Suppressed sexual violence in the name of revolution lay in the abyss of our consciousness.

October 25, 2017

The Cultural Revolution was intended as a decisive break with China’s past, in order to start the future with a clean slate. In this excerpt from Bei Dao’s absorbing memoir City Gate, Open Up, a small residue of the country’s millennia of literary culture lingers in the form of his father’s book collection — for a short while, at least.

The Cultural Revolution was intended as a decisive break with China’s past, in order to start the future with a clean slate. In this excerpt from Bei Dao’s absorbing memoir City Gate, Open Up, a small residue of the country’s millennia of literary culture lingers in the form of his father’s book collection — for a short while, at least.

from City Gate, Open Up

by Bei Dao, translated by Jeffrey Yang

My father was a literature enthusiast in his spare time. Such hobbies can become the epitome of miscellany—seize whatever you can buy, no picking and choosing. The russet-colored bookshelf in our home, neither too big nor too small, held around three hundred titles; it stood centered against the north wall in the outer room (where Mao Zedong’s portrait hung during the Cultural Revolution, and before that, where we displayed the ancestral tablets for offerings), and still exists to this day; just from looking at this bookshelf one could see the importance of culture in our family life.

We categorized our books according to a strict hierarchy: the works of Marx-Engels-Lenin-Stalin-Mao, along with the collected works of Lu Xun, dwelled in the heights looking down, and represented the established canon; the second tier, representing tradition, included classical texts plus modern dictionaries, such as Three Hundred Tang Poems, Ci Poems of the Song Dynasty, Perfected Admiration of Ancient Prose, Romance of the Three Kingdoms, Water Margin, and Dream of the Red Chamber, as well as the first major dictionary of the twentieth century, Ciyuan: Source of Words, and the Dictionary of Modern Chinese and the Great Russian-Chinese Dictionary; farther down, contemporary revolutionary fiction represented a moral, Confucian orthodoxy, like Steel Meets Fire, Red Cliff, Builders of a New Life, Wildfires and Spring Winds Raging in the Ancient City, Bitter Cauliflower, among other titles, as well as collections of essays, such as Wei Wei’s encomium to soldiers Who Are the Most Beloved People? and Liu Baiyu’s Red Agate. The latter category served as the prime target of my excerpting prowess—those flowery, rhetorical passages embedded into my error-laden compositions littered with wrongly written characters shined with an excessive glare. The lowest rung belonged to the hodgepodge of magazines that represented current cultural tastes, among them Harvest, Shanghai Literature, Study Russian, although the bulk of them focused on the movies, so in addition to Popular Cinema, Shanghai Film Pictorial, and other more popular ones, we subscribed to a pile of specialty periodicals, like Chinese Cinema, Film Literature, Cinematic Arts, Screenplay Magazine, and so on. I’ve often wondered if, all along, my father harbored a secret desire to write a screenplay.

My reading interests turned the hierarchy on its head, inverting the bottom and top. I started with film magazines, particularly the ones on screenplays (which included the working scripts directors used), probably because the writing was easy to understand, relying mainly on dialogue, tight plots, strong and vivid images—a transitional stage between the little picture books and real books. Although such readings did come with a load of specialized terminology: stop-motion, flashback, fadeout, long take, voice-over, push pull rotate pan, etcetera; and yet, this issue proved to be no hindrance, like being able to sing without knowing anything about the musical staff. For me, reading a screenplay was more or less equal to watching a movie for free, and in fact, felt even more gripping—words created visual scenes with a much wider space for the imagination to roam. The relevance of this became wholly apparent when I started to write poems. I considered Eisenstein’s use of montage and, rather than expounding on it as a theory of film, adopted it as a theory of poetry.

Rising up a level, I gradually became obsessed with revolutionary fiction. What aroused my heart most about these books were the descriptions of sex. And admittedly, Feng Deying became my foremost instructor on sexual enlightenment, his long novels Bitter Cauliflower and Winter Jasmine among the earliest sexually explicit reading material available; they involved brutal violence as well as perversions of the pornographic incestuous variety. Coming upon these passages, my heart leaped and flesh trembled with fear; I wanted to stop but couldn’t bring myself to, and due to my issues with my own class status, intense feelings of guilt followed. I’m convinced that these books had an enormous influence on the sexual awakening of our generation: suppressed sexual violence in the name of revolution lay in the abyss of our consciousness.

Reading books brought much praise from adults. At a tender young age, where could one go to gain such approval? I recall I was in third or fourth grade when my mother brought me to the Library of the People’s Bank of China; from a shelf, I chose a thick Soviet novel, more than seven hundred pages long, and sat down in the reading room, pretending to read with great pride. A librarian made a loud fuss over nothing, attracting other patrons who circled around and stared at me, as if I were a space alien. And indeed I felt like a space alien, reading a celestial script, bracing myself in the presence of so many new words, leaping forward and backward, unable to string together any hint of a plot.

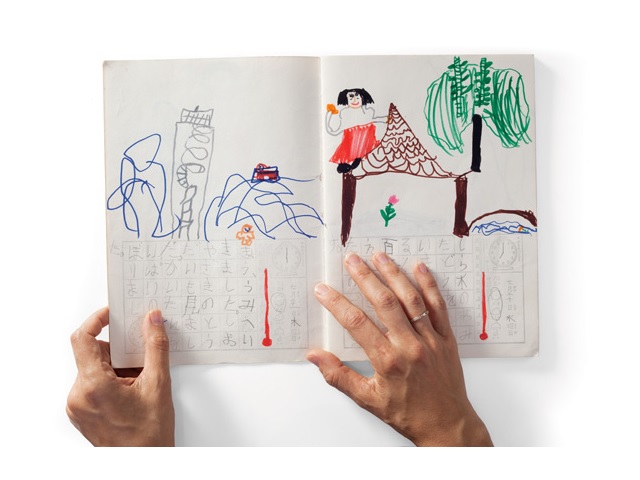

I scaled up to the ancient classics, owing in large part to my father’s willpower—he forced me to recite classical poems from the Tang and Song, typically over the winter and summer breaks, one poem per day. At an age when children only want to have fun and play, where could one find the carefree, idle mood of the ancients? The curtains swayed as I rocked my head back and forth, chanting a poem: “Moss green on the steps / grass sheen through the screen / Harmonize with the plain-plucked qin / read the golddust sutras / Chats and laughs with goose-winged scholars / who come and go, no empty-headed idiots among them / No din of other winds and strings to irritate the ears / no official records to toil over / Zhuge’s hut in Southern Sun / Ziyun’s pavilion in Western Shu / As Kongzi once said: ‘How could such a room be humble?’”* Concerning those books on the top shelf, everything from their stately grandeur to their thick spines made people wince; it wasn’t until the Cultural Revolution that we consulted them for writing big-character posters. Reading and reading page after page I finally understood why Father placed those books at the summit—it’s so lonely and cold at the top.

*

Around the age of ten I discovered a momentous secret: large stacks of banned books stashed away in the attic space above the corridor between the front door and the kitchen.

The boy was short, the attic high; this proved to be no obstacle as curiosity worked its mischief and, alone at home, I positioned a tall stool on top of two chairs, each balanced on the other. This required an extraordinary degree of precision for all the furniture to fit flawlessly together. It was, essentially, an acrobatic performance without, sadly, any audience present; or it could be said that I played the sole audience member, determined to climb up and see what could be found.

I opened the attic hatch; the smell of dust and old papers blasted me in the face. I often browsed used bookshops where the odor of old paper—refined, remote—smelled like incense, summoning souls from faraway places. But here, maybe from being shut in the dark for so long, the odor emanating from the books smelled a hundredfold stronger; I felt like a prisoner, brimming with hostile aggression, the fumes making me dizzy. Regaining my focus, I held my breath, steadily adapted to the pungent onslaught as well as the dim surroundings, and with swift intuition, it dawned on me that I had found a real treasure trove.

To this day I can still remember the condition of a number of those books, the degree of damage to certain bindings, as well as that very unique odor. They had come from a range of different epochs and regions, each following a different route on its journey. Consider the source of the paper pulp for one—cotton and rice straw mashed together, then add in the differences of temperature and humidity in various locales, the absorption of each season’s fragrances and nourishing flavors. Each book possessed its own life, possessed its own age, birthplace, and name.

My family’s attic library could be divided into four rough categories: first, old editions of Strange Tales of the Tang and Song, Feng Menglong’s Stories to Caution the World (unabridged edition), Investiture of the Gods, and other classic fiction titles of this sort; second, novels published before liberation by authors such as Zhang Henshui, Yu Dafu, among others, who with Mao Dun had been banished to the cold palace, having fallen out of favor largely for their explicitly erotic descriptions; third, assorted fashionable magazines from the 1930s and 1940s, including The Young Companion, Women’s Pictorial, Movie Art Pictorial; fourth, specialized textbooks my mother used during her medical studies, like Physiology and Anatomy and Comprehensive Gynecology.

As is evidently clear, my family lived a cultural double life: The public bookshelf, out in the open for everyone to see, embodied the status quo and mainstream culture; the attic stacks, hidden and sealed off, embodied the illicit and taboo. From that day on, after discovering the secret in the attic, I, too, was thrown into a double life.

Coming home after school, I piled up the chairs and stool, scaled to the heights, popped open the attic hatch, groped my way through the dark, and extracted one title after another, first making a preliminary assessment before transporting them below. After finishing my reading, I’d put everything carefully back before my parents returned home from work.

The attic was deep, my arms short; I wanted to reach into the abyss and so added one more little stool to climb onto. And then with the slightest of slips, rider thrown horse felled, I crashed to the ground, bloodying my nose and bruising my face. Of my early reading experiences, besides the relationship between the public and the hidden, aches and pains unfailingly established their contrary significance. I think this must have been the necessary price to pay for reading banned books.

From the strange tales of ancient times to the novels of the modernist era, depictions of sex were much more depraved and fantastic in those books than in revolutionary fiction, some- thing that actually made sense to me as many sexual taboos had formed fairly recently. Physiology and Anatomy and the other medical books that described the structure and function of female anatomy really made my eyes spring out and my mouth gape open with wonder: The mysteries of birth revealed! And compared with those brilliant May Fourth sanwen (“scattered writings”) prose stylists, a writer like Liu Baiyu simply couldn’t touch them; he was a quack selling fake herbs and nothing more.

The disarray in the attic aroused my father’s suspicions; he installed a lock on the hatch, and yet even this couldn’t dampen the deep resolve inside me. I scoured east and rummaged west, until at last I found the key.

*

My secret attic-reading started at age ten and continued until age seventeen, when the Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution exploded. For a time, I would still steal the attic’s forbidden fruit while actively participating in the rebellion. Then that Sunday in August arrived when the Red Guards posted the announcement on our building, saying there’d be door-to-door searches, setting a deadline to hand over any “four olds” possessions to the neighborhood committee—do not delay or risk being executed under lawful authority.

We busied ourselves for three days. Father opened up the hatch, brought down the whole hidden library, and piled it into one heap. These books, so central to my upbringing, exposed in the full light of the day, now waited to be delivered to the flames. I imagined them in the fire, the shapes and sounds as the pages curled. While saddened, I unexpectedly felt a stealthy thread of delight.

* From Liu Yuxi (772–842), “Inscription for My Humble Room.” Lines 3–4 and 5–6 are not in the correct order in the child’s recitation and are interchanged in the original poem.—Tr.