In a collection of poetry and prose, writers respond to the work of Bengali photographers exhibited in Eyes on Bangladesh

April 25, 2014

Late last month, the work of nine prominent Bengali photographers were brought together in a special exhibition in New York City organized by Eyes on Bangladesh, an initiative founded by a group of Bangladeshi-Americans that not only hopes to bring light to representations of Bangladesh we rarely see in the US, but also to inspire a dialogue between first- and second-generation Bangladeshis.

On display from March 26-30 on the third floor of Queens-based SoundView Broadcasting, a media company that brings some of South Asia’s most popular television channels to homes across the US, the Eyes on Bangladesh exhibit was host to a series of public events to celebrate its run, from a screening of a documentary film on the artistic and cultural production borne out of the Bangladesh Liberation War of 1971, to a moderated discussion between immigrant parents and second-generation children. Painstakingly arranged on the walls of the space were powerful and captivating photographs by the nine photographers: Shumon Ahmed, Taslima Akhter, Rasel Chowdhury, Shamsul Alam Helal, Jannatul Mawa, Saikat Mojumder, Sarker Protick, Rashid Talukder, and Munem Wasif.

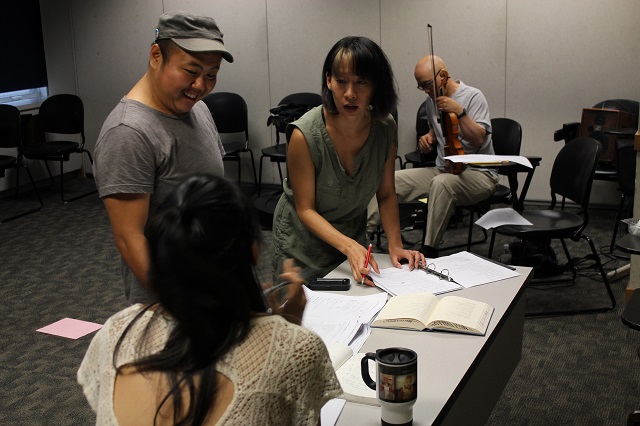

As part of the series of events, the AAWW invited eight writers to each respond to the work of a photographer featured in the show, using a single photograph or a set of photos as a prompt for original creative work.

Writers are often asked to talk about the inspiration behind their work. Rarely, though, are we witness to the encounter between a writer and an object from which their work springs—to watch as the object is brought back into conversation with the work it inspired.

On March 29, standing before the photographs they chose to respond to, eight writers read their pieces aloud. It was a meeting of art forms, a collection of countless visions into one, yet also a refracting of single images into many.

Their pieces spanned genres. Some called on historical events or recalled personal anecdotes, while others animated characters caught within the photograph’s frame. The writers were not provided with any information on the photographers or their work prior to the event, but in keeping with the concept behind the exhibition, they each gave us a new way to look at Bangladesh.

The pieces follow in the order in which they were read:

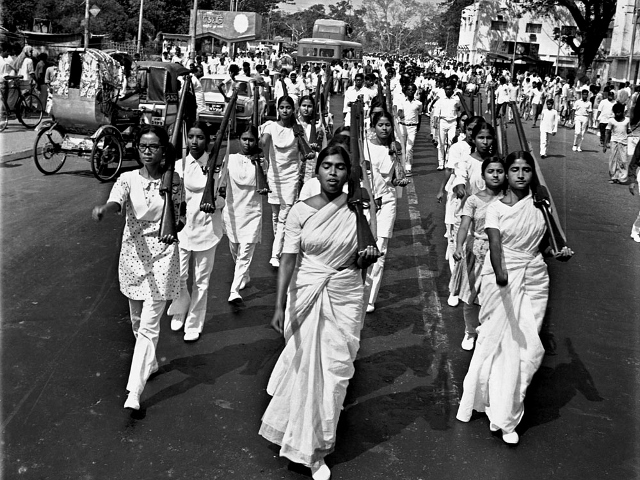

1. Celina Su – Rashid Talukder’s Untitled

2. Sunu P. Chandy – Jannatul Mawa’s Close Distance

3. Alaudin Ullah – Saikat Mojumder’s LIFE: Born in a Slum

4. Jordan Alam – Taslima Akhter’s Death of One Thousand Dreams

5. Wah-Ming Chang – Sarker Protick’s Of Rivers and Lost Lands

6. Sunil Yapa – Rasel Chowdhury’s Desperate Urbanization

7. Meera Nair – Samsul Alam Helal’s Love Story

8. Faheem Haider – Shumon Ahmed’s What I Have Forgotten Could Fill An Ocean, What Is Not Real Never Lived

Celina Su

Rashid Talukder’s Untitled

Swami Youth League, March 1971

In honor of Rashid Talukder

The difference between a language and a dialect is an army.

– Max Weinreich

Between east and west, a thousand miles, and yet, our figurative divide looms longer. We do not wear white to declare our independence, nor mourning, nor innocence, nor to beg for color, but geometry—that there be a governmental structure to call ours, a language with which to communicate axiomatic grievances, these parallelograms of desire.

For I march in the back row,

yearning to leave my home, to have a sense of it,

to call out a name for it. To relish the righteous weight

of my rifle, a border in the shape of my belonging.

For I am the bespectacled one,

a bit older than the rest.

But secretly, I came from the south.

But even more secretly,

I walked from Arakan,

speaking Rohingya,

then Chittagonian,

then Bengali.

For I am the one who stands

shortest.

I will leave,

return as a grandmother,

flying from London to land in Kolkata,

to travel to my family house across land, for the semblance of a contiguous Bengal

whooshing

beneath

my cracked soles.

For I proudly

take the lead

of the center column,

singing in the wide boulevard,

a soft but clear note that travels,

announces our intentions

across our national imaginary.

For in three days, I will

turn nineteen.

For I wish to study developmental psychology,

to become a mechanical engineer,

to marry young,

to recite the lines of Rabindranath Tagore.

For in nine months—

the equivalent of a university year, of antepartum gestation—

on December 14th,

I will witness

Indian air strikes against Dabar Hall.

Two days later,

the Pakistani army

will decapitate my uncle

at the Rayer Bazaar.

For in response, Kaderia Bahini members will bayonet collaborators, slowly, on a grassy field. For what makes a nation, but bearing arms, but wearing the same absence of hue, but a tessellating manifesto in the form of a 6-pointed star. Who bears witness to this weapon of sudden red hot power, wherein the whole is greater than the sloping tactility of its parts. And in the stead of a linear progression, between government and governance, these smooth, symplectic manifolds.

(In a true revolution, I am told, resolutions are asymptotic.

For I am the photographer; I possess two eyes. They aim to become yours, and yet— if you were to close your eyes, as if to see—Between these drawings of light, I will be beaten by the very police officer I had rescued from an angry mob just a few years before. I will keep these secrets for two decades, and then. Let this be the anti-Dante, a visceral appositive to Paolo and Francesca—If not quite immortality, then the moment in which dying becomes an eternal act.)

was born in São Paulo and lives in Brooklyn. Her writing includes a poetry chapbook from Belladonna*, three books on the politics of social policy and civil society, and pieces in journals such as n+1, Aufgabe, and Boston Review. Her honors include the Berlin Prize and the Whiting Award for Excellence in Teaching. She teaches political science at the City University of New York and co-founded the Burmese Refugee Project in Thailand in 2001.

Sunu P. Chandy

Jannatul Mawa’s Close Distance

Hey, Thanks for Being Nice (what the Whole Foods grocery delivery guy said to my friend Pia)

1.

When the back of the house

kitchen staff at Ollie’s pulls up a seat

in the front area of the restaurant at 89th and Broadway

and starts snipping off the ends of 1000 green beans

in my exact line of vision, do I suddenly feel less at ease

sipping hot and sour soup on a cold winters day? You can say

to oneself, but wait, I am not like these other white

customers but wait, I practice

labor law, but in the end we are sitting together

in my living room, on my sofa and I just paid

you to make lunch and somehow my conscience

feels better when your work is behind

that restaurant wall, when some sheetrock

lies between us.

2.

In my Brooklyn elevator when the nanny asks

which family in the building

do you work for, I feel shame,

pride, a strange sense

of solidarity as I grip my own

adopted daughter’s hand tightly. Is it because

I see you? Is it the brown skin? Is it the smile?

Is it something about my blood becoming

recognized. Like the time someone visited my parents

in their home for one day and then thought

for some reason to ask me if my father’s family had less money

than my mother’s. Yes, my Amma’s family home has rubber

trees on one, two, three sides but alas inheritance passes

through only the sons despite Mary Roy’s court case.

3.

In the small Ohio village my Amma made

all of the kape, all of the chai. I would watch her

take a spoonful of each one to taste it

to ensure the proper sweetness for each guest

before placing the china cups on a tray to carry out

to the church visitors alongside imported

banana chips and American-store-bought biscuits.

4.

Age ten in my aunts’ Kerala kitchens in that capital city

of Trivandum, I always wanted to take a turn,

sitting on the floor and straddling that coconut

scraper. Scrape, scrape, scrape. Leaving much too much

coconut meat in the shell but the kind helper still gave me

that Good job for an American girl head nod

and smile. But after the first ten scrapes the work turns

to pure drudgery. When I got up and skipped away

you took your seat again both legs swung to one side of it. I move on

to the mortar and pestle pound pound pounding the spices for a few beats

and then retired to the sofa or the bedroom

for the rest of the afternoon reading

every single one of the Reader’s Digests in my aunt’s glass

cabinets. Somehow by evening the rest of the coconuts were all

shredded and appeared in the green bean thoren. Auntie says

look Sunu, this was your work, do you see

your coconut there in the dish? You did such a good job helping out

in the kitchen this afternoon.

5.

In the Kerala village, I watched Ammachi

on my Dad’s side use the fibers from baby

coconuts to keep the fires going. She killed

one of their chickens from the backyard

on the occasion of the last day of our visit

from America that summer when I was nine.

6.

In Lower Manhattan I give the new

cleaning lady various gifts in exchange

for taking out the garbage

from my windowed office. First an almond

pastry from Financier,

then an apple from the green market, then three pairs

of gently used dress shoes. She takes them all

with a smile, but we have yet to remember

each other’s names.

7.

Wonder where I first learned this rule: You must stand

when the judge enters the court room. One afternoon I watched

the senior law clerk run back to her desk to put on her suit jacket

before going to the judge’s chambers and in that

moment I learned all I needed to know in law school.

The founder of Quakerism was jailed

for not bowing down before the king

in the name of equality and here I am,

a birth-right Quaker, standing up, every time

a federal judge enters the courtroom, for the past

15 years. Pound pound on the door, All rise. You may be

seated. Good afternoon counselors. Good afternoon

Your Honor. These practices we accept

as commonplace, as commoners. The Judge always wears

her black robe and I always remember to wear my suit jacket.

8.

When I arrive home two hours later I am still

wearing my suit jacket and our baby

sitter is wearing sweat pants

though all of hers have her college’s

name written down the side of one leg.

9.

Before we left Delhi to take the baby to see the family in Kerala

we took all of our left-over rupees into Rohini’s mother’s

kitchen. How else to say thank you for all the meals brought to us, literally

on a double-decker cart, rolled into our room. This room where we lay,

in shock, with a newly adopted baby on the floor. You brought chapathis,

dal, rice, thoren, curries, pickles. We left the kitchen staff

with only a sequined silk purse from FabIndia and

whatever rupees we had left over

after two days spend shopping in Delhi. The helper girl was wearing red

rubber chapels, I was wearing navy blue tennis shoes. We did not ask

the madam of the house permission before going into her kitchen.

10.

When my cousin and her husband cut into their wedding cake

during that moment when they put both their hands on one knife and

looked up and smiled they had their backs to me. I witnessed

one of the catering ladies take Dan’s arm

and put it swiftly around Vidthya’s waist

with a movement so quick and so slick and so

routine. I do not know this invisible woman’s name

who works at the most light-filled

wedding venue in all of downtown Madison

but it is only because of her that the photograph

on the front of their wedding thank you card

that came in the mail last week appears just so flawless.

has devoted her 15-year legal career to working for civil rights in the labor and employment context. She serves as a Senior Trial Attorney with the United States Equal Employment Opportunity Commission’s (EEOC), where she litigates employment discrimination cases in the public interest. Sunu completed her MFA in Creative Writing (Poetry) in May 2013 from CUNY – Queens College. She has served on the Boards of Directors of several NYC organizations including the Audre Lorde Project, LeGal (the LGBT Bar Association), and SAWCC (the South Asian Women’s Creative Collective). Previous publications include work in the Asian American Literary Review, the Poets on Adoption blog, and in This Bridge We Call Home: Radical Visions for Transformation.

Alaudin Ullah

Saikat Majumder’s LIFE: born in a slum

Hands

When I was selected to pick from a group of pictures, I couldn’t stop staring at the one of the woman sitting in front of pots Indian style. It reminded me of my Grandmother and Aunties in Bangladesh. This was a place that they were truly free, where no one could control them. A place where they were empowered. Where they were just as artistic as any artist. Where they created and innovated. This is a place where first generations Bangladeshis, like myself, seem to have amnesia about. Food can help us find home when we are lost. Food brings us back to our mothers.

***

My friend was throwing a party. It was a social dinner with academics, lawyers, doctors, artists etc. My mother would refer to them as “big shots.” Everyone was to bring an ethnic dish. I got to this United Nations Pot Luck after a show. The apartment was packed. I made quick introductions and then used my Spidey Sense to locate the kitchen. I have a love affair with food. It’s an addiction for me, along with the Yankees, Knicks, and Marvel Comic Books. In the Kitchen I’m as focused as a Ninja. The smells have led my growling stomach to a diverse spread of foods. Smiling like a dude who just hit Lotto, I prepare a plate of Rice and Beans, Lamb curry, Collard Greens, Jerk Chicken, and Shrimp Dumplings. Looking at my stomach, you can tell I’m not shy about eating so I don’t mind stacking my plate as high as the Empire State Building. Bangladeshis love to eat.

In the 1940’s Mahatma Ghandi announced he would be going on a hunger strike for peace. Giving up food would be his way of raising awareness for the plight of India’s liberation from the British. My father told me that everyone in his village of Noakhali said “Good luck bhayia (brother) we ain’t giving up Lamb briyani for No One! Hala Beta! I need my curry!” Bangladeshis have a long legacy of being passionate about COOKING and EATING! FOOD IS PART Of OUR SOUL!

I finish packing my plate, and am told, “We don’t have any more forks. I will look for a spoon for you.” With my plate, I found a seat in the living room. I was oblivious to the noise and talking around me. My focus was this food from different countries, aromas from different worlds. As I ate and relished the food, it grew extremely quiet. Everyone was staring at me. I was eating rice with my hands. One person approached me: “ Hi, we’re like wondering, where are you from?”

I was the first one in my family born in America. I was born in a Jewish Hospital, in Spanish Harlem, to devout Bangladeshi Muslim Parents. One of the first Muslim Bangladeshi families in Spanish Harlem, we were the Addams family of the hood. You wouldn’t know it was 104th street if you visited our apartment. My dad constantly chewed paan (a leaf with chewing tobacco) and wore lungees (which looked like a dress.) He got me one: “No thanks pop, I don’t want to be seen wearing a dress in the hood.” There were pictures of Mecca, The Bangladesh Flag, old pictures of my mom and dad in the capital Dhaka. You could smell the curry in our house from across the street.

You had to take your shoes off upon entering our place. My mother would mess my head up with verbal judo chops.

“Alaudin take your shoes off! Do you want Allah to take away your feet?”

“Well ma–”

“Shut up!”

My mother was notorious for asking me a question and NEVER allowing me to answer. To this day, I have never worn shoes inside her house fearing that Allah will confiscate my feet. We had plastic on our furniture. I used to love taking my shirt off on hot muggy summers to feel it stick to me. I’d get up and this feeling of plastic peeling off my back was like music to my skin. Only part of the house that was not Bangladeshi was my bedroom. On my wall were posters of Luke Skywalker, Reggie Jackson, Bruce Lee, Spider Man, and Jamie Summers, The Bionic Woman. As a child, I was madly in love with the Bionic Woman (this was late 70’s people). Men wanted an exotic woman, I wanted a bionic woman.

We were not rich, but my mom cooked like we were millionaires. We had the kinda wealth Donald Trump couldn’t buy. Food was our salvation. Cooking was my mother’s passion. As a little boy coming from school I could smell the curry from crosstown. I was the youngest, I used to stand on a chair to watch my mother cook. It was like watching Picasso paint. She never bought spices from the supermarket. Ever! Her holdee (turmeric), chili powder, jeera, chutney, masala all were made from her hands. She’d say, “if you buy it in a bottle it’s artificial junk.” She never cooked with it.

We would go to 28th street and Lexington Avenue better known as Little India, Curry Hill, to get her ingredients. She talked to everyone there. My mom couldn’t speak English well, but she knew all the languages from South Asia. Her native tongue was Bengali but, she could speak in Hindi if the person working was Hindu. She’d Talk Urdu if ladies in the aisle talking about recipes where Pakistani. She also spoke Tamil, Punjabi and Gujrati. My friends still tease me today: “Aladdin, how does your mother speak multiple languages while you butcher English?” My mom loved the art of shopping. I did not, because she would haggle ALL the time! Over every price! She would negotiate by shouting: “$5.99 a lb for chicken? $7.99 a llb for tilapia Deck so! A dey Allah! Do I look like Rockefeller! Give me a lower price brother.”

You never think your parents will rub off on you. I’m from New York and NOTHING like my mom! Yet decades later, I go to Whole Foods and end up shouting, “$21.99 a lb for Shrimp? $24. 99 a llb. For Salmon? Ah dey Allah! Deck so! Do I look like Rockefeller? Give me a lower price brother!” Bangladesh was where my parents came from. I am a quintessential American. I’m a Yankees fan from New York, A Knicks fan. I like Reggie Jackson, Patrick Ewing, Derek Jeter, yet Noakhali is in me.

When he was a young man, my father owned his own restaurant. Bengal Garden on 46th and 8th ave during the late 1940’s and 50’’s. He was part of the first wave of Bengalis that arrived in Harlem and pioneered the Indian restaurant industry. He and his fellow Bengali dishwashers were crazy men. I’m talking real crazy, batshit cuckoo for Cocoa Puffs crazy! They couldn’t read or write Bengali. No one rolled out red carpets for these illiterate immigrants like my dad. None of them could speak, read, or write English. Many of them were merchant seamen who jumped ship. Undocumented illegal workers who did something radical. Arriving in New York, which was already damm near impossible, what was their bright idea? “I’ll own my own restaurant.” I would love to see that discussion in banks today:

“Do you have collateral?”

“No.”

“Do you have any experience owning a business?”

“No!”

“Do you have a business plan?”

“No!”

That’s like me going to the North Pole and opening up an outdoor Barbecue restaurant. Crazy! In those days there was no demand for curry, no Little India, no Curry Hill, nothing. Just a small group of dishwashers with the dream that New Yorkers would love this amazing assortment of meat, vegetables, and spices from Indian villages. What they knew how to do was COOK curry! So my dad and his Bengali comrades did it. He opened his restaurant. He tried to teach my mom how to cook a fusion of Bengali and American food but she resisted. She wanted no part of any fusion. She told my dad, “I’m from Noakhali. What I cook is Bangladeshi. They will learn to love it! My children will know where I am from – (proudly) District Comilla, Mirawish Pur, Noakhali Bangladesh.”

My mother would serve Biryani (Rice based dish) and my Black and Puerto Rican friends would say: “Yo Aladdin, where’s the forks? How we gonna eat?” My mother would say in her broken English, “You no need forks to eat rice! (Gesturing) Eat rice with your hands!” She would explain the process like Robin Williams in Dead Poets Society. You could feel her passion: (demonstrating) “Mix the rice together with the meat. Feel the rice in your hands. Smell the rice! Taste the rice! Don’t be scared. Do it!” It was like Yoda was in our kitchen! My friend Carlos challenged mom. “Miss Ullah, my mommy said that you should always eat with a fork. It’s good manners.” Mom responded, “ In MY house you don’t need fork! Why you need metal thing in your mouth when you have hands?” Mom taught my friends: “The hand swoops, and the fingers picks up the rice. The thumb brings the rice into the hand. This technique demands patience and diligence. It connects you to the motherland of Bangladesh. Once you’ve mastered how to eat with your hands you’ve become an unofficial official Bangladeshi. That’s the way you had to eat it in my moms kitchen.

Now before we ate, we had to do a prayer. After about a year, my next-door neighbor knew the whole thing. A six-year-old Puerto Rican named Paul going “Bismillah hero man a roheem.” Puerto Ricans, Dominicans, African Americans, West Indians- everyone was doing Nomaz at our dinner table! All my friends, and my brother’s friends (Who are now in their late 30’s and 40’s) still know how to do Nomaz. Kids from different worlds showing solidarity because my mom taught us this ancient custom. Once you ate my mom’s lamb curry you would levitate. It became normal for my homeboys to find their way into my mother’s kitchen after a game of basketball.

When I was a kid we went to Bangladesh. I met my relatives. To say I stood out would be an understatement. They never saw anyone from America. They stared at me like a Monkey in the Bronx Zoo. My brother and I brought our baseball gloves and a basketball. When we tried to get our cousins to play, it was like showing my dog the latest iphone. It had no clue. Bangladesh was all trees, woods and no bathrooms, or no toilet paper. I complained to my father. He smacked me on the head and said: “Stop acting American!” My mom said: “You are spoiled!” Noakhali made the South Bronx look like the Hamptons.

Everyone in Noahkali says to me that I have to marry a Bangladeshi girl. I was only 8 years old! My mother explains what an arranged marriage is. The parents find a suitable girl for their son to marry. She informed me that my wife will come from Noakhali. “Nah ah amma! “Not me,” I say defiantly. “I’m going to marry the Bionic Woman.” At that time, the Bionic woman was the coolest woman on TV. Saturday nights I sat in front of my TV watching my future wife. She would run with her blond hair blowing in the wind, She jumped on and off buildings, dodged bullets and beat up bad guys. I knew she would wait for me, since she was Bionic she wouldn’t age.

“Does she know how to make lamb biryani?”

“But ma–”

“Phagul beta!” (Crazy fellow) She smacked me on the head. “ You will marry a Bengali woman so shut up! No more talk! Zoot karay!”

In my mom’s village, I saw her sit Indian style and cook with her mother. It reminded me of the New York Knicks. Before a game, you could see the team practice. They do a drill where one line shoots layups and another line rebounds and passes the ball. I loved this! The two lines flowed like poetry. It was the aroma before a meal. In Noakhali all women who cooked were like jugglers. Sitting Indian style, they would cook Rice, Roti, Lamb, and vegetables all at the same time. Multi tasking was in their blood not mine. When I try to cook eggs and toast…both burn. Watching them was like ballet at Lincoln Center, or the Knicks during the layup line, it was poetry before my very eyes.

Today my mom has rheumatoid arthritis. It’s an autoimmune disease that affects the joints. She has difficulty standing as well as using her hands. She hasn’t cooked in a long time. This past summer I asked her: “amma can you please teach me to cook Biryani?” She laughed, and then looked at me like Darth Vader.

“Why Alaudin?”

“Every time I try to cook lamb it tastes like a football and the rice burns.”

She is now in a wheelchair so her mobility is limited. When I wheeled her into her kitchen she moved like a Broadway dancer. It was like watching Lebron James on the basketball court. She was back in her element. She took out onions and with lighting speed demonstrated.

“This is how you cut onions. No big pieces. Get the garlic, get the holdee, and get the jeera. Stop buying spices, stop being lazy. Make them. There is magic in them. From the supermarket they are junk. Do you want to eat junk Alaudin? Your problem is you are too American. If you had a Bengali wife you wouldn’t need to learn how to cook this.”

“Don’t worry ma, the Bionic Woman is still waiting for Me.”

“Everything’s is a joke huh? Everything is funny to you huh? Mr. Comedian.”

“Ok c’mon ma, stop sweating it–”

“Alaudin I am not sweating what you mean sweat?”

“No ma it’s just, well never mind, just relax.”

There was a brief silence as she looked at me like and right through me. She was still an adult, one step ahead of the child she was looking at.

“Does my son know who he is? What do you want to do Alaudin?”

“I’m not exactly sure”.

In her wheelchair my mom smiled. She wiped the curry off of her hands, and said: “all your life you tell me who you are not. Who are you?”

For once she let me finish without cutting off my answer.

***

At the party, more and more people introduced themselves to me. They asked:

“How do I eat rice with my hands?”

“No, we really want to know.”

“Where are you REALLY from?”

I wiped my hands with my napkin, which by now was soaked with curry and food from all over the world. “I’m from District Comilla, Mirawish pur Noakahli Bangladesh. Land of beautiful spices, wonderful traditions, and Bengali speaking people who LOVE to eat with their hands.”

was one of the first South Asians to appear as a stand-up comedian on national television, on channels including Comedy Central, BET, MTV, and PBS. Alaudin later joined as an inaugural member of the Public Theater’s Emerging Writers Group, where he developed his solo show “Dishwasher Dreams,” which has since been in festivals and workshops such as “New Works Now!” at the Public Theater, The New York Theater Workshop, New York Stage and Film, The Cape Cod Theater Fest, and Silk Road. His journey researching his father for the solo play was incorporated into Vivek Bald’s Bengali Harlem (2013, Harvard University Press). Alaudin’s voice was recently featured as the character of Hanuman in the award winning animated film Sita Sings the Blues.

Jordan Alam

Taslima Akhter’s Death of One Thousand Dreams

The old cotton bag was tucked away at the back of my closet with all of the other broken unfinished things. When one of my chachas brought it with him from home, I had already known what was inside, folded carefully with the pattern facing inward to keep it from wear.

I unzipped the liner; it was cool between my fingers.

I spent every winter break on the phone with my mother. All of my other seasons were claimed by school and my father. I had been marooned on this island for six years, ever since my father won the lottery for a U.S. visa and borrowed money to set up a shop in Manhattan. On the phone with my mother, I mixed in more and more English words with Bengali every year.

“You have to come back soon. I don’t know what you look like anymore, ammu,” my mother would say every time.

My father had framed a picture of her and put it up in the small entryway to our apartment, so that I would never forget. It was printed on plain paper in black and white with creases at the edges. But I never believed that the woman sitting there was my mother; the woman in the photograph never smiled and was forever a new bride with her hands folded and covered in mehndi.

My mother was a maker of things. Her hands were small and thin and so dark that people would remark about the fairness of my skin in comparison to hers. They are very rarely still.

When I was younger, I wanted my mother’s hand – their creases and folds – but mostly their skill. She would come home and chop onions on the bhoti, and when the power went out and everyone lay down to sleep, I would still see the outline of her hands bent over the blade. When I want to cut anything, I can only use a knife.

It was spring now and we had put away our winter things. It took me several days to go digging for the bag. I scrunched the fabric as I lifted the quilt and spread it out across my bed, just staring. My mother’s tiny thorough stitches zigzagged over the fabric in greens and golds. I traced my finger over the smallest leaf as it sloped upward, melting into the other leaves, these red and brown against the dark blue cloth.

I had seen the news from afar, in glimpses of articles sent around by friends and 15-second news clips on the British television networks. And then there were all the calls. My father’s friends calling to check in, chachas and chachis from all over the States, people we hadn’t seen since we first landed in New York. I would pick up the phone and immediately hand it over to my father, or send it to voicemail.

The day before we left Bangladesh, my mother had an accident. One instant her hands were moving lightning quick, chopping vegetables for our evening meal, and the next they were covered in blood. I don’t remember a scream. I only remember being eleven years old and feeling so small as I rushed over to her. She was looking at her hands like they had been severed from her body.

“I cut myself,” she said. Then she started laughing.

It frightened me, the whole thing. I rinsed her hands with a bowl of water and told her to keep still. I heard footsteps on the stairs outside, and called out. She was still laughing when my father burst into the room.

“Pagol! Tumi pagol!” he said to her, tugging her up onto her feet. He instructed me to get a towel as he helped her put on her orna and her shoes. I tried to follow them out the door but my father sent me back inside. I took out the only knife in the house and resumed cutting vegetables.

When they returned, my mother had stitches and her eyes were blank. She was no longer laughing.

“I didn’t feel anything. You were leaving, so I couldn’t,” she told me in one of our phone calls years later.

At a certain point, I could no longer ignore the death count. On the school computers, I scrolled past the graphic images of bodies covered by rubble and the calls for protest. I had spent all my time thinking that this was happening to other people, so I wouldn’t feel anything. Then I overheard one of the voicemail messages.

“She’s in the hospital. She hasn’t woken up,” my aunt shouted over the crackle of the telephone line, “Alhamdulillah.”

I ran my hands over the quilt until I reached the corner where my mother’s embroidery abruptly ended. There, piercing the edge of the fabric was a thin silver needle, still threaded and ready for use. I reached for it, then yanked my hand away. I stared as a small bead of blood rose on my thumb where the needle had pricked it. I began to giggle. I do not have my mother’s hands.

When my father came home and heard the message, he went into his room by himself and, despite his attempts to muffle it, I heard him sobbing through the thin walls. I wasn’t sure whether he was happy to hear that she was alive, or sad that she had not been given peace. I put my ear up against the door and listened for a moment to the sound of his breathing. I could hear him whispering “pagol, pagol, pagol” over and over again like a hymn.

From the entryway, my mother’s photograph stared at us both, waiting for her turn to speak.

is a Bengali-American writer and social activist based in New York City. Her current major project is a novel on intergenerational trauma and Bengali and Bengali-American women affected by violence during the Bangladesh Independence War. She is also the founder of As[I]Am, an online magazine focused on Asian American arts and social justice work. Read more of her work and get in touch at her blog, The Cowation.

Wah-Ming Chang

Sarker Protick’s Of Rivers and Lost Lands

First Lives

There are some, I am told, who never see the dead, though I am as yet unable to believe it. We go to sleep with them as with a mother or a father, for familiar embrace, and when we part, we readjust towards morning. Myself, I admit that in my first days roaming this river with my camera, I was no more attuned to them than the blind is to a mirror, yet over the course of a year I’ve come to absorb, like a mirror, without thought or comment, the weight of the river’s departed.

Often they come to me at night, and fit themselves against me as I sleep. I wake in the pose of prayer so as not to startle them. “Please move your arm,” I may say, and I lift my arm to show them how, and likewise they follow suit. “Please breathe,” I may say, and they watch like children as my chest rises and falls. This, they see, is what defines me, life measured in deep, contained breaths. My camera does not disturb our ritual; in fact, every click of the shutter seems to encourage a new, vigorous motion, and to attract ever more of their number.

Later, when they die once more and then are sent my way again, they remind me, with a syncopated laugh, of the previous time we’d encountered each other, on this same river, along this same path, before this same camera. Their first lives—and their second, their third, and so on—require firm guidance. To deny the dead, I repeat daily, is to deny life itself. What’s left in the world for me, then, is my ghost story. I have never been frightened by this sort of story. Perhaps this means I am the right person to document it. Just as the dead do not seek out their own shadows, I do not seek out mine, for mine will never tell me more than what I already know, which is total and unalterable.

My profession, therefore, lies in the curvature of my gaze, and these portraits are the undiluted reflection. There are those who are allowed to savor life, and when they die again and again, and then show up with a gift at my door, it is like a sun, a bursting star, delivered whole to me.

has received grants for fiction from the New York Foundation for the Arts, the Urban Artist Initiative, the Bronx Writers’ Center, and the Saltonstall Foundation for the Arts. Her fiction has been nominated for a Pushcart Prize, and has appeared in Mississippi Review, Arts & Letters Journal of Contemporary Culture, Kartika Review, and Swarm Quarterly; her nonfiction in Words without Borders and Open City, an online magazine published by the Asian American Writers’ Workshop; and her photography in Open City, Drunken Boat, and the New York Times. She is the managing editor of Melville House.

Sunil Yapa

Rasel Chowdhury’s Desperate Urbanization

“Look at you!” my wife says to me, laughing, when I get home, “such a handsome light-skinned man. Look at the lovely color of your skin!” But she is laughing because she knows it is only the mud which covers my hands and arms that makes them white, the brick mud that dries a pale pinkish red in the cracks of my swollen fingers. And when she sees my face, she stops laughing.

We go together, then, to the bathing spot on the river. She carries soap and a strong cloth and a towel. These are her tools for cleaning me. If I have had a goodluck day, then I am home early, and as we walk to the river there is still light in the sky and our neighbors see us and shout “Hello, are you rich yet?” And we laugh and wave and shout back, “Yes, we are going to buy your house tomorrow!”

Two thousand bricks I make on a goodluck day, forming and shaping the red earth with my shovel, slapping it flat with my wet hands to lay in the sun and I can tell from the way she carries the soap, from the way she tucks the towel under her arm and glances shyly at me as if seeing me for the first time, that on goodluck days my wife feels proud to be my wife.

I work in the brickyard, my neighbor works at the dock. I come home covered in mud, he comes home black with oil. He is a mechanic on the big boats there and he says he has met men from all over the world. From China and Australia and Dubai. He told me that he once met a man from Norway with pale gray lips and breath like a fish, but I didn’t believe him.

Anyway, if he is such a big man, why does he live here beside me?

He likes to tell me I should not swim in the river, my neighbor. He says the river is poisoned. But how could our river be poisoned? I ask him. The city is poisoned, I say, but here along the river, life is clean. Look around you. The wind moves through the grass and the river carries the people from place to place. Life moves as it was meant to move. Look at the crows. Look at the pigeons. Look at the smoke bubbling from the brickyard stack like soap curds in water. He shakes his head at me, thinking I am a stupid man. I shake mine at him, thinking the same.

Today my wife doesn’t talk as we walk to the river. Even on a good luck day I am very tired when I come home and on days like this we go quietly, my wife swaying beside me, the towel and soap under her arm. When we arrive she helps me over the rocks. Some days my arms are so tired that I would not be able to sit without her help. But today I am ok, and slowly we lower my body to the water at the river’s edge. Then she scrubs and splashes, rubbing my back and arms and chest with the rough towel, and after a few minutes the water is dark and shining as though stained with blood and my skin is becoming dark and clean. Now I am feeling better and I ask her if she will sing and although she continues to scrub, working roughly at my neck, I know that she is smiling.

On Sundays if I am not going to the village to take my mother food and clothes, then we again go to the river—our verandah, my wife says in English—and I will pretend to be fixing the handle of my small shovel, pulling a splinter or smoothing a rough patch but what I am really doing is listening to her voice. At home, she refuses out of shyness; but when we are at the river and the boats are passing and the neighbors are calling, then she will sing and I sit on the crumbling bank and listen and say to myself I am a lucky man.

And after all, on a badluck day, when I have hurt myself, or made only half the bricks, or when the boss has told me I am worse than a lazy dog and he will soon fire me—on these days I am not quiet. On these days I talk and talk and talk. I wave my hands and curse the man that caused me to stumble. I curse the man who owns the brickyard. I curse my father for so stupidly borrowing the money that I work to pay off, curse him for dying and leaving us this debt.

But I don’t really mean it. I am only talking to talk. I am only shouting to shout, to hear my own voice rising in defiance, saying the words I wish I could say, but never do.

So I understand my wife’s shyness. But I love to hear her voice, the familiar lilting melody. I love to hear the splashing of the cloth. The slow murmur of the water against my skin. How could our river be poisoned? Look here at my feet, at my hands and my arms which do the work. Look at our river, the rainbow sheen that gathers around us as night falls and my wife hums and scrubs. I am a lucky man to have a wife who sings. I am a lucky man to have a river so dark and clean.

is a 2010 graduate of the Hunter College MFA program in New York City. While at Hunter, he was selected for two Hertog Fellowships as well as the Alumni Scholarship awarded to one fiction student every three years. He has received scholarships to The Bread Loaf Writers’ Conference, The New York State Summer Writer’s Institute, and The Norman Mailer Writers’ Center in Provincetown, as well as the 2012 inaugural Elaine M. Hirsch residency in Sifnos, Greece. His work has appeared in Hyphen Magazine, The Tottenville Review, The Multicultural Review, and Pindeldyboz: Stories that Defy Classification. His story, “Pilgrims,” won The Best Asian American Short Story in 2010. He is currently doing final revisions on a novel set during one day of anti-corporate protests in Seattle, November 1999, tentatively titled, Your Heart is a Muscle the Size of a Fist.

Meera Nair

Shamsul Alam Helal’s Love Story

Doha

My friend Bijoy said he wanted to go back and get the bolt cutter that he had forgotten. Then he waited a beat, as if he was hoping in that space between the words leaving his mouth and his stepping back onto the ledge, the supervisor would say never mind, it’s too dangerous, it’s a safety violation, let’s break for lunch, but instead the man gave a slow grinning nod as if he couldn’t wait for the entertainment to begin. We were standing 400 feet above the ground, on one end of a walkway, a thin bridge of metal and glass hanging off the cliff of the building. The Tornado Towers they called it in Qatar. To us it was just another sky scraper in the desert, just another mountain of glass, another 17 months of work until they gave us back our passports and let us go home for a visit.

Bijoy turned around and stepped back on to the narrow ledge, his hands braced up against the empty space in front of him like a man in a dark room. I felt the building sway in the wind, the railing I pressed up against, burning my back. He took baby steps, walking sideways. Bent his knees and slid his right leg forward first, then jerked his left leg quickly in, his blue uniform shirt billowing against his back like wings. He didn’t look down. It took him sixteen steps to get across.

I counted.

Once in the monsoons, during the hungry season, the circus came to Mombipura. Every day for six days, a man walked on a tightrope tied high above the ground and he had the same bent knees, the same preoccupied look, as if an important idea had just occured to him. I wondered if Bijoy thought of it right then too. I remember Bijoy whispering: He must have put glue on his toes to make the rope stick.

We were 10 years old and sceptical about everything.

Up here you look down and your heart stops. There is nothing but hard white sky beside you and around you. Once in a while a hawk flies past and you look up and see the bird’s white breast, hear the slow flap of its wings as it climbs into the sky and for an instant you toowant to spread your arms out and step into the shimmering air.

Up here there’s no Doha, no stinking dormitory, no airport that trapped you. From 52 stories up, the city is veiled and mysterious, a faint, harmless circle in the sand far below.

The Qataris never look up. They don’t see us as they glide past in their Jaguars. We all look the same in our uniforms. Blue shirts. Orange hard hat. On the building sites, no one can tell we are from Mombipura, or that for a whole month when I was sixteen, I loved the same tall, curly-haired girl Bijoy did.

Bijoy came back across the ledge on his hands and knees, pushing the damn bolt cutter in front of him. It was heavy, it could have tipped him over the side. The supervisor giggled, “Look at him, such a baby!” and turned around to see if we agreed with him. But we wouldn’t give him the satisfaction. All I could concentrate on was the scrape of iron on steel and my heart jackhammering in my chest. Then it was over and I put my hand out and hauled Bijoy to his feet and he gave the tool to the supervisor who was grinning still, the same smile he plastered on as he refused to let us stop for a drink of water

Bijoy was fine in the hydraulic lift going down, but when we stepped off he got the shakes and I had to grip his elbow to keep him from falling. It was like the time he got malaria when we first got to Qatar – as if the shivering was in his bones.

They can take your job away, deport you, put you on a plane the same day, for the smallest mistake. Bijoy had his house half-built in the village, the roof not yet in and the monsoons coming on. He must have thought it was worth it, going back for the bolt cutter. We didn’t talk about it.

He died that night.

Heart attack the doctor said. Who dies of a heart attack at twenty-five? In Qatar they do. All the time. Bishen. Jobi. Georgekutty. Three guys I sort of knew in my unit are gone. In the newspaper from back home they say its the airconditioned nights following the blazing days that mess you up. I think Bijoy just wanted everything to stop.

They sent him home in a plywood coffin. I had to call his Ma. I thought of her, wiping her hands on her pallu before picking up the phone. She wasn’t used to it, that Samsung he bought her; he would laugh, imitate how she held the phone gingerly, a careful distance from her ear as if at any moment it would spew something cold and nasty at her.

I said Bijoy into the phone. That was all I could say. Bijoy.

I went down to the bazar to Lovely Photo studio the morning after they sent him back. It was my day off. I wore his red shirt. His shoes.

Alone in that tiny room, in the pauses between the camera’s clicking, I could hear my heart, beating and beating still.

is the author of the story collection Video (Pantheon), which won the Asian American Literary Award and was a Washington Post Best Book of the Year, and a middle-grade children’s book Maya Saves the Day (Duckbill, India). Her stories and essays have appeared in the New York Times, National Public Radio’s Selected Shorts, the Threepenny Review, Calyx, National Post and in the anthologies Delhi Noir (Akashic Books), Charlie Chan is Dead-2 (Penguin), and Money Changes Everything (DoubleDay). Nair is the recipient of a MacDowell Fellowship and has twice won fellowships from the New York Foundation for the Arts. She is currently the Writer in Residence at Fordham University. Her current project, a novel titled Harvest, is a love story set in southern India against the background of the communist takeover in the 1950s.

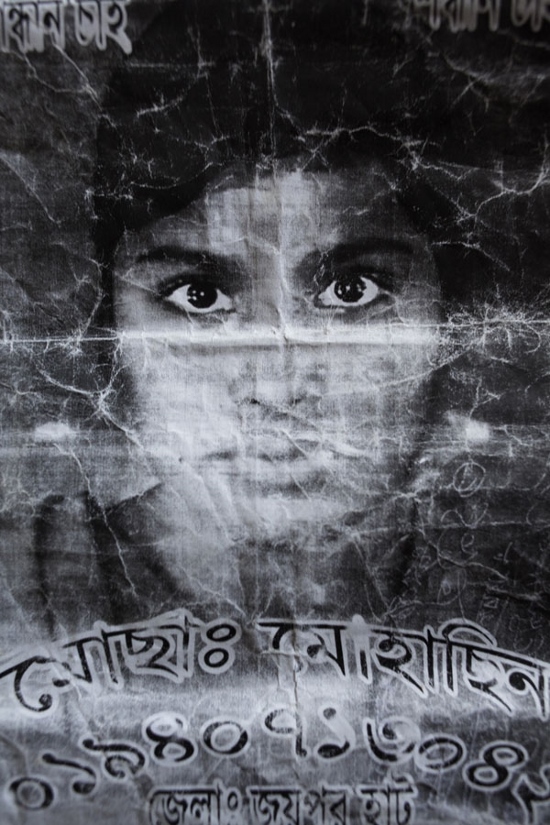

Faheem Haider

Shumon Ahmed’s What I have forgotten could fill an ocean, what is not real never lived

Thirteen Ways of

I recoil from the biographic. I recoil from the sentimental. I recoil staccato, like a shotgun shout I’ve long kept ball-gagged down my gullet, chained to an untravelled passage that runs right parallel my heart and around my lungs, and stops at the top reaches of my diaphragm, when I see penance in work.

Yes, though I’d like it to be not, this is nonsense. Every propositional account of anything at all is always confessional, and so, biographical. Whether you think so or not, all art is propositional, the material as much as the conceptual, mechanical, digital.

Art as Propositions! If that, I can’t help it. Art as Penance. I recoil from the sight, YES, but I can’t look away: I’m in the pileup.

Shumon Ahmed’s photographs stung my skin like screen print-shrapnel crackling up from a mechanical documentation machine. I saw the pictures online, as you might have done when you read the Times, like yesterday: that’s too far away from me-there’s no one there. I’m looking at these photos long-distance. Like I do and I’ll do about most of what’s happened in Bangladesh, from here in the relative comfort of my home in New York.

Shumon’s work is a city of missed connections and blazing turns away.

Shumon is my cousin’s name. His mother died–she killed herself –when he was 6 years old; a small woman, large in heart, she couldn’t get her mind under control and fell through the schizophrenic cracks in the pictures the world insisted she install and hang. Shumon: the calm mind, the calmed mind; the peaceful mind, to put back the pieces of a shattered “I” into a workable gestalt. My cousin’s now 45 years old. My cousin’s a good man. He came to visit and sat at Amma’s bedside when she died 9 years ago.

My cousin, another one, an Ahmed, 18 years older than me called himself an Armhead. He was a Brit, not born there, though entirely raised in the place I call Britland. The Angles have very little to do with England now. “Borrowed Time on Disappearing Land”. The EDL claimed ownership of Fred Perry and all the best chippies in the country. Great legislators, old and mustachioed, represent(ed) the East End. And the East End is Olympic.

I haven’t been back to Bangladesh since 1997, when I was 18 years old, though I have seen that documentary about Louis Kahn,” My Architect”, at least twice. I am a “Dhaka’iah” from Dhanmondi, more or less born there, more or less raised there until I was 12 or so and then onto the States, New York and Broadway, called so because the way was broad.

I’ve been writing about Bangladesh for some years now, and had no desire whatsoever, until recently, to visit; were I born where I live I’d have been an ABCD-American Born and Confused Des(h)i. My father, Abba, the Dhaka’iah kutti, the economist, scholar, cricket player, the whisky swigging industrialist, and, recently, the upstate New York hotel night auditor, went back alone to Dhaka some weeks ago and then things nearly became so that he wouldn’t come back home.

March 17th was the celebrated birthday of the celebrated birther of the Bangali Nation, Bongobondu. It was also the day that at his sister’s home in Dhanmondi, Abba suffered a heart attack in silence for over an hour between the hours of 3 and 4 am, and after spilling his secret, he lost consciousness, stopped breathing and fell into himself. Were it not for that holiday, and that traffic in Dhaka was passable only on that day, Abba would have died in phuphi’s jeep. My phupi is the one aunt with whom I have had the most ambivalent nephew-aunt relationship—I remember she had only the most distant things to say about my dead mother. She saved Abba’s life, even though he died.

Abba was revived, after flatlining, his heart: a rock. I owe my father’s continuing life to a set of woven conflicts that now envelop me: My family ties that now bind me in circumstances of nephelial obligation, and the unmolested history of Bangladeshi nationalism that sees fits to accord nationhood within its borders only to itself, saved my father.

“Ami ki eye deshey morbo (Am I to die in this country)?” And not in another, my home? My father said in his bedroom, I heard, as he was felled by his heart and spent an hour quietly crawling on his stomach to get to the adjoining bathroom for a drink of unpotable water that he couldn’t get to, inch crawling to save others the misery of awakening.

There’s a picture, my baby sister sent me from Dhaka after she and my older sister caught the first flight out there. She’s in a salwar kameez, tired and calm, and is pushing Abba sat in a wheel chair and he’s smiling agog, two thumbs up. You see, less than 5% of those who suffer cardiac arrest in the United States survive the event, and a large share of those people don’t make it past the first few days. There’s luck, call it. Or contingency, or the fact of a holiday where people destroyed by the blunderbuss of nationalist politics choose to stay at home and breath a bit deeper, and speeding jeeps outfitted with dying men make it to a hospital quicker and in time to get a Code Blue from doctors when their hearts shut down.

I’ll take a thumbs up when I can get it, even if from the Imperial Stands, just so that I might have another moment to do my penance.

is an artist, art critic, and a writer . His work tracks his relationship with the 13-year-old “War on Terror,” aka WoT, and the larger 100-year old family of Wars into which WoT was adopted without notarized papers.