In Jersey City’s India Square, the Hindu holiday is tempered and celebrated privately.

November 14, 2012

I knew that something wasn’t quite normal when I looked down Newark Avenue and didn’t see any colored lights.

Red, blue, and yellow prayer flags dangled from the street lamps and power lines, and garlands streamed from a few of the storefront signs, but the street seemed subdued. “This is Diwali?” I asked my boyfriend. He shrugged. I felt fairly sure of the date but was confused enough to take a look on my phone. My search confirmed what I already knew. It was the weekend before Diwali—honored this year on November 13; by now, most Indian communities throughout the United States would be celebrating the “festival of lights” with street fairs, streamers, colored lights, dancers, and fireworks. But not this street. What had happened to Diwali? Had Hurricane Sandy put an end to the celebration in Jersey City’s India Square?

Diwali, the festival of lights, is among the most important festivals in Hinduism. It marks the end of harvest, and for some businesses, the end of the fiscal year. It’s a time for worship and renewal.

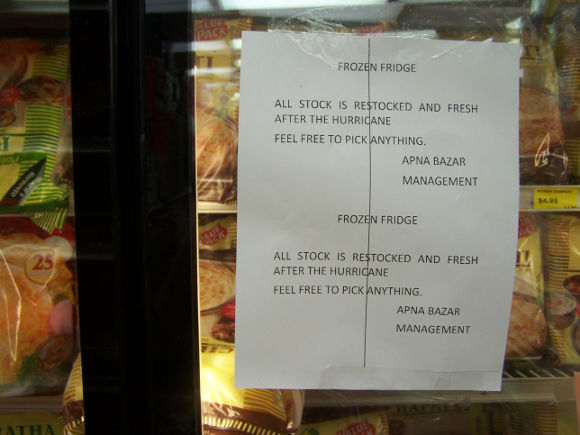

My boyfriend and I combed the streets, looking for signs of celebration. The area was bustling: couples lugged grocery bags nearly bursting with goods (restocking shelves, I imagined, after twelve days of shuttered grocery stores), while men and women gathered around the newsstands trading gossip. There were signs of a recovery. Generators stood in the streets, now unneeded. One store promised that the entire freezer section had been restocked. Trucks lined the curb as stores rushed to restock their shelves. But no sign of Diwali.

Jersey City’s India Square is housed in the Journal Square district in Jersey City. This “little India,” a concentrated block, isn’t as expansive as the one in Jackson Heights or as glitzy—and touristy—as Murray Hill’s. Restaurants touting dosa sit next to sweet shops. Stores hawk wares in three languages (but not in English). The markets offer Chinese Snow face lotion, bags of rice, puja thali, and brass polish. In the middle of the street is the Govinda temple; as you pass, you can hear the worship services piped through the sound system. Banners offer low rates on calling plans to India, Pakistan, and Bangladesh. It’s a working class neighborhood; the average per capita income in Journal Square is a little more than $22,000 (with 20 percent living under the poverty line). Half the neighborhood is first-generation immigrant, including a large Bengali, Bangladeshi, Pakistani, and Guyanese community.

I don’t live in Journal Square, my boyfriend does, but I’ve come to love this block along Newark Avenue. During Sandy’s landfall, Journal Square didn’t suffer the degree of damage that Hoboken or even Exchange Place did, but its residents lost power for twelve days.

I lived in Jackson Heights for five years, but this block, for me, even more than that neighborhood, embodies the pluck and resolve of the “little” community. Every other sign promises to serve in some way the peoples of “India-Pakistan-Bangladesh.”

And I knew the Diwali celebration would be important to the businesses on this block and the people living nearby. (Last year, the celebration, which lasted well into the morning, could be heard over a mile away on Van Reypen Street where my boyfriend lives.)

Diwali is “our Christmas,” the owner of Bengali Sweet Shop explained. “It’s our most important time of the year.” In his store, I noticed the trays of moti choor ladoo, kaju katli, kalakand, jalebi, and milk barfi. A good sign. Sweets are an important part of Diwali. For me, they mean boxes full of the sticky-sweet jalebi—my favorite—given as gifts by my friends. “We’ve lost a lot of sales. There would be big parties. Not this year. Everyone has suffered.”

Sunanda, co-owner of Silver World, a jewelry and sari shop on the avenue, was even more forthcoming. “Of course, we suffered losses. We were closed twelve days during our most important season.

“People don’t have money or time,” she continued. “They have to wait in line for gas. They have to buy food. Some are coming in to buy something small for their children. It’s going to take time. But we all feel lucky to have what we have.” She smiled at me and added, “The best thing you can do now is help save someone else.” And, in fact, that’s what all the merchants I talked to along Newark Avenue stressed. They suffered significant losses, but felt grateful to still have their stores, a livelihood, their lives. They believed the celebration had been cancelled willingly by the community, as an acknowledgement of the suffering of the city at large.

“People don’t have money or time,” she continued. “They have to wait in line for gas. They have to buy food. Some are coming in to buy something small for their children. It’s going to take time. But we all feel lucky to have what we have.” She smiled at me and added, “The best thing you can do now is help save someone else.” And, in fact, that’s what all the merchants I talked to along Newark Avenue stressed. They suffered significant losses, but felt grateful to still have their stores, a livelihood, their lives. They believed the celebration had been cancelled willingly by the community, as an acknowledgement of the suffering of the city at large.

Imagine having to dim the Christmas lights at Macy’s. No Santa Claus. No holiday display at Bloomingdale’s. But here in Journal Square, Diwali was cancelled out of respect. The businesses dealt with the losses. The residents gave up the opportunity to celebrate their most important holiday, so that they could demonstrate a larger solidarity with a city and state that has suffered.

The news isn’t all terrible. My boyfriend and I headed to Newark Avenue Tuesday night, the official date of Diwali. In one restaurant we found a small sign advertising a Diwali celebration the coming Saturday in Newport: “Part of Proceeds Going to Hurricane Sandy Victims.” That won’t help the businesses on Newark Avenue, but it’s something. My boyfriend and I bought a half-pound of jalebi—more than either of us could ever eat—and headed back home to celebrate Diwali privately, in our home, as so many other residents of Newark Avenue were doing that night.