Writer Ayesha Siddiqi talks to Ashok Kondabolu about growing anti-Muslim anxieties, her new job at Viceland and what keeps people up at night.

September 16, 2016

I first met Pakistani-American wunderkind Ayesha Siddiqi, former editor-in-chief of the New Inquiry and Director of Development at newish TV channel Viceland, at the last-ever Das Racist show in Lexington, Kentucky in 2012. My bandmate Victor Vazquez introduced her as “it’s Pushing Hoops from Twitter” (the Twitter handle she was posting with at the time) and we attempted conversation in a loud backstage area by an exit door for about half an hour before I had to run.

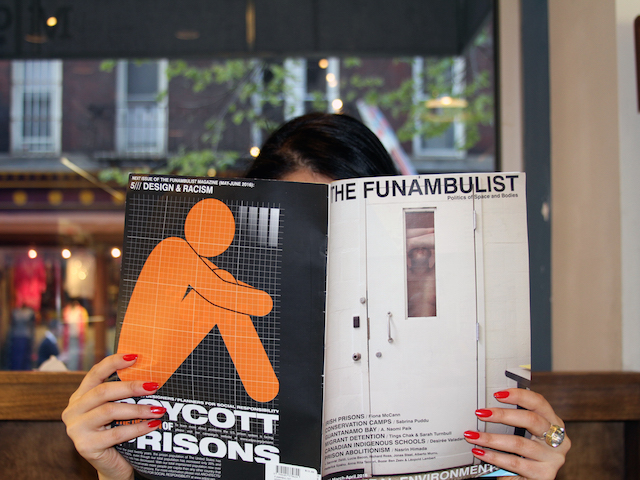

We met for this interview almost four years later at the packed McNally Jackson bookstore in SoHo, where we took a few flicks by the magazine aisle before skirting off to the Grey Dog Café a few blocks to talk about the importance of pronouncing your name correctly, leaving New York, personal style, ice cream, and being Muslim in 2016 America.

Ashok Kondabolu: We first met in Lexington, Kentucky at a Das Racist show in late 2012. What were you doing in Lexington?

Ayesha Siddiqi: I lived there.

Were you going to school there?

My school experience was strange—so was living in Lexington. The interaction between the idea of the South and the lived experience—that friction made it such an interesting place to live in. I think it’s something Southerners struggle with, too. Technically, Kentucky was a border state, but Lexington really embraces the notion of a genteel Southern past. The way we talk about Orientalist understandings of the Middle East and Asia, there’s also a comparable phenomenon that exists in America about the American South. It holds a dual insider-outsider status… One that politicians exploit. It’s true of many places that have competing historical narratives, or rather unacknowledged ones.

You have a dressing style I would describe, if forced to at gunpoint, as cheeky-goth. Did you have an evolution to this point?

I’m as deliberate about clothing as I am with anything else I use or choose to have around me. Self-presentation is always part context and part intent, that equation changes as you’re able to exercise more control over the intent. I pretty much always dressed a version of the way I dress now. Most of my grandmother’s memories of me as a baby involve my insistence on matching my headbands to my skirts. I’m not as bratty now, but still just as stubborn. My dad influenced a lot of how I value fabrics and proportion and cut. His parents also cared a great deal about proper attire, my aunts are very glamorous and I love that it’s something they don’t attach any age to. People resent glamorous kids but honestly, glamor is the only honey in the trap of consumer society. We might as well enjoy it.

I grew up with a preference for classic looks. I wear a lot of black because, with a certain sensibility that I know I’m not alone in having, colorful clothing can feel a bit ridiculous. I wear colors in Pakistani clothing, this is just my uniform for American life. The human experience is goth. The prep part is purely an accident of fate, via the department stores I grew up around. It wasn’t until I went to a very preppy private high school I realized how much people attached to such looks, none of it was as discreet or trivial as I’d thought. The cheeky part must be my sense of humor towards all that: ignoring people’s perceptions of what I may be like in favor of enjoying what I like. My favorite garment I bought recently is a skirt that looks like it was made with the remains of a businessman stitched together—parts of his white shirt and pinstripe suit jacket. It manages to evoke a lot of violence for a wrap skirt.

I’ve only recently felt comfortable wearing skirts and dresses again, I’m fine with being femme, I enjoy it now. But there was a time I began to resent it, it felt like something to overcome. That must be common to girls when as they realize how they’re seen. There was a period in my life where looking younger than I was took on a different meaning for me, I became aware of the assumptions others were led to because of how young I could pass for. I discovered it was an image that held a lot of appeal for people I didn’t want attention from. Older men that liked the idea of sexualizing paternalism. Pink or ruffles were suddenly out of the question. I’d look for simple “gender neutral” clothing or just boys sweaters over jeans and heavy shoes.. It’s easy to equate femininity with vulnerability. Viewing me as vulnerable was a mistake I didn’t want to encourage anyone to make. Now I understand, it’s their mistake, not mine.

It’s not useful for me to worry about these things. For women the constant awareness of our physical vulnerability, the looming threat of violation, produces a unique relationship to our bodies and dress. More encouragingly, glamour is an act rich with the communication of, and control over, our desires and knowledge of our desirability. Control demonstrates more strength than co-opting masculinity. I know that now. I can’t imagine truly changing myself because of other people, I don’t think of them often enough. So I continue dressing the way I’ve always liked to, but with a lot more options for collared shirts and black sweaters. Minus a teenage/early twenties aversion to feminine clothing, my style has remained pretty consistent throughout my life. And of course, being from my family, I always wear jewelry and perfume. I’m aware of how vain I am and how much I indulge my vanity. It’s a private experience, I’m fully entitled to indulging it. Most of my preferences would make me a snob if I thought they mattered enough to impose on others.

What is your relationship with your given name? You also don’t have a name other Americans would recognize immediately.

I like my name, it’s another prized belonging. My dad, who writes poetry, chose my middle name. It’s archaic Farsi for nightingale. Which is fitting because I’ve always been more active at night. My grandmother preferred a more classic name, Ayesha. And my mother liked both. My first and last names are among the most popular names in the world, my middle name is among the rarest. It took me a long time to finally correct white people’s pronunciation of my name. It wasn’t until middle school. People would always throw the extra syllable in the middle of “Ayesha” and it sounded bad and wrong. It initially feels like a rude thing to do—like you’re being self-important by interrupting someone to adjust such a minor detail—but that can become an acceptance of people saying the wrong things about you, or accepting you aren’t worthy of courtesy.

There can be this self-righteousness about it. Growing up in Queens, my thought was how the East Asian kids would adopt the American names but during high school would suddenly change their American names and correct you with their real names.

Nowadays there are digital communities forming around the issues faced by kids in diaspora. I see younger people being more forthcoming about correcting the mispronunciations of their names, I’m glad they’ve found the cues that allow self confidence in themselves and others. There’s a Warsan Shire poem about giving your daughter a name that commands the full use of the tongue. This idea has really resonated with people who turn towards the internet to cope with the white supremacist aggression of their small towns. You don’t have to feel you’re a burden to others by demanding something as simple as pronouncing your name correctly. How many times have you heard “It’s Kirsten not Kristen”… We never think twice about them asking that of us, so it’s not too much for them to do the same.

It’s like when I have a little cousin over and someone says their name wrong I wouldn’t have any problem correcting them for my cousin. Maybe it has something to do with me not caring about my own given name.

I think the impulse behind not correcting someone is wanting to avoid seeming demanding of attention. But really, the message turns into, I’m not worth the courtesy.

What would you do if you weren’t a writer?

Given the opportunities I’ve had in my life, one would think I could just about do anything else. But if I’m being honest, I don’t have the temperament— my personality and the way I think about things—to withstand most situations. I really am partial to the autonomy of the writer’s life. It’s a huge privilege. You’re asking me who I’d be if I wasn’t me. But if I had to choose a new hobby to turn into a living… I love fishing.

And I think it goes with the topics you write about. My question more is what frivolousness would you engage in if you were not allowed to be a writer? But it would have to be a career. I know you like ice cream and shit.

I do like ice cream. If I wasn’t allowed to write then I would still want to live in proximity to all the things people do to cope with how difficult life is, because I think that’s really what art is. That’s what moves people to pursue creative endeavors and I owe a lot to others’ efforts to make the world more survivable.

Did you have mentors when you were younger, either for writing or just in general?

No, I’ve never had a mentor. With the exception of my family, I’ve always had to be what I needed. Lately I find myself asked to be other people’s mentors. Young, ambitious people ask me for advice on careers, media, writing, and publishing, to “get to where I am”, wherever they may think that is. I find these questions alienating because there was never a path I felt available enough to me to follow. Life is more circumstance than choice. And I love my life. But for a stranger to insist your life is enviable or even appropriate for them is bizarre.

I recently had an assistant who eventually became my friend because I was mostly looking for someone like myself in my early twenties minus the self-destructiveness. I don’t plan on having kids so I’m always looking to mentor somebody. But I’m aware of who I am and my limited weird skill set. So it’d have to be someone who was a lot like I am or who I was because I can help somebody who’s interested in those things. Like “Oh you think you want to do ‘x’? Let me bring you to a place where people do that professionally or successfully and you can see: (a) If you think you still want to do this or (b) Those types of people are actually horrible and you don’t want to do this.”

Yeah, that’s the right way to go about it. I guess earlier what I said was a bit discouraging to the concept of mentorship. Working with people who know a lot about life or at least about different types of industry, we have a lot of knowledge between us. That’s worth circulating, especially when it’s information that’s typically less accessible to anyone beyond the already well-connected. I appreciate being able to do for others what no one did for me.

You also said how you’ve never felt you belonged to a place, and that you’re always a traveling person.

I find myself able to live just about anywhere as long as I don’t have to stay. Becoming an American citizen last year concluded a lot of my feelings about myself and this country, and created new ones. Citizenship is one of the greatest luxuries of the world right now for obvious reasons—the mobility a U.S. passport affords, the violence it shields you from.

I’m young and able to be mobile in every sense of the word. I want to take full advantage of that. America is overwhelming, being an American is work. I think that’s the tenor of life in this country for a lot of people. Outside of this country I just felt more instant clarity, a return to what I care about rather than what I’m busy with. Ideally you want as much overlap between the two as possible, but of course that’s not always possible.

An example I always use is the Beastie Boys album Paul’s Boutique, which is such a quintessential album. They wrote the entire album from Los Angeles thinking about New York. That always resonated with me.

Totally. Now that I live in Los Angeles I feel I’ve been given a break from America. This city is the cliff-face of a frontier this country reached a long time ago. But it’s not an edge you’re supposed to jump from. LA is built on adaptations. Almost all of the palm trees here even weren’t originally native to the land. All the nature that’s never fully out of your line of vision helps, the mountains and ocean. No one told me about the sky here, it’s massive. The hills and palms anchor what would otherwise feel like another ocean overhead. The moon rises and falls with dramatic speed, you can watch it happen from the beach until you’re not sure it’s even the moon still. And the weather only ever oscillates between idyllic and natural disaster. The extremes here resonate with me—all the natural and unabashedly constructed beauty carry a fatalism that makes for a soothing landscape because nothing is hidden, the truth of life is built in to what LA looks like. New York isn’t a dishonest city, just a withholding one. There are a lot more alleys and rows of closed windows, that suited me greatly for a while. Perhaps LA suits me now. There’s more to look at here, and from further away, which is a generative distraction.

Especially given the election coverage now, this is a moment of unprecedented anxiety for Muslims in America. It feels particularly unbearable given that Muslims have become persecuted minorities in every corner of the world—with the rising Hindu nationalism of Modi India and the Muslims lynched there, the mass murder of Muslims in Burma, the discrimination and surveillance of Muslim Uighurs in China, who have been arrested for simply fasting during Ramadan. And of course the rising hate crimes in America, France, England, and across Europe. As a Muslim, that’s a lot to be constantly mindful of or aware of on some level. Add to that the feeling that no one else cares, that there are many people that want us dead and even more that aren’t really bothered by it. That’s a toxic perception to hold, I wouldn’t encourage anyone to believe that’s true, but I can understand why they might feel that way given the lack of reaction to this violence. How the media racializes and essentializes Islam created stereotypes Bangladeshi immigrants and women who wear hijab are often viewed through, making them the frequent targets of anti muslim attacks.

There are a lot of flaws within the American pundit class that this election has freshly exposed. One is the way they pretend Trump’s appeal is undecipherable, enough for them to distance themselves and maintain this coastal bubble, to be condescending about all of the America in between LA and NY. As if Trump isn’t just a populist candidate and the most logical response to ten years of anti-Muslim terror media and anti-government conservatism, to strains of thought the media is complicit in, and actively ennobled.

The other flaw in the pundit class is their lack of imagination: their imagined worst-case scenarios if Trump were to come to office—many of those events have already happened or are happening right now. We have had mass raids on immigrants, deporting over 2.5 million people under Obama, many of these refugees from Honduras. Homeland security in many instances targeted women and children. There are families getting torn apart or being forced to spend their days in detention centers. Border violence here or in Europe that migrants from Syria and elsewhere are facing, already exists. People say, “If Trump gets elected then Muslims will be demanded papers and identification based on our religious or racial affiliation.” But being monitored with respect to religious or racial affiliation already occurs. The NSA and Homeland Security have taken extreme measures to monitor Muslims. The paranoia surveillance produces is a factual reality for Muslims in this country. More and more Muslim children are depressed and bullied at school, sometimes more so by their teachers than peers. The way the State polices kids in this country at every level, the way authority figures here snap into aggression towards black and brown children, the way immigrant parents are bypassed when that happens, these are realities that deserve far more scrutiny than anyone on our so called No Fly Lists, which also include children some as young as babies.

The hypothetical situations of mass surveillance dragnets, the resultant insecurity and anxiousness, the increasing marginalization of difference, these are in fact not hypothetical and are already occurring. More importantly, people are finding ways to resist and continue living their lives carrying that knowledge and within these realities. There is more evidence of human resilience than there is proof of our doom.

The remove of pundits from these realities is so alienating. I don’t want to hear the prognostications of people who have no stakes, nothing to lose or at risk other than the nature of their next “viral scoop” or late night punchline.

There’s no room for metaphor in this country. Even suffocation can’t exist as a metaphor here, the idea of “I can’t breathe”—that is already a literal occurrence, we saw what that looked like through Eric Garner. America excercises so many extremes across culture that it is beyond being contradictory—it’s its own exaggeration. A white guy can come and fire a gun into your house of worship whether it’s a black church in the south or a Sikh temple. That happens already. But we also have religious freedom and people fighting to ensure that remains true. My parents would say they’ve achieved the American Dream, I would point to all the times our lives turned on the favor or displeasure of a white person. What do you do with all of these competing facts about the same place? The “American experience” is overwhelmingly atomized. The more my parents learn about what life requires of me and my brother and sister the more they’re starting to question just how easy a life immigrating here promised. But I’m grateful, living here was formative to who I am and I can’t regret that. Not often at least, regret can be as useless as nostalgia. The other day my mom said “I wish you could take a break from the American dream.” It was a funny phrase to hear, she was only partly joking.

Your departure to London was imminent before a new job opportunity at Viceland (Vice’s new-ish TV network) opened up. Can you tell us what your new job title and job is?

Right, their President of Programming reached out and asked what I thought of the channel. Now my job is answering that question full time. As Director of Development I help create new programming.

Our forthcoming late night daily show starring Desus and Mero is especially one I’m excited about. Think of how stagnant the late night talk show as a genre has been, it’s almost exclusively white men named Jimmy. There’s practically more turnover in the Supreme Court than in late night TV—the roles are handed down as ceremoniously. Making a TV show around Desus and Mero is just one of the moves that felt very clearly right to us at Viceland and shockingly, not to other channels that are also aware of the duo. It speaks to the history of the company, Vice is a brand born out of the impulse to find the people and places that give grit and texture to society, to report on culture. The culture contains a lot we’ve only just begun to put on TV.

All the stories on Viceland are stories about the way people engage with the world around them, it’s very point of view driven. And now there’s a sincere motivation to expand the range of views Viceland offers. The drive to go to people where they are, whether it’s a conflict zone or a party, is matched by an ability to meet audiences where they are, whether it’s on their phones or in front of their television, in America or abroad. That’s exciting. Viceland is very uniquely positioned with respect to what it can and is willing to offer the public. It’s been cool joining that process. We’re at a point in television’s history to challenge the implicit assumptions of the form, and no one seems as ready to take advantage of that moment as Viceland.

What kind of programming do you hope to bring to television?

I hope the new shows we create fulfill the attributes I look for in anything: Is it beautiful? Is it true? Television is a demand on people’s time and attention, I hope we can continue being worth both.

Beauty is the very least we can aspire to, and the access and power television offers certainly makes it a space worth valuing truth in. Are we being fair to the people we work with? Are we working with the right people? Who are we elevating and at whose expense? We’re constantly producing culture, is it decorating the landscape, accelerating a devolution of it, or ideally, ferrying audiences across towards a better future? That’s not to overstate the benevolence of a TV network, but to acknowledge the role media plays in our lives. Time moves forward regardless of what we choose to do with it, so what are we taking along with us? Everything put on TV is an insistence on values. It’s worth reflecting upon what those values may be. And anticipating where the culture is headed because we help shape that inheritance.

Television and movies. Do you watch a lot of them?

As much as anyone. I’m trying to get myself to watch more horror movies. Turning to horror for leisure never before appealed to me, some of us already live there. Horror is already such a dominant category of human experience that to reach for it as entertainment wasn’t something I had an appetite for. Just more violence you can’t bleach from your memory, only loop. I couldn’t really bear it. But I’ve grown to respect the artistry around fear and dread. To reproduce those feelings in a controlled environment takes skill, and requires understanding their origin points, that’s what I’m seeking. It Follows, Neon Demon, The Witch, they’re all very different from each other but had throughlines relevant to what I’m trying to understand about the world and myself right now. They shared an efficiency I’m interested in.

Those are all incredibly recent entries to the horror canon. If that’s your introduction point, you’re going to be disappointed soon exploring the horror category.

It’s the particular fears in these films I find compelling; paranoia, pre-emptive violence, it’s very American to me. I want to find out how much of this I can withstand. I’m curious about how attuned I am with dread and horror in American life, in my life. I’ve considered America from most angles, I understand the anxieties that make this country what it is. I’ve never gotten much sleep, now I want to know what keeps others up at night.