Nearly 30 years after its birth, reproductive justice remains a fundamental feminist framework addressing issues of bodily autonomy, equity, and liberation.

January 7, 2022

The United States Supreme Court is currently poised to overturn Roe v. Wade, a 1973 ruling that protected the right to abortion for birthing people across the country. Advocates know both that gutting Roe will leave the most marginalized in our communities in peril—a truth recognized by those organizing around a reproductive justice framework in the fight to defend abortion as essential healthcare—and that the ruling’s application had always left out many of the most vulnerable. In order to fully understand what’s at stake and how we arrived here, it’s important to learn about the roots and foundations of this ground-breaking, feminist of color–led movement.

A group of Black women first coined the term “reproductive justice” while organizing to expand the scope of the Clinton administration’s Health Security Act in the summer of 1994. Activists and organizers working within the reproductive health movement birthed this new framework during their time at a conference in Chicago. Rooted in the struggles they had personally encountered or witnessed within their communities, reproductive justice pushed the boundaries of the staid debates about abortion that dominated white feminist spaces and around what healthcare access could mean. Following the conference, the group named themselves the Women of African Descent for Reproductive Justice and organized a series of actions to draw attention to how normative healthcare policies, even those touted as expansive or progressive, continued to deny poor women access to vital reproductive health services, including abortion. Moreover, they began to organize around the vast range of unmet reproductive health needs within communities of color, including HIV/AIDS prevention, maternal mortality reduction, cervical and breast cancer screenings, and wellness planning. Their demands drove home that healthcare, particularly reproductive healthcare, had to be intersectional in order for it to be effective. Soon after, members of this group traveled to the 1994 International Conference on Population and Development, which was being held in Cairo, Egypt. There, they met organizers and activists who spoke to the needs and experiences of women living in the Global South (or the Third World), expanding their own organizational language to include claims based in human rights frameworks.

These foremothers of the Reproductive Justice Movement had been organizing in tandem with a range of women of color groups that had been working throughout the 1980s to expand the conversation around reproductive health to include questions of poverty, race, and gender oppression. (Loretta Ross reminds us that ‘women of color’ is a political designation rooted in solidarities towards racial and economic justice.) Collectively, these groups advanced innovative ways of raising public awareness around critical issues while continuing to center the voices of those most directly affected by these harms. They foregrounded the personal experiences of the individuals within the movement to broaden policy conversations, insisting that meaningful change required a holistic approach to reproduction, justice, and equity. In 1997, many of the groups working towards these goals organized under the umbrella of the SisterSong Collective. The collective, which had many member organizations, worked to build coalitions among groups, across geographies—equipping countless activists to engage in vital movement building. Groups like INCITE! Women of Color Against Violence also highlight reproductive justice as anti-violence strategies beyond state responses to sexual and domestic abuse.

Nearly 30 years after its birth, reproductive justice remains a fundamental and profoundly feminist framework with which to approach lasting and new questions of bodily autonomy, equity, and liberation.

I. Political Foundations & Manifestos

Gathered here are the primary sources and building blocks of the reproductive justice movement. They allow us to understand what the foundational theories of the movement were and how they have been refined, expanded, and pushed forward over time. Each of these documents speaks, in some way, to the importance of considering the lived experiences of those most impacted by reproductive healthcare policies and expanding a collective understanding of what building a more equitable conversation around these issues requires from each of us. Included are the words of Loretta Ross, a founding member of the SisterSong Collective and co-creator of the term “reproductive justice”; a call to action and manifesto placed in national newspapers by the Women of African Descent for Reproductive Justice; an updated call to action and distillation of the many facets of the movement authored by Sujatha Jusudason; and a curated digital exhibition depicting the long history of reproductive justice organizing, its material culture, and its many phases.

- “What Is Reproductive Justice?” by Loretta Ross, SisterSong Women of Color Reproductive Health Collective

- Black Women on Universal Health Care Reform, ad placed by Women of African Descent for Reproductive Justice, 1994

- “A New Vision for Advancing Our Movement for Reproductive Health, Reproductive Rights, and Reproductive Justice” by Sujatha Jesudason and Asian Communities for Reproductive Justice

- Birthing Reproductive Justice: 150 Years of Images and Ideas, curated by Reproductive Justice Exhibit Planning Team at the University of Michigan

II. Imperial Legacies & Historical Foundations

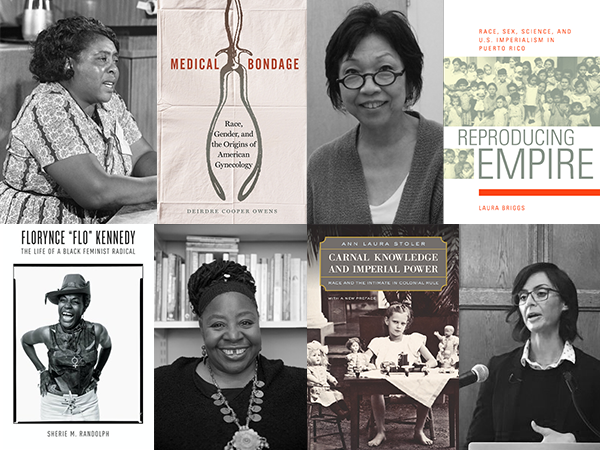

Understanding the complexity of intersectional demands for reproductive justice requires us to grapple with the ways that controlling birthing bodies has functioned as a central plank of slavery, colonialism, and coercion. This list begins with Dierdre Cooper Owens’s study of the roots of modern American gynecology, which delves into the lives and labors of enslaved women who were both examined and experimented on in the name of scientific inquiry while also themselves working as skilled medical practitioners, researchers, and nurses to contribute to the field of gynecological science. Exploring the women’s lived experiences alongside the medical research that they contributed to, Owens shows how racial formation and modern medical science were mutually constitutive of one another. In doing so, this text illuminates not only ways that biomedical inquiry is always situated within complex relations of power, but also the ways that individual women occupied multiple standpoints within the history of American gynecology. The list moves on to consider the work of Laura Briggs and Ann Laura Stoler, both of whom demonstrate the centrality of policy aimed at reproduction and the management of intimate lives to the project of American and European empire, bringing questions of birthing, birth control, infection screening, marriage, and sexual coercion to the fore as central elements of how imperial power was justified, maintained, and prolonged. Evelyn Nakano Glenn, meanwhile, considers the linkages between reproductive labor and care work in the twentieth century. Angela Davis’s pathbreaking text offers an analytic that brings together many of these questions, arguing for the centrality of reproductive rights to antiracism and gender liberation work.

- Dierdre Cooper Owens, Medical Bondage: Race, Gender, and the Origins of American Gynecology

- Laura Briggs, Reproducing Empire: Race, Sex, Science, and U.S. Imperialism in Puerto Rico

- Ann Laura Stoler, Carnal Knowledge and Imperial Power: Race and the Intimate in Colonial Rule

- Evelyn Nakano Glenn, “From Servitude to Service Work: Historical Continuities in the Racial Division of Paid Reproductive Labor,” Signs 18, 1 (Autumn, 1992): 1-43

- Angela Davis, “Racism, Birth Control, and Reproductive Rights,” from Women, Race & Class

III. Biography of Struggle

The stories of how leaders in the struggle for reproductive justice found their way to the movement vary. The following section features interviews, autobiographies, and biographical portraits of women whose lives and activism encapsulate the fundamental demands of the movement. Biographical perspective allows us to see how the themes of access, equity, and intersectionality that reproductive justice movements foreground were central to the lived experiences of the movement’s earliest advocates. The list begins with the autobiography of Shirley Chisholm, a pathbreaking politician and activist whose staunch and early advocacy for the importance of reproductive freedom in poor communities of color preceded the mainstream alignment of many with her demands. It also includes interviews with reproductive justice activists and pioneers Loretta Ross and Peggy Saika. Finally, this section includes biographies of Florynce Kennedy, an early member of the National Organization for Women, prolific reproductive rights attorney, and foundational activist; and Fannie Lou Hamer, an iconic civil rights activist, organizer, and visionary radical.

- Shirley Chisholm, Unbought and Unbossed

- Tiffany Diane Tso, “5 Reproductive Justice Advocates to Know This Asian Pacific American Heritage Month,” Rewire News Group

- Jaimee A. Swift, “Honoring a Reproductive Justice Pioneer: An Interview with Loretta J. Ross,” Black Women Radicals

- Loretta Ross Interviews Peggy Saika, 2006. Smith College Special Collections, Voices of Feminism Oral History Project

- Sherie M. Randolph, Florynce “Flo” Kennedy: The Life of a Black Feminist Radical

- Keisha N. Blain, Until I Am Free: Fannie Lou Hamer’s Enduring Message to America

IV. Core Texts: Reproductive Justice in Context

The texts in this section of our syllabus provide vital context for the reproductive justice movement as it moved through the twentieth century. It begins with law professor and scholar-activist Dorothy Roberts’s groundbreaking Killing the Black Body: Race, Reproduction, and the Meaning of Liberty, a text that grapples with the long history of assault on Black motherhood, reproduction, and freedom. It also includes Patricia Zavella’s study of the ways that activists have put reproductive justice principles to work within grassroots movements and Radical Reproductive Justice: Foundations, Theory, Practice, Critique, a reader in which leading activists and scholars explore how the reproductive justice movement has changed and grown in the decades since the founding of SisterSong. Essays within the volume expand on vital issues within the movement, including trans healthcare, immigration detention, reproductive justice within the prison system, maternal mortality, and reflections from founding mothers of the movement on building an intergenerational movement. An article from geunsaeng ahn further reflects on the experience of providing doula care to incarcerated individuals as a practice of care and liberation. Finally, this section also includes suggestions for further reading, from primary sources to articles, compiled by Jaimee A. Swift of Black Woman Radicals.

- Dorothy Roberts, Killing the Black Body: Race, Reproduction, and the Meaning of Liberty

- Radical Reproductive Justice: Foundations, Theory, Practice, Critique ed. Loretta J. Ross, Lynn Roberts, Erika Derkas, Whitney Peoples, and Pamela Bridgewater Toure

- Patricia Zavella, The Movement for Reproductive Justice: Empowering Women of Color through Social Activism

- geunsaeng ahn, “Abolition Is Not a One Time Event: Prison Doulas as Catalysts,” The Margins

- Black Women Radicals, “Reproductive Justice: A Reading List”

V. Memoir, Fiction, & Poetry

Feminist authors have long given voice to the lived experiences of navigating reproductive healthcare, family formation, and the possibility of feminist utopia within the context of a world marked by patriarchy, racism, and unfreedom. The selected works of fiction, memoir, and poetry below give voice to the varied and rich experiences of abortion, miscarriage, navigating birth control, and being embodied; they are only some of the rich and varied contributions to this genre, but they have helped the contributors to this syllabus contemplate the nuances inherent in navigating questions of biology and gender, make room for the the complexities of grief and joy that often live alongside each other, and imagine new worlds and ways of being.

- Toni Morrison, Beloved

- Gwendolyn Brooks, “the mother”

- Rokeya Sakhawat Hossain, “Sultana’s Dream”

- Mieko Kawakami, Breast and Eggs

- Mia Alvar, In the Country

- Kay Ulanday Barrett, More Than Organs

- Shivana Jorawar, “Why My Hinduism Includes Feminism and Abortion,” Bustle

VI. Reproductive Futures & Open Questions

The movement for reproductive justice continues to grapple with new questions prompted by globalization, climate change, structural adjustment, and technological advances in reproductive technology. This section addresses reproductive futures through readings focusing on gestational surrogacy on the global scale, the financialization of reproduction, and a potential framework for reparations for harms experienced by those who have survived forced sterilization programs.

- Kalindi Vora, “After the Housewife: Surrogacy, Labour, and Human Reproduction,” Radical Philosophy

- Michelle Murphy, The Economization of Life

- Michelle W. Tam, “Queering Reproductive Access: Reproductive Justice in Assisted Reproductive Technologies,” Reproductive Health

- Alexandra Minna Stern, Nicole L. Novak, Natalie Lira, Kate O’Connor, Siobán Harlow, and Sharon Kardia. “California’s Sterilization Survivors: An Estimate and Call for Redress,” American Journal of Public Health. Vol. 107. Issue 1. (2017), pp. 50-54.

This syllabus was written by Salonee Bhaman, but functions as a collective document with significant contributions and editing by Tiffany Diane Tso. It drew from several previously assembled sources, including the Reproductive Justice Reading List compiled by Jaimee Swift for Black Women Radicals.