The legacy of multiculturalism and what’s left of third-world solidarities.

March 18, 2014

The Counterculturalists is a new series in The Margins that looks at Asian American or ethnic identity as an alternative, rebellious, uncategorizable subculture, an avant-garde in both politics and aesthetics. Through interviews, original essays, multi-media, and criticism, we’re featuring writers and artists whose work calls us to the margins. First up is cultural critic and historian Vijay Prashad. Check out more in the series here.

“We are seduced by Obama’s beautifulness and the way he speaks. But these are imperialists,” chuckles Vijay Prashad at an AAWW talk in 2011. “He’s just such a sophisticated imperialist.” Prashad, dressed in a black T-shirt bearing the text “Gaza on My Mind” in both English and Arabic, speaks with the ease and congeniality of a stand-up comic. “Bush was an idiot imperialist, but this guy is so sophisticated,” he continues. The crowd laughs. “I’m looking forward to some lunatic coming back. It’s so much easier.”

We begin our series “The Counterculturalists” with Vijay Prashad, the prolific historian, journalist, and political commentator whose work you are as likely to encounter on the syllabus of your Marxism in the 21st Century course as on the homepage of progressive news sites like CounterPunch or Frontline. For 15 years, Prashad has embodied counterculturalism by eschewing traditional modes of inquiry and disciplinary boundaries, engaging and contesting histories of power, politics, cultural exchange, race, and occupation across time and place. Whether in open forum Q&As, journalistic editorials, or his nonfiction works, Prashad’s politics are informed by both the scope and specificity of his worldview: he is equally at home discussing the intricacies of the Syrian civil war as the anti-Blackness implicit in the model minority myth; equally biting in his critique of the Indian and Indian American communities’ shift towards conservatism amidst post-9/11 xenophobia as in his condemnation of Israel’s occupation of Palestine; equally nuanced in his exploration of histories of Third World solidarity as in his characterization of the Obama-era rhetoric of post-multiculturalism.

Prashad rejects contemporary cliches of diversity, multiculturalism, and post-racialism—his work pushes us beyond romanticized notions of racial, social, economic and gender-based “progress” to illuminate the structural inequalities that define the daily lived experiences of marginalized peoples the world over. With brutal honesty, Prashad depicts a world that is post-multicultural but certainly not post-racial; post-colonial but assuredly not post-imperial. Yet, the sometimes-grim reality of the pasts and presents Prashad depicts is tempered by a sort of humanist optimism. While The Karma of Brown Folk (2001) traces the complicity of some Indian Americans in the use of model minority rhetoric as a weapon of anti-Blackness, Everybody Was Kung Fu Fighting (2002) offers a historical rubric for Afro-Asian solidarity and exchange. While The Poorer Nations (2013) traces the bleak history of economic neoliberalism and its impact on the Global South, alongside The Darker Nations (2007) it also highlights the inspiring, if flawed, Third World solidarity movements during which post-colonial nations envisioned a reorientation of global power that, though ultimately unattainable in their own moments, offers exciting and evocative prospects for the future.

On Prashad’s The Poorer Nations, writer and journalist Amitava Kumar remarked: “Prashad is our own Frantz Fanon. His writing of protest is always tinged with the beauty of hope.” Ultimately, it is those tinges of hope that transform Prashad’s work from pure scholarship to a truly radical political project.

Writer and legal scholar Aziz Rana sat down with Prashad to talk about the end of multiculturalism in the U.S., race post-9/11, and what’s left of third world solidarities.

Aziz Rana

One of the most compelling or moving claims that you make in Uncle Swami, but also that you’ve written about previously, is the idea that with Obama’s election as president, a specific age came to a close. So, the age of multiculturalism ended, and we now live in a post-multicultural era. But that doesn’t mean that that’s the end of racism or that we now live in a post-racial America. Maybe talk a little bit about the age of multiculturalism that you say began or reached full force in the eighties. What does it mean that it’s over? What did it stand for? What were its strengths and limitations?

Vijay Prashad

You know, for that, it’s a good idea to go back to the mid-1960s, when the Civil Rights movement ended. What the movement was able to gain was the power of people who had been treated as second-class citizens to now occupy space in society, to go as they wanted, particularly in public space—to take their seats anywhere on the bus, et cetera—to vote, to have political rights, to stand before a judge in a courtroom and be treated like anybody else. These were substantial victories, but they were largely in legal, political and to some extent in the social domains. Right after the mid-1960s when these victories happened, one major direction to further the Civil Rights movement was taken by activists who created the Poor People’s movement, and among them, of course, was Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. Their idea was, it was not sufficient to let the question of civil rights remain at the level of politics or the law; it must be taken into the realm of the economy. They wanted to force a conversation about Jim Crow conditions in economic life. At the same time, people in power obviously were not happy to have that kind of conversation. They had come to terms with the new dispensation, they had accepted it. They said, “Okay, fine, the vote,” “Okay, fine, you can stand before a judge in the court.” But they didn’t want to have a substantial conversation about economic life and about a kind of Jim Crow economy.

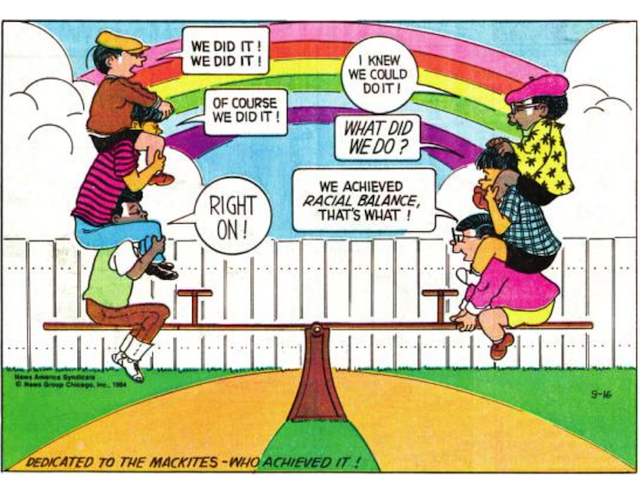

So interestingly—and this is not a conspiracy, but—at a slow process, the conversation moved in the direction of culture rather than economy. And we get some institutions of American life where the issue of culture becomes more important than [other issues]. In other words, multiculturalism, as it began to develop (in fits and starts, but it developed into a coherent ideology) suggested that the economic or the social structure, these things will not be changed. These things can remain as they are. But within these institutions—these cultural, social, even economic institutions—there should be an opportunity for talented people of color to rise.

AR

Yes.

VP

There was to be no change in these institutions—it was simply that talented people of color can rise in them: that was multiculturalism. Therefore, in the ’90s and 2000s, one saw talented people of color enter corporations, begin to lead them and eventually be on the Supreme Court, enter the military and become the head of the Joint Chiefs of Staff. And then, of course, the very highest office in the land: the presidency. And that was, in a sense, the end of multiculturalism. You know, how many more glass ceilings can you shatter, without changing the structure, once you have the presidency in hand? But I think the presidency going to Obama was confusing to a lot of people because they didn’t see Obama’s victory for what it was, which is ending the era of multiculturalism—that is, the era that said, “We keep all institutions as they were in Jim Crow times, okay, [but] allow talented people of color to rise in them.” They didn’t see that that’s what he had vanquished—he had ended multiculturalism. What he hadn’t ended, is a much more enduring problem. And that is racism. Racism is the kind of institutionalizing quality that’s structured into those institutions, which we were told cannot be changed. We were told we cannot change the way the military functions, the way corporations function, the way cities operate. What we can change is we can allow the talented among you to rise in these same institutions. So racism was kept intact; multiculturalism allowed some people rise. With Obama’s victory, multiculturalism ends, but racism remains, and that’s basically the story that I wanted to tell.

There was to be no change in these institutions—it was simply that talented people of color can rise in them: that was multiculturalism.

AR

It’s incredibly powerful. But I wanted to pick up on something that you hinted at when you were talking about Martin Luther King and the Poor People’s movement. You emphasize that in the last years of Martin Luther King’s life, he understood race to be deeply interconnected with issues of class, and the need for African Americans to think of black freedom as a project that’s inclusive of immigrants, non-whites from lots of different backgrounds, as well as poor whites—and also to understand it as tied to issues of American power abroad. That racism and imperialism, if not two sides of the same coin, were also deeply interconnected. All of these are arguments have essentially disappeared from collective memory. Today, Martin Luther King is essentially the patron saint of a kind of colorblind America [about which Supreme Court Justice Antonin] Scalia and many other conservatives can say, “Well that’s what the end of racism is; it’s not talking about race.“ And you know, there’s that quote from the “I have a dream” speech that’s almost always excerpted as part of our popular discussion. But actually, what he was writing, saying, what he was even doing before he was assassinated (he was in Memphis for a union organizing action), all of that’s basically been disappeared, the fact that he was a controversial figure when he died. Why do you think the collective memory has disappeared and how is that tied to multiculturalism? What were the forces that transformed our collective memory of the Civil Rights Movement?

VP

Let’s say there are two ways great heroic figures get remembered. One way is if your project is fully won, and then you are treated as, maybe, the godhead of a new kind of world, a new dispensation—the way, in America, people remember George Washington—he never tells a lie, he’s an upstanding person, he’s a patriot; he did all that kind of stuff. So he stands in for the nation, in a way, in memory. Then, there is the person whose project is not fully won; it comes to a certain point and it gets blocked. And there the figure of Martin Luther King just as well could be [compared] to Gandhi. Gandhi has the same kind of remembering happen to him: so your project is partially won but it’s not realized; [and] you have a deeply ideological critique of society. Whereas, say, George Washington doesn’t have a deeply ideological critique of society; it’s much easier to memorialize him and make him self-evident with the nation. Gandhi, also kind of treated as the founder of the nation in India, father of the nation, had a much deeper ideological critique of society [that] could not be fully grasped. Easier to make streets named after him than actually take his ideas seriously.

The central part of [King’s] projects did come to be. The Civil Rights Act was passed, the Voting Rights Act…. But then, as you say, King deepens everything. I mean, his speech on Vietnam is called, “A Time to Break the Silence.” In other words, he was making an argument [about] whether the country has been silent about the crimes of imperialism or whether he has been silent in the service of a much simpler project, which was to end Jim Crow. But, having now vanquished Jim Crow, having reached a point where American ideals had become self-evident to itself—you know, America was founded on the idea that everyone was to be equal, et cetera, and the civil rights movement simply brought into the world America’s own ideals—suddenly King would say, “Now it’s time for me to break the silence. I have been silent about something else, which is that maybe this American ideal is actually contradictory. We not only have this idea that people should all be equal, but we also have a kind of imperial messianism—we‘re going to go overseas and bomb people in the name of freedom.” And he calls that speech “A time to break the silence.”

When that speech comes out, King sets himself outside the boundaries of acceptable, liberal political discourse. No more is he simply saying America must live up to its ideals. Now, he is saying, what kind of moral morass are we in? In fact he says “a country that spends more on its military has reached the point of moral decay.” I mean, his has been a fundamental critique of the entire American system. Obviously, therefore, when they make a King museum or statue, they don’t put those quotes on there. Those quotes are not celebrating the American consensus. Those quotes are saying there is something deeply wrong with our attempt to go and bomb other countries, with our acceptance—our sanctification—of high levels of inequality inside the country. In a sense, the King example tells us a lot about what is allowed as political speech in America and what is seen as incomprehensible. If one starts to talk about imperialism—the political elite has so captured the space for discussion, that this stuff sounds totally incomprehensible. Therefore, the King that’s remembered is the King that is within the boundaries of American consensus, and the King that cannot be remembered is the King that breaks out of that consensus. But I find that the second King is the much more interesting one because he is the one with the real challenge to the America we live in today.

AR

I wanted to switch gears a little bit and talk a bit about race post-9/11. If Obama’s election doesn’t mark the end of racism, could you talk a little bit about how the attack on 9/11 shifted the terrain of our contemporary racial conversations and the ways in which that post-9/11 set of discourses is connected today to the meaning of race and racism?

VP

This comes to the heart of how one understands race, and what race is. I remember right after 9/11, people, especially my African American friends said, “Well, the heat is off us, for maybe twenty seconds, and it’s on you now. You will be pulled off the train. You look like a terrorist, it’ll be on you.” But of course, maybe their statement that it’ll be off them for ten minutes was premature because five minutes later, Driving While Black is back. Five minutes later, police repression in black communities, in Latino communities, in these communities in America where the political economy has failed utterly, has thrown people out. I’ll come back to that in a minute.

The way to understand race is: Race is not just about prejudice, not just about interpersonal relations. Race is a built-up, historical way in which some groups have nominated themselves to the perch of superiority, have, over at least a couple of hundred years, been able to monopolize the wealth of society; they’ve been able to claim and take property; they suggest that, well, since they have property, they are able to commission artists; they are able to have their children go and have leisure activities; therefore they are cultural, [and] so they are culturally superior. These are the same people, who, using that sequestered social wealth, are able to have political power. They are the ones who are able to coordinate or control the way in which conversations are framed, because they’ve taken all this social wealth. They are the ones able to even have influence in how history is told.

The King that’s remembered is the King that is within the boundaries of American consensus, and the King that cannot be remembered is the King that breaks out of that consensus.

If that is the case, you can’t just change the target of racism overnight. In the 1970s and ’80s factories began to close in the United States as large numbers of mainly black, Latino and white workers were thrown out of their jobs. There became a kind of jobs crisis in America. No longer were these people needed by the economy. Jobs went overseas, the new form of growth in America was through patents on inventions [and] biotech developments, and the Internet became a place of money-making—but none of these things required factories in the United States. Apple makes everything in China, for instance; there are no Apple workers in the US making anything. So, very large numbers of people had become utterly disposable. As a result of their disposability, they had to be garrisoned in two different places: one was, because of the drug laws, vast numbers of black and brown people thrown [and] warehoused in prison. And secondly, their own neighborhoods became open-air prisons.

I live near Springfield, Massachusetts; it essentially is an open-air prison. There are police all around. It’s hard for people in that neighborhood to walk outside without being harassed. This is the nature of today’s racism. These are millions of people who have been cast out of American society, and they are garrisoned. After 9/11, it was not that these people were suddenly free, and the target was going to [be] people who looked like terrorists. Nonetheless, a new enemy had appeared. (That new enemy made its appearance in the 1990s, but after 9/11, certainly it was much sharper.) And the state, using all its experience against black and brown people and all its experience garrisoning those populations, went after people who looked like terrorists. And that was an extraordinary moment for the South Asian population, because South Asians, since the 1960s, had lived here with the expectation that we were essentially whites on probation: if we worked hard, if we didn’t complain, we would be treated, even though nobody was going to mistake us for white, essentially as whites. On 9/11, our probation was revoked. It was a huge surprise for the community. Yet it was nothing like the kind of systematic racism experienced by black and brown people, because still, sections of South Asians had the privileges of middle-class life, had privileges of their training, et cetera. That didn’t protect them fully, it didn’t mean that you had the same kind of highly racialized existence. What it did mean was that these racializations took place inside. People began to feel cut off from society, people began to internalize fear. I remember the first few years after 9/11. Most of the people I knew—very confident people, professionals—were afraid when there was a knock on the door. There was a sense of being in terror about what was going to happen to you, and there I thought that the parallel was less with the racism against black and brown people and more with the way in which McCarthyism functioned—where people, progressives who were on the left in any which way, were under constant surveillance and many of them arrested and thrown in prison very unjustly, for no good reason at all. So 9/11 had a huge impact on South Asians. We didn’t expect it to happen, not in this way, and when it did happen, there were a lot of very peculiar responses, the leading one of which, of course, was fear and retreat further away from society.

This is the nature of today’s racism. These are millions of people who have been cast out of American society, and they are garrisoned.

AR

One of the things you talk about [is] how, in some ways, it also further broke down classic third-world solidarities, not just among black and brown, but also among different shades of brown. You have this really interesting anecdote where you say that a rumor swept through the community in the US, that the Indian embassy in Washington had advised Indian Americans to wear bindis to avoid being seen as Arab, i.e., if you can show that you’re not Muslim, that you’re Indian, then you’re the right kind of brown color. You see this idea, too, in the emphasis from various lobbying groups, as well as in elements of the Indian government, that the US and India are fighting the same enemy. They’re both fighting [an] undifferentiated terrorist threat. Could you talk a little bit about this focus, which is, in a way, a deeply nationalistic ethos? It’s nationalism being used as a way to destroy some classic third-world solidarities. How did it emerge? How is it tied to the construction of Indian Americans in the US as model minorities? This is something you discuss at length in The Karma of Brown Folk, but what is the link between the two?

VP

The first thing people should know is that there are more Muslim citizens in South Asia than anywhere else in the world…. South Asia is a place that is extremely diverse in its religious scope. These are populations that have been there for centuries. This is a very rich and vibrant kind of social community. So that’s the first thing to recall, that it’s amazing how people assume that a country like India is a Hindu country. It’s not a Hindu country firstly because the category Hindu is as loose as the category Muslim. It’s an incredibly diverse world, but that doesn’t mean these social diversities map themselves out well at the political level.

It’s amazing how people assume that a country like India is a Hindu country. It’s not a Hindu country, firstly because the category Hindu is as loose as the category Muslim.

For at least sixty-odd years in India, there’s been the growth of the Hindu right, a kind of fascistic movement, which has its own contours around the idea of Hindu religion [and] culture. In some ways they are akin to a kind of section of the Zionist movement, which also has this idea that its state needs to be a Jewish state—not a secular state, which is a homeland for Jews, but a Jewish state, a state that is committed to certain religious principles and one way of existing within the society governed by that state. So this Hindu nationalist movement has had a pernicious impact on the Indian community in the US for at least 25 years. It has been able to effectively insinuate itself into sections of the community by using guilt, saying, “You abandoned your country, but we know a way for you to give back.” Secondly, it has been very clever in using the [territory] of multiculturalism, saying, “Well, since everybody has a culture in this society, why aren’t you proud of your Hindu culture?” And they’ve used this space of multiculturalism to push the idea of an organized Hindu culture.

In the 1990s when the US deviated out of the Cold War framework, this new enemy emerged, the enemy of the Muslim terrorist. When the Oklahoma bombing happened, despite the fact that it was a white supremacist who did that bombing, the immediate assumption was, “Oh, it was a Muslim.” The idea [was] that the Muslim terrorist had become mundane. At that time, during that decade of the 1990s, this section of the Hindu right had begun to articulate a politics saying that, “We as Hindus in India, experience Muslim terror in the same way as Jews do in Israel, and in the same way the Americans are starting to do.” And they wanted to put forward this great historical alliance between the United States, Israel and India. And they succeeded, to a great extent. For the first time in Israel’s history, its head of government came to India—Ariel Sharon traveled to India in 2003. He was to give the important speech on 9/11, 2003, in Delhi. A very charged, symbolic kind of alliance was being created. And the enemy of all this was some mythical character called “Muslim.” That was [a] very pernicious development that took place.

And underneath that, as you say, was this model minority idea, not only [that] Indians are a minority [group] that doesn’t require social welfare, doesn’t require handouts, [that] can do it on their own, but of course, also, [that] Jews in America don’t require handouts, have done it on their own. This idea developed that these are communities that have small-business savvy. In the US, there’s nothing greater than championing small business, even though the actual economy is governed by massive monopolies. There’s still a great fantasy about [the US being] a country of small business. You’d see congressional figures coming to Indian and Jewish American gatherings and talking about how these two communities had so much in common. I found this very disquieting because it creates a politics that marginalizes the actual lives of people and doesn’t take seriously the fact that, as I started saying, in South Asia we’ve got the largest population of Muslims—and [that] people are not Muslims 24 hours of the day. They are your neighbors, they are teachers, they are people who irritate you, they are people who fall in love with you. I am not a man twenty-four hours of the day. I don’t walk around saying “I’m a man, I’m a man.” You forget sometimes, then you have to find a toilet and you’re reminded. We are not always all our identities at the same time. We live complicated identities. And somehow this approach to 9/11—where this idea of the Muslim was the target—seemed to suggest that if you are a Muslim, you cannot live a complicated life. And I thought that was, not only socially very destructive, but a great lie, and dangerous.

You’d see congressional figures coming to Indian and Jewish American gatherings and talking about how these two communities had so much in common.

AR

One American example that you talk about, of the international connections between black and brown communities, and [of] this legacy that has slipped from the collective memory, is the experience of Kumar Goshal. Kumar Goshal is a great activist for Indian independence, but also a tremendous journalist, critic and commentator who spent the ‘40s and the ‘50s writing for the Pittsburgh Courier during a time when there was a vibrant black press. And his writing for the Pittsburgh Courier was an account of what was happening in India. You know, if you read The Economist, there will be a paragraph at the beginning on an election in Bolivia or Greece, [and] it’s just knowledge about a place that has no seeming connection to your own personal experience. That’s how the news is presented. Instead, what Gashal was doing was saying that it’s essential to understand what’s taking place in India because in a deep sense, the Indian experience of independence is tied to the black struggle in America and that these are two different moments in a global anti-colonial project. The fact that he’s writing for [a] black newspaper is key, and the African Americans understood those connections without Gashal having to state it explicitly, that these are linked historical experiences and that freedom for one required freedom for another and vice versa. You can’t have an end to empire without an end to racism at home, and you can’t have end of racism at home without a transformation in how European and American powers operate abroad. Where do you see these particular kinds of connections between the domestic and the foreign that play on traditional forms of third world internationalism? Where do you see a possibility for the revival of this type of politics?

VP

You know, they exist—they’re alive and well. For instance, in the black liberation tradition, there remains a very strong international understanding. Sometimes I don’t agree with it. For instance in the case of Libya, that strand took the view that Gaddafi was a heroic figure and needed to be defended against a kind of imperialist attack. So that strand remains; it’s there in the black liberation. It’s certainly there in the Latino political tradition. L.A. is a great example because you have this great Salvadorean population that’s acutely aware of the problems of empire and the kind of two-faced nature of American power. And then there’s the Syrian population in L.A., also acutely aware of the role of empire, the role of power, the role of money. So I’m just saying that there are pockets of populations, there are sections within communities, there are traditions that remain. The issue is these are all minority traditions in the communities and, they have not grown over time. So, take somebody like the minister Farrakhan of the nation of Islam. I would say Farrakhan’s view of Africa or the Middle East hasn’t kept up with the dramatic shifts in the Middle East over the last fifteen to twenty years. So what it means is that that internationalism can often be internationalism of regimes and not the people, whereas what we require at this time is an internationalism of the people, not necessarily with the regimes. The regimes have conformed themselves dramatically over the last twenty years. If we’re not aware of that, I think we can trap our own contemporary sense of internationalism. It’s a very serious problem. It’s not a problem only of credibility; it’s a problem of how we see people struggling for their own voice and freedom.

MORE IN THE COUNTERCULTURALISTS SERIES ON VIJAY PRASHAD:

“First Days in Radical America”: On Prashad’s memories of the student anti-Apartheid movement in the 1980s and learning how to live in the US