The poet talks with Eileen Tabios about his writing process and how “language can be a thicket and brambles”

December 8, 2021

Editor’s Note: As the Asian American Writers’ Workshop celebrates its 30th anniversary, we invited current and former editors, writers, community members, and workers to make new meaning from the Workshop’s archive. Together, they have awakened AAWW’s print anthologies and journals, returned to the physical spaces of the Workshop starting from our basement location on St. Mark’s, and given shape to the stories from within AAWW that circulate like rumors, drawing writers back again and again. In revisiting the Workshop’s history, we hope for insight into the ever-changing landscape of Asian diasporic literature and politics and inspiration to guide us forward in our next 30 years. Read more in our AAWW at 30 notebook here.

Among her many contributions to AAWW, the writer Eileen Tabios edited one of the organization’s first print books, Black Lightning: Poetry-in-Progress. Published in 1998, the book is a unique record of Asian American poetics and craft. Each chapter of Black Lightning features a different poet and the drafts of one of their poems, accompanied by an essay by Tabios in which she analyzes the poem’s drafts and includes commentary from the writer. The collection opens a window to the process and thinking of fifteen artists with vastly different styles and concerns: Meena Alexander, Indran Amirthanayagam, Mei-mei Berssenbrugge, Luis Cabalquinto, Marilyn Chin, Sesshu Foster, Jessica Hagedorn, Kimiko Hahn, Garrett Hongo, Li-Young Lee, Tan Lin, Timothy Liu, David Mura, Arthur Sze, and John Yau. Black Lightning also shows Tabios, an emerging poet at the time, encountering the possibilities of poetry and thinking through the impact of artistic choices both small and large within a poem. As she wrote in the book’s afterword, “Black Lightning is many things: a miracle, an exercise in trust, a conversation, an experiment, a matter of idealism, and, ultimately, a love affair.”

More than twenty years later, Tabios—who has since become an accomplished poet and published many collections—revisited Black Lightning and put together a new installment with Arthur Sze. Sze was an integral part of Black Lightning: he is the first featured poet, penned the poem from which the book takes its name, and wrote the collection’s intro. “By illuminating the creative process of [fifteen] poets, Black Lightning widens and deepens our understanding of what it means to be an Asian American writer today,” he wrote in the introduction. “At the same time, Black Lightning makes an important contribution to contemporary American poetry and poetics.”

This new installment of Black Lightning deepens that contribution and shows how Tabios’s close engagement with the drafts of a poem remains a unique path into the mind and craft of a poet. The pair look at Sze’s poem “The White Orchard,” which was first published in the Kenyon Review in 2018 and later appeared in The Glass Constellation: New and Collected Poems (Copper Canyon Press, 2021), Sze’s follow-up to his National Book Award–winning Sight Lines (Copper Canyon Press, 2019). Their conversation reveals how Sze came to invent the form of the poem, which he calls a “Cascade,” and how he embraces uncertainty. As Sze says, “Language can be a thicket and brambles, and I usually have to lose my way in order to find it.” Tabios and Sze retrace that path together and show how a piece can emerge from a “field of energy” and become a spontaneous, sonically elegant, and luminous poem.

Eileen Tabios

Arthur, it’s a delight to celebrate AAWW’s 30th anniversary with you by conducting a new poetry-in-progress conversation as we did for the Asian Pacific American Journal in 1996—an article so momentous it seeded an entire book, Black Lightning: Poetry-in-Progress. It seems apt to note the tenure of this historic organization with a still not replicated project like Black Lightning. For me, the book was special for capturing a moment in time when I was so new to poetry that my questions resulted from an unmediated engagement with your poem we discussed back then, “Archipelago.” I’d only paid attention to poetry perhaps a year before we had our first interview. So I recall that as I was questioning you about “Archipelago,” I was privately also asking questions about this in-the-wild creature—and blessing—called Poetry. In a way, it was “Archipelago” that persuaded me that Poetry was/is a worthwhile companion, then Life, to experience.

I stress the “unmediated”-ness of my experience with “Archipelago” because I came to it without any preconceptions about poetry or the poem. I read it simply based on what the poem presented on the page, not on anything about you and poetry in general. In fact, I stumbled across your poem as the title poem for a manuscript sent by your publisher, Copper Canyon Press, to AAWW; the manuscript was a print-out, not yet in book form. And from that “slush pile,” Archipelago caught my eye. On its own, Archipelago was a powerful collection so that even the younger, untutored me was moved to engage with it. I don’t know that I can ask such “pure” questions today because I’ve since spent two decades with poetry and undoubtedly have formed opinions and hold biases. But I do wish to try again with your newer poem “The White Orchard.” Thank you for giving me and AAWW the chance to repeat the Black Lightning experience.

Arthur Sze

Thank you, Eileen. It is a great pleasure to celebrate the 30th anniversary of the Asian American Writers’ Workshop with an in-progress discussion of my recent poem “The White Orchard.” As I look back, your book Black Lightning was a seminal collection, because it featured the diversity and vitality of Asian American poetry through a personal and wide-open lens.

ET

Before we continue, I’d like to thank the other poets whose generous participation helped bring Black Lightning to fruition: Meena Alexander, Indran Amirthanayagam, Mei-mei Berssenbrugge, Luis Cabalquinto, Marilyn Chin, Sesshu Foster, Jessica Hagedorn, Kimiko Hahn, Garrett Hongo, Li-Young Lee, Timothy Liu, David Mura, John Yau, and (through John’s article) Tan Lin.

Let’s discuss your poem “The White Orchard.”

ET

I appreciated “The White Orchard” when I read it in your book, The Glass Constellation: New and Collected Poems (Copper Canyon Press, 2021). It’s notable that “The White Orchard,” the title poem for the section of new poems, was included in the 2020 Pushcart Prize anthology and also The Best American Poetry 2019. But I appreciate “The White Orchard” even more after seeing just about half of the drafts you wrote. The first logical question would be about the poem’s impetus and/or inspiration. How did you begin?

AS

I began this poem by listening, looking, and playing with language. I didn’t have a particular theme or direction in mind. Instead, I was trying to discover where an image, a musical phrase, a fragment of memory might take me. As I worked through drafts and let phrases emerge out of my consciousness, I started to play with patterns of repetition and created a new form with its own strictures. In this way, the poem that emerged can be seen as an experiment in repetition, musicality, rhythm, and keen attention to silences. If I had to give this invented form a name, I would call it a “Cascade.”

I want to point out how the “Cascade” formally works. Instead of each line starting with the same word, as in anaphora, I decided to see what would happen if each line, including the title as a line, picked up a word or words from the previous line. So line 1 picks up “orchard” from the title. Line 2 picks up “into” from line 1. Line 3 picks up “into” from line 2. Line 4 picks up “on” inside the word “once” in line 3, etc. Sometimes the single word “a” or “the” is picked up. Sometimes “the” is picked up from inside the word “then.” The last line picks up “branches” from the previous line. The title picks up “white” from the last line. The main points of this singular structure are (1) to experiment with varying repetition and deepening musicality; (2) to employ a structure that embodies line and circle: each line picks up an element from the previous line and moves it forward in a particular direction, but it all circles back to the beginning, so thematically there’s the issue of progression and return; and (3) to experiment with whether this formal stricture creates some rigor and reveals some underlying necessity to how the language moves, since the poem is not bound by linear narrative.

ET

I’m delighted we can share the news of your poetic invention! And I feel you’ve named the form quite aptly, given how a reader’s response to a single poem also can be a cascade of a variety of feelings. Now, you shared about 41 of the original 88 drafts before the final or published version of “The White Orchard.” It’s amazing—and wonderful!—to compare Draft 1 with the final version as it shows how “far” your writing process ranged to get to the final draft.

DRAFT 1

While each of Drafts 1 through 17 without doubt can be a stand-alone poem, the drafts also reveal a sense of a gathering of lines with the understanding that they will be subject to future choices as regards inclusion. Is this what was happening with this poem, and perhaps is a general approach given your use of the “list poem” form? I ask in part because these drafts imply an openness to what you may not yet know will unfold, and a welcoming indeed of that uncertainty at the beginning of creating the poem.

AS

Drafts 1 through 17 can be seen as a “gathering of lines,” but I would prefer to see them as phrases that rise out of the emptiness of the blank page, as an “emergence” into language. I don’t consider “The White Orchard” to be a list poem, even though it’s true each monostich has its own integrity and can be viewed as an individual poem. I certainly want to resist knowing too soon where a poem might go or what it will be, and the “openness” you mention is indeed a welcoming of the uncertainty at the beginning of creating the poem.

ET

As I read through your drafts, I came across Draft 7. Here, I sensed that the poem suddenly matured with the second line of the third couplet, “the light-gathering power of your eyes.” Do you have some insight/background/opinion to my reaction?

DRAFT 7

AS

I agree there’s a sudden lift or maturation to the gathering momentum of the poem with “the light-gathering power of your eyes.” Although that phrase isn’t in the final poem, it’s almost an admonition to myself to trust what comes into view. And, in hindsight, it’s interesting that line 3, “the branches of apple trees under a supermoon,” is, in rough form, beginning to take shape as what will eventually become the opening line.

ET

I felt another maturation of the poem with Draft 12. Here, I felt that “connecting of dots” effect with the first and last lines. I felt the poem beginning to reveal muscle for its (completed) self. And the muscle here is epistemological? Any thoughts on my obviously subjective response?

DRAFT 12

AS

That’s such an interesting response. In this draft, I feel the connecting of dots between lines 1 and 2: the opening phrase of the poem emerges here, though I can’t recognize it yet. Yet the rest of this draft moves in a direction that will not ultimately earn a place in the poem. Lines 3 to 9 move into a specific memory of “a friend” who “has disappeared.” The lines here are about Dennis Tedlock, a friend and renowned translator of Mayan texts, including the Popul Vuh. Dennis was trained in Mayan divination (line 4), and conversations with him led me to discover the famous image of Lady Xoc, who pulls a barbed cord through her tongue as part of a Mayan bloodletting ceremony. Although none of these lines make it into the final poem, I believe a thematic tension between absence and presence starts to come forward. With one-line stanzas, this draft asserts the rhythm of language and silence, language and silence. In that way, the poem is “beginning to reveal muscle for its (completed) self.” The muscle is in part epistemological: What is it we know? How do we know it? But there is also a keen recognition of transience (“vanishing point”) that is the emotional force under and behind the language.

ET

The last line of Draft 13 reminds me that I’ve long thought that luminosity is one of your poetic strengths. But it’s not an easy achievement. When it works, the result offers an ease to its surfacing. I feel it as the darkness of text against the page becoming pure light—pure feeling so that the reader no longer grasps a white page with the dark marks of letters but pure light. I felt this effect with Draft 13:

DRAFT 13

AS

Thanks. I believe luminosity has to be earned. If a reader has the sensation of words coming from great depth up into the surface and into light, the poem becomes powerful in this experience. And it’s not an easy task to accomplish. At this stage, I’m surprised to see that the ending of the poem is already emerging. I can feel the upward pull into pure feeling and light, but I also want to say that this is only draft 13 out of 88. It is too simplistic to think that the process of writing is simply pulling apples out of the orchard of a blank page. Language can be a thicket and brambles, and I usually have to lose my way in order to find it. Although the poem at the end may appear spontaneous and polished, I have to earn that language through a path that is often thorny, convoluted, and difficult. Here, in nascent form, is that urge toward luminosity and pure feeling, but the poem has a long ways to go.

ET

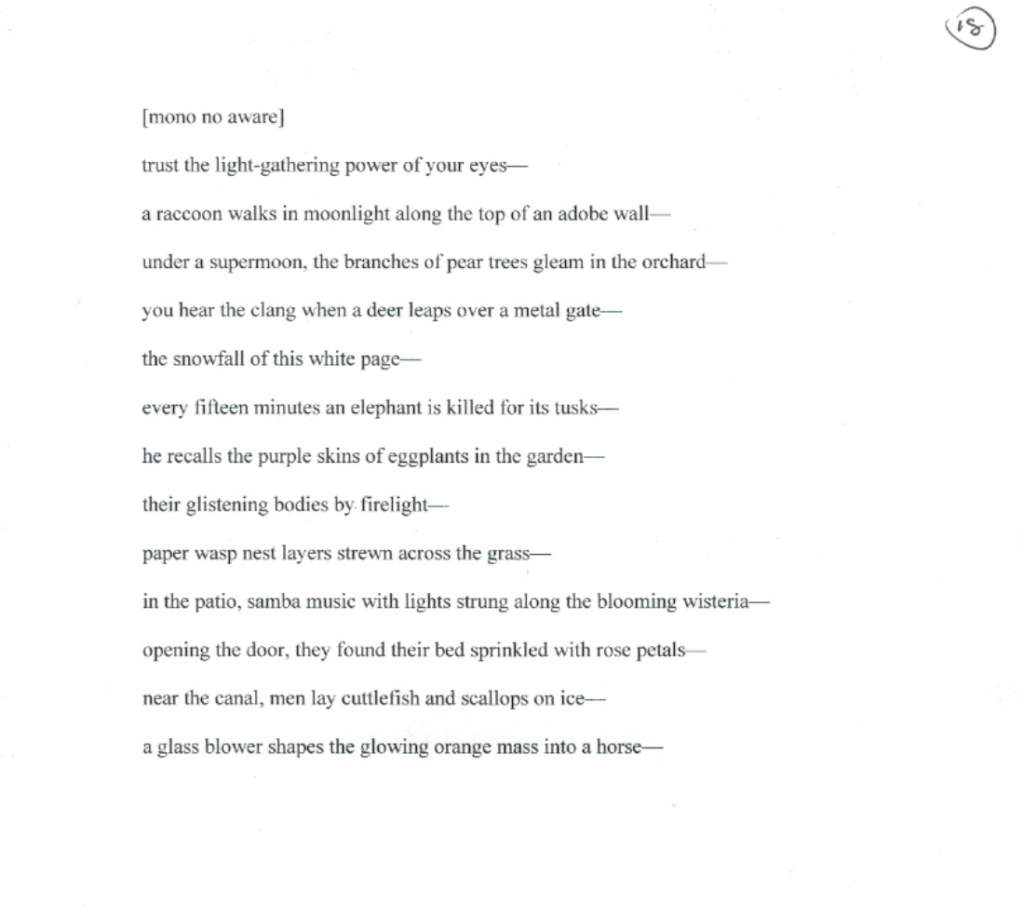

I love how you describe how language “can be a thicket and brambles” and that you “usually have to lose [your] way in order to find it”! With Draft 18, you introduce the concept of “mono no aware.” Was this some turning point in the drafting of the poem? Like some way to unify the variety of your monostichs? Relatedly, was “mono no aware” placed as a first line in the draft as a first thought on what might become the poem’s title, and thus inevitably some sense of what the poem will be “about” (notwithstanding the difficulty of the term “about” in poetry)?

DRAFT 18

AS

“Mono no aware” is an important phrase in Japanese aesthetics. I don’t know Japanese, so I can’t literally translate it, but I associate the phrase with “the poignancy of things,” that there’s a keen attention to things as they are with the simultaneous recognition that they are transient. I put the phrase in brackets at the top of Draft 18 because I was starting to search for the “one” inside the “many.” I was starting to ask myself how do these single lines connect: What is the animating force behind the language? What is the underlying emotion? Where is the rigor? In this draft, you can see many phrases that will earn their place in the final poem, and you can also see lines that will be stripped out. In using brackets, I was clearly thinking that the poem would never have this title but that this aesthetic principle might be a singular thread that could help me distinguish which lines were essential and how to start to connect the one-liners.

ET

This is a classic Black Lightning question—why did you move the line “a raccoon walks in moonlight along the top of an adobe wall—” from the third line in Draft 18 to the ending line in Draft 21? And how is the switch an example of your thought process on how to rearrange the lines?

DRAFT 21

AS

In Draft 18, the first two lines are reminders to myself, and with the third line, “a raccoon walks …”, I am experimenting with opening the poem with that image. In Draft 21, I am experimenting with ending the poem with that same image. At this stage, I am searching for beginnings and endings and am inside a field of energy. In terms of my decisions as to how to arrange or rearrange the lines of the poem, all I can say is that it is intuitive. I will eventually recognize that the image of the raccoon is important to be in the poem, but I will also decide it doesn’t have the imaginative or emotional power to be located at either the beginning or the end.

ET

Why did you delete reference to “mono no aware” with Draft 24? And this deletion also reminds me that you seem to trust the reader a lot. This thought pops up because citing “mono no aware” as a line would be a more didactic line relative to some others. Are you trusting more in resonance and/or the suggestion versus the statement? My rambling question here reminds me that I ask questions that reference narrative content and yet the matter for you as the poet-author may be more of a poetic strategy/technique/form rather than narrative…?

AS

With Draft 24, I deleted “mono no aware” because I no longer needed that kind of reminder to go by. The phrase was helpful up to a point, but now the poem was not bound by that kind of aesthetic vision. There’s a full and rich articulation to the phrases now surfacing onto the page, so “mono no aware” was no longer helpful. At this stage, I’m not following a narrative or linear sequence. Instead, I’m pursuing charged fragments and exploring how to mine them and align them.

ET

Draft 25 reveals itself as seven couplets. The obvious question then is what you considered as you switched from couplets to a “list” form or single-line stanzas. I do notice you switch back to the latter as of Draft 29.

DRAFT 25

AS

In writing a series of monostichs, I don’t consider the lines as a kind of list because each line is free-floating and has its own autonomy. Each line is a microcosm that I trust will eventually connect to a macrocosm that I can’t yet see or understand. In Draft 25, I was exploring whether the lines would have more impact as couplets rather than as monostichs. I was trying to discover if there were connections and urgencies that would be revealed if the poem moved rhythmically in couplet form. By Draft 29, I am feeling that the independence of each line is important, so I shift back to monostichs.

ET

With Draft 29, I see your first use of the em dash; you apply it at the end of each line. So what’s the significance of the em dash? Relatedly, when I compare Draft 29 with the final/published version, you add the em dash even to the last line of the poem. What were you thinking about with that choice? What were you thinking about specifically the use of the em dash at the end of the last line? (It reminds me of when I write prose poems and I delete the period at the end of the last sentence as a visual metaphor for the poem’s ongoing-ness.)

DRAFT 29

AS

With Draft 29, I am envisioning the independence of each line, and the use of the em dash at the end of each line affirms the independence and open-ended quality of that line. With that independence, I am also starting to explore the cadence, rhythm, and syntax of each line. And, yes, the last line of the poem also ends in an em dash because the poem does not have any closure.

ET

Draft 30 raises an indented first line “gazing into the orchard.” Is this the first or second mention of a title? The final title is “The White Orchard.” Please discuss the title’s evolution.

DRAFT 30

AS

Yes, with Draft 30, I am trying out, for the first time, “gazing into the orchard” as a working title. Notice that it embodies the admonition to myself to “trust the light-gathering power of your eyes.” At this stage, I’ve tossed “mono no aware” and am searching for a working title that can help direct the focus and energy of the poem-in-progress.

ET

Elsewhere in Draft 30, we see lines that will end up being deleted, like:

“landscape is autobiography”

and:

“a shrinking cabinet of curiosities whose key is invisible—

It is a singularity unpacked by the human gaze and voice—”

These, to me, are lovely lines; the first can be used easily by others as an epigraph quoted from you. Yet you deleted them, and at this point when I am reading your drafts (since my questions are created from reading the drafts chronologically), I sense a logic to their deletion. That they’re more didactic and weigh heavier than other lines. Your thoughts?

AS

Yes, although the lines are interesting in themselves, they are more didactic. I didn’t feel the last two lines were helpful, in that the “cabinet of curiosities” leads to the whole genre of collecting and assembling visual works of art, and the “singularity” leads into an astrophysics of time and space. In a way these issues are implicitly touched on in the poem, but a direct articulation would be heavy-handed. And the first phrase is, as you point out, more potent as an epigraph or as subtext rather than as an overt assertion. Nevertheless, these are phrases worth keeping and might become seeds to another poem. That is one reason why keeping drafts is important: phrases that don’t find their way into one poem can be the genesis of another.

ET

I am struck by how you keep drafts. I certainly would keep deleted lines because the lines themselves are lovely. But I’m now thinking that it’s this process that might help create a “voice” associated with Arthur Sze’s voice which I, as a reader, happen to find recognizable. I also suspect that if this effect as regards “voice” exists, it may not have been something that was of (conscious) concern but something that surfaced after years of your poetic practice. What do you think?

I also belatedly realize that perhaps another reason your poems are so effective is precisely because you consider each line not to be (just) a poetic line but a monostich. As a single-line poem, or poem itself, this facilitates the clearing away of less-than-effective words or phrases within the monostich because the form is so compressed. After years of reading your poems, I’m almost embarrassed not to understand the monostich’s significance. Any thoughts on this?

AS

Rather than set aside deleted lines, I like to keep drafts because I don’t always know right away which ones might become seeds to new poems. Also, when I go back, if I have the context of a draft, I can catch, as you suggest, a glimmer of voice that helps me recall the emotional nuance of what’s at stake. The key phrase or line might be like the tip of an iceberg, and the draft helps me understand the subtext.

In terms of monostichs, I like the compression and intensity that the one-liners afford, and there are different effects that their usage can enact. Sometimes a series of monostichs in a sequence can suspend linear narration and raise issues of simultaneity and synchronicity (acausal meaningful connection); sometimes the monostichs increase the duration of silences and therefore have an essential rhythmic role to play; and sometimes the monostichs, as poems inside of poems, create miniature resonances that aggregrate and intensify as the poem unfolds.

ET

With “Drafts 65-87,” you’ve compiled your edits from those 23 drafts on one page. It’s the only draft presenting your handwritten marks against typescript. I believe many readers will enjoy seeing the poet’s marks:

DRAFTS 65-87:

ET

Before reading your drafts and our conversation, I read the final version of the poem. So my last questions are based on reading this final version first, and before knowing of your poetic invention of the Cascade.

(1) The transition between the first line—“you gaze into the orchard—” is followed by a visually impactful line with the repeated shapes of circles: moon, the o of orchard, “blower.” Were you thinking of visuality? Because the line is so visual it picks up on the letter o in a number of words and yet you might have been more concerned with sound?

(2) I adore the line “clang: a deer leaps over the gate—” because of how it introduces sound, and specifically, a type of sound that wakes up the listener. By inserting “clang” and not just having the line be “a deer leaps over the gate—” I feel you lift the reader (or this reader) off of the page and away from mere memory; here, utilizing the sense of hearing introduces a physicality to experiencing the line that’s fresh enough to enhance the physicality of the leaping deer by widening the reader’s eyes. Can you discuss the significance of using words like “clang” (and perhaps similar such words) as a poetic strategy?

(3) The line “though skunks once ravaged corn, our bright moments cannot be ravaged—” ends with “our bright moments cannot be ravaged.” The thought made me pause. Do you believe that—or how do you believe that—“bright moments cannot be ravaged”?

(4) I find the combination of these two lines in succession

opening the door, we find red and yellow rose petals scattered on our bed—

then light years—

to be wondrously romantic, for implications as to how the “we” makes time stand still to the sexiness of prolonged fidelity. I wonder what your thoughts were for this particular combination of lines.

(5) Lastly, I think the ending line is brilliant. “Killer line,” as they say. It induces a reflective meta… but really I shouldn’t be putting words in your authorial mouth. (I’m just so enthusiastic!) Please share what you wish about your thoughts as regards (re)turning the poem from worldly experiences to reading.

AS

These are all wonderful observations, and I say “Yes” to all of them. In the first and second lines, I am aware of the visual use of o’s running through those lines, and I am also using the vowel sound of those o’s to anchor or initiate the opening pulse of the poem. With line 7, I very consciously worked with “clang” to disrupt the flow, awaken, and lift the reader off of the page. And, yes, to the assertion that “bright moments cannot be ravaged.” Of course what happens in life can tarnish and ravage us, but the speaker is asserting what Gerard Manley Hopkins asserted, “There lives the dearest freshness deep down things.” I’m glad the line gave you pause, because it’s an important moment to consider. And, yes, to the “roses” and “light years.” I worked over many drafts to find that very short line ”then light years” that affirms the “sexiness of prolonged fidelity.” And, finally, you can see how in Draft 13, the nascent “snowfall of this white page” becomes more physical and also how it opens up the meta dimension with the final line, “branches bending under the snow of this white page.”

ET

Thank you, Arthur. I’d like to ask you now to compare our discussion today versus what you and I shared through our first Black Lightning conversation about 24 years ago for your poem “Archipelago.”

AS

Years ago when we discussed my poem “Archipelago,” I was excited at writing that sequence, and a lot of our discussion went into showing how the different sections coalesced, through juxtaposition, into the ordering of the nine sections. Today, in discussing a single poem, I believe we’re delving deeper into the process of writing poetry itself. And I want to thank you for reading my work with such care and insight.