Padmini Naidu, also known as the Blasted Brown Blogger on Tumblr and co-host of the ALTBrown podcast, talks about growing up brown and goth metal head in Hollis.

April 8, 2016

“I’m literally the only brown girl jumping into pits, flying off stage. And then everyone’s like oh, it’s just Pady,” Padmini Naidu, also known as Pady Cakes, tells me.

Pady is a self-proclaimed brown metal punk head. She sings ghazals for fun and can throw down on the guitar. On Tumblr she is known as the Blasted Brown Blogger and the co-host of the ALTBrown podcast.

Pady and I meet the day before Thanksgiving to chat about her work on the podcast and what alternative lifestyle means to her. We brave the line of last-minute pastry buyers at Martha’s Bakery in Queens for approximately five minutes before settling for an empty table at a Starbucks coffee shop down the block.

It is my first time meeting her, but it feels more like a reunion. Pady is boisterous, and always laughing. A woman sitting a table over shushes us loudly, but we continue chatting. Our conversations swing from her experience growing up Guyanese in Hollis during the early 90s, to her graduate studies in psychology, and to her latest Comic Con costume: Bollywood Batman.

The ALTBrown podcast and Blasted Brown Blog aim to highlight alternative voices in communities of color. Each week, Pady and her co-host, Sharky, sit down with an artist or musician for real talk and laughs. My favorite episode of the podcast featured Saraswathi Jones: singer, songwriter and “post-colonial pop punker”.

I ask Pady questions about the work that goes into creating and co-hosting a podcast, but it’s not exactly work for her — just an extension of her lifestyle and the friendships she’s made over the years with other alternative brown folk.

Pady is humble about the different hats she wears and the work she does. I tell her that she does so much outside of her normal job, but she shrugs it off. “I was really excited that you wanted to interview me because I really don’t do anything. But I’m not trying to be humble. I can say that because I haven’t been doing anything different from what I’ve been doing my entire life. I’ve always been an advocate. As a West Indian kid, we talk up and hype up the people we love. Our cousin might be the shittiest rapper, but you support them no matter what. You’ll go see them perform, you’ll buy their shirt, you’ll sing their songs, you’ll start the pit.”

“There’s usually an additional layer of translating to the typical ‘where are you really from’ question people of color are all too often bombarded with on a daily basis. Are you really Indian? Why do you look Indian? Often we are not considered ‘Indian enough’ – whatever that means.”

Pady, who has interviewed metal bands in Trinidad, Jamaica and Barbados, describes everyone she’s managed to touch base with as her online family, her creative family. “We bounce ideas off of each other and we build a bond. If I share my art with you, that’s part of myself. There’s a trust we’re building when we share at with each other,” she says regarding her creative family online.

She started connecting with bloggers, writers, artists, and musicians in online groups right at the boom of social media. But she’s wary of the term ‘alternative’ and the way it is often used.

“When you’re an alternative brown kid, people think everything you do has to be synonymous with alternative. I don’t think I have an alternative lifestyle. There’s a large group of people that are like me. In my experience, I’m alternative because I don’t fit what other people think of as quintessential brown. I’m boisterous, loud, educated. I’m not a pretentious academic — only when I’m writing a thesis. But that’s not every five minutes. And to be honest, I wrote my thesis on comic books,” she adds.

She did almost go down the quintessential brown route in college. She was a pre-med major and studied psychology in graduate school.

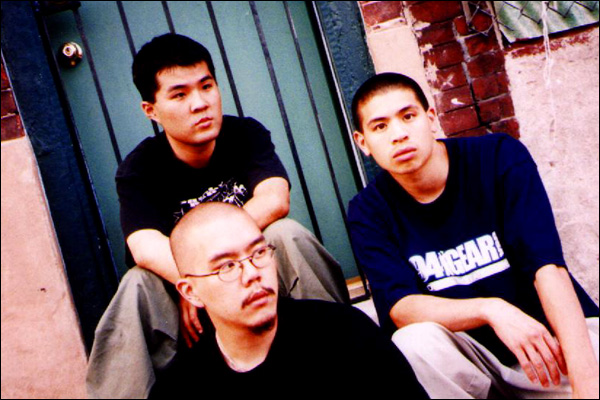

Pady remembers connecting with another Guyanese metal head when she played in a metal band as a high school student. She was surprised that there was someone out there like her. “It’s just weird how you meet people like that on social media. The people that I played with are part of this group called Desi Punks. It’s a Facebook group for brown kids. We were just metal heads and punk kids and I was the only West Indian for miles. Funny enough, in the brown group, I’m still the minority,” she says.

Pady’s words resonate for a number of reasons. For me at least, growing up Indo-Caribbean often meant translating myself in more ways than one for others. There’s usually an additional layer of translating to the typical ‘where are you really from’ question people of color are all too often bombarded with on a daily basis. Are you really Indian? Why do you look Indian? Often we are not considered ‘Indian enough’ – whatever that means.

Yet, our bodies quite literally carry the historical baggage of our indentured ancestors no matter the number of generations removed we are from India. At first glance, many of us are profiled as being strictly South Asians.

Pady locates her roots and sense of heritage in multiple places. She takes pride in her mixed roots. “People are flabbergasted because I have a full Indian name. It’s typical South Indian, but our surnames are usually the bastardization of something longer. I mean, we’re predominantly Indian, but obviously also mixed being from the Caribbean. The best way I can explain myself is through food: rice and beans, chicken curry and dhalpuri, plantain. It’s such a typical meal for us,” she adds.

“When I tell them I’m West Indian, I’m like, not Gujarat. We from the west. Meaning the western hemisphere. Y’all are like Amitabh Bachan and we’re like Nicki Minaj. There’s a big difference,” she jokes.

I grew up on Amitabh Bachan and his angry young man roles, but I also grew up on healthy doses of Buju Banton, Draupaudi and Chris Garcia. Pady’s words speak to the gap between the experiences we both had growing up: passing as South Asian and our Indo-Caribbean culture – a culture often marginalized in the media and during conversation with other brown kids.

The first time Pady was profiled ironically enough was not because of her skin color, but because of what she was wearing. It happened after the Columbine shootings in 1999 when she was a student at Martin Van Buren High School in Queens Village.

“Fitting in at school was a different story for Pady. In addition to being a metal head, she also liked comic books… She jokes that if Snapchat and Instagram existed back then, her hashtags would probably be ‘ethnic goth’ or ‘brown girl goth’.”

“It’s funny because I thought I was in trouble. As a brown kid, now that’s very different. But back then, as a goth metal kid, it’s like it didn’t matter what color you were. You just wore black and people thought you were evil or a Satan worshipper,” she reminisces.

When Pady’s grandfather arrived in school and was told his granddaughter was in trouble because of the trench coat she was wearing, he promptly told off the guidance counselor and then took Pady and the kids to Wendy’s for chicken nuggets before driving everyone home.

“I wanted to learn ghazals so I could metal-fy them. I went to a music class. They couldn’t teach me sitar, so they taught me tabla. The kids teaching me weren’t classically trained, they were learning by ear,” Pady says when I ask her to talk more about her her taste in music. Apparently there are metal bands out there that use sitar. Pady tells me that Type-O Negative, a Brooklyn-based metal band, use both tabla and sitar in their music. In the 80s, electric sitar was popular amongst metal bands.

“A lot of the Indian ragas are played in progressive metal or speed metal because speed metal requires different octaves. It’s similar to how ragas are played. If you’re playing a seven-string guitar instead of a five-string, you kind of cross over into playing Indian-style. You’re giving yourself two extra strings, extra octaves and scales. Same with drums. Add drums and you can go higher or lower, like a tabla player,” she says.

Pady’s passion for metal was never censored by her family members, but her father was curious about it.

“My mom hates it and my dad’s okay with it. I remember the good old days when I would go into the pit and my back wouldn’t hurt. I wouldn’t need ear plugs to go to a concert,” she laughs. Pady comes from an open family. Her grandparents never made her feel different. Pady’s grandmother would help her transform trousers into flared pants with flames. Although her grandfather raised her on Surinamese ghazals, he also supported her love for metal.

“He would take me to Utopia in Hicksville to buy more spike collars and to Coconut’s to get metal CDs. I never stopped loving the ghazals even as a metal head. Metal is similar to what we listen to in our culture. Like tassa [for example] is heavy drumming,” she says.

Pady’s mom was less open about her love for industrial metal and bands like Skinny Puppy, King Diamond, and Ogre. her bedroom walls were adorned with posters ripped out from music magazines.

“And my mom would be like ‘You’re Hindu. What kind of schupidness is this?’”

Her grandfather defended her every time, citing that “she just like a little different ting.”

Still, her father sat her down when she was 14 – Pady thought he was going to give her the sex talk – at the behest of her mom to discuss her metal habit.

“He goes, ‘You know your mom is worried. You’ve been dressing more and more goth. Are you okay?’ and asks me what’s up with my clothes. Mind you, they’re the ones buying my clothes. He wanted to know if I was okay. Although he didn’t understand it, he asked me about it and that is so positive,” she says.

She showed her father a Cannibal Corpse CD with a picture of Kali on it. “And I got ‘Dad, what’s this?’ And he goes ‘Kali.’ And I said that’s the type of music I listen to. It’s just a little fast. It’s like tassa with guitars. I think he just wasn’t sure what it all meant. You know how every West Indian solidifies what they say with ‘Well, yuh hungry?’ Then my dad asked me if I was hungry and that was that,” she says.

Pady compared her love for metal with her father’s love for reggae, Elvis, and Bruce Lee. Cultural dissonance is “He likes very Seventies apartheid kind of reggae: Bob Marley and the Wailers, Peter Tosh. The political and socially conscious stuff,” she tells me.

“And I was like ‘Dad, you know how people look at you weird because you listen to reggae and look like a black dude and people are not sure why you’re with mom because she looks Portuguese and you have two little Indian-looking kids that look adopted?’ That’s how I feel,” she adds.

Fitting in at school was a different story for Pady. In addition to being a metal head, she also liked comic books. She explains to me what she looked like growing up: metal shirts, battle vests, collars, platform Demonias, junko jeans, trip pants, and black bracelets. She jokes that if Snapchat and Instagram existed back then, her hashtags would probably be “ethnic goth” or “brown girl goth”.

That was Pady’s dress-up. “For some girls, red lipstick is their dress-up. Or wearing beautiful clothes. For me that was beauty: being ugly. Being raunchy,” she explains.

Her parents and grandparents migrated from Guyana to the United States in the late 80s. Her parents met over here and then married. “Having talks with your parents if they’re open is still difficult. How do you explain that you’re kind of feeling weird because you feel more comfortable with the white kids than you do with the brown kids? You look like a brown kid, but they don’t accept you. I got a lot of shunning,” Pady remembers.

Pady has visited Guyana three times: as a baby, when she was 16, and four years ago. The last time was the most memorable.

“There’s something beautiful about seeing people that look just like you and talk like you and they love you and they automatically like family. I went there and spoke completely broken. I made it my business to because I’m not gonna talk to my grandma like a basic girl,” she laughs.

‘Broken’ is shorthand for Guyanese-Creole. It’s English, but an alter ego of it — peppered with words from the indigenous, Indian, African, Chinese, Dutch and English languages that washed up on the shores of British Guiana before the empire set. Pady mentions that although there is often a stigma attached to speaking broken, it is an important way of how she identifies.

“It has a lot to do with how comfortable you are as a person and how good you are at building rapport with other people. There are a lot of West Indians who want nothing to do with that. And they think I’m the same way because I listen to metal, because I’m an art kid,” Pady says.