Mapping the geography of personal and political histories

May 8, 2018

Ten years ago on a rainy October evening on the 59th street station, I woke up on the R train platform with my mouth hanging open, able to put my tongue through my lower cheeks, and not my lips, through the full laceration caused by a metal shoving a tooth a hundred and eighty degrees and smashing it into my nasal cavity. The night of my accident, I had eaten two muffins but nothing at lunch.

Just after 8 p.m., I left the Asia Society, where I was an associate programmer, on 70th and Park Avenue, after helping usher in guests, when volunteers fell short at a lecture and discussion with director Ang Lee, about his film “Lust: Caution,” I took the 6 train down from 68th to 59th. As always, I stayed two-thirds of the way at the back of the 68th Street downtown platform, and when I had to change for the yellow line to go to Astoria, I ran down the stairs that neatly corresponded with the last carriage of the R train to Astoria.

This maneuvering saved me approximately a minute of my commute back and forth from work, but that evening the N came, then the W, and then another set of both, but no R. I read Miranda July’s “No One Belongs Here More than You,” as I waited. One more N train came. I checked my watch; it was close to 8:30 now. There were more who had gathered. Their proximity made me break out in a sweat.

Not enough air, I thought. I needed air. I was hungry, and I needed water. My sweat surely picked up the same air the rats breathed and exuded, I thought, as my sweat loosened the grip of my glasses on my nose. The dirt of people’s feet streaked the platform, like a muddied Pollock painting.

I shut my book, and started running towards the stairs, eager to make it to the 60th street exit. The night before, I had slept over at my friend’s house, and my bag was bulky with my overnight clothes. I held it in front of me, and I shuddered, as the air left my lungs.

That was the last thing I remember, running up those stairs.

I woke up with my chin flapping. The blood everywhere was mine. I was able to stick my tongue out through my lower mouth, through one of the three full lacerations, and with my tongue, I realized as I felt my bloodied mouth, that everything about my mouth was amiss.

I screamed.

When the stretchers came, a curly-haired brunette woman and a blonde man stayed with me until I was carried away.

I was wearing a bloodied khaki jacket, a white blouse, and dark brown pants, which were sliced open with scissors by emergency room doctors, as though they were sheets of origami paper.

According to witness accounts, I lost consciousness and fell back down the stairs. My neck twisted towards a metallic jutting, at the side of the subway staircase. This piece of metal rammed straight through my lower mouth, missing the back of my right lip lid by centimeters.

As though it had been my fault, she said something to the effect of, “Aren’t you ashamed of being so honest?”

In the hospital, I was given morphine, and told to urinate so that I could take a pregnancy test, before the doctors completed ultrasounds. My neck was fit into a brace.

“You need to have sex to get pregnant,” I said, wincing at the friction between the neck brace and my gaping mouth. “I didn’t even have enough water today. I don’t know how to urinate on the spot.”

The doctors wheeled me outside the ultrasound room, and left me there, after telling me that they would wait till I urinated, to treat me.

A man was brought in mere minutes later. He was screaming. Someone – the nurses thought his wife – had shot him in the foot. When this did not work in killing him, his wife had tried to set him on fire.

The entire emergency unit went to work on him, as I, on the other hand waited to feel the need to urinate for the next hour. I gave someone my health insurance card from my wallet, when asked.

“On a scale of one to ten,” one of the nurses asked. “How much does your mouth hurt?”

“More than ten.”

They gave me more morphine. When I recovered my medical records later, I found out that I had said “I think the morphine is working.” What I do remember is that except for sharp juts of pain, I could not feel my mouth hanging open, though.

I had to wait to be operated on for a full five and a half hours. Later, I found out that in New York state, I can legally sue the hospital if I am not seen in an emergency room within six hours.

The doctors stitched up the lacerations but did not bother to extract my tooth. They only did this when I made a fuss about it hours later. Then, the square-jawed Asian doctor told me, “You are lucky, it would have cost you at least 500 bucks to get this taken care of in the outpatient clinic.”

I sat on a wheelchair with a neck brace listening to him. The back of my blue hospital gown was strung together by ribbons that were not tied shut, and I felt as naked as my back, as I listened to him.

After the tooth was removed, I was told that the hospital would keep it for their medical records. I felt cheated. Until then, the tooth had belonged to me, been inside my body, been an element of my life that I didn’t think I would have had to part with even in death. However, there my tooth was, half of it missing and probably being devoured by subway rats looking to lick blood, forever separate from me on an aluminum tray next to bloodied gauze. It was the property of doctors who I neither knew, nor who I would see again.

The thing about being South Asian – as is also the case with most women – is that silence is drilled into your system early on, and shame is inexorably attached to speech acts.

Twenty-one hours in the emergency room later, I was discharged. A week later, the hospital sent me a bill for 27,000 dollars, with the claim that I had chosen self-pay, which was taxed at 8 percent. The hospital had asked for my health insurance card a second time when I was in their space, and my colleague had faxed them a copy, after they lost my medical insurance card the night before.

I showed my health insurance carriers this faxed confirmation of my medical insurance details. The time stamp placed me as being admitted for treatment. Eventually, the bill was settled without me having to pay a cent for the hospital’s negligence in recording my information. If I was inundated and unable to call my health insurance company to schedule an emergency visit, I found out that it was the hospital’s responsibility to call the insurance within the first 24 hours and inform them that I was in the emergency room.

The accident was how I found out I’m hypoglycemic. Two hundred forty-seven stitches, 11 surgeries, one dental implant, three and a half years of speech therapy and two years worth of physical therapy later, I left New York City, no longer enamored by the city where stilettoed shift dress wearing pearl clasping women and double-breasted, herring-bone wearing reborn hipsters did not infatuate me anymore. When you have a major health trial and you’re me and it’s time to commit to the long haul, flight risk is high.

———

I had had a long love affair with the city, ever since my maternal uncle bought me boxes of Lucky Charms cereal after a visit in the late 1980s, bringing to life the consumerist world I read about in Archie comics in my native Chittagong. At the age of six, as a scrawny child in Bangladesh, I associated the erasers and rainbow flavored toothpastes that arrived in the mail, as manna from heaven, physical proof of the world that my parents’ comic book collection showcased.

I first came to the United States to study in upstate New York for my undergraduate degree. By the time I left the U.S. nearly 10 years later, I had spent almost every vacation of my adult working life after college in an operating theater, my working days quantifying rape and child soldier figures in countries in the horn of Africa and Latin America, and working with a small fundraising team for a human rights organization, to convince the Swedish, Finnish, and Luxembourger governments to give money to redress legacies of violence.

When my mother first found out that I was commemorating my accident on social media and the impact my accident had on my life, she immediately said I shouldn’t. As though it had been my fault, she said something to the effect of, “Aren’t you ashamed of being so honest?”

The thing about being South Asian – as is also the case with most women – is that silence is drilled into your system early on, and shame is inexorably attached to speech acts. Shame, lojja, it’s everywhere you look. Books written about the topic led to writer Taslima Nasrin getting exiled. It has gotten people killed, people hunted down, because maintaining a certain level of shame is a problematic situation.

As I do often, I ignored my mother’s anxiety. After all, my ancestors have spent a long time either feeling as though their voices must be subdued, or in obsessing how to stay embroiled in politics.

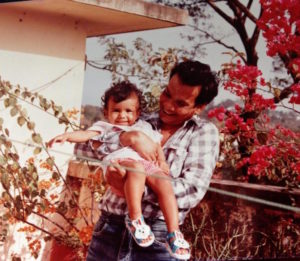

My paternal great-grandfather was the first Muslim barrister of undivided Bengal to study in the United Kingdom, at a time when racism was as alive and kicking, as it is in 2018. After returning home, he worded a memoir and remained active in legislative communities until the time of his death. More notably, he was part of the South Asian bourgeoisie responsible for legislating the first division of Bengal along religious lines in 1905 into East and West Bengal.

The precedent for India’s Partition lay in this first division of Bengal – which then became East Pakistan, and finally Bangladesh in 1971. Pakistan was the first country to dissolve along religious lines, with the formation of Bangladesh, complicating the understanding in the global imagination, that religion can be a unifier amongst disparate groups.

When the British left the subcontinent, both sides of my immediate family were displaced by the Partition in 1947, whose roots lay in my grandfather’s social nationalism work decades earlier. The ethnic cleansing left immediate family scrambling, often during midnight hours, to escape the countries they had been born in. Today, my mother’s immediate family possesses passports from India, Pakistan, Bangladesh, and the United Kingdom.

I have a complicated and profoundly upsetting relationship with knowing that my great-grandfather helped legislate political boundaries along religious lines, especially since he married a Scottish woman who was shunned by conservative members of his own family, and he by hers. A revered barrister and member of the Muslim League in Pakistan, he was responsible for helping expand the British Raj’s divide and rule policy, a colonial power-wielding strategy whereby different ethnic groups were the pawns to showcase how coexistence was futile.

It had been a leftover of the first war of Independence against the British, when Hindu and Muslim soldiers joined forces to protest being forced to bite into bullet cartridges as soldiers – cartridges filled with pig and beef fat, and therefore repulsive to practicing members of both religions.

If you know much South Asian history, you already know this kind of welcome did not last long.

My grandfather’s writings appear to be written to impress his colonizing powers. Each essay meticulously quotes poetry, details artwork, showcases travel artifacts, and sometimes even gives a run down on everything he spent, as he traveled by boat into the Suez Canal, and Egypt and Malta and the Basque region, before reaching London. His love for travel, for movement, stayed with him till he died, and certainly, I’m glad for this worldliness, but the privilege to speak is endowed with exceptionalism and responsibility.

I wonder if he knew what he was involved with, and how his actions would affect his immediate family members’ ideas of nationality, years on. It took me a long time to come to terms with this history, and some days, I feel like as I learn more and grow older, I never will be able to learn enough or understand it. Today, I recognize my great grandfather was a subject of the British Raj, which routinely used religious differences and divide and rule policies among Hindus and Muslims, to address claims among their subjects for autonomy and independence.

———

This past February, I was at a book awards dinner, where a woman I met asked me about my heritage. She was a well-meaning literary critic, who was on the board of the award being administered.

I answered her by saying “I am half Indian and half Bangladeshi.”

“What an unusual combination,” she said.

Given that almost 15 million people were displaced by India’s partition, I don’t think this combination is that uncommon: there must be millions of mixed marriages across India, Pakistan, and Bangladesh, because India as a nation simply did not exist before 1947.

Acknowledging this mixed identity was perhaps novel, for I have seen few do it, and faced severe criticism when I have. But when your past can still lead to a death sentence and communal violence, it’s easy to understand why you would remain silent, or speak in absolute terms about where you’re coming from, or where you’re headed.

My mother’s family migrated from Lucknow to Chittagong in 1947, when India and Pakistan were separated between Hindus and Muslims. Because they were Urdu-speaking Muslims and not Bengali speaking Muslims, the xenophobic West Pakistanis who controlled Bangladesh after Partition, welcomed my mother’s family.

My grandfather received the first exporting license in the country, for his rubber plantation business. If you know much South Asian history, you already know this kind of welcome did not last long.

All Urdu speakers were targeted by Bengalis in 1971, just like the Pakistanis had targeted Bengali speakers in the years between 1947 and 1971. When Bangladesh sought its independence, my maternal grandfather was forced to sign over deeds to his property, and flee the country.

For several days, my mom and her siblings were given shelter by some of their good Bengali family friends. They were advised not to eat near the windows, or to step outside. My mother returned to her family’s house once to retrieve some of my grandmothers’ most valuable china and silverware. At home, she found even the cows kept by some of the workers on the plantation were stripped away, and the family’s German shepherd lay dead. My mother, being an early bookworm, managed to bring back some of her own favorite books, while on the other side of the road, thieves were dismantling the family’s jeep, taking off parts and rolling away the tires.

Both my parents speak broken Bengali in public, Urdu in private to each other, and English to each of my three siblings and me.

The time when Bangladesh’s war of independence broke out was different on who was in control at which city and at what time, and ethnicity played a large part in how this was played out. Sometimes, the Bengali speakers suffered. Sometimes, the Urdu speakers suffered. Sometimes they went against each other. But in the day-to-day encounters I quizzed my mother about in several conversations as I tried to piece together her life, was that if people had not overcome the differences demarcated by language barriers and found common ground in experience, my mother and her siblings would not be alive.

After their host family could no longer host them, my mom and her siblings moved to the Agrabad hotel for several weeks. Newly opened, it was where foreign reporters and officials sent into the country from NGOs were staying. It was safe. Soon after, my mother and her siblings were handed to smugglers, who were assigned to deliver them to India. as their lives were endangered. They left in small groups to avoid suspicion.

My mother was 11- the oldest in her group. Each of the children were instructed to keep a low profile at the airport. Seeing the Bengali authorities approaching, the smugglers— who had guaranteed the three children in the group safe passage— ran away.

My mother and her siblings were taken to a well-maintained Bangladeshi jail, before my grandfather paid off more smugglers to ensure they reached Delhi.

“I didn’t know why I was being targeted,” my mother told a group of my friends and me at Premium Sweets in Jackson Heights this past October. “In my mind, I was Bangladeshi even though we were originally from India, but in 1971, I found out I spoke the wrong language, and Urdu was just not permissible.”

My mother’s family returned to Bangladesh in the late 1970s. Yet, to this day, my parents – both native Urdu speakers with strong ties to India, refuse to address any of their four children in Urdu. It was a language that differentiated them from those in their chosen homeland.

As for my father, when he went to visit family in Bangladesh in the late 1960s from Kolkata, he was stuck there during the 1971 war.

Both my parents speak broken Bengali in public, Urdu in private to each other, and English to each of my three siblings and me. My two sisters and I were shipped off to India and London, as soon as the political situation in Bangladesh began disintegrating in 1996, and curfews and countrywide closures resulted.

My brother, the youngest and only male– stayed back until he reached college age. while the daughters were shipped off. The dangers of my brother being raped were, in my parents mind, much less pronounced than with my sisters and me.

———

After my accident, and when I left New York, I made plans to study for my graduate degree in Budapest. I was excited about the move, excited about the program, until early on in Budapest I was attacked by neo-Nazis in front of a night club in the city.

Left with a torn ligament on my ring finger and a fractured thumb, I internalized this experience, and began to wonder, what exactly is wrong with me? The doctor had a glib solution about what was going on.

“It’s because they thought you were Roma,” he said, as though this was a valid reason to persecute me.

Shopkeepers in Budapest refused to serve me at regular intervals during my graduate year in Hungary. By the end of the year, I was keenly aware, for the first time in my life, about how brown I am. My flight risk tendencies went into overdrive and I spent down my savings, traveling through 24 countries and visiting old friends, sometimes the same countries week after week, as I grew more and more traumatized by the early incident of racism I experienced in the country.

It was only in returning to Bangladesh to work as a communications, advocacy and partnerships specialist with the United Nations Children’s Fund, after 15 years abroad, that I started to come to grips with my 2007 accident.

The country was undergoing an election year, and as is common in a Bangladeshi political crisis, we, the locals, were the ones left hanging as strikes shutdown basic transportation, amenities, food options. Work days stretched into endless curfews for weeks, with cocktail bombs going off at regular intervals on the streets as political parties fought with each other, wreaking havoc on the lives of anyone who lived in certain areas of Dhaka, outside the diplomatic zone in particular.

Meanwhile, for those of us keen to keep a veneer of sanity in the midst of all the political madness, I found myself trying to convince a friend to come to Chittagong to visit with me, by saying, “There were only five bomb blasts today. And they were just cocktail bombs- the stunner effect, you know, you could only lose your hearing- the shrapnel won’t kill you.”

He did not come.

When I moved to the country’s capital for work, I realized being a single secular Muslim female is automatic grounds for getting into unwarranted trouble.

As the cocktail bomb rang in my ear drums and stilled all sounds momentarily, before piercing the night with a pop, that I realized how odd my life had become, as that plane landed.

My landlord called me up one day, and insisted, “Good girls just don’t have the number of male visitors you have in your apartment.”

If I were actually having sex, this would have been a fun statement to dissect, but my visitors were my male cousins and my gay friends Meanwhile, my building manager tried to come into my apartment by saying my landlord had just landed from Canada. The manager followed me around for days, but when he made the phone call telling me my newly arrived landlord wanted to see me, I was terrified. I did not eat that night, in fear of being gang-raped. My landlord and I had spoken just a few hours earlier, and the manager somehow thought that he could say anything, and just the foreignness of Canada, its distance from Bangladesh, was enough grounds for me to open up my front door.

A couple of months later, I experienced a bomb going off in Dhaka, en route to the airport for a training program at the Harvard Kennedy School. My father flew into Dhaka to take me to the airport in a taxi at 2 a.m., just because it is that unsafe for a woman to travel alone in Bangladesh (and most parts of the world) at such hours. As the cocktail bomb rang in my ear drums and stilled all sounds momentarily, before piercing the night with a pop, that I realized how odd my life had become, as that plane landed.

———

The six years after I initially left New York City have been nothing short of extraordinary.

I travelled through 27 new countries while getting a master’s degree, interviewed victims of child marriage and 5-year-old children living with HIV in villages accessible only by boat, and while I have had some unbeatable experiences and encounters, I have also experienced persecution that I never thought possible.

When I decided I needed to see the world and spend down my savings, I was still clueless to base racism, unaware my body and my name are interpreted in ways I have no control over, and will never have control over.

I learned many ridiculous things about traveling and movement in these past five years too: show as much skin at airports as possible, while keeping it classy, especially if you want to get bumped onto business class and not be questioned for having a Muslim name, put on a thick British accent while addressing South Asians if you want to be taken seriously as a female human rights practitioner, and make sure that you go to as many parties as possible, because dancing will keep you sane.

Regardless of these light coping mechanisms, I faced an extraordinary challenge to my sanity, when a good friend, Xulhaz Mannan was murdered in April 2016 by extremists in Bangladesh. He was murdered on the grounds of being gay, and for starting Bangladesh’s only LGBT magazine. In the immediate aftermath, I was unable to grieve, as most of the others involved in the magazine were forced into hiding. Yet, when I wrote about the matter, I found that much of the attention came in the form of an erasure of my other work, and a horrifying suggestion that I was now a spokesperson for the LGBT community, when my work on such grounds was restricted to highlighting HIV awareness and testing in sex worker communities for multilateral organizations, and relaxing with my gay friends.

When I spoke up, I was doing so only because justice was not being delivered, but I soon became identified as an LGBT activist instead of a human rights advocate, the more words I wrote. Activists take to the street, and I don’t. I have written and write about whatever interests me (counterterrorism, food, literature, child rights, refugee crises, weather patterns). It just so happened I had exclusive access to Roopbaam cofounders at the most catastrophic time in the community in recent history. I am a supporter but certainly not a spokesperson for the community. Sexuality exists on a spectrum, and if you can’t cross over from your favored positions to privilege every voice out there, you run the risk of essentializing the narratives.

“We’re all insignificant, until we become insignificant people that both extremists and our own governments want to kill. Be careful.”

A few months after reporting on the gay community, I interviewed hostages who were caught in the 11-hour ISIS standoff in Dhaka in July, which killed 22 people, in Bangladesh’s biggest terror attack to date. The terrorist attack was just two short blocks from the apartment I had lived at, when my landlord thought I was running a brothel in my Dhaka apartment.

During one of the interviews, the hostage I spoke to was seething, not about what had happened to her, but about the nuclear power plant our inept government plans to build in the largest mangrove forest in the world, effectively only five miles from the only natural habitat of the Royal Bengal Tiger.

A budding environmentalist, the 20-year-old hostage told me, “There’s so much work to do. In a way I am glad that I was the only person in my family who was there that night, because I can move on. I don’t know how my parents would have survived seeing people get killed in front of them. I am stronger than anyone I know.”

I wanted to tell the hostage that her parents have probably seen worse than she is crediting them with, but her passion humbled me.

Instead, I said, “We’re all insignificant, until we become insignificant people that both extremists and our own governments want to kill. Be careful.”

For me, this hostage’s passion to fight possible environmental calamities, helped me confront why I never seem to be able to run too far away from extremists: if I stopped talking, even though my voice is minimal, then who else will take that situated knowledge and explain it? As I spoke to this hostage, whose boyfriend had been remanded by the Bangladeshi government for 97 days without just cause, I was amazed by her capacity to think about the passions that fuel her life. As humans we are not monoliths. We have diverse interests, but in a world that likes to highlight anyone speaking of the margins as exemplary of the margins, we have to be careful, in dialogues, about whose voices are privileged, and how they are privileged.

Ten years ago, I was putting together events for the ladies who like to lunch on the Upper East Side, when I fell down the stairs. The night of my accident, the director Ang Lee was talking about his film “Lust: Caution” at my workplace.

I’ve never watched the film, just like I never finished reading Miranda July’s “Nobody Belongs Here More Than You.” Recently, I bought the book again, having thrown away my bloodied copy. I plan to begin reading it on the exact anniversary date of my accident.

The accident spiraled my life out of control in a way that I have rarely been able to admit to myself. And being forced to slow down and seek refuge on American soil has been the biggest source of irritation for me, particularly because my family has been moving freely as far back as I can trace – 400 years, and hails from present day Iraq, Mongolia, the UK, and Burma, alongside the Indian subcontinent.

For me, applying for my asylum was a step in taking ownership over the madness that has been the past few years. Though machete-wielding extremists want me dead as much as neo-Nazis, I am no longer afraid of how I might die, and what I will face on the road there.

Ten years later, I realized my family and I have a knack for being in the wrong place at the wrong time, just by our sheer existence. This in itself is not an exceptional story. Every place I have seen and been to is home, but then again, nowhere I have been to is home, for the home I sustain in my mind, where I was naively unaware of the brutality that is bestowed upon those seen inferior because of their race, blood, sexuality and gender. I find community in those I meet and love to surround myself with people more interesting and smarter than I am, who are thinking outside the box of the systems they have inherited. And nowadays, my past comforts me, for I know the home I seek is one I must continue to shape, through my words and actions.