Climate change and development threaten the indigenous fisherfolk communities of Mumbai

March 30, 2023

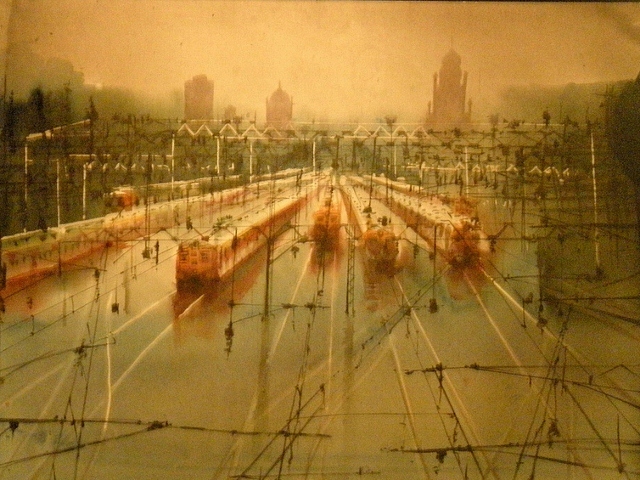

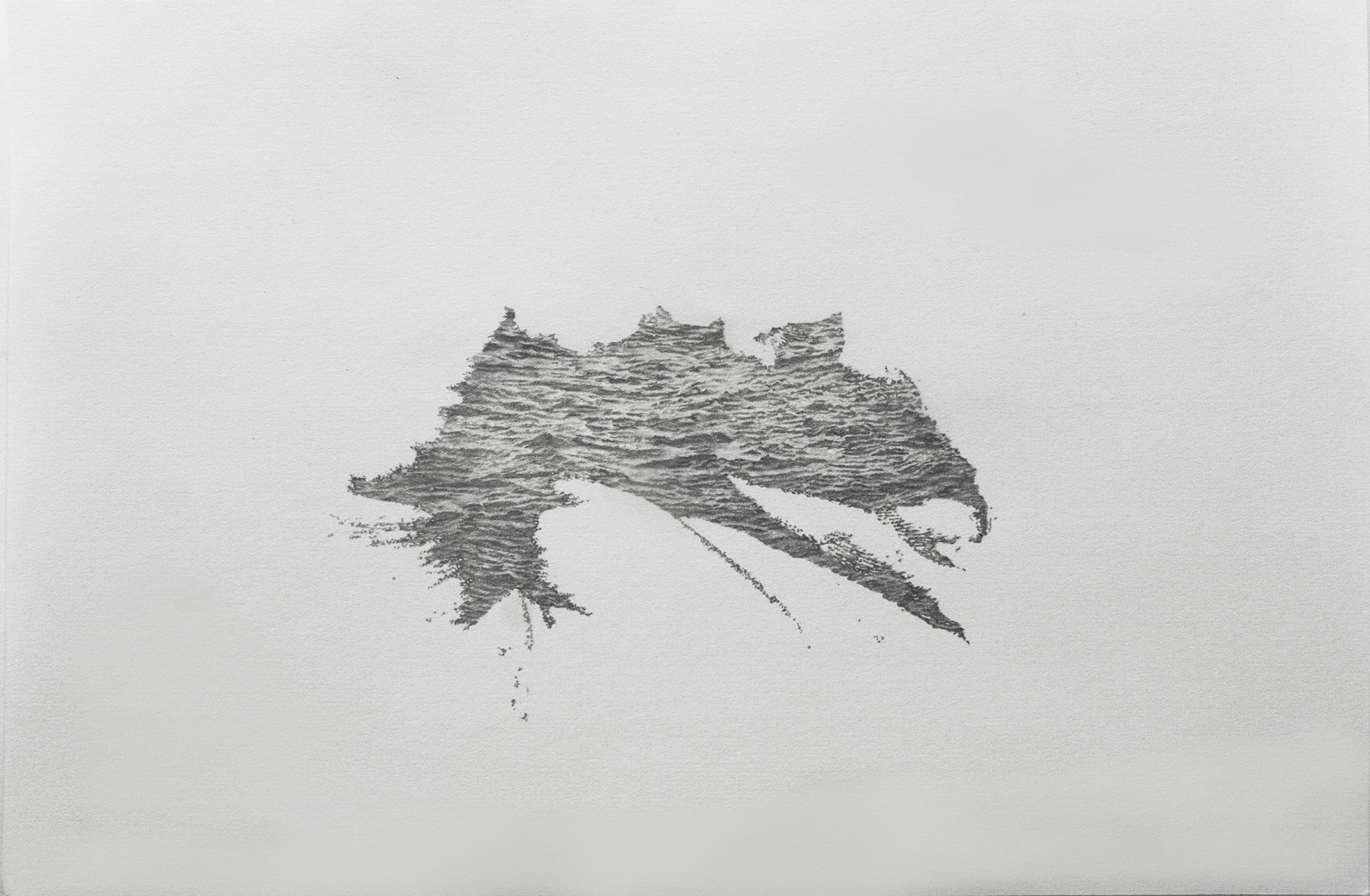

This piece is part of the Climate notebook, which features art by Katrina Bello.

Mumbai is sinking! read a headline in the Times of India last July, when the bustling city on the western coast of India was in the midst of its wet season, heavy rain lashing against its slums and skyscrapers day and night. It was an amusing proclamation to make to Mumbai’s twenty million inhabitants who have already been cautioned against its imminent fate many times. The cry felt more like a doomsday conspiracy theory rather than the fact that in the last decade, India’s financial capital has become one of the most vulnerable to climate change. Slowly but surely, Mumbai is sinking.

If, or when, Mumbai is all but swallowed by the sea, history might tell us it has been returned to its original condition. The British spent two hundred years creating Mumbai into a continuous peninsula—before it became a city, it was an archipelago of seven small islands that stood independently in the Arabian Sea. In the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, the islands underwent a series of land reclamations, where marshes, mangroves, and mudflats were slowly replaced with embankments, leveled hills, and rubble.

Today, the conjoined islands are buzzing localities with just their namesakes: the central business district of Worli, the fishing wharf of Mazagaon, the upscale downtown area of Colaba, or Kolbhat. In the sum of its parts, Mumbai has accommodated tens of millions of migrants who flock from every corner of the country for opportunities in the magnet for industry and labor. At the same time, Mumbai’s elite, some of the richest people in the world, who trade in stocks and commodities or make big-budget films, harbor lofty ambitions for Bombay, as they like to call it, to one day join the ranks of New York, London, and Paris.

Still, a walk along Mumbai’s coast is like peeling back the layers of an outward-looking city. Its original inhabitants for over five hundred years—the indigenous fisherfolk communities also known as the Kolis—are still here. They live in koliwadas, homes that open on to the sea and are clustered in fishing settlements. The Kolis, whose population is an estimated five hundred thousand people, actually gave the city many of its names—even the name Mumbai is believed to have derived from Mumbadevi, the sea goddess and patron deity of the fisherfolk. The Kolis are at the heart of Mumbai’s fishing trade—the men, responsible for the catch, take their boats out to sea, while the women set themselves up in sprawling courtyards to sell the catch of the day on big blocks of ice. Every year, the community pays homage to its culture with an annual seafood festival on the marshy banks of suburban Versova.

The Kolis don’t need to read alarming headlines to know that Mumbai is sinking, either. Over the years, more cyclones have hit Mumbai’s coast with increasing intensity, and the combined threat of rising sea levels, pollution, and extreme heat have taken a toll on their traditional occupation of fishing. In the last decade, their fishing villages have witnessed erosion of up to eighteen meters, while fish commerce has slowly declined due to overfishing and depleting fish stocks. Climate change may stretch the whole city’s fortitude to its limits, but its impact is most visible here, among the indigenous fishing community.

In the Versova koliwada settlement, which runs along the Malad Creek and spits out into the Arabian sea, the Koli community is one of the richest fisherfolk communities in the city. The Kolis live as a co-operative: three thousand people own fishing businesses, and they employ a further five thousand people. The fishermen catch more than twenty varieties of fish and crabs, which are sold at the auctioneers’ market and the bazaar.

Manohar Kalke, a third-generation Koli fisherman from the Versova koliwada settlement, first caught a fish when he was seven. He accompanied his father on their fishing boat, traveling about six miles away from shore. He watched how his father cast each of the seven fishing nets, fastened to metal hooks on the boat’s edge, so wide into the sea that it seemed like no surface area was left untouched. Then, the father and son sat on the briny waters for hours and waited. “That day, we caught buckets of fish,” he recalled with a smile on his face. “This is what my father taught me because it was what his father taught him.”

But Kalke, who is now fifty-six years old and decades into managing his family’s fishing business, doesn’t plan to pass on the family tradition to his children. “What is there to pass on?” he sighs with resignation. Kalke is tall and muscular with a long mustache that matches his curly, jet-black hair. He’s dressed in a sports jersey and shorts—a modern-day fisherman—and has been working on the banks of Versova since the morning. “This business is fast-dwindling,” he explains while eyeing his workers, who stumble out of fishing boats and begin separating the catch from the nets.

There are many market reasons for the dwindling business: increasing fuel prices that make buying diesel fuel for boats unaffordable, competition from big trawlers and international conglomerates, and changing demands for fish consumption. But the weather, which Kalke claims to know like the back of his hand, has not been an ally lately either. Extreme heat marked this past summer, which led to fish vanishing from the waters. “Our catch has shrunk so much,” says Kalke. “Before, even if we caught less fish, we could make a living with what we were paid for it. But now, everything is so expensive.”

Frequent cyclones have also severely affected the fishing business. Cyclone Ockhi, which was one of the worst to hit India’s west coast in 2017, was rivaled by Cyclone Tauktae in 2021, which destroyed many of the fishermen’s boats in its wake in an already fragile, pandemic-hit fishing economy. As a result, in the last ten years Koli fisher boats have decreased dramatically in numbers—from five thousand to just five hundred, says Kalke. Some of the fishermen sold their boats and land, took the money, and moved into urban labor occupations.

Kalki points to a colorful boat by the shore behind him. “That boat’s been standing here for the last seven days because of the storms in the last few days,” he says. “It will finally sail out today.”

The extreme heat, the vanishing fish, and the increasing cyclones are not disconnected—in fact, the latter two are the direct consequence of the former. According to the World Economic Forum, India’s coastal water temperatures rose by half a degree over the last decade, which has had a devastating knock-on effect on the fishermen. A report by India’s Ministry of Earth Sciences further found that between 1951 and 2015, the surface temperature of the Indian Ocean increased by 1 degree Celsius, or 33.8 degrees Fahrenheit in the equatorial region at a rate of 0.15 degrees Celsius per decade. As a result, cyclones along the western coast have become more frequent and more severe, along with a rise in marine heat waves. The increase in water temperature destroys the coral, which means the fish either die or migrate to cooler waters and new habitats. This also directly impacts the fish’s ability to reproduce and eat because the heat kills phytoplankton, or fish food. Consequently, the years of low catches have brought down the morale of many fishermen. “The sea has changed,” says Kalke. “It no longer feels like ours.”

But when Kalke thinks about the term climate change he thinks of the weather, not the long-term shifts in temperatures and weather patterns that are fundamentally changing the earth. For him, the immediate threats to the Koli way of life come from overfishing by large, merchandized bull trawlers that drag their nets across the sea bed, which the Fisheries Department allowed in the late 2000s. “Once they began to fish in our waters, they completely threw us Kolis under the bus,” he says, angrily.

The trawlers can capture hundreds of pounds of fish in one go, which are then sold in large fishing markets operated by commercial companies. Officially, these numbers are captured in the 2020 report by the Indian government’s fisheries department, which found that the number of fish caught had increased in the past ten years from 3.2 million tons in 2010 to 3.7 million tons in 2020. But this also occurred alongside a decline of 9 percent in overall fish catch across the country, according to the government-run Central Marine Fisheries Research Institute. In Maharashtra, Mumbai’s home state, fish catch in 2018 dropped to its lowest in forty-five years. Other parts of India have been affected, too. During the fishing season in 2019, 80 percent of fishermen in the western state of Gujarat packed up their boats two months earlier than usual because there wasn’t enough fish to catch.

Kalke believes that urban development will ultimately lead to Mumbai’s demise. “The government wants the Kolis to leave so it can develop the city into Singapore,” he says. “But our island was thriving before they put down roads and bridges and dragged us into Mumbai city.”

Still, Mumbai is known as the city of dreams, and it must carry onwards to create space and meet the demands of its overgrowing population. Ambitious infrastructure projects have begun along the coast, including a statue of the Maratha warrior king Shivaji, and a controversial twenty-mile-long coastal road, which is reclaiming vast portions of the sea. The Kolis have opposed such projects vociferously. They argue the coastal project not only swallows the shallow seas that coastal fish workers depend on, but it also alters tide patterns that govern the behavior of fish.

Last August, Maharashtra’s government launched the Mumbai Climate Action Plan website, which was touted as the first initiative of its kind in urban India and South Asia. “Climate change has come to our doorstep,” said the municipal commissioner at the launch, noting that most of July’s rainfall occurred in just four days, and that cyclones in the region were increasing. He warned that the city’s business and government hub, located at the southern tip of the city, could be “underwater” by 2050.

The Climate Action Plan aims to increase the resilience of communities like the Kolis by introducing sector-specific strategies for “mitigation and adaptation,” according to the official website, by way of asking residents to implement local action plans, finding housing and infrastructure solutions, and protecting natural resources like mangroves, which are the coastal forests situated between the ocean and the land, and natural urban drainage systems.

In drafting these strategies, the government needs to include members of the fishing community. The Kolis have a relationship with the mangroves, which grow in saline or brackish water and have a complex root system that can dissipate the harsh sea waves from tsunamis, storm surges, and soil erosion. They look after it and help it grow, and in return, it teems with a variety of fish and marine fauna to provide for their livelihoods. But the coastal fishing villages and the mangroves are often the first to be sacrificed for real estate when the city demands more space, despite the city recognizing that its coastal ecosystem depends on them.

And yet, history never forgets. The Tandel Fund of Archives, an archival project run by artists Parag Tandel and the Kadambari Koli community, has hallmarked the many years of displacement of the Koli community of Mumbai. In the archive, one poem titled “ईरपाल (erpal),” or grievance, by the local Koli poet Shahir Pundalik Mhatre, bears witness to the displacement. He writes in the poem’s opening lines: “We have lost everything. Who has reaped? still, we are displaced in our freedoms.”