“I want a literature that is not made from literature.”

I want a literature that is not made from literature. A girl walks home in the first minutes of a race riot, before it might even be called that — the sound of breaking glass as equidistant, as happening/coming from the street and from her home.

What loops the ivy-asphalt/glass-girl combinations? Abraded as it goes? (Friction.) (Concordance.) I think, too, of the curved, passing sound that has no fixed source. In a literature, what would happen to the girl? I write, instead, the tiniest increment of her failure to orient, to take another step. And understand. She is collapsing to her knees then to her side in a sovereign position.

Notes for Ban, 2012: a year of sacrifice and rupture, murderous roses blossoming in the gardens of immigrant families with money problems, citizens with a stash: and so on. Eat a petal and die. Die if you have to. See: end-date, serpent-gate. Hole. I myself swivel around and crouch at the slightest unexpected sound.

When she turned her face to the ivy, I saw a bunch or cube of foil propped between the vines. Posture made a circuit from the ivy to her face. The London street a tiny jungle: dark blue, slick and shimmering a bit, from the gold/brown tights she was wearing beneath her skirt. A girl stops walking and lies down on a street in the opening scene of a riot. Why? The fact of the riot decays around her prone form and at points it rains. In a novel that no one writes or thinks of writing, the rain falls in lines and dots upon her. In the loose genetics of what makes this street real, the freezing cold, vibrating weather sweeping through South-east England at 4 p.m. on an April afternoon is very painful. Sometimes there is a day and sometimes there is a day reduced to its symbolic elements: a cup of broken glass; the Queen’s portrait on a thin bronze coin; dosage; rain.

This is why a raindrop indents the concrete with atomic intensity. This is why the dark green, glossy leaves of the ivy are so green: multiple kinds of green: as night falls on the “skirt.” The outskirts of London: les banlieues.

I spend half my time staring at a mobile butcher’s block. The three wire cages are filled with notebooks and on the chopping board are the books I think will help me resolve the problems I am working on.

The sounds below the level of sounds that Ban makes: there. How pre-speech sounds are gamete-like: a kind of reproductive material that is simultaneously non-genetic and yet propagates: a future way of speaking.

Ban en Banlieues: suburban. A puff of diesel fumes on an orbital road. The country outside London, with its old parks and labyrinths of rhododendron or azalea, futile and tropical pinks in a near-constant downpour of green, black and silver rain.

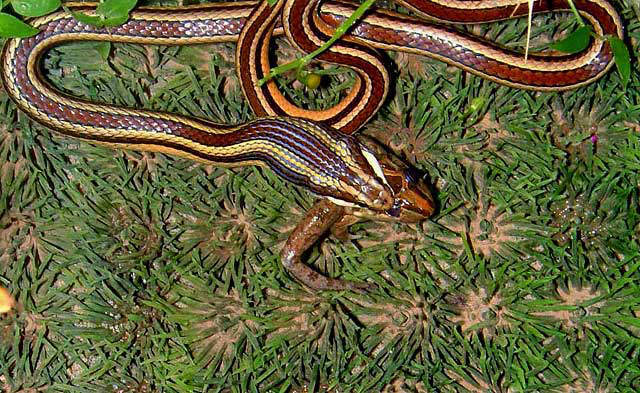

In the forest surrounding London, a light ice falls through the trees. The branches break the glitter. A snake, aspen-colored, bright yellow with green stripes, slips through the bracken, its pink eyes open and black diamond-shaped iris blinking on then off. In frozen time, ancient beings emerge with the force of reptiles. In the forest, time and weather are so mixed up, a trope of bedtime stories, bottom-up processing, need. I need the snake to stop the news. This is the news: a girl’s body is dressed and set, inert yet trembling, upon a rise in the forest. There are stars. Now it’s night. Time is coming on hard. The snake slips over her leg, her brown ankle. She’s wearing shoes, maroon patent leather shoes with a low heel and three slim buckles, but no socks. Whoever dressed her was in a hurry.

Imagine the scene: a forest outside of London, 10 p.m. An April snowfall, the bracken still coppery, gold. A snake has escaped from time: a suburban aquarium. Volatile, starving, it senses a parallel self, the girl’s body emitting its solar heat, absorbed in the course of a lifetime but now discharging, pushing off. Without thought, below thought, it moves towards her through the rusted trees.

Perhaps a street is a kind of balcony. The asphalt is filled with green stars, the shed parts of a ragged elm come Spring. Ban is a portal, a vortex, a curl: a mixture of clockwise and anti-clockwise movements in the sky above the street. I study the vapor as it rises, accumulates then starts to move. How a brisk wind organizes the soot or casings and bits of bark into whorls.

What is Ban?

Ban is a mixture of dog shit and bitumen (ash) scraped off the soles of running shoes: Puma, Reebok, Adidas.

Looping the city, Ban is a warp of smoke. To summarize, she is the parts of something re-mixed as air: integral, rigid air, circa 1972-1979. She’s a girl. A black girl in an era when, in solidarity, Caribbean and Asian Brits self-defined as black. A black (brown) girl encountered in the earliest hour of a race riot, or what will become one by nightfall.

April 23rd, 1979: by morning, anti-racism campaigner, Blair Peach, will be dead. It is, in this sense, a real day; though Ban is unreal. She’s both dead and never living: the part, that is, of life that is never given: an existence. What, for example, is born in England, but is never, not even on a cloudy day, English?

Under what conditions is a birth not recognized as a birth?

Answer: Ban.

And from Ban: “banlieues.” (The former hunting grounds of King Henry VIII. Earth-mounds. Oaks split into several parts by a late-century lightning storm.) These suburbs are, in places, leafy and industrial; the Nestle factory spools a milky, lilac effluent into the Grand Union canal that runs between Hayes and Southall. Ban is ten. Ban is nine. Ban is seven. Ban is a girl walking home from school just as a protest starts to escalate; the National Front have decided to hold their annual meeting in the council hall of a neighborhood with an almost entirely immigrant — Indian, Pakistani, Jamaican — population. Pausing at the corner of the Uxbridge Road, she hears something: the far-off sound of breaking glass. Is it coming from her home or is it coming from the street’s distant clamor? Faced with these two sources of a sound she instinctively links to violence, the potential of violent acts, Ban lies down. She folds to the ground. This is syntax.

Psychotic, fecal, neural, wild: the auto-sacrifice begins, endures the night: never stops: goes on.

As even more time passes, as the image or instinct to form this image desiccates, as Ban herself becomes a kind of particulate matter, I place tiny mirrors in the ivy behind her body. A cyclical and artificial light falls upon her in turn: pink, gold, amber then pink again. Do the mirrors deflect evil? Perhaps they protect her from a horde of boys in laced-up Doc Martens, or perhaps they illuminate — in strings of weak light — the part of the scene when these boys, finally, arrive.

The left hand covered in a light blue ash. The ash is analgesic, data, soot, though when it rains, Ban becomes leucine, a bulk, a network of dirty lines that channel starlight, presence, boots. Someone walks towards her, for example, then around her, then away.

I want to lie down in the place I am from, where this work is set: on the street I am from. In the rain. Next to the ivy. As I did, on the border of Pakistan and India: the two Punjabs. Nobody sees someone do this. I want to feel it in my body — the root cause.