A conversation about humor, race, and the search for decolonized jokes

February 6, 2015

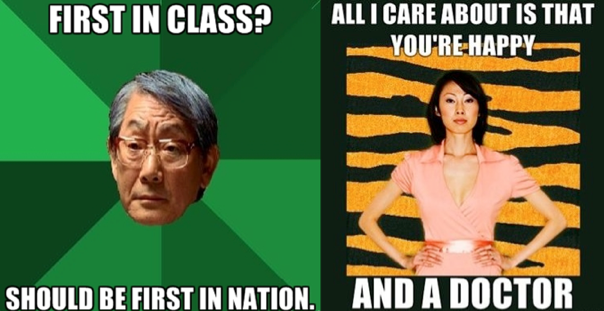

“So, I can’t ever make a joke about black people because I’m white?” Jenny Zhang constantly hears this kind of comment.

Her response: “No, you worthless twat. No one is taking away your right to make shitty jokes that any brain cell could imitate and disseminate. It’s that your jokes about black people—as well as brown people, subalterns, poor people, cis and trans women, and anyone else who is reduced by humor—suck.”

Zhang, author of the poetry collection Dear Jenny, We Are All Find (Octopus Books) and contributor to the teenage girl magazine Rookie, is by no means squeamish when discussing the politics of identity. Her poetry, fiction and essays constantly push beyond comfort zones to confront a deeper sense of where racial and sexual bias comes from.

Over several rounds of email messages, Zhang discussed with Monica McClure, author of two nerve-hitting chapbooks Mood Swing (Snack Press) and Mala (Dear Claudia), how contemporary comedians both toe the line and transgress it in addressing cultural differences in their acts. Most recently, when Tina Fey and Amy Poehler joked about Bill Cosby’s alleged sex crimes at this year’s Golden Globes, they impersonated his voice in a near minstrel fashion to skewer him. “I’m okay with using humor to shame a rapist,” McClure says. “But I remember thinking to myself, ‘Here we go again—putting aside race to make a feminist statement.”

Later in the evening, Margaret Cho spoofed a North Korean general who had become a member of the Hollywood Foreign Press Association, in what seemed to be a blatant example of “yellow face,” McClure observes, undermining the complexities of her performances that expose white perceptions in powerfully subversive ways. But here she just served “the audience a fantasy they already cherish”—that feeds off of offensive North Korean stereotypes.

For Zhang, the issue is far from black and white and mired in its own set of complexities: “As it turns out, you can be a white person and a make a great joke about white privilege and white supremacy,” she says. “Look at Louis CK! He did it.”

— Sharmila Venkatasubban

Louis CK’s stand-up routine on white privilege and time machines.

Jenny Zhang: It feels true to me that I am a woman of color who is, in many ways, highly visible, in large part because of my youth, education, privilege, and conformity to conventional, accepted standards of beauty and femininity. But I’m also totally invisible for those same reasons. Humor becomes a site of control for preserving my humanity as a subaltern and as a woman. I think of Junot Diaz talking about the necessity of seeking a decolonized love for people who come from a deep legacy of being colonized. I can’t even get there yet. I’m still searching for decolonized jokes. When you tell a joke, you and you alone hold the punchline, even in cases where you are the punchline. The recipient of a joke cannot choose anything except his or her reaction to the joke, which is humiliatingly parallel to the way we experience any sort of psychic violence. It seems the only power we have is in how we respond. Do we grin and bear it? Or do we ignore, fight, hurl it back, scream, or cry? Are we cool with it? Or are we pretending?

“I think of Junot Diaz talking about the necessity of seeking a decolonized love for people who come from a deep legacy of being colonized. I can’t even get there yet. I’m still searching for decolonized jokes.”

Monica McClure: You raise the question of what makes something funny rather than simply true or, on the other hand, utterly devastating. The assumptions we begin with—that we live in a white supremacist, imperialist, capitalist patriarchy—are bleak. I think of Bataille’s writing on laughter in the gallows. What is the relationship between humor and horror? The joke performs some delicate work. There are the extrinsic elements that make a joke: timing, delivery, and physical affect. And there is the intrinsic: the joke in collaboration with the cultural context it enters once it’s performed. The conflict between personal perception and what a social majority holds to be funny is part of it as well.

Female comic artists like Casey Jane Ellison and Sarah Silverman start their self-effacing bits from the indisputable reality that they’re locked into a system that has subjugated their bodies and minds. “Can I ask you guys a question?” Ellison deflects. “What is your least favorite part of the patriarchy? Anyone?” We’re mute with laughter. We’re beat, and there’s a pain-pleasure quality in sharing this reality. Victor Varnado’s jokes about being a black albino resonate strongly with me as a biracial person who presents as white. He’s got one about watching a white woman move her purse closer whenever a black man walks by. However, she doesn’t do this when he approaches, because she doesn’t know he’s black. So he leans in and says to her, “I’m still going to rape you.”

I remember laughing for five straight minutes and then feeling bad that I had laughed at what was essentially a rape joke. Of course, I don’t think rape is funny. Perhaps I laughed because I admired the cleverness with which he turned the paranoid, white woman’s fantasy about the fantastical threat of black men into a joke about the real threat of all men.

“Perhaps I laughed because I admired the cleverness with which he turned the paranoid, white woman’s fantasy about the fantastical threat of black men into a joke about the real threat of all men.”

JZ: Humor outs people. Sometimes that means the person making the joke outs him- or herself (and this can be purposeful or unwitting) and sometimes a joke puts the audience in the position of: Do I reveal myself? Do I play along? Do I let this joker think he/she has put me down successfully? This isn’t always fun. You either laugh and you’re cool with it or you don’t laugh and you’re an easily offended humorless bitch.

I’ve heard certain jokes countless times: “You wanna know why I’ve never tried to fuck an Asian girl? [Beat] ‘Cause they got sideways pussies.” Those jokes make me unable to be my own subject. It doesn’t have to be that obvious either. One time, at a very civilized work brunch, my colleague was talking to me about a student from Africa with an unpronounceable name. It was a very minor joke but he expected me to chuckle at how hilariously hard it must have been to go through those eight weeks of class struggling to pronounce this student’s name. I must have balked or something because he immediately retreated from his jokey demeanor and wanted to clear the air about what he was laughing at—that, in fact, he was NOT racist, that he absolutely was not making fun of this guy who speaks a language other than the one we currently were speaking. And to prove it, he added, “I mean the guy literally didn’t have any vowels in his name.” As if it were just a universal truth that if you are born a human being, only names with vowels are pronounceable.

It’s like people thinking badly translated English is hilarious. There are whole websites devoted to how some supermarket has a sign in English that says, “A time sex thing,” next to a picture of a coffee cup. I mean, I don’t know, maybe if it had said, “I farted into my own eye,” I would laugh. It’s not that I’m “above” this type of humor. But if I laughed at every instance of badly translated English by Chinese people then, whoo boy, would I find my parents hilarious. How am I gonna get through dinner if I fall to the floor, dying of laughter, every time my mother says, “I brought home a smoking turkey for you” or “Your writing is so toucheable?” This is not to say that my own internalized racism and self-loathing has freed me from using her English as a point of mockery and insult when I want to put her down or distance myself from her.

“Sometimes a joke puts the audience in the position of: Do I reveal myself? Do I play along? Do I let this joker think he/she has put me down successfully? This isn’t always fun.”

All this makes me feel like a humorless bitch (again) which makes me feel completely turned around because I laugh all the time. I find so much shit funny. It’s like that Le Tigre song, “The Empty,” where Kathleen Hanna sings:

I sat thru yr movie but I didn’t see anything

I went to yr comedy club and didn’t laugh at all

I went to yr movie and I didn’t hear anything

I went to yr concert and there was nothing going on

MM: The idea that your laughter can enable a joke to succeed, filling its moment to the fullest and then dying, is deeply unsettling when you think of how easy it is to laugh out of habit, relief, or pressure to conform. Do you remember ever regretting laughing? When I was in high school, my friend Murray fell into a bonfire. We saw it happen from a distance, and as horrifying as such a thing is, we laughed ourselves hysterical. Even as we drove him back to the house in our four-wheeler, we told him he “smelled like brisket.” We swore he had been laughing with us. But he couldn’t have been. He had very serious burns and was in a lot of pain. Can you go back and criticize or re-contextualize the joke and your response to it with fidelity if you were part of the reason a joke succeeded?

My Mexican-American family celebrated early George Lopez’s stand-up, less out of an identification with a shared cultural experience than out of a mutual desire to see a Chicano comedian speaking with authority in mainstream media. He was making us visible and funny. In an early act on the same stage where Richard Pryor once famously performed, George Lopez compared the way Mexicans discipline their children with the way white people discipline theirs. How different, how odd, how backwards it must sound to white people to hit children in public. And he is a buffoon on stage—very physical in his mimicry of the impulsive, juvenile way we discipline our children. I’ve heard George Lopez called “America’s Mexican,” which implies that he’s giving mainstream America something digestible. Nonetheless, it makes me laugh. Sigh. Maybe there’s a difference between caricature and exaggeration?

“Can you go back and criticize or re-contextualize the joke and your response to it with fidelity if you were part of the reason a joke succeeded?”

JZ: What makes something funny? There has to be something strange, something enticing, or something that surprises us. But it also has to be familiar—in other words, the person laughing has to find it to be true. But here is where the subaltern and the colonized can be left out of mainstream comedy: When your experience of life is so radically different from someone else’s that what they find strange and exceptional, you find banal, or what the subaltern finds true is unbelievable or unseen to another. Wanda Sykes’s comedy bit about “detachable pussies” or various comics lately who have tackled “reverse racism”is incredible to me because these comedic bits start from the assumption that it is undeniably true that, for example, we live in a rape culture, or that this world is girded by white supremacy.

Wanda Sykes imagines the convenience of detachable pussies.

I often see comedians trading in the stock of patriarchy, imperialism, homophobia, and transphobia—and then complaining that their detractors don’t get “edgy” humor. I think there’s a way to be edgy, to talk about cunts, to talk about black and brown bodies without enforcing all that toxic shit. It depresses me because I often wonder how the truly radical as well as the true soothsayers and seers can ever wield popularity or stronghold? There are too many people willing to laugh at a punchline that is simply, “Mexicans smell bad,”or “I hope that woman gets raped.”

MM: I demand that my outrage be considered funny. It’s with glee that I use racist jokes that were used to shame me to make white people uncomfortable. “Be careful. I’m Mexican. I will get pregnant if you so much as cum near me,” I say to lovers. “Don’t worry. I’m Mexican; I was built for hard labor,” I say to my co-worker. But then you have to be ready for that horrible moment when someone actually laughs in agreement.

JZ: It’s the Kurt Cobain moment of realizing that the crowd was full of exactly the kind of misogynists and brutes he railed against in his songs. It’s the Dave Chappelle moment of realizing he was the n-word white people in the audience were laughing at. People minimize it by saying, “Oh, Dave Chappelle became bat-shit crazy and went to Africa.” Well, what if he’s not bat-shit crazy, what if he’s supremely sane and just realized that he was fighting a losing battle? I was once asked to read “sex-themed” work at the Poetry Project. So I read a handful of poems making fun of Asian fetishes and people who ask me questions such as “but where are you from originally,” and tell me perfectly sincerely that I have “intoxicating almond eyes and rice paper like skin.” After the reading, this white dude was literally like, “I loved what you did up there … are you from China or Japan?” and then proceeded to regale me with tales about his many past Asian lovers. I thought, “I give up.”

“But here is where the subaltern can be left out of mainstream comedy: When your experience of life is so radically different from someone else’s that what they find strange and exceptional, you find banal, or what the subaltern finds true is unbelievable or unseen to another.”

MM: I think what’s true about our lives is often employed in the joke as fantasy. “A Mexican and a Black guy are riding in a car together. Who’s driving? [Beat] The cops.” The joke’s work here is surprise. I remember when I was told this joke for the first time. I was young and I felt a little goaded into laughing. It was as if I wasn’t supposed to be able to guess “cops” because I was white. I think I was laughed at for not laughing, and didn’t mind. It had just made me sad because the experience wasn’t painfully mine to reframe. It couldn’t be more clear when I’m being excluded from the joke for being white, or the opposite.

JZ: That makes me think of the time when Sarah Silverman infamously defended her right to use the slur “chink” in her jokes, and the president of the Media Action Network for Asians, Guy Aoki, took her to task for it on “Politically Incorrect” with Bill Maher. She actually demanded an apology from him for accusing her of being racist and not doing satire correctly. And that’s how I remember her—defensive about her right to be racist, which doesn’t even really stir me at this point. But what really bothered me was that she was defensive about her jokes working, insisting that she deserved an apology because some pissed-off Asians said her joke wasn’t funny.

But I also remember her on the brilliant but short-lived Kamau Bell show. Have you seen it? She talks about her Comedy Central Roast and how much it hurt her when a couple of comedians started making fun of how she looked like an old woman. This particular interview is interesting because she’s essentially saying the opposite of her party line, which has always been: “If you are offended, you don’t get it.” For her, some things are sacred and off limits, and of course, those things describe her identity: a thirty-something white woman. So the most hurtful thing to her is making fun of a woman who is no longer considered young. And in a way, she makes a great point when she says that roasting her for being old is like saying, “Your joke is that I’m still alive.”

But she can’t make the connection go any further than herself. Because I would argue that any joke where the punchline is RACISM=HILARITY—for example, Mexicans smell bad; Chinese people look like they’re napping but it’s just that their eyes are so small; black people are criminals—hurts me on exactly the same ground that Sarah Silverman was hurt by the jokes about her age.

Okay, so we laid out what isn’t funny. Well, what is funny?

“I think what’s true about our lives is often employed in the joke as fantasy. “A Mexican and a Black guy are riding in a car together. Who’s driving? [Beat] The cops.” The joke’s work here is surprise.”

MM: These things make me laugh:

The idea of wearing a diva cup in case you ever need to throw menstrual blood in a man’s face like you would a glass of wine. At-home abortions. At-home liposuction. At-home hysterectomies. Pro-anorexia sites that remind you to get naked and look in the mirror and pinch your fat anytime you feel like eating. The idea of loving your girlfriend so much that you would sit in a hot tub full of your period blood together. Sacrificing one man per cat-call. Saying your diet goal is to get down to your birth weight. When a man asks for my Friday night plans and I say, “Throw up and die in the streets.” When I am depressed and I say, I love you but I literally have no feelings right now. Depression is funny. Familiar existential circumstances set up as absurd either/or situations are funny to me. Get your period? Kill yourself. The idea of there being no way out. The idea that life is meaningless, and yet still worth living, can run through a joke about suicide and make me laugh. It has to be thoughtful, though. A flippant, crass or unoriginal suicide joke fails.

Comedian Aamer Rahman on what reverse racism would really look like.

JZ: Depression is funny to me too. But again, only in the right hands. In the wrong hands, it’s shallowly cruel at best and deeply boring at worst. I mean, mental illness and depression and suicide aren’t like flavor packets to add to your enjoyment, but what is the point of comedy if it can’t refer to our own most wretched selves, if it can’t comment on the utter hopelessness of human existence? No one who is inside the hell of mental illness wants their hell to be someone else’s decoration. I wish there was a common sense way of saying: “Have a fucking heart. Pay attention to it. Listen to it.” That’s the only prescriptive advice I can think of when talking about how to responsibly joke about things that can feel too sacred and too raw.