“The process of writing a novel can sound cohesive and tidy. At the time it feels much more like walking around in a very dark and very cluttered room, moving slowly, hoping you’ll run into something like an intention instead of a sharp object, or more often, a wall.”

January 16, 2020

“It is a small face, with small, plain features, so plain, in fact, that the face resembles a blank paper, on which anything can be drawn.”

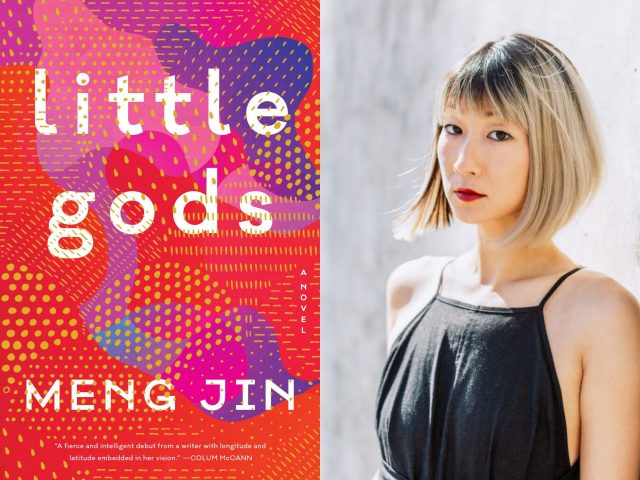

This is how we meet Su Lan—a talented, young physicist on the cusp of a career break involving the nature of time, and the character at the center of Meng Jin’s novel Little Gods. The observation is made by a nurse on duty at the maternity ward in Beijing where Su Lan arrives the morning of June 4, 1989 with her husband to give birth. By the end of her labor the pro-democracy movement in Tiananmen Square has failed and Su Lan is left to raise Liya, her newborn daughter, without a husband. The novel attempts to trace Su Lan’s decisions for the next seventeen years and the effect that isolation and self-abnegation has on her only child.

As the novel opens we learn that Su Lan has passed, leaving her teenage daughter in the States to piece together her past. While searching for traces of her mother’s history in Shanghai and Beijing, Liya describes a physics principle whereby certain objects “assure us of their existence simply by the way they affect the behavior of nearby lesser objects.” As a scientific theorem, it’s a tidy explanation for the existence of black holes and other measures of gravity that warp time and space, and as a metaphor, it describes the magnetic hold that Su Lan continues to exert over her loved ones long after her death.

At the heart of Su Lan’s story is a love triangle between childhood friends and the extremes that one woman goes to in hopes of transcending her impoverished beginnings. Su Lan’s world is one in which circumstance—being born in a city versus the provinces, attending school in Beijing versus Shanghai, fighting for communism or for the pro-democracy movement—can determine the course of an entire life. She yearns to escape the past, to grow up as a woman with “no history,” but her erasure creates a rootlessness in Liya that disrupts the life of every character and helps determine the course of the novel. Like Liya, we begin to question her mother’s choices. Is Su Lan cruel? Selfish? Or shrewd and determined?

In Little Gods, Su Lan never speaks directly to the reader. Instead, it’s her neighbors and family members who have the chance to reveal facets of her personality at different points in time. Like Einstein’s theory of relativity, our view of her character shifts along with the position of the speaker. The novel is a complex portrait of an ambitious woman circumscribed by events both within and outside of her control. Little Gods promises that while the decisions we make may appear to be self-determining, we have no choice but to eventually encounter another version of ourselves, including the ones we’ve left behind.

—Jen Lue

◻︎◻︎◻︎

Jen Lue: I remember hearing you read an early version of Little Gods at an MFA program graduation years ago. How did the novel evolve, from then until now?

Meng Jin: The short answer is: a lot. If I’m remembering correctly, the excerpt I read at my MFA graduation is no longer in the book—not a single word of it. I started writing this book before I knew how to write at all, before I had a clear sense of who I even wanted to be as a writer. I had many false starts and discarded drafts. Each time I reached the end, I felt like the draft had turned me into a different writer than the one who started. I would begin again with a blank document as the new writer I’d just become.

JL: How did you know when it was finished?

MJ: In the early drafts, and all through my MFA, I wrote with the feeling of “Is this working? Could this work? Maybe? Maybe!” I knew I was near a final draft when the answer was, “Yes, this is what I wanted to say.” By the time I was done with the book, I had evolved from a writer who tinkers endlessly to one who starts every revision from scratch, with an almost superstitious belief that a work can only be compelling if it comes from me propulsively, so that as I’m writing I feel as if I’m racing, trying to catch the story as it runs ahead.

JL: The chapters narrated by Yongzong, Liya’s father and Zhu Wen, Su Lan’s former neighbor, are addressed directly to Liya. The reader has the feeling that she is eavesdropping on a privately-told origin story. How did you come up with this structure for the book?

MJ: I always knew that the novel would be told indirectly, with an absent protagonist (Su Lan) as the magnetic center. Early on I had a vision of a black hole, with objects orbiting around it, falling into it. I think I was drawn to this kind of structure because it formally echoed the story I wanted to tell—a story in which the absence created by a loss (whether it be death, immigration, or willful obliteration of one’s past) becomes so powerful it creates its own mythology.

The slant narration that resulted—three first-person narrators telling a story about someone else—was deeply appealing to me for many reasons. From a technical perspective, it allowed the freedom of third-person narration with the intimacy and organic unfolding of a first-person confession—that feeling of eavesdropping that you mention. And it created a natural complexity in the narration: what is told is always qualified by how it is told. From a thematic perspective, this structure allowed me to explore the ways in which we are known and unknown to others and to ourselves.

In early drafts of the novel, the three narrators’ sections were whole and separate. The book was like three novellas framed by opening and closing bits. While this was structurally pleasing to me in many ways—it asked the reader to do more work in bringing the sections together—my agent worried that the structure would not be cohesive or clear enough. I had worked with my agent for a while by then and had learned to trust her instincts. So I tried splitting the sections, and that was when I added the direct address to Liya in Zhu Wen’s and Yongzong’s parts. I knew I had made the right change because this tiny structural shift solved other totally unrelated problems in the most elegant and simple way, and the story seemed to just fall into place.

JL: Su Lan is equally described by others as “plain,” “nothing particularly extraordinary” and so beautiful that she “erased the need for history.” Why such varying descriptions of her physical beauty?

MJ: What an interesting observation. If I’m remembering correctly, all three of these descriptions are from Yongzong, but at different points in his story, right?

In Yongzong’s section in particular, Su Lan is more of the narrator’s projection of himself than a reflection of who she actually is. Yongzong describes Su Lan as plain and unmemorable, even ugly, when she is a nobody. Later, after her status has risen and rumors about her beauty abound, he sees her as beautiful too. The last, rather dramatic description comes at a time when Yongzong has projected so much meaning onto the object of his desire that he can no longer see anything but his own desire.

Perhaps I wanted to show how what we perceive as beautiful, especially with regards to women, is so changeable that it says very little about any absolute or objective measure of “beauty” and more about our own vision; it is our own desire, inflected and informed by cultural forces, that creates the beauty we see and the beauty we are blind to.

Beauty can also be power: Su Lan understands this instinctively. She transforms herself into a beautiful woman in the eyes of those who might judge her. She understands that in her time and place, beauty is one of the few forms of power she can access, so she uses that power as a tool for class mobility.

JL: Su Lan and her classmate, Zhang Bo, grow up poor in the provinces while Yongzong, her husband, is born and raised in Hangzhou, as the son of an educated man. In one passage, Su Lan describes Yongzong as having “never questioned his ability to succeed, and this makes him easy to hate.” Why was it important to emphasize the class differences between characters and how class is intricately linked to region?

MJ: I always thought about this novel as dealing with migrations through time, space, and class. I wanted to explore the cognitive and emotional dissonance experienced by people who undergo these extreme migrations. How does one cohere a sense of self if everything about her life circumstances has changed, perhaps even turned upside down? Movement through time and space are obvious sources of change, especially in an immigration story. But movement through class can have an equally dramatic effect on a person’s psyche. We think of the measure of a successful society as one in which class mobility is possible, and yet the deep psychological impact of moving through class, in individuals and in communities, is rarely as explicitly acknowledged. For a story set largely in contemporary China, which in the last thirty years has experienced economic change at a hallucinatory pace, it felt natural, even necessary, to articulate these differences in class.

JL: It’s interesting to see Liya take on some of Su Lan’s characteristics during her journey from the States to Shanghai and Beijing. While searching for her biological father, she forms elaborate lies about her family background and finds herself treating Zhu Wen and her mother’s former lover dismissively while extracting information from them. Was it your intention to show how mother and daughter were linked in this way?

MJ: Hmm, I don’t know! It’s hard to know one’s intentions in writing, though I realize that in the answering of these questions it must sound like I had a lot of intentions. Retrospectively, the process of writing a novel can sound casual and cohesive and tidy. At the time it feels much more like walking around in a very dark and very cluttered room, moving slowly, hoping you’ll run into something like an intention instead of a sharp object, or more often, a wall. To answer your question, I think I actually intended (as much as I intended at all) for Liya to reveal herself as more like her father than her mother. In my mind she had inherited his ability to lie, to be ruthless, to translate himself—traits her mother desired but was unable to fully possess. But what do I know? Your interpretation is as good as mine. Probably better, since you’re unbiased by my intentions.

JL: There seems to be a dichotomy between characters like Zhu Wen and Su Lan, pragmatists who are committed to a “reality dictated by logic and fact,” and the passions of Su Lan’s husband, Yongzong and other political actors ranging from the Cultural Revolution to the pro-democracy movement. What does this say about Su Lan’s character and her relationship to nationhood and national identity?

MJ: In some ways the difference is simply one of temperament. Su Lan is interested in things both smaller and larger than national politics, in scales of time much shorter and longer than the ones in which political movements have an effect. That’s simply how her mind works. Both she and Zhu Wen are loners by nature, distrustful of large groups because they have never felt welcome in such contexts. They are the type of people who might feel uncomfortable in a protest, plagued perhaps by a sense of bad faith that turns easily into resentment or a desire to disengage. Yongzong, on the other hand, is extraordinarily energized by the feeling of collective effervescence, partly because he has never doubted his belonging in the center of a group.

In the language of activism, I could also say that Su Lan and Zhu Wen are people who see themselves as existing outside of the political system. They don’t buy into a strong sense of national identity, they don’t become invested in ideas of change or revolution, because they don’t really believe that any changes will affect them at the end of the day. They are so disenfranchised, and feel so powerless, that apathy seems the safest route.

JL: Reflections and mirrors play an important role in the book. In Shanghai, Liya picks up a photograph of her mother in her old apartment, “holding it like a mirror.” In a fight with Yongzong early on in their relationship, Su Lan accuses him of “want[ing] a mirror, not a woman.” How do mirrors and identification navigate the relationship between self and other?

MJ: I think this may be another one of those instances when the reader is smarter than the author. While I was writing, I didn’t think consciously about any of this. Rather, one of the major questions that needled me in the writing of this book was that of self-recognition. Someone like Yongzong, who is so obsessed with status and how he is perceived by others, walks through the world constantly looking for a mirror. He would rather see a reflection of himself than confront an other for who they truly are, or worse: himself as he truly is. For Yongzong the mirror is a kind of veil. (Can you tell I’m not a fan of this character?).

For people like Su Lan and Liya, however, who continually find themselves pushed into new contexts—often contexts in which they exist in the margins—or for someone like Zhu Wen, who doesn’t see a place in the world for someone like her, the task of self-recognition can feel especially urgent and fraught. Standing before a mirror, each is forced to recognize herself, whether she likes the image reflected back or not.