Sudah hampir sepuluh tahun Ambe terbaring di sumbung | Ambe has been lying on top of the casket for almost ten years now

March 12, 2021

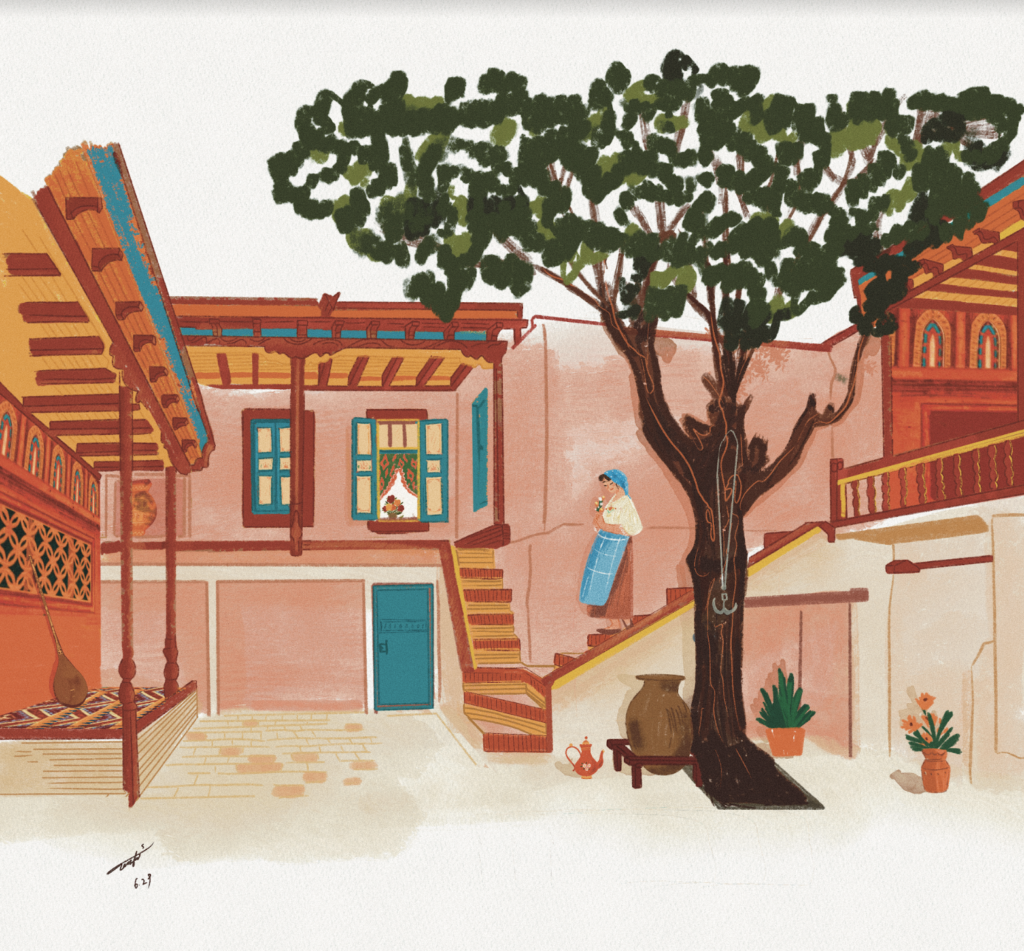

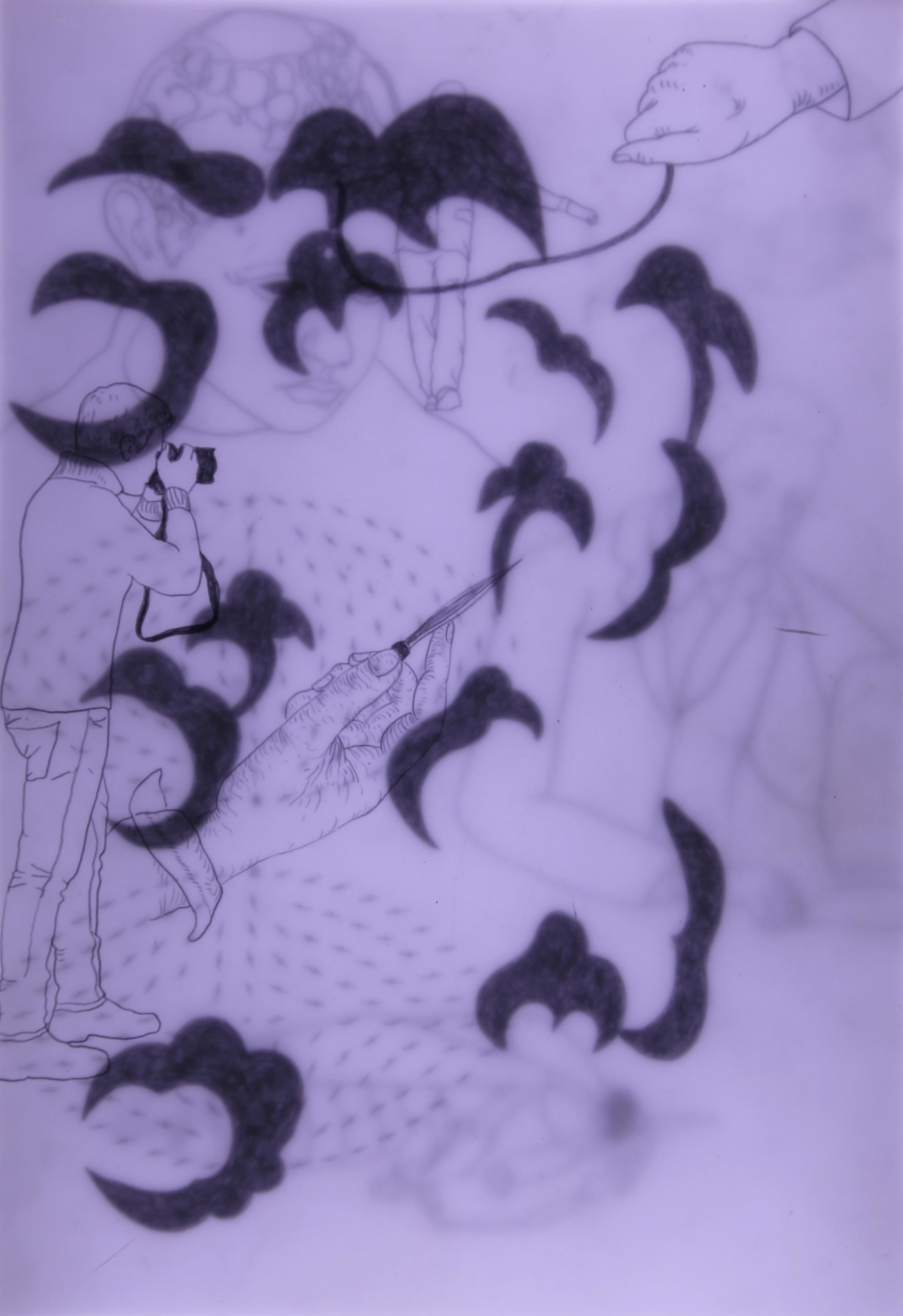

Editor’s Note: Today’s short fiction is part of a notebook of Lullabies published by the Transpacific Literary Project. Each piece of the notebook is paired with a pencil drawing by the artist Trương Công Tùng. Read the other Lullabies in this notebook here.

Click to listen to and read Norman Erikson Pasaribu’s English translation

Ambe Masih Sakit

Di kampungku, Tana Toraja, aura kematian sering kali berembus seperti angin. Jika terlihat secarik kain putih melambai di halaman tongkonan, itu pertanda ada orang yang masih hidup meski sudah mati, “to makula”1. Di sini, kematian dirayakan dengan biaya yang tak sedikit. Inilah akibatnya.

Sudah hampir sepuluh tahun Ambe2 terbaring di sumbung3, seolah menanti upacara rambu solo4 yang tak kunjung dilaksanakan oleh sanak keluarga. Sebab, tak ada dana atau belum dan jauh dari mencukupi walau kami tengah mengupayakannya. Hingga hari ini.

Pagi tak lagi halimun. Kulihat Indo5 sedang sarapan dengan Ambe yang masih sakit, terbujur kaku, rebah di peti pembaringan. Nyawanya menjelma arwah, tapi tetap tinggal kendati tidak menyatu dengan jasad. Menderitakah ia menjadi bombo6?

“Selamat pagi, Ambe. Aku mau berangkat.”

Cahaya matahari, yang bangkit menembus celah dinding Tongkonan, menimpa tubuh Ambe yang susut dan pakaian kebesarannya tampak berdebu.

“Hati-hati, Anakku. Semoga dalle7-mu hari ini berkah. Berkat dari langit.” Jawaban Indo seperti doa.

Sering kulihat rona wajahnya tak ada duka meski ia sudah lama berkabung. Mungkin karena itu hatinya tak lagi berkabut. Menjalani hari dengan bahagia walau keadaan seperti ini. Ia mengantar kepergianku sampai depan pintu. Aku tahu, ia selalu menaruh harap agar aku cepat dapat uang untuk upacara kematian Ambe. Letihkah Indo merawat Ambe?

Cuma Tongkonan8 ini yang kami punya atau yang tersisa. Indo hanya istri kedua Ambe. Katanya, dulu banyak kerabat tidak setuju ketika mereka menikah dan kakak-kakak tiriku menerima dengan syarat menuntut pembagian harta sebagai ahli waris mendiang ibu mereka. Sekarang, Ambe tak memiliki harta peninggalan, bahkan buat perayaan kematiannya sendiri. Anak-anaknya terdahulu pun seperti tak peduli. Tinggallah aku dan Indo yang menanggung beban. Berat, entah sampai kapan kami mampu menahan.

Aku pulang membawa hasil yang lebih dari biasanya walau aku tidak menjadi guide. Lumayan. Ukir-ukiran aku hampir habis dan beberapa lembar tenunan Indo laku. Dibeli oleh turis asing dan lokal yang lalu lalang. Sebenarnya masih siang meski sudah menjelang sore. Dan, aku mendapatkan kejutan kecil.

Margaretha Sua datang berkunjung. Dari Makale ke Rantepao menempuh jarak yang tak jauh. Ia perempuan mamasa dan sudah jadi pegawai. Akhir-akhir ini aku jarang bertemu dengannya. Kami tidak sering bersama setelah ia pindah mengikuti orangtuanya. Kami duduk di kolong Alang9. Alih-alih melepas rindu, wajahnya malah mendung membawa kabar tak baik.

“Upta, dia ingin segera melamarku,” segan perempuan itu berucap. Bibirnya seperti bunga yang kusuka, tapi ia mengeluarkan sengat.

“Kau mau menerimanya?” Aku mengumpulkan perasaanku yang tadi berhamburan untuk mengatakan itu.

“Aku cuma dikasih waktu sedikit buat berpikir,” ujarnya pelan dan tergugu, barangkali isak.

“Etha, bilang saja kalau kita hanya bisa sampai di sini.” Aku terempas seperti udara sisa di hidungnya.

Margaretha Sua menatapku kisruh, “Aku tidak mau jadi biarawati.”

Ia terlalu dirasuki cerita tantenya yang hidup selibat lantaran ditinggalkan kekasihnya yang tak mau menunggu. Upacara kematian bapaknya, kakek Margaretha Sua, tertunda lama. Kini perempuan di hadapanku takut berlomba dengan kematian neneknya.

“Maafkan aku.”

“Aku yang minta maaf.”

Margaretha Sua pergi, pelan-pelan mengabur dari penglihatanku ditelan tikungan jalan. Mungkin ia membawa luka atau lega? Ia seperti tidak setia.

Petang di ambang hari. Senja melumuri langit. Seketika bayangan gelap datang dari barat. Sementara aku tengah memandang di bukit utara itu yang dipenuhi tebing-tebing. Gunung-gunung batu yang di kakinya rimbun belukar rimba. Semak-semak raksasa yang tak habis untuk dikuak.

Mungkin Tuhan menjelma hutan hingga belantara itu dihuni arwah-arwah. Segala yang sudah mati hidup di sana seperti alam baka. Rindukah Ambe untuk ke sana sebagai tomembali puang10? Bergabung dengan tau-tau11 yang asyik bertengger atau bernaung di pohon-pohon suaka ketika malam tiba bagai mengulang masa kanaknya. Seperti apakah kehidupan di puya12?

Dan, sampai kapan aku harus menanggung? Tabunganku tidak akan genap sekeras apa pun aku berusaha. Maafkan aku, Ambe, bila aku mengeluh. Aku sedang patah hati, mungkin putus asa. Indo tidak bisa dibujuk.

“Adalah larangan melakukan rambu tuka13, apalagi rampanan kappa14, apabila rambu solo belum diselenggarakan. Ambemu masih sakit. Rohnya masih terkatung-katung di alam sana.” Kata Indo seolah memegang kukuh wasiat Ambe. Tapi, aku menerka ini kemauannya.

“Kenapa? Apakah itu menyalahi aluk15?” Aku tak tahu apa aku sedang menggugat adat yang aku yakini sendiri.

“Itu sama saja kau meminta hakmu tanpa menunaikan kewajibanmu sebagai anak.” Indo seolah berkata, tunjukkan baktimu.

“Dulu Ambe pernah bilang padaku, hidup itu untuk mati. Dunia ini tempat persinggahan dan mati adalah pintu ke puya, di kehidupan yang sesungguhnya,” jelasku punya maksud

“Iya, itu betul. Lantas?” kejar Indo mencium niatku.

“Kata Ambe carilah bekal, dalle buat mati. Biar kelak tidak menyusahkan keturunanmu. Seharusnya Ambe juga begitu.” Aku tertunduk sebab lancang, ada sesal yang hinggap. Aku tak berani melihat Indo yang mungkin tengah membelalakkan mata, tak menyangka.

“Indo merasa tidak pernah kurang mengajarimu, Upta.” Ia memanggil namaku seakan aku bukan anaknya lagi. Dapat kudengar hela embusnya kecewa, “Ambemu perlu kunci untuk membuka pintu ke puya, rambu solo. Perjalanan ke sana jauh sekali butuh kendaraan, tedong bonga16, agar cepat sampai.”

“Beberapa babi dan seekor kerbau aku kira sudah cukup, Indo. Tedong bonga ratusan juta harganya. Kita mana sanggup.”

“Kau ini! Ambemu keturunan tana bulaan17. Bukan orang sembarangan. Kalau cuma itu, sudah dari dulu Indo melakukan rambu solo. Tak perlu menunggu bertahun-tahun. Dengar, Upta. Ini bukan asal upacara, tapi martabat yang mesti dijunjung. Kau tahu itu! Ambemu akan tersesat karena ulahmu.” Suara Indo melangit seperti bulan yang pongah.

“Aku lebih bangga kau merantau ke Papua. Di sana kau bisa dapat uang banyak ketimbang di sini. Atau kau mau mati di sana, terserah.” Indo bicara terus sebab aku seperti patung, kepala batu. Indo kenal sekali tabiatku, kalau ada mau diam tapi rusuh.

“Kau tidak bakal ada di dunia ini kalau tak ada Ambemu yang meminta kau dilahirkan.” Indo berkata tega. Napasnya panas. Kubayangkan, dulu mungkin ia hendak menggugurkan dan menguburkanku di pohon Tarra18, tapi dicegah oleh Ambe. Keberadaanku kau tampik, benarkah kabar itu?

“Matahari siang dan bulan malam tidak pernah bertemu. Kalau sampai itu terjadi, itu artinya kiamat! Kau boleh menikah, tapi bukan di tongkonan ini dan tanpa restu dariku,” cetusnya mengancam. Indo menarik kakinya pergi ke sumbung, kebiasaannya sesenggukan di sana. Meratapi Ambe dan nasib. Atau masa lalu yang berusaha ia tutup dan simpan?

Malam benar-benar rindang. Beberapa kerabat dan tetangga datang. Kami main kartu sampai suntuk. Aku menyuguhkan kopi dan penganan seadanya. Mereka membawa ballo19. Sunyi dingin meruap.

“Upta Liman, itu bukan sepenuhnya bebanmu dan keputusan ada di tangan kakak-kakakmu yang telah abai di perantauan,” ujar Tato Randa bijak. Ia pamanku dari pihak Indo dan teman Ambe sebagai pemangku adat.

“Seperti bukan orang Toraja saja mereka itu. Mabuk di kampung orang sampai lupa kampung sendiri,” imbuh Urru, teman seprofesiku yang sudah oleng. Entah berapa gelas tuak ia tenggak.

“Kewajibanmu cuma mengingatkan meski kau harus menanggung belasungkawa yang menunda kegembiraan di tongkonan ini,” lanjut Tato Randa. Menimbulkan tanya di benakku yang keruh. Adakah rahasia yang kalian taruh?

“Kecuali kalau Indomu rela memutus hubungan dengan membayar nilai salah yang tak seberapa,” celetuk Tante Ully tak dinyana. Tanteku ini perempuan tua yang agak lain pikirannya. Ia melenggang setelah mendapat isyarat diam dari yang hadir selain aku, pergi menemani Indo di kamar. Matanya bicara padaku.

Kami kembali melanjutkan berembuk, tapi aku tidak berminat lagi. Mereka membujuk.

“Kontaklah saudara-saudaramu itu untuk segera pulang. Urusan ini harus lekas dibereskan. Kami di sini sudah siap memberikan bantuan. Nanti kami ajukan proposal ke pemda buat diikutkan program pariwisata Natal dan Tahun Baru. Babi-babi dan kerbau akan kami sumbangkan. Kurangnya kalian usahakanlah.”

Ah, bantuan ini adalah utang moral. Bakal malu jika tidak bisa mengembalikan, ketika kelak di antara mereka ada yang meninggal. Setara atau lebih dan aib akan aku tanggung bila tak mampu. Masih sakralkah perayaan kematian ini? Mereka pamit.

“Indomu sulit berdamai dengan masa lalunya. Dulu ia berbuat dosa dan mencari selamat. Orang-orang kampung tak jadi mengusirnya. Ketahuilah dari silsilah,” bisik Tante Ully sebelum pulang. Selain kakak-kakak tiriku, yang aku tahu Ambe pernah menikah dengan janda kaya punya satu anak yang tak pernah kulihat dan tidak kutahu keberadaannya.

Ambe, dari manakah aku mulai merunut? Kini aku berbaring lelap di sebelahmu. Hendak menerima jawab.

“Kenapa Ambe menikahi Indo?” tanyaku seakan rohnya masih bersemayam dalam tubuh.

“Karena aku mencintai Indomu.”

Lama kutatap Ambe. Kuperhatikan saksama.

“Apakah Indo mencintai Ambe?”

Sebab ia terlalu lansia buat jadi Ambe.

“Tanyakan itu pada Indomu.”

Ia seolah tersenyum serupa sunggingan orang yang tidak punya gigi. Aku terjaga.

Pagiku dibuka dengan kedatangan tamu. Ribut, suara Indo ramai di halaman ketika aku menuruni tangga. Lelaki itu lagaknya seperti turis lokal dengan badan tambun. Membawa perempuan yang menggendong anak kecil. Tubuh Indo bergetar, kusut dan berantakan, menghalanginya masuk.

“Aku juga punya hak atas rumah tongkonan ini,” tuntutnya tanpa melepas kacamata riben di wajahnya.

“Kamu siapa?” aku maju di muka Indo.

“Aku anak dulu dari Indoku. Istri pertama Ambemu. Aku mau tinggal di Tongkonan ini.” Jelasnya beruntun.

“Rantedoping, kau pergi dan tak ada kabar. Biar nanti adat yang menentukan. Kau pernah terusir dari sini,” Indo bersikeras.

“Itu alasanmu menahanku?”

“Bukan. Karena Upta Liman, anakmu.”

Baru kulihat airmata Indo menetes. Lelaki itu menatapku nanap dan aku terlongo saat Indo hampir rebah pingsan. Kupeluk Indo yang begitu ringkih.

1 Orang mati yang belum diupacarakan masih dianggap sakit

2 Ayah

3 Bagian belakang rumah tempat menyimpan mayat

4 Upacara kematian khas Toraja

5 Ibu

6 Roh yang menunggu diupacarakan

7 Peruntungan, rezeki

8 Rumah adat orang Toraja

9 Tempat menyimpan padi miniatur tongkonan

10 Roh yang sudah diupacarakan berwujud setengah Dewa

11 Boneka kayu, wujudnya menyerupai orang yang diupacarakan

12 Surga

13 Upacara kegembiraan

14 Pesta pernikahan

15 Adat

16 Kerbau belang (albino)

17 Kaum bangsawan tertinggi

18 Pohon sejenis sukun tempat menguburkan bayi-bayi yang belum tumbuh gigi

19 Tuak

“Ambe Masih Sakit” was first published in KOMPAS newspaper March 4, 2012 and later included in the paper’s yearly best-of anthology, Laki-laki Pemanggul Goni: Cerpen Pilihan KOMPAS 2012

Ambe Is Still Sick

The morning is no longer a drape of mist. I see my Indo having breakfast beside my Ambe, who is still sick. He’s lying stiff on top of his casket on the wooden floor. His soul has left his body, and sadly he has to linger here in this world. Does it pain him that he has to be a bombo, a wandering ghost?

“Good morning, Ambe. I’m leaving for work now.”

The sun breaks through the gap between the wooden panelling. It falls on my father. Ambe looks so thin now, his special suit becoming oversized and dusty.

“Take care my son. I hope the one above blesses you today.” It is my mother who replies with what sounds like a prayer.

In Tana Toraja, where I was born and raised, death blows on our face like the wind. If you see a white cloth fluttering in someone’s yard, it means a member of the family is still alive, even though they have died. “To makula”—that’s what we call it. Here, death needs to be celebrated, which isn’t cheap, not at all. And for those who can’t afford it—the living dead is what they become.

Ambe has been lying on top of the casket for almost ten years now. He looks expectant, waiting for the ceremony no one in his family can afford. There’s just never enough money, even though we’ve done everything to save.

These days, I often find Indo’s face sorrowless, even though she has been grieving for so long. Perhaps the fog has also moved on from her heart. And she finally can enjoy the days, in spite of our situation. Indo walks me to the front door. I know she keeps hoping that someday I will manage to scrape together all the money we need for Ambe’s funeral ceremony. I wonder if she is tired of caring for Ambe?

All we have left of Ambe is only this tongkonan house. After all, Indo is only his second wife. People said that many of my mother’s relatives were against their decision to marry, and that my half-siblings would only agree to the wedding if Ambe turned over his late first wife’s inheritance to them. And now Ambe has nothing, not even enough to pay for his own funeral. And those children of his—they don’t care. It’s just me and Indo who are here for him, though I don’t know how long we can live with this.

*

I return home with more money than usual, even though today wasn’t my turn to be a guide. Not a bad day at all. I’ve sold almost all my wooden carvings, and even some of Indo’s handwoven cloth, thanks to the steady stream of foreign and local tourists passing by. It’s still sunny though it’s nearly evening. But I’m greeted with a little slap of surprise

Margaretha Sua appears out of the blue. Of course, Rantepao isn’t that far from Makale, where she now lives. Etha is from a Mamasa family, and she has a government job. We rarely see each other since she and her parents moved. We sit together under the tongkonan house. Instead of being excited to see me, her face is overcast, waiting to pour forth bad news.

“Upta, I think he’s going to propose soon,” she finally manages to say.

I summon all my strength to simply ask, “So what will you tell him?”

“He gave me a few days to think about it,” she murmurs with a mix of frustration and sadness.

“Etha, don’t worry, just say that you can’t be with me anymore.” I feel ejected, like the air that came out of her nose.

She looks a bit irritated. “Upta, I don’t want to be a nun.”

Etha is always so consumed by the tale of an aunt who took the veil after a lover couldn’t wait anymore and moved on. The aunt couldn’t marry him because her family hadn’t yet accumulated enough money for Etha’s grandfather’s funeral. It seems now that Etha might be in the same position soon; she is racing against her sick grandma’s inevitable death.

“I’m sorry.”

“No, it’s not your fault.”

Then she leaves, just like that. Growing gradually smaller, before vanishing at the first bend in the road. I wonder: does she feel remorse or relief? It looks so easy for her.

The sunny day ends; the sky fades to orange. Darkness spreads out from the west as I look hard at the northern hills, with their countless cliffs, and at the mountains with their dense forests, their tangled undergrowth storing countless secrets.

Perhaps God once incarnated as a forest, and that’s why there are so many spirits there. People say everything that dies here now lives there, as if the forest is the afterlife. I wonder if Ambe also longs to go there, as a soul who has received his funeral, a soul that now resembles a half-god? Does he want to play with the tau-tau effigies we’ve nestled in the trees—a get together in the night to relive his childhood memories? What is heaven like?

And how long do I have to bear all this? I know my savings will never cover Ambe’s funeral expenses, no matter how hard I work.

I’m sorry you have to hear my complaints, Ambe, but now I am broken-hearted and losing hope. You know I could never persuade Indo.

*

“It is forbidden to hold a happy ceremony like a wedding or thanksgiving if your Ambe hasn’t had his funeral yet. Your father is still sick, my son. His soul has no resting place.” This is what Indo always says, holding on to Ambe’s last wishes for dear life. Even though I feel she’s the one who wants the funeral, not him.

“But why? Is it so bad to break tradition just once?” I speak, even as I worry that I’m betraying the tribal law I want to uphold.

“It’s like demanding your rights without doing your duty as a son.” It’s as if my mother is saying, show you love us first.

“Ambe once said to me that we live in order to die. This world is just a stopover, and death is a door to puya, heaven, the only life that is real.”

“That’s true. So?” Indo already knows what I truly want to say.

“Ambe told me to work hard so I can fund my own death. So I won’t trouble my children. Don’t you think Ambe should have done the same?” I quickly look at my feet because I have crossed the line. I feel guilty. Perhaps Indo is mad at what I’ve said.

“I don’t remember ever teaching you that kind of thinking, Upta.” Indo uses my name, as if I’m no longer her son. I can hear the disappointment in her voice. “Your Ambe needs the key to open the door to heaven. And he can’t get there on his own; he needs a sacred striped buffalo to take him.”

“Surely, a few pigs and a regular buffalo are enough. A tedong bonga is so expensive. It could be hundreds of millions of rupiah. How can we afford it?”

“How dare you say that! Your Ambe is a noble. It’s forbidden for him to get a normal funeral. If it wasn’t for that, I would have held the funeral long ago and we wouldn’t have waited for so many years. Listen, Upta. This isn’t just another ceremony. Our very honor is at stake. You know that! If you keep saying such things, your father’s soul will be trapped in this world.” Her last words ring out high and shrill.

Indo continues. “I’d be happier if you go to Papua and work. You can earn more money over there. You can even die there, if you want. It’s up to you.” Indo doesn’t stop talking whenever I’m stubborn like a statue. She knows me so well; she knows my silence means I won’t give in.

“You wouldn’t even be alive, if Ambe hadn’t asked me to let you live,” Indo says sinisterly. I can feel the hotness of her breath. I imagine that she once wished to abort me and bury my little body in the Tarra tree, but then Ambe stopped her. I once heard she didn’t want me and I’ve always wondered if it was true.

“The sun never meets the moon, Upta. For if this comes to pass, it will mean the end of the world. You can marry whoever you want, just not in this house and not without my blessing,” she says menacingly. Indo then gets up and heads to sumbung, a bedroom that was exclusive to Ambe, which is now her favorite place to weep for her late husband and her life. But now perhaps she also weeps for a past she wants to hide and erase?

*

The night is windy. Some relatives and neighbors come to visit. We play cards until late. I serve them coffee and simple snacks. They bring ballo, the traditional beer. Other than us, the night is fizzingly silent and cold.

“Upta Liman, this is not solely your responsibility. I don’t understand why your mother hasn’t told you to ask your half-siblings. They can’t just ignore this because they live on other islands.” Uncle Randa’s words are wise. He is my maternal uncle, and also Ambe’s peer in noble rank. “It’s as if they are no longer Torajans, you know. Are they so drunk that they forget their own father?”

Who knows how much alcohol my uncle has had when he says this.

“Your only responsibility now is to remind them; you’ve paid for the food for the mourners who came here. And—why delay bringing a small happiness to this house?…” he continues. My mind is clouded. More questions buzz in my head. Is there something that I don’t know?

“It always amazed me how your Indo had to pay so much for a small mistake they made long ago,” Auntie Ully chirps in, “Why did she have to cut ties with your father’s other children?” She is my odd-one-out aunt. She leaves after the men shush her, walking toward Indo’s room with her eyes still talking to me.

The others and I continue talking, even though I have lost interest. They keep trying to persuade me.

“Please. Just call them and tell them to visit. We have to straighten things up soon. We promise we’ll help. We can submit a proposal to the local government so your father’s funeral ceremony will be included in the upcoming tourist program. Christmas and New Year are just around the corner. We will also help you with the pigs and buffalo for the ceremony. But you have to take care of everything else. You and your step brothers and sisters.”

I don’t know how to answer—I feel this offer will put me in their debt. They will speak ill of me if I don’t repay them when one of them dies. And I’ll have to pay their families at least the equivalent amount of what they offer now. If not, shame will be all I have. Also, listening to what they’ve just said about the tourist program makes me think: are these funeral ceremonies even sacred anymore? They say goodbye and leave.

“Your mother could never make peace with her past. Yes, she made a mistake, and she settled just for social forgiveness. Even though it was nice the people here didn’t cast her out in the end.” Auntie Ully leans in and whispers. “Look closely at your family tree, my dear.”

I’ve heard that, other than my older half-brothers and sisters, Ambe had another child from a rich widow, neither of whom I’ve ever seen or know anything about.

Ambe, where should I start looking? I am sitting on the floor now, Ambe, next to your casket. I am waiting for your answer.

“Why did you marry my Indo?” I ask him, as if he’ll reply.

Because I love your mother.

I look at him closely.

“Did she love you?” I’ve always felt that my Ambe was too old for her.

Ask her.

And then it’s as if he gives me that special smile people with no teeth have and I wake with a start.

*

The morning starts with another visit. As I go down to the front yard, I hear Indo’s raised voice. My mother is talking to a chubby man, perhaps a local tourist. He is with a woman carrying a baby. Indo is trembling; her hair is tangled and messy. She is blocking him from coming into the house.

“I have ownership of this house too, you know,” he insists, without taking off his sunglasses.

I put myself between him and my mother. “Hey, who are you?”

“I’m the firstborn of the man of this house,” he says brusquely. “From his first wife. I want to move in.”

Indo speaks out. “Rantedoping, you’ve disappeared for years! Don’t forget, after your father kicked you out, you never even tried to come back. Let’s let tradition decide.”

“So that’s why you won’t even let me in?”

“No. I do it for the sake of Upta Liman. Your son.”

Indo starts to cry. The man stares at me in shock, and I look at Indo in horror as she falls down to the ground. I go to her and hold her. Her body feels so frail.