How art teacher Cecile Chong has connected generations, continents and patterns of migration in her work

June 6, 2019

Flanked by a cluster of her sixth-grade students, Cecile Chong leaned forward gently, brush pen in hand, over a table lined with bright sheets of red paper. Waves of her long, black hair cascaded over her shoulders as she demonstrated, stroke by stroke, how to spell out the character for “pig” using Chinese brush painting techniques.

It was the Saturday before Lunar New Year — the Year of the Pig — and Chong, the art teacher at Sunset Park’s Middle School 821, had invited her students and their families out to The Dedalus Foundation for a children’s event featuring Asian American artists that she had co-organized.

Chong, who taught visual art to every sixth-grader at M.S. 821, Sunset Park Prep, from 2002 onward, makes the city’s vibrant creative scene a familiar facet of her students’ lives. In many ways, as she has cultivated a thriving studio art practice in addition to her teaching career, Chong serves as a conduit between New York’s everyday residents and its arts scene, which, to outsiders, might seem rarified and remote. The Lunar New Year event was a perfect example: For many of the children who came out that afternoon, this was their first time visiting Industry City, the sprawling food, retail and arts complex that signals their neighborhood’s rapid gentrification.

Born in Ecuador to Chinese parents, Chong is accustomed to balancing dual cultures and identities. When I interviewed her in early 2019 before the Lunar New Year event, she was about to shed one of these identities: By the time you read this, Ms. Chong, as she’s known at M.S. 821, will be retired from her career of nearly three decades in the New York City public school system.

An immigrant multiple times over, Chong is the kind of artist whose heritage and body of work, both in the studio and in the classroom, are immediately relatable to many New Yorkers. In celebrating this city’s diverse cultures, she’s won the attention of organizations like the New York City Department of Parks and Recreation, which selected her public art installation “EL DORADO – The New Forty Niners” to tour the five boroughs through its Art in the Parks program through 2021.

Chong connects constantly with other artists, from the 11-year-olds who filled her classrooms to the professional members of the Asian-ish Artist Group that she co-organizes. She is a builder of community who engages with timely themes of migration and cross-cultural exchange in her work, all the while making art accessible to a new generation of aficionados in New York City.

Ms. Chong, the teacher / Cecile Chong, the artist ?

I first encountered Chong’s work in 2017 when I was in the process of moving into the Brooklyn apartment building that we both call home. On the first floor, a huge triptych of her earlier canvases stretches down the hallway, brilliant swirls of reds, yellows, greens and blues. Her work is bold and attention-grabbing, yet sensitive. Anyone who encounters her body of work will notice immediately how often she evokes imagery of children, whether she’s working in milky translucent encaustic (a technique of painting with hot wax) or a rainbow array of abstract fiberglass-and-resin sculptures.

My introduction to “Ms. Chong, the teacher” came the first time I attended an exhibit opening for “Cecile Chong, the artist,” curious as I was to see more of her work and to show her support as a new neighbor. While I’ve covered art in various capacities as a journalist since my college years, I had never seen so many children at an exhibit opening, which typically feature aggressively cool fashions and haircuts, cheese boards and free-flowing wine.

But on a clear, balmy evening in June of 2017, I arrived in Sunset Park, the green space that lends its name to its Brooklyn neighborhood, to find Chong’s students, numbering nearly a dozen, standing alongside her. They were present not as spectators, but as speakers whose voices she wanted heard as they introduced “EL DORADO.”

“‘EL DORADO’ was my first reaction to honoring the immigrant community in New York City by doing it through language,” she told me in our interview at Industry City. The installation pays tribute to the 49 percent of New York City households that speak a language other than English.

Chong, shares the experience of multilingualism with her students. Growing up in Ecuador, Chong’s first language was Spanish. She learned Cantonese and Hakka when she moved to Macau to live with her grandmother, then attended an English-language high school in Ecuador before moving to the United States for college.

At the 2017 opening for “EL DORADO,” Chong’s students spoke about the languages they use at home, Spanish and Mandarin, a mirror of Sunset Park’s demographics.

“Being fluent in Spanish has definitely helped me be successful in being a public school teacher in New York City,” Chong said in our interview. She explained that she began her teaching career in 1990 as a Spanish bilingual teacher in Queens before moving into her full-time arts teaching position in Brooklyn.

Language and the experience of immigration, she added, serve as a point of connection in the classroom: “Knowing that if the kids were born somewhere else, they can connect to me because I’m coming from somewhere else,” she said.

Speaking of her American-born students, she explained, “They were born here, they’re American, but they’re also considered outsiders” as the children of immigrants. “I think we also connect in a way when I tell my stories of being born in Ecuador but also considered an outsider.” When Chong started kindergarten in Ecuador, many of her classmates had never seen a Chinese person before. “China! China!” they taunted — pronounced “chee-na,” a Spanish colloquialism for “Chinese female.”

“I think at the personal level, also, I lived with my grandmother from the age of 10 to 15, and I have some students who also live with their aunts, grandparents. That definitely brings us closer,” Chong said. “We all balance two cultures, it’s either their home culture and the American culture. So that is definitely where we feel a strong connection.”

‘I’m going to bring art to you’

We talked about the day’s event at the Dedalus Foundation, which is dedicated to the legacy of the modernist artist Robert Motherwell and the principles of modern art “conceived in the broadest possible way,” according to the foundation’s website.

While the process of taking students on a field trip to an art museum is daunting — Chong described how that would require collecting permission slips, arranging lunches and supervising 30 tweens on the subway, only to have enough time to see three pieces of art — instead, she said, “OK, if you can’t do that, then I’m just going to bring art to you.”

Chong, who made the Dedalus event open to families and children of all ages, added an extra credit incentive to encourage her sixth-graders to attend.

We headed up the stairs of Industry City to Dedalus, where artists from the Asian-ish Artist Group, which Chong co-organizes with multidisciplinary artists Maia Cruz Palileo and Sara Jimenez and curator Gabriel de Guzman, set up four hands-on stations for the day. Queens-based textile artist Natalia Nakazawa hung a tapestry of a world map, offering thick needles and yarn that the students could use to thread together their families’ points of origin. Chinese paper-cut artist Xin Song made her intricate craft accessible to children by creating a brightly colored paper lantern-making station. In addition to the four hands-on stations, the event included live performances by seven artists and slide presentations of work from 10 artists.

As Chong’s students started to trickle in, I made small talk with them. Every middle-schooler I spoke with told me that this was their first time visiting Industry City. “I walked over,” said one Chinese 11-year-old in a pink puffer coat, clutching a Minnie Mouse backpack purse. When Chong greeted her and her friends, their faces turned like flowers toward the sun.

“The Dedalus Foundation is actually offering space for us to share our work with each other and with the sense of our community,” Chong said, noting that Dedalus’s Sunset Park location also hosts portfolio preparation classes on Saturdays for eighth-grade students from her school who are applying to the city’s specialized arts high schools. “So it’s really like combining, integrating what I do outside of school as an artist, my teaching life, and coming together.”

Arianna Paz Chávez, Dedalus’s education and public programs manager, praised Chong’s ability to create programming that is relevant and useful to young people in the neighborhood.

“Cecile is diligent in serving the local community. She’s great at getting people to cross that 3rd Avenue divide,” Chávez said, referring to the street that separates Industry City from Sunset Park’s residential area. We discussed how Industry City draws Manhattanites to Sunset Park and how the complex, which boasts luxury retail outlets like Design Within Reach and ABC Home & Carpet, might be the only part of the neighborhood that many New Yorkers visit.

Chong, who began working in Sunset Park in 2002, described in our interview how the neighborhood has changed over 17 years. “There were a lot of factories still left in what is now Industry City,” she recalled. “There were very few Caucasian faces — very, very few.” Instead, she described seeing elderly Chinese people getting off the bus at the 36th St. subway station, clutching packed lunches and carrying tea in jars.

At the Dedalus event for kids that day, I spotted very few Caucasian faces in the crowd. Instead, I saw Mexican American kids trying out Chinese brush painting (“Ms. Chong showed us how in school,” one sixth-grader told me) and Chinese American kids learning how to write their names in Korean using custom-made rubber stamps of Hangeul characters made by the artist Heejung Cho.

I chatted up a teenager, Steve Puanta, 17, who was greeting guests at the door. He told me he was a high school senior and an alumnus of Chong’s art class. “She told me not to be mediocre in anything. Once I got to high school, I really understood what she meant,” Puanta, who is Mexican American, said. “We were in a parent-teacher conference, and she said, ‘You don’t have to be mediocre. You can be the best. This is a strength.’ ”

While Puanta doesn’t plan on a career in art, he said Chong’s encouragement and influence stayed with him, which I could see in his choice to volunteer at an arts event on a Saturday afternoon.

Art as politics

For Chong, knowing herself and gauging her energy levels was key to finding the balance between her active studio practice and her five-day-a-week teaching schedule.

“Early on, I did mention to my principal that I have this other career [in studio art] that is very important to me,” she said. “I told her, ‘I don’t have children, but this is my baby that I have to nurture, and there will be times that I have emergencies where I have to run out just like a parent would.”

Chong credited her principal’s level of understanding with her ability to maintain both careers: “She calls it my art baby: ‘When art baby’s calling, you have to go.’ ”

In her artworks, Chong’s passion and engagement with children’s lives shines through in poignant ways. Considering her exploration of themes like migration and crossing cultures, I asked her whether she sees her art as political.

“There’s a lot of stress in this community,” she said, explaining the influence of Trump’s anti-immigrant policies on her students. “I see the challenges that my students share in class. Some become withdrawn,” she added, “I feel that they were told by their parents not to share because they’re afraid, but sometimes they just do it anyway.”

Some of her artwork, she said, is a reaction to witnessing her students’ distress: “It’s hard not to react at this point.” Over the summer of 2018, she said, when news broke of U.S. immigration authorities detaining children in cages, separated from their parents or guardians, she thought of the Chekhov quote, “The role of the artist is to ask questions, not answer them.”

I asked her which questions arose in her work.

“A lot of times it’s ‘How can this be? Where’s humanity in all this? Who are we serving? What are the motives?’ ” Chong replied.

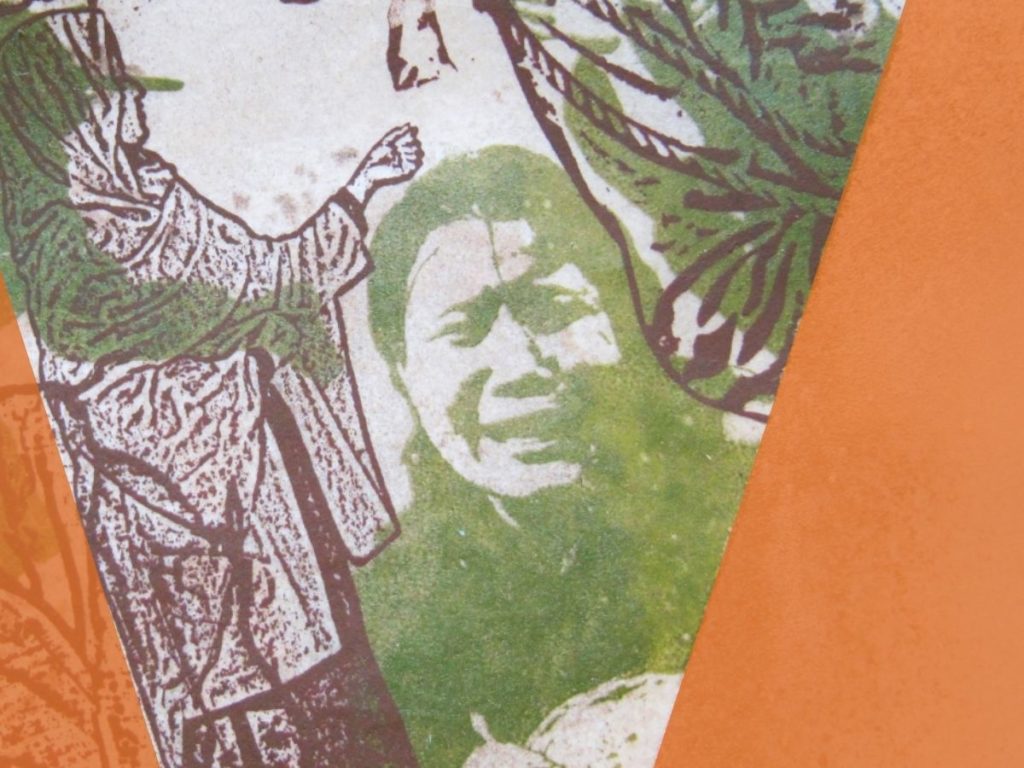

Over six weeks last summer, Chong’s response to the news at the border was a series of layered paintings, using encaustic, volcanic ash from Ecuador, Asian paper and other media. “I called the paintings ‘Bullying,’ ‘Caged In,’ ‘High-Level Negotiation,’ ” she said. On her website, Chong describes these paintings “metaphorically representing layering of cultures, identity and places.” While their backgrounds have a comforting, creamy quality, with delicately marbled backgrounds, her finely drawn Chinese figures, especially the children, appear to mourn, or plead, or retreat into their internal selves.

Photo: From left, “High Level Negotiation” and “Day in Court,” two encaustic artworks by Cecile Chong. Photos courtesy of Cecile Chong

One of the most remarkable aspects of Chong’s approach to teaching is the way that she makes New York City’s contemporary working artists part of real life for her students, something I never experienced in my own K-8 arts education. “I always talk about artists in class, and my students are always asking ‘How come you know so many artists?’ and I say, ‘Well, because I’m a practicing artist myself,’ ” she said.

With the freedom to create her own curriculum, she invited her students to apply the artworks they studied in class — by Alfredo Jaar, Shirin Neshat, Faith Ringgold, Barbara Kruger, María de los Angeles, Ai Weiwei, to name a few of the artists — to their own lives. “Hopefully, I am training them to question, ‘What is the purpose of this artist? What is the intention? What does he or she want to communicate?’ ” she explained. “What are the questions that the artist has, and what are their questions for the artist?”

In the world that Chong built for her students, it was not at all far-fetched to think that they might have the chance to meet living artists who walk the streets of their shared city — or that they might become artists themselves.

‘Everyone is from somewhere else here’

In our conversation, Chong made sure to note how much she, in turn, learned from her students. Early in her education career, when she was teaching English as a second language in Corona, Queens, she noticed how often students would doodle the flag of their immigrant parents’ country of origin. At the time, Chong’s work was mostly abstract, and the strong connection between her students’ art and their roots sparked a new path in her work. “I really began to question, ‘Hey, how about me? How about my identity?’ ” Chong explained. “That really helped me. I feel that in New York, it’s almost a necessity to ground yourself based on either your roots or identity. Everyone is from somewhere else here. Even the ones who were born and raised here have connections to other places.”

For “EL DORADO,” her tribute to New York City’s immigrant communities, Chong hearkened back to her Ecuadorian roots and the tightly swaddled babies, called guaguas in the native Quichua language, that she saw growing up. For the installation, Chong created 100 guagua sculptures by wrapping plastic bottles in layers of encaustic, plaster and fiberglass-reinforced resin, lending them the rippled, folded texture of blankets. She coated 49 of them in luminous gold paint, her statement on the value that immigrants bring to New York City.

“I started with the idea of the swaddled baby, how when we encounter something new, we could also be those babies, blank slates,” she said in our interview. Quickly, she found, the guaguas were also open to other interpretations from the public: Thumbs, phalluses, tombstones, women in burqas — Chong has heard it all. “They look like E.T.,” I overheard a middle-schooler muse aloud during the installation’s Sunset Park opening, a callback to the scene in the 1982 sci-fi film where Elliott wraps his alien friend in a blanket and ferries it to safety in his bike basket.

Personally, I see the guaguas and hear the immortal words of the poet Emma Lazarus, as inscribed at the base of the Statue of Liberty: “Give me your tired, your poor, your huddled masses yearning to breathe free.”

And so it seems fitting that each year following its 2017 opening, this installation is set to nest within another public space, one in each of New York City’s boroughs. From their first home in Sunset Park, Brooklyn, the guaguas traveled to the Lewis Latimer House Museum in Flushing, Queens, in 2018. This summer, “EL DORADO” heads to Wave Hill Public Gardens in the Bronx.

But Sunset Park remains a special place to Chong. It was here, at the “EL DORADO” opening, that I heard a young girl address her teacher before the crowd in such moving terms, a testament to this artist-educator’s impact on the children of her community: “Ms. Chong,” she said, “you are beautiful, inside and out.”

You may also be interested to read these stories:

Mapping Displacement and Resistance in Sunset Park