How we perceive and write about climate change

March 30, 2023

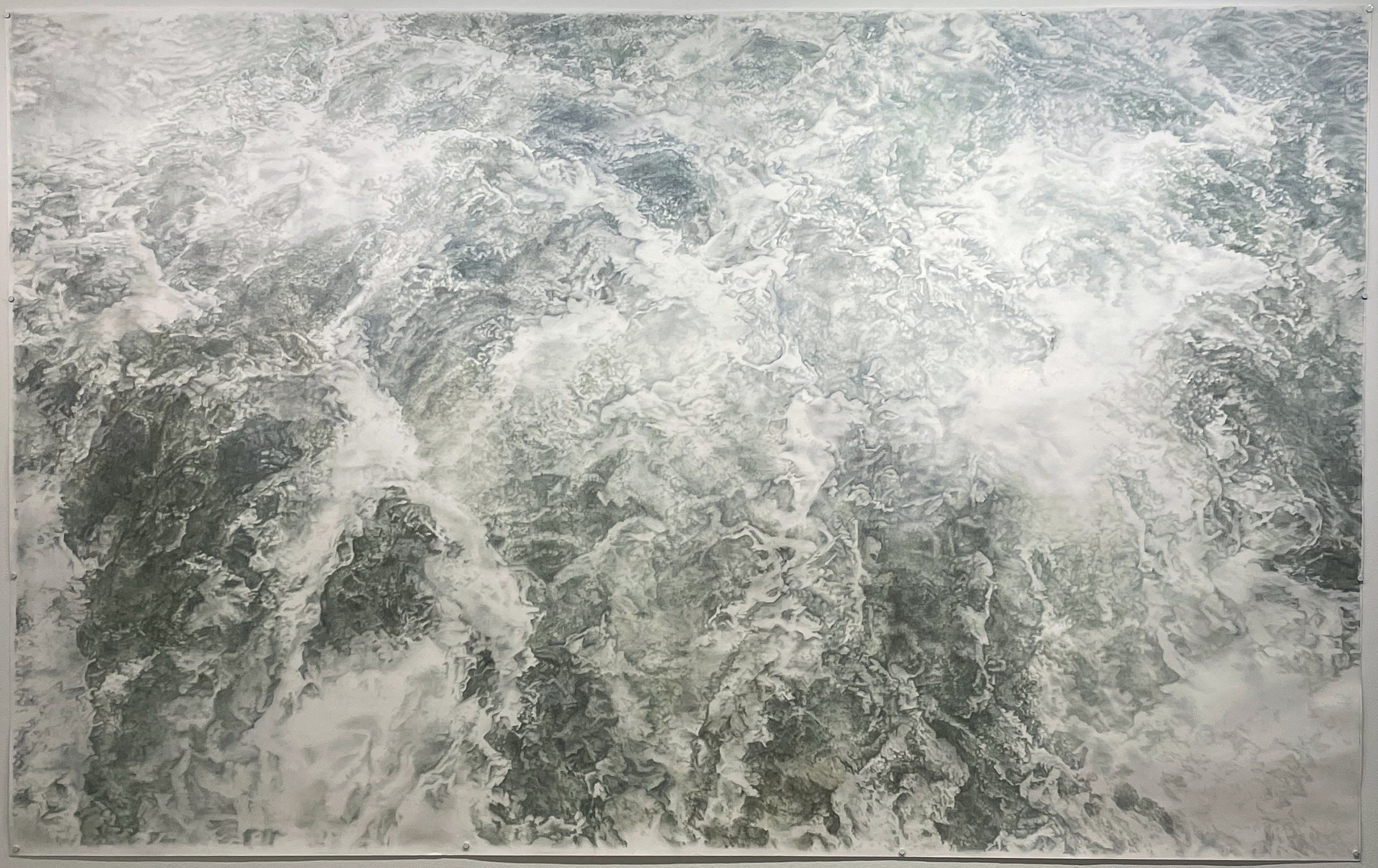

This piece is part of the Climate notebook, which features art by Katrina Bello.

The effects of climate change can be seen everywhere these days. Each season shows us how climate patterns have changed, whether it’s the Hurricane Ian sweeping across the American southeast and Cuba last fall, the floods that surged through Pakistan last summer, or the heatwave in India and Pakistan last spring. We see it in news reports, in messages from our family or friends. We feel it in the snow or rain or smoke that fills the air outside our homes.

The reality of climate change and the damage it brings is not news. But last summer, we at The Margins, under the leadership of our editor in chief at the time, Jyothi Natarajan, were energized to take on the topic after reading scholar Min Hyoung Song’s book of literary criticism Climate Lyricism (Duke University Press, 2022). We were taken with Song’s articulation of what can feel daunting and incomprehensible about climate change. “Too often, climate change is imagined as happening somewhere far away and in an always deferrable future, and as a result it is difficult to grasp the ways in which it is occurring in the here and now,” he writes. In the book, Song traces how writers engage with climate in the “here and now,” in everyday circumstances and particulars, and offers a mode of reading in which we can sustain attention to climate change and find shared agency to act for the better.

“Climate change needs a slower burn of attentiveness, a willingness to sit with discomfort that doesn’t fit too neatly into narrative plots, a returning again and again to contemplation,” he writes. Song shows that to pay attention to climate change also requires contending with “the legacies of conquest, racism, exploitation, and extraction that are everywhere.” He notes, “The phenomenon of climate change does not exist in isolation from these histories but is very much an inextricable product of them.”

Inspired by Song, we invited Asian, Asian American, and Pacific Islander writers to contribute work for a notebook loosely themed on climate. We asked for pieces not so much about climate itself, but about how we perceive, write, and talk about climate and the environment. The resulting collection of poems, personal essays, craft essays, speeches, reportage, and letters offers many ways of reckoning with our dialogue around climate change. Each piece is accompanied by artwork by Katrina Bello, whose intricate, precise drawings of natural textures and shapes resonate with the questions of scale that drive this notebook.

At the center of the notebook is a beautiful, far-ranging correspondence between Song and the poet and scholar Jennifer Chang, in which they analyze two poems—Agha Shahid Ali’s “In Search of Evanescence” and Shreela Ray’s “five virgins and the magnolia tree”—to meditate on the intersections of climate, migration, and the lyric. The pair considers how we perceive change across time and space—both in how our climate has changed and how displacement and migration has changed our sense of home—and how literature can voice and bridge those distances.

Fiction writer Talia Lakshmi Kolluri and poet Craig Santos Perez both contribute craft essays to the notebook about writing about climate change and the natural world. Kolluri looks to Ed Yong’s science journalism on the animal mind and Amitav Ghosh’s theories on climate change literature to imagine the perspectives of animals living through environmental crises. Perez, meanwhile, recounts how he “recycles” classic poems with language about climate change and how that language has seeped into his consciousness. “As I learned more about climate change, I started to notice changes everywhere,” he writes. “Changing temperatures, changing weather patterns, changing scientific data, changing political discourses. In the literary realm, the changing climate changed my poetry as I started writing more about climate change. Change, the word itself, appeared everywhere.”

Many poems in the notebook contend with the language we use around climate change. We invited poets Luisa A. Igloria, Philip Metres, Laurel Nakanishi, and JinJin Xu to write in the tradition of erasure and documentary poetics by choosing a text related to climate change and fashioning a poem from its language. Stemming from newspaper articles and political speeches and studies about land development, these poems reveal the language institutions, media, and the state use to describe or deny climate change. “As poets, we sometimes work with official, bureaucratic documents and language (or disinformation and conspiracy language), as a way of resisting the systems that produced those documents,” writes Philip Metres about his poem in the notebook. “They are not mere detritus to the systems of power—they are its proof, evidence of its power.” Elsewhere in the notebook, M. J. Cagumbay Tumamac, in a poem translated from Filipino by Kristen Ong Muslim, meditates on how colonialism and development of the Philippines has affected its languages. “Words cannot be owned / and neither can the land / according to the Tboli people of Maitum,” writes Tumamac.

The perception of climate change and its intersection with memory also surfaces across the Climate notebook. For many, part of perceiving climate change on an intimate, bodily level is to remember an earlier, different time. While reporting on indigenous fisherfolk in Mumbai, Astha Rajvanshi speaks to one fisherman who recalls his father teaching him how to fish nearly fifty years ago, when it seemed easy to bring in big catches. The fisherman does not expect to teach his children how to fish, now that the city is sinking and fish populations are declining due to overfishing and rising sea temperatures—changes that have deeply endangered the livelihood of many indigenous fisherfolk in the city.

This mode of understanding climate change is echoed in Masatsugu Ono’s essay, translated from Japanese by Juliet Winters Carpenter, about the seaside village where his parents live. He describes the recent rains and typhoons in the village as “beyond anything in Mother’s recollection.” He adds, “This little place that no one pays any mind to, that most people don’t know exists, is remembered only by high winds that overturn cargo trucks and blow off roofs, and by floodwaters that collapse dikes from their foundations and wash out roads. Paradoxically, only abnormal weather phenomena working literally to wipe the village from the face of the earth have not forgotten it.”

While some writers in the notebook witness climate change by looking to the past, some grapple with its realities by imagining the future. In a “Love Letter to the Eve of the End of the World, poet George Abraham refuses the colonial imagination and envisions the apocalypse as a beginning, “a new history / Of touch, not pitted against the land.” In reflecting on the poem, Abraham asks: “Is genuinely sustained and sustainable attention on climate change, and shared agency to work against climate change, possible without the dismantling of the western colonial world order?”

Elsewhere in the notebook, writers think about the generations to come. In Laurel Nakanishi’s “Another Sappy Love Poem About My Baby,” a parent imagines resilience and survival for their child. In a play on Maggie Smith’s “Good Bones,” Craig Santos Perez wrestles with passing on a ruined earth to the next generation. And in a reprint of his commencement address to the law school at the University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa, Julian Aguon urges community, collectivity, and persistence to make a better future. “Each of us who decides to engage in social change lawyering must find our own way to build an inner life against the possibility, and a certain measure of inevitability, of failure,” he says. “Indeed, part of our work as people who dare to believe we can save the world is to prepare our wills to withstand some losing, so that we may lose and still set out again, anyhow.”

We hope that you may find many points of setting-out in this collection of work—that these pieces may allow you to sustain attention to our changing climate and how it surfaces in our memory, our imagination, our present. And that to sustain attention might not mean to despair about the future, but to connect our shared histories and experiences so we might endure these changes and collectively take action to protect one another. We take inspiration from what Min Hyoung Song says in thinking about Shreela Ray’s “five virgins and the magnolia tree,” a poem in which the speaker wonders about the fate of the tree under which she once gathered with her friends on the cusp of adulthood. Song writes, “I believe we should behave as if there is still a chance to save the magnolia.”