Ali Najmi, the contender to represent one of the largest South Asian enclaves in NYC, talks about Glen Oaks, the Sikh gurdwaras, and taxi drivers.

July 8, 2015

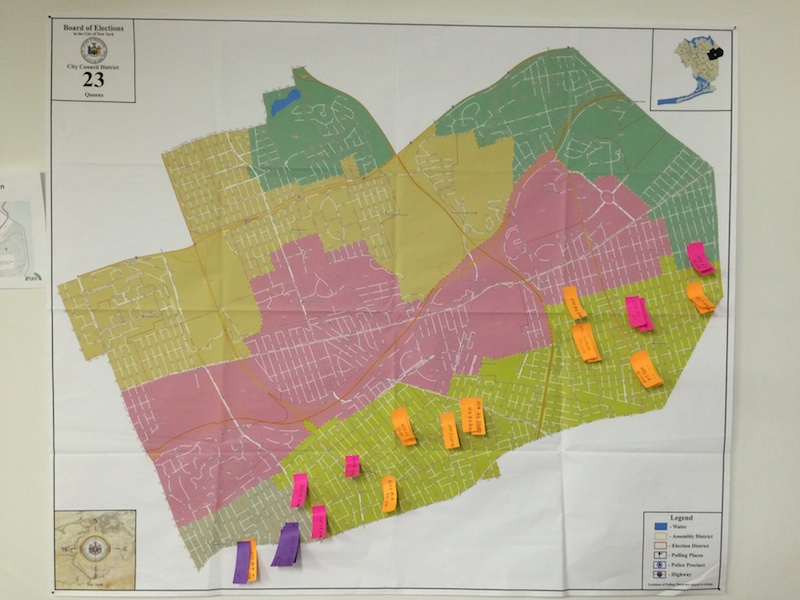

“This is a tale of two districts—a more homogenous one above Union Turnpike and a more diverse one below it,” explains 29-year-old Mohammed Khan as he traces the street with his finger on a giant map of City Council District 23. The map covers half of a wall in Ali Najmi’s City Council campaign office, where Mohammed has been working as Ali’s campaign manager. “This area is all white,” he says as he points to one region. “Lots of brown folks here and here,” as he points to other neighborhoods on the map.

Ali Najmi’s makeshift campaign headquarters are in the basement of a Korean Church in eastern Queens, far from any NYC subway line. To get here, I hopped on the Long Island Rail Road to Queens Village and biked the rest of the way. The 30-foot by 40-foot, fluorescent-lit room has a few plastic folding tables set up as desks, cluttered with stacks of “Vote for Ali” glossy brochures and green voter petition forms along with a giant family pack of Doritos and Fritos.

“We’re pretty much here from 10:30 am to 9:00 pm, seven days a week right now,” Mohammed, who is from Jamaica, Queens, tells me. The white building, which looks like a small house, sits on Winchester Avenue in Bellerose, Queens. Thirsty after my long journey to the office, I step out to buy some water and walk toward Hillside Avenue, as per Mohammed’s instructions. I pass several suburban-feeling side streets lined with single family homes—some quite large—with front yard lawns. The neighborhood feels far from the New York City—and even the Queens—I know. Miraculously, there is a bodega on the corner of Hillside Avenue next door to “Lahori Kebab and Grill” and “Szechuan Kitchen.” Feeling more in my element, I walk in to find a desi shopkeeper speaking Hindi to a few other men in the store.

Bellerose was formerly a mostly white, middle class neighborhood until the early 1990s, when South Asians who had the means began moving there and to the surrounding areas en masse. Thirty-year-old Ali Najmi was born and raised in a nearby neighborhood called Glen Oaks. His parents, who migrated from Karachi, Pakistan in the early 1980s, were among the first wave of South Asian immigrants to settle in the neighborhood, which borders Nassau county. In his lifetime, he has seen the area become one of the biggest South Asian enclaves in New York City. Ali explains, “You come to my neighborhood because the school district is good, the houses are nice. This is the sort of most American Pie neighborhood you can find in NYC without crossing into Long Island.” According to the latest census figures, Asians — mostly South Asians — now make up 40 percent of the area’s population.

Rapid demographic shifts can often be met with backlash. A 2009 New York Times article highlighted the resentment that some longtime white residents of Bellerose felt about the changes:

But as they [the Augugliaros, longtime residents of Bellerose] sat in their living room, they expressed unhappiness with what they see as other undesirable changes in the neighborhood: street vendors selling halal gyros; traffic congestion near the Indian and Pakistani grocery stores on Hillside Avenue; newly created mini-mansions, many of them occupied by extended South Asian families.

“They’re turning the neighborhood into a third-world country,” Mr. Augugliaro said. “We don’t want it over here to look like Richmond Hill or Jackson Heights,” he added, speaking of Queens neighborhoods with sizable South Asian populations.

Ali says, “In any neighborhood when it changes that dramatically, there’s gonna be some tension. So some of those things have come up, but overall it’s a very harmonious neighborhood, a diverse neighborhood.”

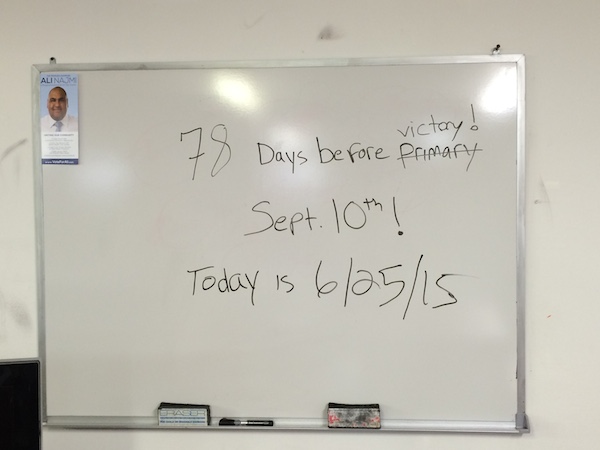

And it’s a diverse neighborhood that Ali wants to represent in city government. He is currently in the petition phase of his first electoral campaign with hopes of winning the Democratic primary on September 10th and becoming New York City’s first South Asian elected legislator. A few days after my visit to his campaign office, I sat down with Ali over a cup of chai in my Brooklyn kitchen to discuss his childhood in Queens, his campaign, and his hopes for the future of his district.

What was it like growing up in Glen Oaks?

I was born in the district, I left for college [at Oberlin], and I came back. I’ve been here my whole life. Overall it was great growing up in Glen Oaks. It’s a mixed district, but the parts of the district that I’m from—Glen Oaks, Floral Park, Bellerose—probably have the highest concentrations of South Asians—and more importantly South Asian voters—than any other part of the city.

As a community, we were recognized as a big South Asian enclave by the late 1990s. If you look at certain commercial corridors like Hillside Avenue between 249th Street and the [Nassau] county line, it’s like all Indian stuff. On that strip, we have a Patel Brothers, an Apna Bazaar, another grocery store I forgot the name of, competing Usha Foods—the real Usha and the one that was bought or whatever—we have a mandir on that block, and two gurdwaras, not on that strip but in that area.

Where are most of the South Asians in the neighborhood from? Are there any particular regions or religious groups that are the most predominant?

I’m proud to say that this is probably the most diverse South Asian neighborhood in the city. The Sikhs are the most visible, and they make up a large number. But there are a lot of North Indian Hindus, too. Floral Park has the highest concentration of Malayali people [from Kerala] in North America. A lot of my friends growing up were Malus, as we’d call them affectionately. And all their moms were nurses, so we’d go hang out at their houses at night because their moms weren’t home. And there’s a big Muslim community too—lots of Pakistani and Bengali people. We have a couple of masjids in the district. The neighborhood is an eclectic mix of South Asia.

Aside from the diversity, how is your neighborhood different from other South Asian neighborhoods in the city?

It has a higher income group. So you could distinguish this neighborhood from Richmond Hill or even Jamaica Hills purely on medium income. People are a little more well to do than in other South Asian neighborhoods—maybe not as much as Long Island folks, but city-wide, definitely.

They also have higher citizenship rates, and therefore the most active voters. In recent Democratic primaries that have been held that overlap with this council district, about 20 percent of voters have been South Asian. Richmond Hill doesn’t vote enough—I’ve looked at the data.

What was your scene growing up in Queens? Where did you hang out?

As a teenager, I hung out with my good friend Himanshu Suri [aka Heems of the band Das Racist]. We had a little scene in Bellerose. Most of our crew were South Asian kids from this area. There was not much to do, honestly. The scene was trying to do good in school and find some place where our parents would let us go out. We hung out in people’s homes and out on my stoop.

I think people in New York City grow up really fast, but that’s not really the scene in Bellerose. We were all overachievers in schools, and we were all on our way to good colleges. Some of these kids turned out to be huge professional success stories. We were under the eye of our parents a lot, and we didn’t have much to do. Heems and I would just sit on my stoop and kind of pontificate on ideas all day, you know what I mean? It was a lot of just chilling.

What inspired you to become politically active?

I think that in the latter part of high school and the early part of college, I started doing a lot of reading—and really learning about inequity. I got interested in social justice, and I kept looking for answers. When I got to college, I started really following national politics and reading and taking classes on organizing movements, like the civil rights movements. And it sort of clicked to me—if you can organize people and get them to vote a certain way, you can make changes happen.

As soon as I got back from college, I came home and saw all these things I didn’t like—some of these things still haven’t been fixed. I saw a lack of institutional respect for immigrant communities that you could really feel on the ground. I just wanted my community to be respected, and I knew we wouldn’t be respected unless we voted. So I got involved in the Democratic Club and the local political scene and elections. The first elections I really got involved in were in 2008—the Obama race but also the local state senate race. And ever since then I’ve worked on elections. I worked for Council Member Mark Weprin of the 23rd District for two years as his legislative director in City Hall and got to see how things work there. One thing that continuously held true and kept getting more and more validated was [the importance of] people being organized as voters and going out to vote on election day.

What campaigns or politicians have been an inspiration to you?

John Liu has been a huge inspiration to me. I know there was a shadow cast on him because of some of his campaign finance filings during his mayoral campaign, but if you just take that out of it, John Liu is a kid from Queens who carried the political reputation of the Chinese American—and Asian American—community on his back. There are more Chinese triple prime Dems—people who voted in the last three primaries—because of John Liu. He built a base of people and built a coalition of people of color all over the city to win his comptroller race. He’s been an inspiration to me, just to see him come out of Queens—a similar narrative, similar story, different neighborhood—and rise up and get immense attention for his community and bring immense resources to his district.

I know you have a background in organizing. We crossed paths years ago when you were working with SEVA in Richmond Hill. What drew you to that work and community?

I’m not an active member of SEVA anymore but I learned organizing through that group, which does organizing in immigrant communities in Richmond Hill. For me, the Sikh community is such an important community. Being a Muslim kid, a Pakistani kid, it kind of didn’t make sense that I was in the gurdwara so much. But I was, and not just one—a few. And it was awesome. We’re all South Asians, but… people don’t really go to each other’s religious institutions. I was the only random Muslim guy running around the gurdwaras. And in the beginning it was a little weird, but then I became fully accepted. “Of course Ali’s at the kabaddi tournament, of course Ali’s at the nagar kirtan, of course Ali’s at the Sikh Day Parade.” I loved it, and I learned so much from it.

I got involved in SEVA when I was 24. We did this big redistricting campaign. Probably one of my biggest political accomplishments is getting a district that’s drawn to empower South Asians—the Assembly district in Richomnd Hill is 40 percent South Asian now.

What do you make of the fact that there has never been a South Asian legislator in New York City?

It’s a huge surprise to a lot of people. The desire to have a South Asian legislator is a big motivating force in my base. You have South Asian elected officials in parts of the country where there are very few South Asians… In Louisiana and South Carolina, they had to become less South Asian there to win [laughs]. They’re winning in areas where there are no South Asians. In a city that boasts the greatest number of South Asians, why isn’t there one here?

I think that South Asians have been up until now an emerging community. The difference now is, we have emerged. We have a second generation that is hitting our 30s, and we kinda know the game, we know the system, we’ve been organizing, we’ve been involved in things. There’s sort of a changing of the guard in the South Asian community. I’d like to think that there’s a political and artistic renaissance going on in the second generation—where let’s say Heems is the artistic one and I’m the political one. And you guys too, Red Baraat. And now we’re getting some candidates that know what’s up.

Do you think your district is ready for a South Asian council member?

I think people are ready for a South Asian council member. People voted for President Obama in this district; I don’t see why they wouldn’t vote for someone that’s born and raised in this district and that’s speaking to their issues. I love this district. I’m not running as a South Asian. I’m not running as a Muslim. I’m running as a progressive person born and raised in this district that has ideas and wants to serve everyone. Nobody can win this seat on South Asian votes alone. You have to have a coalition. And I’m running on a coalition uniting all the people of color and progressive voters in this district.

What changes would you like to see in your district and in the city? What issues are driving your campaign?

My big champion project is to have a senior center that accommodates all the older immigrants of the district. There’s no shortage of senior centers in the district, but there’s not a five-day-a-week program where somebody speaks Urdu or Punjabi, where someone can get a vegetarian or halal meal, where people understand the culture and the religion of the people there, and serve them. You walk around my district and go to the schoolyards, they’re packed with old South Asian people. Some of these people immigrate here later in life to take care of the grandkids, more or less. They’re the least English proficient, they’re the most isolated.

In a city that spends $250 million through the Department of Aging for senior centers, there’s no plan for this community. The Department of Aging told me in writing that they don’t mandate instruction in another language unless 30 percent of the seniors there speak that other language. But if you don’t have instruction in your language, nobody from those communities is ever gonna go. It’s a Catch-22. If there’s one thing city government does it’s senior centers. This is nothing new. But certain people are being left out of that right now.

I know you were involved in the campaign to support Punjabi Deli—a small restaurant in Manhattan frequented by taxi drivers—and helped them get a temporary taxi relief stand installed by the city after a long fight. Does that overlap with issues you’d want to work on in City Council?

I cannot name a single elected official who is going to bat for taxi drivers. There are a lot of yellow, green, and black cars parked outside of homes in my district, and they need a voice in city government. I’m proud in my law practice to be serving so many taxi drivers. Bhairavi Desai of the NY Taxi Workers Alliance sends me all the taxi drivers who have been wrongly arrested, and I defend them. I go to bat for them in court.

Taxi drivers are important to me, and they’re important to this community. The ground transportation business subsidizes so many South Asian households—we need a champion. It’s also outrageous to me that there is no one on the TLC’s (Taxi and Limousine Commission) nine member commission who is a taxi driver, former driver, or driver advocate. Not one. In my law practice, I’ve had so many cases dismissed against drivers. The problem under the system right now is that TLC will suspend your license upon arrest, not conviction. So you’re off the road up until your case is over. And these cases take two, three, four months to resolve. There’s such prejudice in the system. Basically, if you’re a taxi driver in NYC, you’re guilty until proven innocent. That’s a violation of due process. No one is speaking up for these workers. They’re being totally harassed by the city.

Where in the campaign process are you now? What are the next steps?

We have to get on the ballot. Petitions are due by July 9. You have to get 450 valid signatures from registered Democrats in order to qualify. There are always challenges that people do to try to knock each other off, so you gotta get a lot more. We’re looking to file over 1,000. We’re almost there. I’ve got to raise a ton of money. I’ve raised about $25,000 already. I have a bunch of fundraisers planned—like four fundraisers next week. So it’s really just raising money, getting on the ballot, and you know, knocking on doors and going straight to voters. There’s really no shortcut. I love people, I love hearing everyone’s story. I’m meeting everybody under the sun. I’m meeting wonderful people. I’m meeting some…some colorful characters [laughs]. And I’m getting to hear everyone’s story. And everyone’s story matters.

Anything else you want people to know?

I want them to get involved. This is a historic campaign. If you’re a progressive, this is the campaign to get involved in. This is a region of the city that is not known for progressive politics, but has the potential to elect somebody that can bring a progressive voice. It’s a chance to bring an entire community into the progressive fold.