This involves modulating my voice and accent so that I sound more Malay. It’s like having to work for my right to eat there.

October 30, 2019

Ta Pau // Bungkus: the bringing home of food prepared in a kopitiam or restaurant or cafe

The Ta Pau folio of the Transpacific Literary Project explores this cornerstone of Malaysian culture as a launching pad for honest conversations on national identity, race, religion, class, gender. Read here a collective philosophizing via email with Preeta Samarasan, Marion F. D’Cruz, and Su-Feh Lee, then take yourself back to folio’s home, for more Ta Pau conversation.

Preeta: I thought I’d get this ball rolling by talking about my earliest memory of ta pau-ed food. Which is this: when I was very small, my father used to bring home what we called “Chinese vegetarian food,” which was various kinds of Buddhist mock meat from a restaurant at a Chinese temple near our house. I remember the packages vividly, the outside newspaper layer, the sheet of cellophane inside, the different colours and textures of the mock meats. I LOVED that stuff, and ate it with such uncommon relish (I wasn’t much of an eater as a child) that my father, excited to have found something I would happily eat, began to bring home bigger and bigger bundles. All my favourite items would be saved just for me. My very favourite was a golden brown layered sort of thing, a little bit sticky and sweet, which, now that I think about it, must have been trying to simulate the skin of roast chicken or duck or goose?

What are your earliest/worst/best/most vivid memories of ta pau-ed meals?

And also—relatedly or separately—how would you translate “ta pau” into English in a way that reflects the Malaysian feeling and what it represents in our culture? Of course we have words like “takeaway” and “takeout,” but I wonder if there are more evocative possibilities. Like sometimes I hear people saying “pack home” or “bring home,” and that always strikes me as very different from “takeaway,” because the emphasis is not taking the food AWAY from the restaurant, but on where you’re going with it, where you’ll be when you eat it. It’s a shift of focus. What do you think?

Su-Feh: I cannot say this is my earliest memory, but it is the one that comes up when I think of a childhood memory of “ta pau”. Nor can I say that this is one memory; it is more a collection of remembered sensations. I am thinking of Hokkien Mee—thick chewy wheat noodles, slippery in a dark, unctuous, sauce made up of three ingredients without which it would not be Hokkien Mee: dark soy sauce (the Malaysian kind, not the Indonesian or elsewhere-Chinese kind), garlic and PORK LARD (in both liquid and crunchy form). And yes, the packages! In my memories, the newspapers could be of any language, but the plastic sheet that lined the newspaper—the “cellophane”, as you call it, Preeta—would always be pink. The time of day would always be night. Usually late at night—“supper” was the word we used to refer to the meal after the evening dinner. Was it for you too?

As for a translation of ta pau, I would say “pack home” is the most satisfying for me. There IS something about where the food is going, isn’t there? Also, to ta pau something in Malaysia seems more celebratory than to pick up some takeout in Vancouver. Why is that? Is that about “where” we are eating the food? About the quality of the takeout? Its specialness?

Marion: Not necessarily the earliest, but definitely a strong, recurring memory of ta pau food—when we were young, my brothers and I shared a room in a wooden house on concrete stilts—government quarters for government employees. We had one single bed for my eldest brother and bunk beds for my second brother and me. Often, late at night, my parents would come back from somewhere—visiting friends or some function—with supper for us. Yes…it was called ‘supper’, just like it was for you, Su Feh. This would most often be char kway teow and pau. Char siew pau and bak pau (the big ones). Bought from the stalls in downtown Johor Baru. The char kway teow was wrapped in a kind of leaf—light cream in color, tied with some natural product string—no newspaper, no plastic. We were regulars at these stalls and the owners/cooks knew us well. My parents would wake us up and although we’d be sleepy and sometimes grumpy, we would always get up and out of bed for this late night meal! Sometimes, as a family, when we were going home from an outing, we would stop at the stalls to buy supper to take home and eat. It was a regular feature in our lives.

We can still get very good char kway teow in Malaysia but good char siew pau is really hard to find. No more bamboo steamers…modern steamers…but no more delicious pau! These days, for delicious pau, one has to go to a good Dim Sum restaurant and pay high prices!

Ta pau—take home works best for me. When we eat out and there’s leftover food, we always say, “Do you want to take this home?” Then we ask the waitress to please pack or ta pau.

Preeta: Supper! Just the word awakens so many nebulous, ancient feelings in me. I think “supper” was something I lusted after a child, but there was a futility to that longing: supper was understood to be not for us. The possibility was never even discussed, though my mother often talked about other people going out for supper. The Chinese, of course, went for supper. Sometimes we would see our neighbours leaving the house as a family late at night, the children dressed in their pyjamas, and my mother would say “see how nice, they’re going for supper.” Now that I think about it, what she envied was probably the idyllic family scene rather than the supper itself. All those “close-knit” families, as my mother described them, laughing and talking and going out for supper.

Going out to eat for any meal was fraught for us: first, if we went to a Chinese restaurant (which was what we always wanted to do—we lived in Ipoh, after all, the vast majority of great places to eat were Chinese), we would be the only Indian family in the whole place. There was the staring to contend with, the whispering, most of it curious rather than hostile, but as a child I experienced this as exclusion, a feeling of being unwelcome in a space that belonged to other people. All in all, ta pau was the safest and happiest option for us. I think it’s largely thanks to the ta pau culture that we tried so many new and unusual foods, things my grandparents would never have eaten and that some of my uncles and aunts made fun of us for eating. We could ta pau these things and bring them back and sample them in the safety of our dining room, away from the curious eyes waiting to see how Indians would react to lor mee, or curry mee with blood cubes, or ham choy tong (yes, believe it or not, we would ta pau Chinese soups, despite the incredulous reactions of restaurant staff).

And now I’m wondering to what extent the entrenchment of ta pau culture in Malaysia owed itself—at least in the old days—to this need, conscious or not, to eat in your safe place, which must be more urgent in multicultural yet unequal societies like Malaysia. Outside the home, it’s a treacherous world, isn’t it? The rules are not always clear. In the 1950s, my grandmother’s sister sent her grandson out to buy two packets of mamak mee, giving him the instructions in Tamil: “rendu packet thulkan mee.” Now— “Thulkan” being the derogatory Tamil word for an Indian Muslim, on par with “keling” in offensiveness—any Tamil-speaking adult knows not to use that word, “thulkan,” in front of Indian-Muslims, but this was a little boy, and he didn’t know. He went to the mee man and repeated his order verbatim. “Rendu packet thulkan mee, saar.” The respectful addition of “saar” didn’t make any difference; the mee man chased this great uncle of mine all the way home, cleaver in hand.

What you were supposed to do was to bring the (thulkan) mee back home and eat it with your family, where your language would not endanger you. Where you could talk about the thulkan behind his back, just as (you assumed) he talked about you behind yours. What do you think of this theory? Is it pure nonsense or could there be something to it?

Su-Feh: Hmm. Ta pau as a way to eat in a safe space. I had never really thought of that but of course. As a Chinese body, I of course, am rarely uncomfortable in makan places in Malaysia because as you say, Preeta, Chinese people seem to have a big eat out culture. But of course, that’s because I go most often to Chinese coffeeshops and walk into those places with an entitlement unavailable to child Preeta. If I didn’t eat at Chinese coffeeshops, I would mostly eat at Banana Leaf places, or Indian-Muslim places. And the culture is familiar enough to me on account of my friends (you and you, for example) that I don’t feel Like I am walking into a hostile environment. I AM slightly uncomfortable in Malay eating places; because I feel the need to perform that I am not a Cina Babi, but a nice halus Cina person. This involves modulating my voice and accent so that I sound more Malay. It’s like having to work for my right to eat there.

A few years ago, after we threw my dad’s ashes into the ocean off Port Klang, we went to eat Nasi Dagang at a Kelantanese food stall. I felt so embarrassed to be walking in there with my large Chinese family, so loud and taking up so much space. I remember the look on my auntie’s face; she had no idea what Nasi Dagang was and was deeply uncomfortable at the stall. I secretly judged her for being insular and racist. But heck, she was probably afraid to eat in hostile places and didn’t know how to change her accent. I’m sure she would have preferred to ta pau.

Eating and socializing are part of our parasympathetic nervous system—the part that senses we are safe, among friends and so can take time to eat and digest, hear other human voices, see other humans and create bonds that will contribute to our collective safety, and personal well-being. Following this, your theory would make sense, Preeta. That we ta pau in order to eat in a safe space.

Marion: Interesting theory…yes, I suppose that home is a safe space for most things and should be a safe space for all things. So taking food home means that one can eat comfortably in that safe space. And I think it’s also about comfort…at home you can be in your pyjamas or in a sarong or you can be braless. Comfort at so many levels.

I eat out a lot, and have done so since the age of about 26. I eat in all kinds of restaurants—Malay, Chinese, Indian, Italian, Japanese, Thai—all that is available in Malaysia. And no, I do not feel uncomfortable or awkward in any. Sometimes however, if I go into a pub alone, I get stared at—older Indian woman with lots of grey hair, alone in a pub, is, I suppose, something to be stared at. How come we do not ta pau drinks? We do ta pau iced tea etc. But could I go into a pub and ask for a ta pau Margarita? Maybe if I took a flask, they would do it!!

I think the feeling ‘uncomfortable’ and getting stares and comments comes from quite a complex set of reasons. And I think some of it has got to do with class, skin colour, manner, dress, accent. And everyone falls into the trap of clichés and stereotyping. When I discuss racial stereotyping with my students, we often talk about how and why we respond differently to different people, and how it’s not just about skin colour. For example, if I were having a drink alone in a pub and a good-looking, well-dressed, white person with a matsalleh accent sits next to me and offers to buy me a drink, I might put on a fake ‘matsalleh’ accent and be quite chuffed. If a good-looking, well-dressed, very dark person did the same thing, I might think (or say) ‘Fuck off”. If a very good-looking, well-dressed, fair person with a very heavy Indian accent did the same, I might cringe. Whatever the reasons might be, similar rules seem to apply in many situations. In a Chinese restaurant, if someone enters who is very dark and in somewhat simple clothes, the stereotyping takes me to rubber tappers, poverty and coconut oil (although now of course Coconut Oil is a the miracle cure!!!). Maybe it’s about the fear of the ‘other’ which happens in all societies. What is the ‘dominant’ culture? What is generally accepted by all? That’s then the safe zone…the comfort zone. Anything that is out of sync with that, is to be ‘feared’.

There is a Chinese restaurant in Petaling Jaya called Sam You. They have several Indian waiters. Local Malaysian Indians. This is quite unusual. And Indians love going to that restaurant. Safety in numbers!

So what makes people ‘comfortable?’ Familiarity I suppose. In 1996, I did a collaboration project in Japan. There were 5 of us Malaysians—2 Chinese, one Eurasian and 2 Indians. We stayed in a small town outside of Tokyo called Shimoigusa. Everywhere we went, in this little town, people really stared at us. Not with hostility, but with curiosity. It was just so strange for nice Japanese folk to have these 5 ‘different’ people live in their community for 6 weeks! Preeta, I am sure you have many stories of your experiences in your French village. When are we ‘the other’ and when are we ‘not the other?’

Preeta: I struggle with this, with what Malaysians claim to be comfortable with and whether I should believe and respect these claims, because on the one hand I feel, well, y’all were saying that when I was a kid, and guess what, I DID NOT FEEL COMFORTABLE WITH IT EVEN BACK THEN BUT I WAS TOO SHY TO SAY. But on the other hand, I think these differences in comfort and discomfort and language and register are important to acknowledge—differences between societies, as well as individual preferences. If a person says “I don’t mind my friends calling me mamak,” who am I to question that and force my beliefs down their throat?

I’d love to go to Sam You one day! There was nowhere like that in Ipoh. But here’s the funny/sad thing: now I’m married to a white man, I can walk into any place with him with aplomb. “Status gone up already lah,” a Chinese friend of mine joked with me when he witnessed our entrance into a kopitiam one day—there are still stares, but it’s completely different—and we laughed and laughed because we all knew it was true. Sad, yes, but true. The ones who can laugh about this are the ones who question the stereotypes and the value placed on whiteness, of course; it’s often hopeless laughter, the laughter that follows rage, but what else to do? I do wonder if I’d have acquired this aplomb anyway without being married to a white person. I’m older now, I have more confidence, I care a little less about what people think, and I guess there must be something about me that has changed because people—taxi drivers, Grabcar drivers, random busybodies—often seem to assume, correctly, that I live overseas before I say anything. I don’t think it’s my accent because I don’t have one in Malaysia; I codeswitch like all of us do. I don’t know what it is, and I’m not sure I like it EXCEPT for this convenient fact that it allows me to waltz into many places I would have avoided before and not to care so much if the space “welcomes” me or not.

Ta pau Margarita, ta pau Negroni, now THERE’S a business idea to work on! In the plastic bag with the handles, and the straw sticking out. Wait, straw cannot, bad for the environment. But there must be a way. Ta pau cocktails are the future!

I wanted to come back to this idea of safe spaces and to point out that pork figures so prominently in so many of our ta pau meals. I mean, yes, it’s no surprise to any of us that food—which we so often celebrate as the thing that brings us all together as Malaysians—also segregates us by religion (and by race, since race and religion are intertwined in Malaysia). I’ve heard so many stories about how the old days were different, but nowadays, if a Malay/Muslim person wanted to eat from a non-halal shop—if, for example, they were comfortable ordering pork-free dishes from a restaurant that might serve pork —their safest bet would be to get someone to ta pau for them, to avoid being spotted by some jaga-tepi-kaining relative or neighbour. Of course I have many Muslim friends who wouldn’t go to such lengths, who would just sit down and eat wherever they want, but they know they are taking a risk; they’re willing to take it. There’s something to be said, maybe, about ta pau as an instrument of freedom. I want to share a story a friend told me; none of the people involved can be identified from this story, so I think it’s fine for me to share it.

An old friend of my friend’s, a Chindian man—this in itself is a funny detail, because of how Chindians are always getting mistaken for Malays, getting in trouble for not fasting or eating in non-halal places—was approached by his neighbour, a young Ustaz. The Ustaz said, “Eh, promise you won’t tell anybody, but I really, really want to taste pork, at least once. You can buy for me or not?” The Chindian neighbour was horrified at first, tried to refuse, but the Ustaz kept pestering. He said he didn’t believe in all these restrictive laws, that he believed his religion required him to think logically, and that thinking logically, there was no reason why he couldn’t try pork—but he said, of course, that this must never get out because other people wouldn’t understand, and he would lose his job. He needed his Ustaz job, it paid the bills. So finally the Chindian guy agrees. He goes, he ta paus some char siew and some siew yoke (I don’t know if perhaps he himself had to convince the seller that he wasn’t Malay, hahaha!), he brings it back to the Ustaz, who hides and eats it. Next day the Ustaz comes to him: “Damn sedap, man! Next time I want, you buy for me, okay?” And so the Chindian man became the Ustaz’s supplier. Could never have happened without ta pau, right?

Su-Feh: OMG that story is a KILLER!!!!! Everything Malaysia in there.

Marion: People maneuver their lives the way they need to. And there is so much policing that goes on—official and non-official. Many years ago, Krishen and I went into a Nasi Kandar shop in Penang, for lunch, during Ramadan. As soon as we sat down, the waiter asked us if we were Muslim. We said no. He was not really convinced. I showed him the cross I was wearing. It was all quite gentle. No hostility. I guess we could have been Indian Muslim and he was just doing his ‘job’ to make sure that he did not serve food to Muslims during the puasa hours. But it’s weird right? The idea of ‘sin’ and who decides who is ‘sinning.’

On the development of pork in Malaysia. In the ‘old’ days, there were halal restaurants and non-halal restaurants. There were seldom signs that declared their halal or non-halal status. Either people just knew, or they would ask before eating there, or they would still eat there and order only halal dishes. In the last 10 years, there are more restaurants that blatantly declare their non-halal status through the choice of names of the restaurant.

In KL we have:

Three Little Pigs & The Big Bad Wolf

S.Wine

Piggy Tail

Meat The Porkers (that has Siew Yoke Biryani)

There is also El Cerdo (which means The Pig in Spanish) The sign board of the restaurant says – El Cerdo – and the tagline is – nose to tail eating – with a drawing of a cute pig.

And these are just the ones I know of. I’m sure there are more. There are also many more restaurants that have ‘normal’ names but serve lots of amazing pork dishes. It seems to me that there is a rise of pork here in KL. I wonder why? Reaction to the rise of Islamisation? A tit-for-tat attitude? Or a sign that we are more liberal, more open, more sophisticated, more inclusive… It also means that these restaurants are quite happy to lose Muslim clientele. And it’s interesting that these restaurants got permission to name their restaurants such…or is that me exercising my own self-censorship? I actually find Piggy Tail quite bizarre…almost offensive.

Su-Feh: Some random thoughts:

While we want to eat in safety i.e. among friends and family, eating with people we don’t know will also build safety i.e. if I eat with you, there is a better chance I won’t kill you. So it’s always distressing to me when food culture excludes rather than includes.

These restaurants names seem to me partly political, partly entrepreneurial (cynical?) responses to the dominant culture or state-sponsored attempts to control what we eat.

When I was in Kuching, I was struck by how multi-cultural the clientele at the food courts were. Muslims, non-Muslims, indigenous, non-indigenous, Chinese, non-Chinese (but not many Indian people in Borneo) all sitting in the same space eating whatever they wanted in the same space. I want to believe in that dream or fantasy: that we can be different but together. That is the dream I thought I was working towards as a Malaysian. I am still working on that dream, despite countless heartbreaks.

I note that as we discuss ta pau, we are also discussing the opposite of ta pau, which is eating out. The private/public rituals and performance of eating. Eating is so intimate—you are opening your mouth and inviting something from outside of you to go inside of you. But while you are chewing, your insides—concretely and metaphorically—get seen in glimpses too. So one is vulnerable when one is eating. I never eat on the bus, and rarely eat on-the-go, shwarma dripping from my mouth while walking down the street, for example. I feel like I have been trained by living in Malaysia to always be mindful that something I am eating may be offensive or challenging for someone else: pork for Muslims, beef for Hindus. Meat for vegetarians. (Vegans, however, don’t really have as much of my sympathy.)

Preeta: Well, this, exactly this, Su-Feh, this vulnerability you point to as the reason you don’t eat on-the-go, is why I thought up this theory of ta pau being a protective measure in some cases and on some (perhaps usually unconscious) levels. In fact, I don’t always like eating in public. The less welcome I feel, the less I want to eat in public. The “weirder” my food is, too, the less I want to eat in public. (This is vestigial baggage from school recess time: you didn’t want to be the one with weird Indian food in your tupperware, or, perhaps even worse, Chinese-style food that wasn’t Chinese enough, that was incorrectly made. I wanted to buy the canteen food but I didn’t always have pocket money, so I simply stopped eating at school.) And ta pau is a way around that, isn’t it? There’s also the feeling of wild abandon when you can eat alone and in private (or is that just me?!?)—who cares if you’re dribbling sauce down your chin, who cares if you’re making unattractive sucking sounds while eating your chili crabs, who cares if your cheeks bulge terribly when you put a whole dumpling in your mouth!

I’m inclined to believe that some of this desire for privacy must happen, some of the time, for Muslims who want to practice their faith selectively, or for ex-Muslims. But then, I’m Facebook friends with a fair number of Malaysian ex-Muslims, and many of them like to post pictures of their porky meals on Facebook. I guess that’s the *opposite* of the safe space, again, eating pork in public. I joked with them that this was “porktivism.” A way to make the point that a human being should be free to do as they want as long as they are doing no harm to others. Really, if it was *just* about the pleasure of pork, the flavour of it, they would ta pau, right, like the Ustaz in my story?

Su-Feh: Is there any other place in the world where pork is as politicized as it is in Malaysia?

Marion: I ate a lot of delicious bacon while in London—either in a restaurant or pub, or at home. The only time we did a ‘take-away’ was fish and chips which we ordered online and it was delivered. The quality of bacon in London is superb. I also cooked Pork Veenyali (Vindaloo-vinegar curry) for my niece Jessica and her boyfriend Liam. Interestingly, they love this very Malayalee dish which is actually quite strong in flavour. I also made corned beef cutlets. A lot centres around food during my visits there and vice versa. When Jessica visits, we make a list of all her favourite food and tick them off the list, as she gets to eat them. Mutton varuvel features very high on this list.

There is so much about food…that brings us together and separates us as well. Eating together is surely one of the most joyous things. All the rituals around food. In the ‘old’ days, at any time of the day, when someone visited, the standard question was, “Have you eaten?” Hours and hours around the dining table—eating, talking, laughing, drinking tea. In the 1980s my house in Medan Damansara was like ‘Grand Central Station’. People came in and out. Stayed for hours. Talking. Eating. Drinking. Sharing our lives. No one asked whether they could visit. They just popped in. And stayed. Su-Feh—you discovered your love for Barfi. Nowadays, I really do not want people to just pop in. I want people to let me know that they would like to visit. That’s quite sad actually.

Su-Feh: My love of Barfi is inextricably related to my love of you and Krishen and the sense of having found a safe place in my life at a time when not much felt safe to me.

All those sensations are there every time I ta pau barfi from a restaurant in Vancouver.

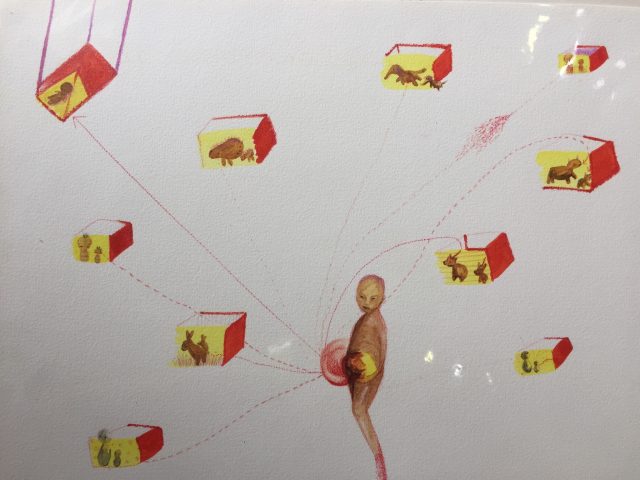

It’s like my body is the ta pau package for memories associated with the ta pau food.

Marion: This conversation has affected me quite a bit. Every time I go to the cafe in Aswara, I notice when people are ta pau-ing food instead of eating in the cafe. I notice who is doing it, I wonder why they are ta pau-ing instead of just eating in the cafe. Our cafe is not great. It’s sometimes dirty and there are lots of cats. They are very obnoxious cats who jump on to the tables as you are eating. The students love the cats and feed them and hence these cats are brave and obnoxious. I am ok with cats but not when they jump on the table. I very rarely ta-pau food from the cafe to eat in my office. When I do eat from the cafe, I prefer to sit and eat there…..cats and all. I enjoy the break from my office. I don’t want to eat in my office. Most of my colleagues prefer to ta pau and eat in their offices. Cleaner. More comfortable. Safer??

I have also begun to notice more carefully when I ta pau food from anywhere else. I notice others and I notice my own self. I had a meeting on Tuesday at a cafe called For Goodness Cakes! The quiche and salad that I ate was delicious and the lemon drizzle cake was heavenly. So I decided to ta pau some cakes for my colleagues at Aswara. I realised that ‘ta pau’ was not the correct word for packing cakes in little cardboard boxes. One slice lemon drizzle cake, one slice ginger cake, one red velvet, one sticky date, one almond sugee, one carrot walnut. 6 cakes. Packed in 3 boxes. Packed. In my head, ta pau was just the wrong word for these cakes. I asked the lady to please pack some cakes for me. I did not ask her to ta pau. WHAT DOES THIS MEAN? Ta pau is only for local food? Can you ta pau a pizza or some pasta? Can you ta pau curry puffs?

Su-Feh: Ta pau cannot be in boxes in my opinion. It must be in cellophane and newspaper. Or you must be able to imagine the food in cellophane and newspaper. So nonya kuih can ta pau. But cupcakes, cannot.

Marion: Which means there is hardly any more ta pau in KL. Everything is in boxes or plastic containers or styrofoam containers. Except goreng pisang from a stall. Even that is usually just put into a plastic bag. Maybe it’s deeply symbolic. Maybe there are really no safe spaces anymore.

Preeta: So this distinction between “ta pau” and other food we take home but don’t call “ta pau” is SO interesting to me! Now I’m wondering why I’d never thought about this before, but yes, of course pizza is not ta pau. Yet our own Malaysian “Western food” is prime ta pau territory: you can ta pau a Hainanese chicken chop or pork chop, but you can’t ta pau a pork chop from one of those high-end pig-titled places in Bangsar, can you, even if they let you take it home with you? You can still call it ta pau if it’s in one of those (terrible) styrofoam clamshells, right? Is that because we can *imagine* it in cellophane and newspaper, like you said, Su-Feh, or is that because—scary thought—we have embraced styrofoam as a Malaysian cultural artifact? Has styrofoam become as Malaysian as banana leaves and newspaper and cellphone? I remember getting styrofoam clamshells of chap fun as far back as the mid 1980s, from a chap fun place a few doors down from my school on Brewster Road, Ipoh.

My parents have a wonderful neighbour who is always giving them homemade food. One time, she made a pandan chiffon cake and gave them slices in one of those styrofoam clamshells. I was really confused by that—how come she didn’t just put it on a plate to hand over the fence?!? Did the clamshell somehow lend it more prestige, in her mind? I was reminded of that Pang Khee Teik quote that went viral, about how Malaysian Chinese will say, “Wah, so good, like homecook!” when a restaurant meal is exquisite, and, “Wah, so good, can open restaurant oreddi!” when a homecooked meal is perfect. (I might be paraphrasing here, but that was the gist.)

Marion: So here’s the thing…ta pau is HOME. Something HOME about it. Something nostalgic but also current. Something from memory but also now. Something warm and nice and easy and yes…something safe. To just pack food is functional. Ta pau has more than just function attached to it.

There’s a shop in KL called Naiise where they sell just wonderful ‘Malaysiana’ stuff. Cushions in the shape of a jam tart, curry puff, gem biscuit, etc. Door stoppers that look like kuih lapis, etc. It’s a wonderful shop. They have a container which is rectangularish with a handle….a sort of cup but it’s for when you ta pau a drink in a plastic bag and need a container. So you put the plastic bag of drink in this container and it holds it perfectly. That way, if it’s a cold drink, the condensation from the bag will not drop on you. If it’s a hot drink, it’s definitely easier to hold it in a container. It’s a very clever idea…or is it? Of course, one could just put one’s ta pau drink in its plastic bag, in any other glass or container. One needs to carry the said container when buying a ta pau drink. If one has to take the container, then one could easily just buy the drink in the container! But…it’s very cute to see the ta pau drink in the said container.

Preeta: I share your questions about whether one needs to gild the lily in this way. If we’re thinking about the environment (and we all should be!) then the oldest methods of ta pau are the best: banana leaves, tiffin carriers. My parents have already gone back to tiffin carriers; at first they thought stall owners in their neighbourhood (they live in Cheras, so all the vendors are Chinese, of course) would be annoyed, but no, no one has batted an eyelid. The dimsum man happily packs their siu mai and har gow in their stacked tiffins; the wantan mee lady puts the mee in one tiffin and the soup in another. Yong tau foo, chee cheong fun, everything goes in the tiffins now. We should all be doing this. The mountains of rubbish from our ta pau habit are scary. KL’s largest pasar malam—the Taman Connaught one—happens steps from my parents’ house and the streets are in an atrocious state the morning after because *everything* is ta pau-ed, even by people who eat it right there or while walking around the pasar malam. Plastic cups, straws, endless styrofoam and clear plastic clamshells, plastic cutlery, mountains of it every week. Imagine if there were two choices: either you come with your own container, or you stand there and eat, the way we used to eat lok lok in the old days outside the school gates or the cinema, sharing the dipping sauce with the crowds…

Marion: It’s beginning to change these days. People are beginning to take their own containers to ta pau food.

Su-Feh: I have started carrying empty containers in my backpack. Water bottle, coffee cup, tupperware (not actually Tupperware from a Tupperware party, remember those?, but generic plastic container) along with my dance and workout clothes AND my computer. I feel like my entire life is a ta pau.