We’re closing out this year with our favorite graphic novels, chapbooks, fan fiction, poetry collections, and novels published in 2020.

December 14, 2020

We’re closing out this year with our favorite graphic novels, chapbooks, fan fiction, poetry collections, and novels published in 2020. Read about our picks below.

I searched through my iPhone photo library recently and discovered my late grandfather alive. In the photo, he was yawning, and I could see him again seated in his wheelchair in the nursing home. In her preface, Ancco recounts the happiness of seeing her grandmother before she had dementia while she scanned her “diary comics” Nineteen for the publisher Drawn+Quarterly. Ancco’s drawings record the familiar aches of young adulthood. You might say this graphic novel, translated by the talented Janet Hong, are about the pains of being pure at heart.

This is South Korea of the early 2000s. A time of flip phones, nary a smart phone in sight. Ancco captures the city skyline, alley ways, and busy crowds of Seoul with quick, layered lines and black blotches. A lifelong farmer, Granny’s face is heavily wrinkled, framed by her curly-permed hair. Students, who grow up with parents’ soju-fueled violence, also drink to forget intense academic pressures. A boy living with HIV contemplates the quiet tile-roofed, hanok-covered hills. There’s levity in stray dogs and accidental bad haircuts. Twenty-somethings eating in a loud, drunk bar on New Year’s. This is a past life I recognize too. When cities gleamed and the quality of light and mind made everything more beautiful and painful at once.

The thirteen stories took ten years to emerge into the English-language, and I’m all the more grateful for that satellite delay. “Through these drawings and words, I revisit feelings, people, a world that’s now gone,” writes Ancco. In 2020, Nineteen is a time capsule, a hit of nostalgia for a pre-pandemic youth.

—Esther Kim, Digital Communications Manager

In these days of mask-wearing and urging people to not gather in-person for the holidays, Zigzags by Kamala Puligandla is a welcome excursion to the before-times. The debut novel follows Aneesha who returns to Chicago in the summer between grad school years to write, look for a bike on Craigslist, have impromptu gatherings with friends, and live queerness expansively. Puligandla has a beautiful literary approach to friendships, one that is explored in this solo episode of the Heart podcast, and an energy that is fun, sexy, and intellectual that buzzes in this book trailer. Reading, I imagine Aneesha and her crew enjoying long nights at dive bars and talking into the late night, I imagine their unmasked mouths moving, eating, drinking, laughing. But for this reader, Puligandla’s novel evokes even deeper before-times of those summers in one’s twenties, where friends are the chosen family, and the friendships we cultivate become the way we navigate the world and who we are becoming—and maybe who we’ll become again, after all this, this, this—

Within the deluge of thrilling debuts in 2020 are two more—George Abraham’s poetry collection Birthright and Sejal Shah’s essay collection This Is One Way to Dance. What struck me is what is revealed about the writers’ process: Shah’s dating each essay which makes the collection operate as a personal archive of her writing, and Abraham’s mental diagramming in the final pages “Map of Home” which jostles themes of home, the memory of Nakba, and the erasure of archives.

—Swati Khurana, Flash Fiction Editor

One of the first books I read during the early days of lockdown in New York was Sabrina Imbler’s Dyke (geology). During a period of total discombobulation and disconnection from my self, my life, and my home, Dyke (geology) offered a radical, queer vision of the relationship between the body—and its simmering, erupting desires—and the earth itself.

I loved Natalie Bakopoulos’s novel Scorpionfish, about a women who, after the unexpected death of her parents, returns to Athens where she spends a summer coping with her grief, new, unspoken desires, and the changing face of the city she no longer lives in, but considers home. I read the novel in the middle of summer, when the few times I got to be with other people was during protests across New York, and I took great comfort in Bakopoulos’s precise and moving depiction of friendship and connection in a city wracked by political crisis.

To close the year, I picked up the new edition of John Edgar Wideman’s Philadelphia Fire, an autofiction account of a man writing about the wreckage of the 1985 MOVE Bombing. Wideman’s sentences are unreal in their beauty and clarity, and the novel reckons with state-sanctioned violence against Black revolutionaries and what it means to fictionalize these events. “I want to do something about the silence,” says Wideman’s stand-in, Cudjoe, a line that to me, encapsulates what I needed from literature this year.

—Yasmin Adele Majeed, Editorial Coordinator

I think of Lee Hyemi’s Unexpected Vanilla, in translation by So J. Lee, as a kind of hydration after the extended hangover of this year. The poems, which have been called surrealist and sensual, are what I’ve been turning to when feeling life-parched by the constant interventions in intimacy produced by screens and masks, as well as those greater interventions produced and reproduced by gender binaries and heteropatriarchy. “I created a seam as if it were new textile”—the poems feel enmeshed in this habitat of the seam: a place of punctures and exchanges, a translated place that is one and two at the same time. The poems are intimate, delicious, turning away, arriving. They ask: what if everything I see and feel didn’t already have a word box around it? How would I call the names of desire in a language that didn’t yet exist, when desire is punctuated by the grief it does not refuse to accept as part of itself? “Did someone pluck your tongue and plant a young fish in its place”?

—Kaitlin Rees, Asia Literary Editor

For me, Mexican Gothic answered questions I didn’t even know I carried for well over a decade: What if the women in Charlotte Perkins Gilman’s “The Yellow Wallpaper” were real? What if we could speak to them? What have they seen? And what do they have to say?

Set in 1950s Mexico, Mexican Gothic invited me into a world of supernatural horror that validated and upended some of my worst fears planted in my mind since I first read “The Yellow Wallpaper” as required reading in twelfth grade English. I was seven months pregnant at that time, and “The Yellow Wallpaper” terrified me. From the gaslighting to the powerlessness, it left me wondering what awaited me postpartum. But with Mexican Gothic, Moreno-Garcia’s protagonist fights back. The heroine, Noemí Taboada, is smart, self-aware, and confronts these systems that perpetuate violence, colonialism, and trauma. Despite moments of self-doubt, she challenges the menacing patriarch. And Noemí will not stand for the cycle of oppression to go ignored, or remain unchecked and left to fester.

What I love most, and why I highly recommend Mexican Gothic, is that Moreno-Garcia compels us to listen to the women in the wall. To witness their story, their origin, their pain. And with Noemí, we maintain autonomy that these toxic cycles so desperately want to pry away.

—Emperatriz Ung, Margins Fellow

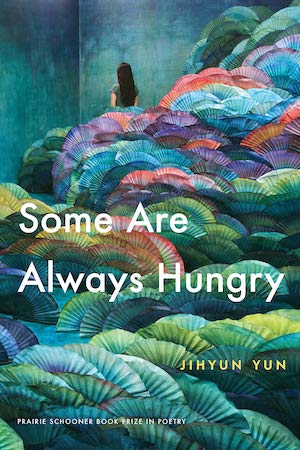

Some Are Always Hungry was released this September and stands as one of my favorite collections of poetry I have ever read (along with My Baby First Birthday by Jenny Zhang, which was also published earlier this year). I read the entire collection in one sitting with my knees to my chest on a creaky desk chair, taking and sending photos of each poem as it caught my breath. In her poem “The Daughter Transmorphic,” Yun writes, “A matrilineage expunged / and covered in moths / mouthing what’s left. / Flip the page. Gone / is the matriarch. / Close the book / and blood seeps / between chapters.” This book, though, recalls lost blood, hungry for its memory and sustenance.

Yun’s poems are both tender and taut in their tracings of blood-history (blood-body, she says in one poem, and I write it on a post-it), desire, lineage, and still, still, joy. Her multi-form poems, from prose to triptych to recipe, push us to enter each page differently realized and more alive in how we pursue joyfulness, that there is release alongside tension when we walk back through time. Every time I re-read a poem or a section, I find another line that’s closely in conversation with a line twenty pages from it (like poems of “Immigration” as near bookends!); Some Are Always Hungry reminds me that poetry holds—us, our blood, our hunger, and our hope.

—Yi Wei, The Margins Reader

“Neko Atsune” by snailieshell is a 180k word/79 chapter work of art that began in 2015 and ended just this year in 2020. What a ride! As snailieshell wrote this, they’ve graduated from school and gotten married. The story itself is the story of a small cat hybrid named Min Yoongi and a freelance website builder Park Jimin. Jimin takes Yoongi, who has endured a lot of trauma, in. The story is about healing, learning consent, and institutions. It’s a comforting read for anyone who needs a hurt/comfort journey.

—Ace Yang, Youth and Community Outreach Coordinator