The author of The Collected Schizophrenias speaks to the challenge of telling truths when writing about a disorder that lies over and over again

March 4, 2019

I met Esmé Weijun Wang a handful of years ago at the AWP conference. Under the pale strip-lights, she was looking a little overwhelmed but her bleached pixie cut and red lipstick were immaculate. She spoke slowly, taking her time to think between words. Her voice was slightly husky. I can’t remember what I said. I suspect that I was trying both to convey and to hide how much and how long I had loved her words. Convey, because I hoped it would give her joy. And hide, because I suppose love is always a little embarrassing.

I never really understood those people who go to lengths to tell you they liked a band when it was starting out, or a singer before she got famous. It always seemed an absurd bid for ownership. Why does it matter that you liked someone early? You were just lucky.

Then I realized that I’m always telling people that I was reading Esmé Weijun Wang before her first book. I stumbled on her blog as a confused, lost teenager. There was something about the urgency, thoughtfulness, and rawness of those early entries that made me feel safe. Here was this person who struggled with mental illness and who loved aesthetics and fiction. I kept following her writing. When I bought her novel The Border of Paradise, it was everything I hoped for. The book is about incest, love, foreignness, family, suicide, and yet, somehow, it’s also really quite funny.

Then I realized that I’m always telling people that I was reading Esmé Weijun Wang before her first book. I stumbled on her blog as a confused, lost teenager. There was something about the urgency, thoughtfulness, and rawness of those early entries that made me feel safe. Here was this person who struggled with mental illness and who loved aesthetics and fiction. I kept following her writing. When I bought her novel The Border of Paradise, it was everything I hoped for. The book is about incest, love, foreignness, family, suicide, and yet, somehow, it’s also really quite funny.

Later, I asked Esmé to write a piece for the Go Home! anthology I was editing. She obliged with an essay about food and sickness. Readers told me how much they’d loved it. I replied—I know. I know. And it came to me that the people who talk about bands this way aren’t trying to own the singer. They’re trying to say that fame aside, something about this person sends a cord thrumming deep within them. They are trying to say that the fame is irrelevant, that if you listen to this person, you will know something important about me and what I love in this world. But part of being a gracious fan is acknowledging that the person you love may set the same chord thrumming in thousands of people, and there is joy to be found in that too. So, when AAWW asked me to write something about her new book, I emailed her publisher for a copy as fast as I could.

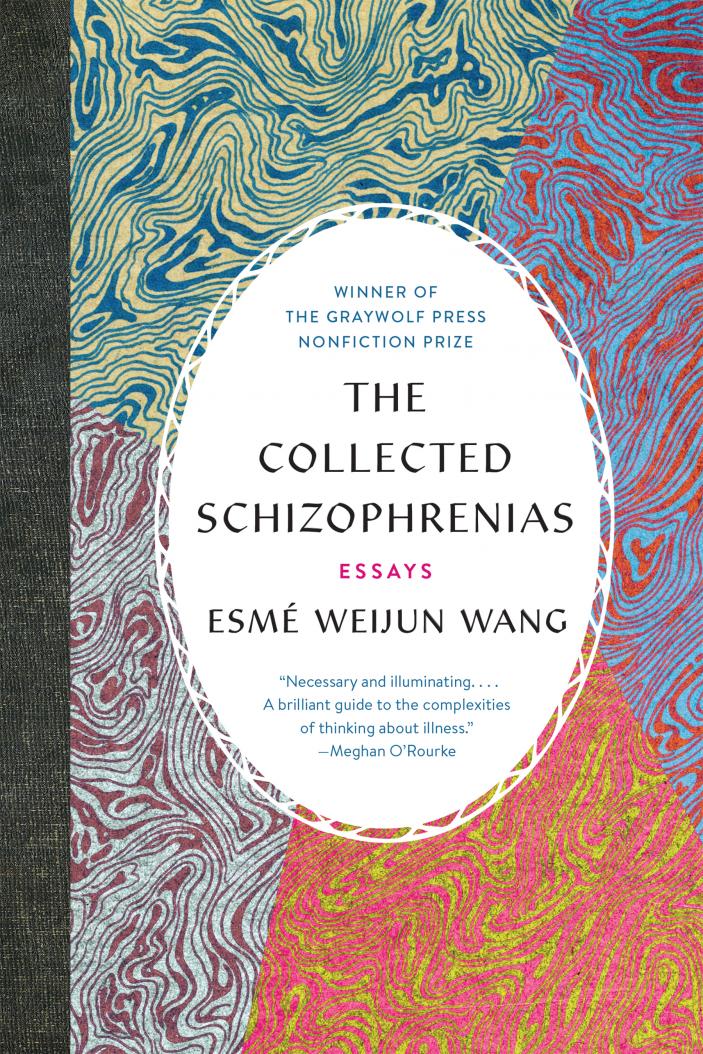

The Collected Schizophrenias takes all of the vulnerability of her early blogging and combines it with a serious inquiry into the history of schizophrenia. This book is about Esmé, but it is also about sickness more broadly. The essays follow her journey from diagnosis, through dropping out of Yale and the processing of abuse, to life as an ambitious adult living with the disorder. Using herself as the lens, she explores the history of the disorder, disagreements within the medical community, the failure of educational institutions to appropriately accommodate mental health needs, the effects of stigma, and whether the delusions of schizophrenia might have meanings not at first apparent. Throughout, her authorial voice is gentle, even conversational. It is a voice that you’d trust to walk you through hell.

I wrote to Esmé to ask her a few questions about how this book came to be.

—Rowan Hisayo Buchanan

Rowan Hisayo Buchanan: You’ve shared quite a lot on your blog. But your book goes to darker and more vulnerable places. Do you think the change of medium affected what you felt able to say?

Esmé Weijun Wang: Writing in my blog and writing in this book felt vastly different—I’d been blogging on and off for years after I shuttered my LiveJournal, but what I wrote there was never meant to be seen by a larger audience other than the few thousand who happened across it. It might then seem odd that this book, which is being actively publicized, would be more vulnerable than that blog; still, the book was intended to be literary, whereas the blog, which was always a casual medium for me, wasn’t. The challenge of writing about the schizophrenias in a literary medium inspired me to pull from all kinds of places, and to work a good deal harder.

That’s fascinating. I’m not sure everyone associates vulnerability and work as being intertwined but I think that hits at a truth. Personally, when my writing becomes vulnerable, that is when I have to push myself most as a writer. I feel such urgency to shape it exactly right and not to be misunderstood.

Can I ask you to elaborate a little more on how that feels for you? Is it more work because of the desire to explain these things exactly correctly? Because of the detailed research you have clearly done? Or the feeling of pulling it out of yourself?

Yes, I think that second line you said gets at it—I want to explain these things as correctly as possible in my books, and in my published essays. My blog feels sloppier, like a journal or a diary; I’m able to be messier. I rarely research for my blog, for example. I want to be as precise as possible when I’m writing for a larger audience, particularly when I’m being vulnerable as well, because of a responsibility I feel to tell the truth.

In both your blog and your book you describe yourself as an ambitious person. Do you think knowing you have an illness makes you more ambitious? Does it give you more reason to prove yourself?

I don’t think that having various illnesses makes me more ambitious, but I do think that it makes me more aware of the ambitions that I already have. My online business is called The Unexpected Shape, which refers to the limitations, or boundaries, that so many of us ambitious people encounter at some point in life, or are born with; it wasn’t until I got really sick, and found myself frequently unable to do things that I’d previously found simple (such as staying awake past 5 pm, or being able to sit at a desk for half an hour or more) that I found the unexpected shape of my ambitions. I wanted to write books; I wanted to build a successful business; I wanted to have vibrant friendships and a loving, stable marriage. Finding it more difficult to pursue these goals means that I have to actively find workarounds if I want to keep after them.

Would you mind giving an example of such a work around? I think it might help or inspire readers who are struggling with similar issues.

The workaround that I talk about the most is working on my phone, or working on my iPad mini, instead of working on a laptop. I’m answering these questions, for example, on my phone. I wrote most of my essays on a phone or an iPad mini because it’s hard for me to work on a desk, or to sit upright for long periods of time; because it’s easier for me to work when lying down on my side, I tend to work by tapping on a small screen.

One of the things that seems to be the biggest challenge for you in these essays is managing the perceptions of those around you. I was particularly moved by your description of dressing to inspire respect. Is there a path you see between treating people with mental illness as monsters defined only by sickness and treating mental illness as unreal, as in the case of the graduate student instructor who says he won’t give accommodations to students with depression because “it was easy enough to pretend to be depressed”?

It’s all on a spectrum of sorts, it seems—you mentioned not being believed, or in another instance, being believed to the point where the disorder becomes your identity. With mental health issues, neither is ideal. At the same time, the schizophrenias in particular are currently stigmatized to the point where I can’t imagine a professor accusing a student of pretending to have a schizophrenia diagnosis, because who would opt to take on that label? So those diagnoses become particularly fraught.

When you describe being hospitalized you write, “We cannot be trusted about anything, including our own experiences.” You are writing of how the institution treated you but I wondered if this was a fear you had about readers as well? When you are repeatedly told not to trust your own brain and have experienced delusions, does that affect how you approach writing about your experience? Do you feel able to trust your memories?

I worry about how the reader will interpret me, yes. I can’t worry too much about it, because the premise of the book is that I’m presenting a form of truth, or at least, my truth. The book has been fact-checked and I’ve gone through my journals to verify various things, and it’s as close to the truth as I could make it; because the book is about the schizophrenias, it’s built on a disorder that lies over and over again, but I’ve also been fortunate enough to grab hold of what’s called, in psychiatric terms, insight.

You use the word “insight” again and again in the essays. Early on you are told you don’t have it, and later you do. Later still, you talk to your friend about the possible insights (non-medical) that your illness might be trying to give you. Would you mind describing the similarity/difference between psychiatric insight and the day to day kind? Do you think there is a link between the two? Do you believe it is possible to have one and not the other?

Psychiatric insight is when a person with mental illness is aware that they have a mental illness. The standard kind of insight is to be aware of a wide variety of things, which may or may not have to do with mental illness; it’s possible to have one and not the other, and vice versa. You could understand that you have OCD but not understand that your actions are racist, for example. Humans are capable of all kinds of insight; simultaneously, humans are capable of all kinds of ignorance.

More generally, as an artist and a thinker, how do you manage when so much of living with mental illness is learning to distrust many of your first instincts? I ask this one partially because, as someone who has struggled with severe depression, I ask myself this question a lot.

It’s really difficult. In the worst times, I end up doing a lot of reality checking—my primary diagnosis is schizoaffective disorder, bipolar type, so I’ve also experienced severe depression and mania. Psychosis, mania, depression, anxiety, dissociation, panic, etc. are all tremendously good at lying to me, and a lot of my time is spent doubling back and realizing that I’ve been going down a road that might not be completely true.

From your drawing and your photography, it is clear that you’re a very visual person. You write about how you used photography to ground yourself during times of sickness. I wondered if there were any photographs that speak to your work in this book that you’d be comfortable sharing? I thought a nice way to end this interview would be to see the world for a moment through your eyes.

Here’s one:

This was taken during the winter when the Cortard’s delusion that I write about in “Perdition Days” was taking place. It was a literally hellish time; I thought I was dead and in hell, and the air was crisp and cold. When I see this photo, I remember the way the air felt, and the way the light seemed so clean. I remember seeing the Be Brave decal on my office wall every day and how it seemed to be a message from another time, and from so far away.