How Asian Americans across the nation are reflecting on their relationship to the Black Lives Matter protests

July 16, 2020

Six days after the brutal killing of George Floyd in Minneapolis, Eileen Huang, a junior at Yale University, wrote an open letter to fellow Chinese Americans, declaring the need to address anti-Blackness in Asian America.

She wrote that she’d witnessed anti-Blackness from her own relatives in the form of fearful warnings about Black neighborhoods and Black friends; that her community ignored the racial violence inflicted on Black Americans; and that “we did not gain the freedom to become comfortable ‘model minorities’ by virtue of being better or hard working, but from years of struggle and support from other marginalized communities.”

The letter, available in three languages, urged readers to learn from Asian American history, to donate to Black Lives matter organizations and to ask themselves, “Whose side are you on?”

In response, Lingfei, a first-generation Chinese reader in New York City, wrote a livid critique accusing Huang of “arrogance and conceit,” of failing to appreciate the sacrifices of her parents and community, and of regurgitating leftist positions to show off her own “‘political correctness’ and progressivism.”

He contended that parents warning their children about “problems existing in the African American community” were merely “tell[ing] the truth”; that Asians have experienced hardship “that far outweigh the burdens of African Americans” but yet never “wailed and blamed others,” and that African Americans had failed themselves.

Next came a response from someone born in China but educated in the U.S., responding to both letters under the pen name Mef Sufsuxbir: “To the elder generation of Chinese immigrants, I hear your confusion and your heartfelt disappointment. … your children seem to show no gratitude. They take for granted the peaceful and stable life for which you sacrificed much of your youth.”

Slowly and painstakingly, the writer began to complicate things. “But at the same time, we must ask: is hard work sufficient for a good life in America? Not quite.” The writer delved into the history of slavery, Jim Crow, the Civil Rights movement and mass incarceration, and undermined the model minority myth by pointing to high levels of poverty within some parts of the Asian community. The writer then called on immigrant parents to try to understand their children’s perspectives as people of color in the United States.

This dialogue—circulating on the Chinese social media site WeChat in June—is but one example of a wider phenomenon in the Asian American community that has accompanied the national uprising. Across multiple ethnic groups, many Asian Americans are engaging in sincere, difficult conversations about the Black Lives Matter movement and anti-Blackness in their own communities.

“I feel that this level of nuance and response to the political moment feels extremely different than the 2014 BLM, I mean specifically among the Chinese American community,” Melanie Wang, Chinatown Tenant Union lead organizer at CAAAV Organizing Communities, told me in a text message in June, referring to the Black Lives Matter uprisings six years ago. “There are many Instagram feeds and WeChat discussions popping up specifically oriented at talking through these dynamics.”

One Instagram feed, called “Send Chinatown Love,” recently began producing accessible Chinese-English storybooks to help immigrant families learn about the deaths of George Floyd and Breonna Taylor. That work is happening across languages: The Jakara Movement, a California-based Sikh organization, has produced a series of Punjabi explainer videos discussing concepts like the “School to Prison Pipeline.” There’s also Letters for Black Lives, originally launched in 2016, whose participants write letters to families about the Black Lives Matter movement and translate them into multiple languages.

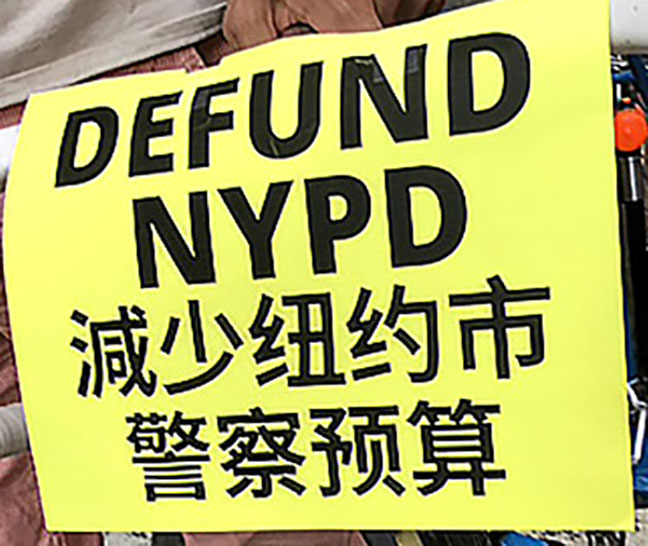

Some Asian groups are holding space for group learning: on June 11, the National Association of Asian American Professionals led a zoom conference, “Leading in a Time of Crisis,” at which board members discussed how to be effective allies to the Black Lives Matter movement and touched on what it means to “defund” the police, the problem with the phrase “All Lives Matter” and other answers to questions from their community.

Media personalities are also getting involved: Indian comedian Hasan Minhaj’s scathing critique of Asian silence challenged viewers to invest their time, energy, and professional skills into the movement. Even TikTok viewers had a chance to self-interrogate as they listened to Jenny Chang demand that Asian Americans “take that muzzle off—that muzzle your parents put on you as a god damn child!”

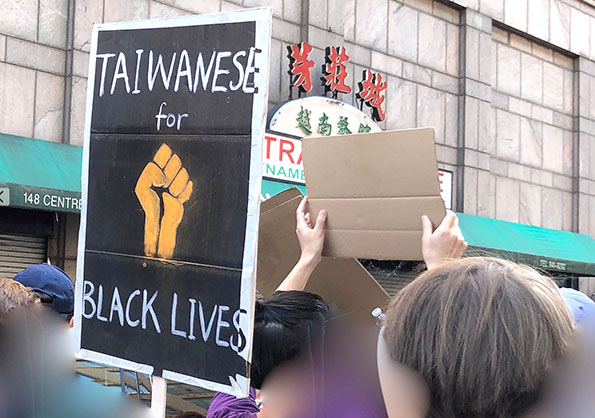

The nation’s multiracial protest movement has had an unignorable Asian presence, whether that be the Sikh American who took to the mic at a protest in Los Angeles; the Sikh groups feeding protestors at mass scale; the assembly of multiracial Muslim protestors who bent for prayer in the middle of Brooklyn’s Barclays Center; or the Bangladeshi family in Minneapolis that used their restaurant as a safe haven for protestors, even continuing to calling for justice after their restaurant burned down during the uprising.

This is not to suggest there exists a consensus among Asian people or Asian organizations on the many issues raised by the movement. For instance, when the Massachusetts Asian American Commission issued a solidarity statement that said Asians have benefited from proximity to white privilege and that the commission “acknowledged the deep roots of anti-Blackness” within the Asian American and Pacific Islander community, the co-founder of the Boston chapter of the Chinese American Citizens Alliance then publicly complained that the Commission’s language was “divisive and inflammatory,” and posed that, while the chapter also sympathized with the Black community, “in some ways, we suffer from discrimination more than Blacks.”

Meanwhile, members of an Asian-interest fraternity at NYU were exposed making racist comments on a group chat, including, “We grinded significantly harder while black peoples were lazy,” and, “the threat of police brutality keeps those communities more safe than without it.”

Many members of Asian America continue to buy into the “model minority” myth and into violent stereotypes of African Americans. Others continue to debate earnestly—as does our wider society—what it means to defund the police.

Recent discussion around the New York City Asians for Black Lives March, held on June 13, greatly exemplified these tensions: some Asian American activists took to social media to criticize the march’s organizer, the actor William Lex Ham, for appearing not to support abolition of the police as well as for his vocal support of a Chinese-American NYPD sergeant who was running for State Assembly in Queens and whose criminal justice positions the activists opposed.

Ham, for his part, said the march had nothing to do with his support for the sergeant’s candidacy, but was simply meant to bring together Black and Asian New Yorkers, and that he supported defunding the police and other reforms laid out in a Black Lives Matter Greater New York Blueprint and wasn’t staunchly “anti-abolition.” Ham also noted that Lee had exposed corruption in the NYPD (though Lee is also clearly more conservative than the incumbent he was challenging, Assemblymember Ron Kim).

These exchanges laid bare the ongoing debate within Asian communities about how to support the goals of Black Lives Matter if you have friends or family members who are police officers, whether the ultimate goal of the demand to “defund” is to abolish the police, and what is the role of Asian Americans in a Black-led movement.

Yet the fact that these conversations are happening at all signifies an important moment for Asian America. While these conversations are certainly happening for white families as well, many Asian families are arguably particularly sensitive to the moment given the White House’s recent anti-Chinese and anti-immigrant attacks.

“The Black Lives Matter movement has had a huge amount of support from Asian Americans of the younger generation; not so much from the first generation of immigrants,” said New York State Senator John Liu. “This time, however, there is a much broader level of support and understanding,”

“There’s an understanding that, in the first couple months of this year, Asians Americans, especially new immigrants, were the targets of much racism related to COVID-19, and the President’s reprehensible characterizations of COVID-19 as the Chinese virus. …There’s a realization in the Asian community that… we have been facing a huge spike of racism and discrimination. But we also have to realize that the kind of discrimination we face pales in comparison to the daily ordeal that Black Americans have to contend with,” Liu said.

Conversations about the Black Lives Matter movement look different across the diverse communities of Asian America. I spoke with leaders in just three of those many communities to understand some of the nuances of those discussions. These impressions reflect their thoughts during the first two weeks of June.

◻︎◻︎◻︎

High Anxiety in Manhattan Chinatown

New York City’s CAAAV Organizing Asian Communities, founded in 1986 as the Committee Against Anti-Asian Violence, organizes Asian communities to challenge systemic oppression in many forms, and has roots in anti-police brutality campaigns and coalition work. In 2015, it called for justice for Akai Gurley, a young unarmed Black man unintentionally killed by former NYPD police officer Peter Liang.

When Liang was indicted and later charged with manslaughter, many Chinese American politicians and professionals protested, arguing the officer was being made a “scapegoat” for the crimes of white police officers. CAAAV writes that for this decision, it faced “aggressive harassment and threats from right-wing Chinese American forces” and was also “met with tremendous challenges because of the extent to which working-class Chinese immigrants in our community and our membership base sympathized with Liang.”

(Liang’s conviction was later reduced to criminally negligent homicide, for which he faced probation and community service time.)

This June, CAAAV’s staff was early to issue a statement expressing support for the uprising, identifying systemic racial violence as it affects Asian Americans and other communities of color, and acknowledging that “Anti-Black racism is deeply internalized in many Asian communities.” Yet CAAAV organizer Wang acknowledges that within CAAAV’s larger base of immigrant members, there is a wide mix of feelings about the protests.

“What I’m hearing from them is complex. There is solid support for the protests, but also fears of looting and questions about what it will mean to defund or abolish police,” Wang texted me on June 10.

“Their perspectives are informed both by their eyewitness experiences and by global geopolitical perspectives, which bring really complex dynamics – e.g. Hong Kong protests, [Chinese Communist Party] critiques of race in the U.S.” Chinese mainland commentators have been calling attention to the United States’ “double standard” when it comes to human rights abuses in its own country versus abroad.

CAAAV’s base is divided on the Hong Kong protests and whether that rebellion is worth the impact that it has on the daily lives of working-class people, Wang said. Some of those same concerns are being expressed about the Black Lives Matter mass actions. During the first week of protests, reports of lootings and fires in Chinatown and neighboring areas frightened some members of the community.

On WeChat, CAAAV members re-shared warnings: “If the demonstration turns into a riot, Chinatown will become the main area to suffer damage,” one read. They also circulated videos: of a fire on Mott Street, of looting wreckage in SOHO, of a speech, subtitled in Chinese, from the president of the Police Benevolent Association of New York State, and others. “The Black people have started making a mess…It’s dangerous, several thousand people,” the maker of one circulated video reports in Mandarin.

“The fear that is associated with that is coming at a very hard time for the community,” Wang told me during the first week of protests. “Chinatown folks that we work with have already been staying in their apartments since January …The neighborhood is hyper-vigilant about COVID-19, but also folks didn’t want to go out because they were afraid of being targeted,” by anti-Asian violence.

Wang added that, as a result of a history of neglect of the Chinese American community, there’s a sentiment that government “doesn’t stand up for Asian Americans, or doesn’t stand up for Chinatown, or is willing to leave folks out.”

Chinese New Yorkers are easily mobilized into a state of outrage, she said, “using the idea that we should not be walked all over.” The challenge is acknowledging this frustration and ensuring that it helps to build, not hinder, solidarity with other oppressed groups.

CAAAV seeks to build these bridges by emphasizing linkages between police violence and other forms of systemic violence that Asian communities are already battling. “We are fighting right now for rent cancellation, and that takes funding,” said Wang, speaking of the Housing Justice for All Coalition’s campaign to cancel rent in New York State for the length of the pandemic emergency. “We are fighting like hell for those demands, but in a city that spends $6 billion of its budget on the police, how much is left for anything?”

State Senator John Liu, who stood with former officer Peter Liang’s family in 2015 but has also marched with protestors and pushed for police reforms this June, said he still stands by his original position on Liang, and says it was widely felt in the Chinese community that Liang was treated as a sacrificial lamb for the NYPD. He also said that the events of history have shaped public opinion toward a large police presence, with many New Yorkers supporting a highly equipped police force after the 9-11 attacks, but that people are now waking up to the “inherent racism in the police system” and are appalled by the violence against protestors in this year’s uprising.

“Some of the tactics used just seem anachronistic in this day and age—kettling people, clubbing them, controlling people using intimidation tactics, and the use of tear gas and other weaponry that are meant for foreign wars, as opposed to your own citizens,” Liu said.

Of course, the NYPD’s surveillance of Muslim New Yorkers following 9-11 was also one of the most visible demonstrations of police violence in recent history; activist Linda Sarsour once described it as “psychological warfare” against her community.

◻︎◻︎◻︎

After Tou Thao, in Minneapolis

The image of Hmong Minneapolis police officer Tou Thao turning his head away as Derek Chauvin presses his neck to George Floyd’s neck has become, for many Asian Americans, a symbol of the Asian community’s silence on matters of injustice. For Minneapolis Asian Americans themselves, the moment has also been one of conflicting perspectives.

The New York Times reported that one Hmong business owner whose store was damaged during the fires in Minneapolis has become “as scared of Black Lives Matter as of the police,” and that the community is divided on how to view the uprising, with younger generations more likely to side with protestors. Some Hmong in Minneapolis have said they felt attacked for the actions of one member of the community.

Bo Thao-Urabe, the executive and network director of Minnesota’s Coalition of Asian American Leaders, said it’s true there are different perspectives, but that she’s also been impressed by the swell of activism in her community. “I saw so many people there…Latinx, Asians, Hmong, white people, Black people all really working together to both bring food and supplies, but also to support each other and to go off on assignments together to continue to build their communities. And they were self-organizing …. they just knew [what] they had to do.”

Many Hmong families came to the United States as refugees and the population has a lower median income than other Asian populations in the U.S. Their story is a clear example of the ways that the “model minority myth” erases the experiences of some Asian Americans and serves to obscure systemic inequities. A Minneapolis Hmong family suffered the police killing of their 19-year-old, Fong Lee, in 2006.

While living alongside other marginalized groups can sometimes be the basis for cross-racial class solidarity, it can also create challenges. “We understand what it is to be excluded and to know that pain, but I think that building that, and landing in those neighborhoods, doesn’t mean we understand the history of racism in that country,” Thao-Urabe said. “Because our communities are often pitted against each other in these poor neighborhoods, it means that people are fighting for resources and there’s tension there.”

Thao-Urabe also said it isn’t always true that the younger generations are more understanding of the uprising than older generations.

“The elders who suffered through war and were part of uprisings can understand why Black people are so angry about the injustice and why they’re rising up to fight for their freedom and liberation—because that’s what our parents did when they were being oppressed,” she explains. Some younger Hmong, she said, feel the impacts of systemic racism, but also may not be fully aware of the history of white supremacy in America. “Their pain was not acknowledged, and people don’t understand that they too suffer, so they [think of it] like either—’choose our lives or choose Black lives.'”

The Coalition of Asian American Leaders and a group of other Minnesota Asian organizations issued a joint statement after the death of George Floyd that sought to both recognize the pain in the Asian community and call for solidarity with the Black community. They noted that the involvement of Hmong police officer Tou Thao in the murder of George Floyd is “yet another reason that we must recognize our silence in the face of anti-Black racism.”

They also wrote that “as Asian community members are targeted and businesses are damaged, our communities are in pain”—a sentence that subtly acknowledges the civil unrest that damaged Hmong businesses, but also more broadly, the impact of COVID-19 and decades of systemic racism. By June 11, the letter had been signed by over 340 Asian American organizations across the country.

“That pain is not just about the uprising, it’s a larger systemic condition that ignored them, that wasn’t working for them anyway,” Thao-Urabe explains. “Whether that was limited English speakers who were not getting information that they needed, or small businesses who were being left out of relief packages … and disproportionate health impacts for people who are …essential workers….We can’t talk to our community without already acknowledging that there were already a lot of disproportionate outcomes.”

◻︎◻︎◻︎

Los Angelenos post-1992

The events of the 1990s continues to shape the relationships between Asian and Black communities in Los Angeles today—the killing of Latasha Harlins, a Black ninth grader, at the hands of a Korean shopkeeper; the brutal beating of Rodney King by police officers, and the civil unrest that followed, causing severe damage to Koreatown and the loss of many lives across the racial spectrum.

“There are communities there that take that to heart and became very bitter about it, and [came to an attitude of], ‘we don’t trust African Americans,'” said Abraham Kim, executive director of the Council of Korean Americans. Others, he said, “took that experience and identified that as: we need to do better and we as a community cannot just be internally focused, we have to build bridges.”

Asian American organizations and Black-led organizations have worked to create partnerships in the years since. Asian Americans Advancing Justice – Los Angeles, for instance, has relationships with the local chapters of the Urban League, the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, and others. In 1991, even prior to the unrest, Advancing Justice – LA launched Leadership Development in Intergroup Relations, a leadership and inter-ethnic relations program. Yet budding inter-racial bonds between activists and community leaders aren’t always felt by everyone on the ground.

“There’s a certain strata of Asians and Blacks who have really worked together closely … but in terms of the community, I would say there’s a mixture of misunderstanding that still remains,” said Stewart Kwoh, founder of Advancing Justice – LA. (Aileen Louie, interim co-executive director of the organization, note that some Asian communities, especially some Pacific Islander communities that often live alongside Black and Latinx communities in Southern California, already have stronger cross-racial alliances. It would also be amiss not to acknowledge the growing number of Americans who are navigating the lines between this binary: almost 250,000 people in the U.S. identify as both Black and Asian or Pacific Islander, according to the 2018 American Community Survey.)

Both Kim and leaders at Advancing Justice- LA described the current moment as one of soul-searching—of Asian Americans realizing, especially in the wake of recent anti-Asian attacks, that they must also take action to confront anti-Blackness in their own communities and in the nation at large, but still discovering what form that action will take.

Advancing Justice – LA has called for the prosecution of the officers who killed George Floyd, redefining the institution of law enforcement and investing in Black communities. It’s also thinking about how to grow new partnerships with more recently formed Black Lives Matter organizations, how to successfully collaborate across races during the next redistricting cycle and in the fight for voting rights, and how Asian Americans can become more involved in police and criminal justice issues.

Advancing Justice – LA and many others I spoke to also emphasized the necessity of requiring ethnic studies education courses in schools, noting that many Asians don’t even know the history of their own communities in the United States, let alone the struggles of Black Americans.

” [There is a] superficial understanding of how all of our pathways and journeys are very much interlinked because of civil rights, because of being a minority in the United States, and how the Black community has stepped forward to help the Asian community,” said Kim.

He also argues that challenging the “model minority” myth is not only right, but the only way Asian Americans will be able to break their own glass ceilings. The truth that many Korean Americans are beginning to realize, he said, is that greater political power in American society will require not only the values of hard work and focus espoused by many immigrant parents of every race, but also knowing how to develop strong relationships in a multicultural society.

“It [isn’t] just about studying hard. Not just about getting good grades…it ha[s] to be hand in hand with building bridges and building community with other groups,” Kim said.

“We have to stand together with other communities because we all have to work together.”