, she wrote, and left me behind. She had been a child when he had gone into the jungle. Her letters had been delivered to no one, written more in hope than intended for an actual recipient. But our correspondence meant that I alone knew this story – Ainaa.

The joss sticks she kept lighting, long after everyone had left, were running out. An orchid hung in the corner of the room, as if it had emerged from her letters. I now understood it was my fate to enter the jungle.

I returned as a wandering ghost who had missed the past, having perished in the first encounters with the devil people, in the banyan tree. Picking up a loose brush on the floor, I started to write…