A mysterious black poster sends one Columbia University student down a transnational college application rabbit hole.

February 24, 2015

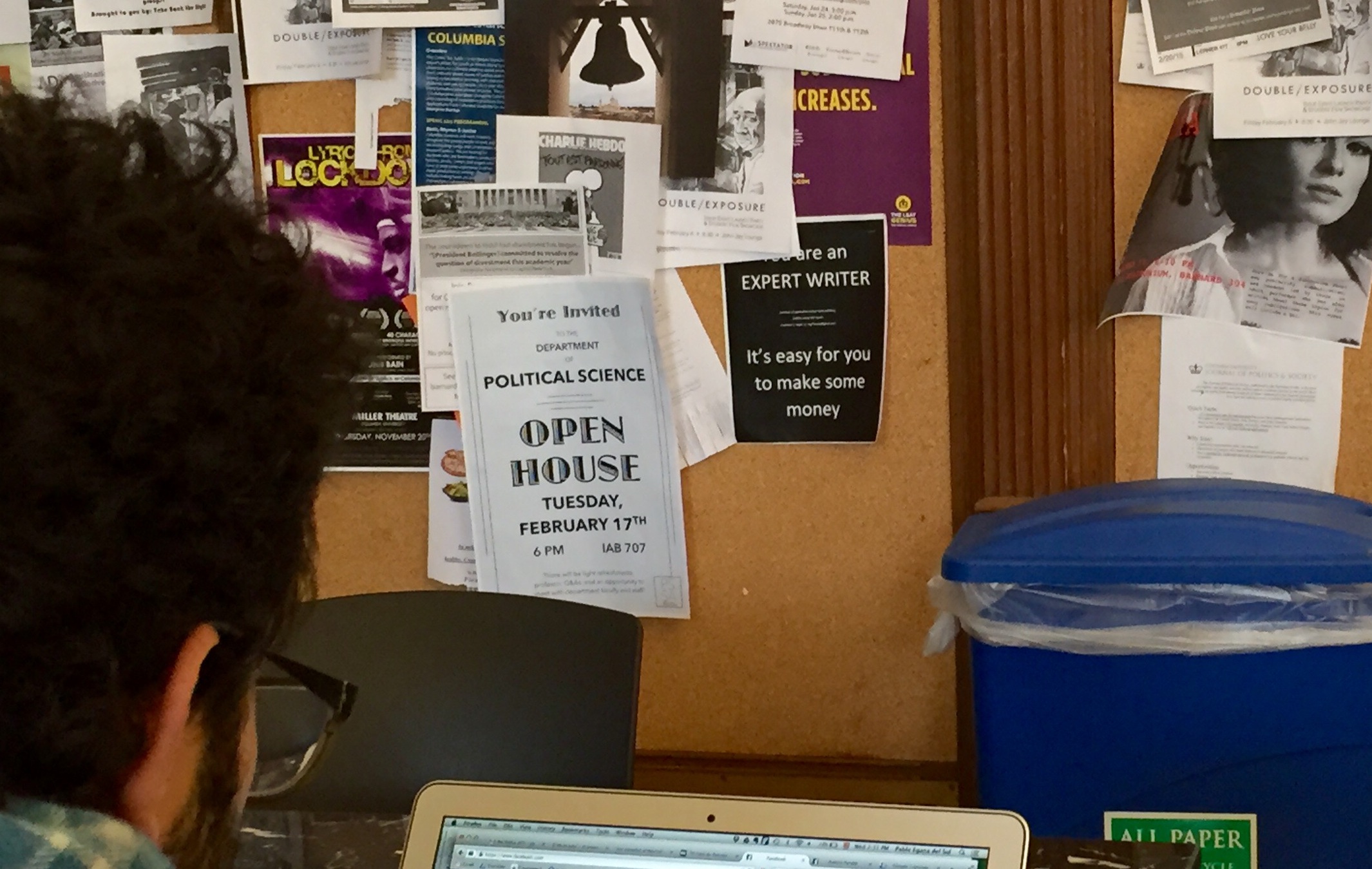

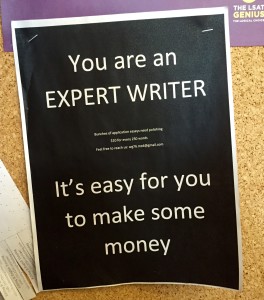

Every day Columbia University’s Butler library is abuzz with hundreds of frantic students scuttling in and out, backs bent under textbooks and countless cans of Red Bull. They dash past advertisements for club meetings, tutoring services, and the occasional plea for an Ivy League egg donor. None seem to notice the curious all-black 8.5 x 11 flier taped to a nondescript corner.

The flier has no image on it, only large white letters proclaiming, “You are an EXPERT WRITER. It’s easy for you to make some money.” I noticed. Intrigued, amused, broke, I emailed.

This was the beginning of my exchanges with “Old Friend,” an ambiguous avatar for the unknown sponsors of the poster. In answer to my email inquiry, Old Friend sent me this description of the work they do: “Thanks for your interest. We are a student group helping Chinese students to polish their application essays, such as personal statement, statement of purpose and CV. Our purpose is offering timely support for them to get high-quality polished essays. The polishing process basically includes correction of grammarian errors, decoration (such as selection of vocabulary, modification of sentences), and in general, transforming the original essay into a more professional and native language style.”

This response struck me as a bizarre mix of the humorous and the nefarious — the email equivalent of a Google translate app sporting a ski mask and sunglasses. Putting aside the irony of a self-proclaimed editing service sending out a message with numerous blatant grammatical errors, I was surprised by how little information Old Friend offered about him or herself, the students the company serves, or the general nature of their enterprise.

I felt as if I were on assignment for a top-secret spy operation, where my only job is to perform a discrete task, without knowledge of cause or consequence. As to the nature of the task itself, Old Friend’s description jumped from “polishing,” suggesting fine-tuning, to “transforming,” implying a total reinvention and even rewriting of the whole essay.

I felt as if I were on assignment for a top-secret spy operation…

Old Friend attached a sample essay with edits, meant to serve as a model for the work expected. True to the description, the editor had indeed transformed the essay. Bright blue comments in “track changes” left no sentence untouched. Many edits addressed blatant grammatical errors, some changed phrases to more colloquial sounding English; others still completely re-organized ideas. This level of editing rendered the original essay unrecognizable. I was astounded by Old Friend’s unabashed description of this process, which far exceeded “polishing.” The email had no big red flags that the service was ethically sketchy, but the whole exchange made my spine prickle.

Wondering whether this drastic degree of editing was typical of Old Friend’s company, I turned to fellow Columbia student Sasha Zeints, who has been editing essays for the same company for the past five months.

Sasha, too, was struck by how cryptic her interactions with Old Friend are. “I get paid in cash handouts outside Butler,” Sasha told me. “The one time it happened, he was like ‘are you Sasha,’ and I was like ‘yes,’ and he just handed me a wad of cash and walked away… I’ve never seen a face beyond the person who gave me the money that one time… I don’t feel like it’s a network, it’s just an email interaction. It’s very weird.” To me, this sounded more like the payment set up for a heist, rather than for an editing service. I decided to try to discover the face behind the friend.

I replied to the initial email with queries about the nature of their enterprise, attempting to break through Old Friend’s façade. I asked, “What is the name of your company and how long have you been in business? Approximately how many students do you service, and how many students would I work with? Are you working with other US Universities or just Columbia?” My questions received no answers.

The intense anonymity and secrecy surrounding editing essays is unlike any typical editorial process I’ve ever experienced. The point of an application essay is for a college to get to know a student. Presumably, an editor should be able to edit the essay more effectively if they know a student personally, and can tailor the essay to bring out that student’s best qualities.

I started to think that the mechanized, impersonal nature of Old Friend’s enterprise perhaps represents broader cultural differences between the Chinese and American college application processes. In China, university admission is based solely on the gaokao, a grueling exam that about 9.5 million students take every year. A recent New York Times article highlighted the extraordinary rigor and pressure Chinese teenagers face in preparing for the gaokao.

For many, the test determines the rest of their lives, whether they will attend a prestigious university or be sentenced to a life of manual labor and near-poverty. Even for those who pass the exam, choices are limited. Scores determine which university they will attend, and which subject they will study there. Maybe Old Friend’s anonymity and secrecy merely reflected this system where high stakes call for extreme measures.

The [gaokao] determines the rest of their lives…. Maybe Old Friend’s secrecy reflected a system where high stakes call for extreme measures.

In stark opposition to Chinese college entrance criteria, US universities employ a “holistic” approach, evaluating applicants on their high school grades, test scores, application essay, teacher recommendations, extracurricular activities, and demographics. Admittance has a great deal to do with individual students’ unique personalities. When my high school college counselor read over my admission essays, we talked about how I could best convey what makes me a “special snowflake.” She got to know me, and told me what aspects of my personality I should emphasize to colleges. The whole process hinged on her understanding me as an individual. This is perhaps why Old Friend’s undercover process initially struck me as so bizarre.

Aside from these cultural differences, I wasn’t totally convinced that Old Friend’s enterprise was ethically sound. Sasha had similar concerns: “I’m supposed to technically explain everything, and I do take the time to do that, I feel if they’re reading that it could potentially be a constructive process. But I think that I’ve rewritten a lot of these essays… I have given people direction that’s more about content and less about language.”

Whether or not the editor explains his or her corrections, and whether the student learns something from reading the edits, the bottom line is that students are submitting writing under their own name that isn’t actually their own words, or even ideas. Dishonest? Yes. Immoral? Perhaps. Un-American? No.

The American college admission system is by no means a meritocracy. I do not know a single college student who didn’t have someone else edit his or her application essays. Most had a college guidance counselor telling them which classes and tests to take, which schools they should apply to, what they should emphasize in their applications. Many had some type of SAT prep course.

None of these forms of assistance is as blatant as what Old Friend offers, but taken together, it’s evident that few students get into college completely on their own, and those who can afford to game the system by hiring tutors and college advisors will do so. As Sasha commented, “How many US kids wrote their own college essay completely? I’m not saying in terms of ideas, but people have tons of people read their essays. They’re paying for a service the way a lot of Americans do, and that’s how I’ve justified it.”

“How many US kids wrote their own college essay completely? They’re paying for a service the way a lot of Americans do.”

For the average undergrad, it’s also easy to justify working for Old Friend on an economic basis. Old Friends pays $10 for every 250 words edited. Sasha said that for her this works out to about $50 an hour, nearly five times what a typical student job pays. Editors can work from their dorm rooms, on their own schedules. The editing itself isn’t especially taxing — editors are mainly correcting basic grammatical errors to make the essays sound like colloquial English. In terms of payment, flexibility, and effort, this job is near unrivaled.

For student editors and student applicants, this system is a win-win. While I had initially balked at the mechanized anonymity of Old Friend’s enterprise, and dismissed it as bizarre and foreign, I ultimately realized that Old Friend is just working the system, providing a way for applicants to pull themselves up by their heavily-edited bootstraps. Colloquial English may still evade the company, but Old Friend definitely has gotten the hang of the American hustle.

However, the window for opportunity seems slim. After my probing email, Old Friend never responded to any of my inquiries about the position. I guess we aren’t friends anymore.